Visual Abstract

Luspatercept has emerged as a novel therapy for anemia in transfusion-dependent (TD) lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (LR-MDS). This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in TD LR-MDS. Six databases were searched through March 2025 to find relevant material. Studies were screened and extracted by 2 independent authors. A total of 20 studies encompassing 3455 patients were included in the analysis. The pooled 8-week transfusion independence (TI) rate was 51.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 39.9-60.4; I2 = 94.9%), with higher rates observed among ring sideroblast–positive (RS+) patients (57.8%; 95% CI, 47.4-67.7; I2 = 86%) and those with low transfusion burden (LTB; 72.9%; 95% CI, 60.4-82.6; I2 = 0%). The 12-week and 24-week TI rates were 57.0% (95% CI, 48.1-65.5; I2 = 90%) and 35.8% (95% CI, 28.7-43.6; I2 = 82.1%), respectively. Hematologic improvement–erythroid was achieved in 51.3% of patients (95% CI, 41.3%–61.2%; I2 = 93%). The most frequent adverse events were peripheral edema (17.8%; 95% CI, 11.4-26.8), diarrhea (15.6%; 95% CI, 8.2-27.7), and fatigue (11.4%; 95% CI, 5.4-22.6). Serious adverse events occurred in 28.0% of patients (95% CI, 12.8-50.7; I2 = 97.2%). Luspatercept is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for anemia in TD LR-MDS, especially in patients with RS+ and LTB. Its favorable safety profile and high TI rates, particularly in erythropoiesis-stimulating agent–naïve populations, support its use in the frontline setting.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms (MDS) are acquired bone marrow disorders characterized by insufficient hematopoiesis, with an incidence of ∼4.9 new cases per 100 000 individuals in the United States.1-3 Anemia is the most prevalent manifestation of lower-risk MDS (LR-MDS), with many patients becoming red blood cell transfusion dependent (RBC-TD) and needing regular blood transfusions.4,5 Long-term receipt of RBC transfusions leads to transfusion-associated iron overload with ensuing end organ complications, diminished quality of life (QOL), and ultimately reduced overall survival.6-8 Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) have been widely used to reduce transfusion burden among patients with MDS; however, most patients either fail to respond or relapse after an initial period of effectiveness.9-11 Luspatercept, a novel transforming growth factor β superfamily ligand trap and first-in-class erythroid maturation agent, has emerged as a novel treatment for anemia in LR-MDS that has garnered regulatory approval in both the United States and Europe.12,13 Luspatercept demonstrated greater efficacy than ESAs in achieving RBC transfusion independence (RBC-TI) among patients with MDS who have anemia, especially in the presence of a SF3B1 mutation or ring sideroblasts (RSs).13-16 However, data for patients without SF3B1 mutations or RS are more mixed, and several additional real-world studies, in addition to the landmark MEDALIST and COMMANDS trials, have been reported.13,16 To comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in LR-MDS, we performed, to our knowledge, the first systematic review and meta-analysis of luspatercept for the treatment of anemia in LR-MDS.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the recommendation of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis), and the study protocol was published on PROSPERO (CRD42024574093) before conducting the study.17,18 PRISMA checklists are available in the supplemental Materials.

Search strategy

We searched Cochrane Library, Ovid Embase, Google Scholar, Ovid MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection to find relevant studies from database inception to 29 March 2025. A combination of Medical Subject Heading and free-text terms with various synonyms was used to reflect the concepts of MDS and luspatercept as shown in the supplemental Materials. Search terms were defined and processed by a librarian (A.A.G.) with special expertise in systematic reviews, in conjunction with the investigators. In addition, we conducted a gray literature search by exploring the references and bibliographies of each included study to ensure all relevant studies are captured.19,20

Study selection

After removing duplicate publications across databases, studies were screened for inclusion using title and abstract, followed by full-text evaluation of potentially eligible studies. Eligible studies were clinical trials, retrospective studies, and case series with >15 RBC-TD patients that investigated the role of luspatercept in the management of patients with RBC-TD LR-MDS. Conference abstracts were included if they otherwise reported sufficient data. Studies were excluded if any of the following criteria were met: (1) study investigated luspatercept in diseases other than LR-MDS; (2) review articles, meta-analyses, or systematic reviews; (3) preclinical studies; (4) duplicate publications from the same cohort of patients; (5) studies that included >50% of non RBC-TD patients; (6) studies with insufficient reported data regarding the primary outcome of RBC-TI; and (7) studies published in languages other than English. The eligibility of each study was evaluated by 2 independent reviewers (A.A. and N.L.W.), with conflicts regarding inclusion between the 2 reviewers resolved by a third reviewer (J.P.B.).

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by 2 reviewers (A.A. and N.L.W.) using a standardized Excel spreadsheet developed specifically for this study. From each eligible study, we collected key characteristics including the first author’s name, year of publication, clinical trial identifier, study design, and details of the study arms. Patient demographics, such as sample size, number and percentage of female participants, and mean and median age, were recorded when available. We also extracted information on prior treatments, including the use of ESAs and iron chelation therapy, as well as baseline laboratory values such as hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, and serum erythropoietin levels. Transfusion burden before treatment initiation and treatment allocation (eg, luspatercept or ESA) were also documented. Efficacy end points extracted included hematologic improvement in platelets and absolute neutrophil count at 24 weeks, RBC-TI at 8, 12, and 24 weeks, duration of TI, and hematologic improvement–erythroid (HI-E) response. We additionally collected International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) and revised IPSS risk stratifications, as well as information on RS status and mutational data. Safety outcomes were extracted for adverse events (AEs), including fatigue, diarrhea, asthenia, nausea, dizziness, back pain, peripheral edema, headache, dyspnea, arthralgia, hypertension, and serious AEs (SAEs).

The data extraction process was divided between the 2 reviewers. After the initial extraction, the other reviewer independently crosschecked a random sample of studies from each reviewer’s data set to ensure accuracy and consistency, and any discrepancies identified were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Quality assessment

Two independent investigators (A.A. and N.L.W.) evaluated the included studies using 2 different quality assessment checklists. The Downs and Black checklist was used for observational studies, with the following scores used to define study quality: excellent (26-28); good (20-25); fair (15-19); and poor (≤14). The Cochrane Quality Assessment for Randomized Clinical Trials was used for clinical trials.21 Each study was classified into 3 categories according to the risk of bias: “low risk of bias” (all domains are low), “moderate risk of bias” (at least 1 domain raises some concerns), and “high risk of bias” (at least 1 domain is judged as “high risk”).22

End point definitions

The primary end point was the proportion of patients achieving RBC-TI at 8 weeks, which was defined as the absence of RBC transfusions within an 8-week period following the use of luspatercept. Secondary end points included RBC-TI at 12 and 24 weeks, defined as the proportion of patients who, after receiving ESA or luspatercept, no longer required any RBC transfusions for 12 and 24 weeks, respectively. HI-E at 8 weeks was assessed in RBC-TI patients and required a hemoglobin improvement of at least 1.5 g/dL that was sustained for a minimum of 8 weeks.23 Finally, AE occurrence was recorded as the percentage of patients who developed any drug-related AE during the treatment period.

Statistical analysis

A random effect model was used to pool percentages from single-arm studies, the rates of RBC-TI and HI-E, and the safety profile. Each study was weighted using the log ratio of individual study estimates weighted by sample size. Heterogeneity was evaluated using both I2 and Cochran Q. Study heterogeneity was categorized into 3 classes according to I2 (low heterogeneity, I2 < 30%; moderate heterogeneity, I2 = 30%-60%; high heterogeneity, I2 > 60%).24 All subgroup analyses were performed in the same manner, and a meta-regression model was used as a sensitivity analysis in case of heterogeneity (I2 > 30%). Finally, to test for publication bias, a funnel plot and rank test were used to statistically evaluate the funnel plot for publication bias.25 The Baujat plot was used to visualize the study that reported outlier results; all statistical analyses were conducted on R software version 4.3.3.26

Results

Results of the literature search and study selection

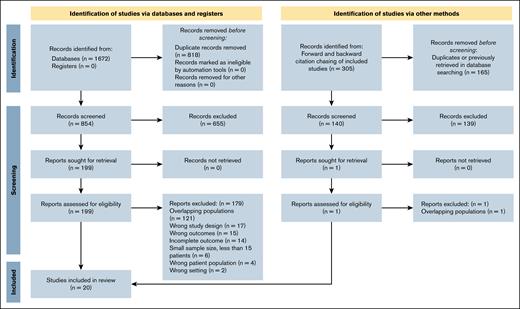

Our comprehensive search identified 1672 records across all databases, with 854 unique studies remaining after the removal of duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 655 studies were excluded, leaving 199 studies for full-text assessment. Of these, 180 were excluded for the following reasons: incorrect study setting (n = 2), not reporting primary outcome of interest (n = 15), excluded due to study design (n = 17), incomplete reporting of primary outcome (n = 14), excluded due to nontarget patient population (n = 4), <15 patients in the cohort (n = 6), and duplicated cohort from a different study (n = 121; supplemental Table 3). An additional 305 citations were identified using citation chasing, of which 1 study was evaluated by full-text review but ultimately removed due to duplicate reporting of the same cohort in a different study. Ultimately, 20 studies fulfilled all eligibility criteria and were incorporated into this systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

PRISMA flowchart of the studies included in the meta-analysis. This PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrates the study selection process for the systematic review evaluating the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in LR-MDS.

PRISMA flowchart of the studies included in the meta-analysis. This PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrates the study selection process for the systematic review evaluating the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in LR-MDS.

Study characteristics

Of the 20 studies included in this review, 7 were clinical trials, and 13 were cohort studies.12,13,16,27-40 Based on quality assessment, 10 studies were rated as excellent, 8 as good, 1 as fair, and 1 as poor. A detailed summary of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Included studies’ characteristics

| Author (year) . | Study design . | Center . | Patients, n . | Age, y . | Population characteristics . | Previous Tx/current Tx . | Outcome of interest . | Main result . | Quality assessment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Della Porta et al13 (2024) | RCT (phase 3) Full article | Multi | 363 (Lusp, 182; ESA, 181) | Med: 74 | ESA naïve and RS+: 73% IPSS-R: LR | N/A | Primary outcome: 12-week TI Secondary outcome: 8-week HI-E and TI at 8, 24, and 48 weeks, and safety profile | Lusp 12-week TI: 60% ESA 12-week TI: 35% | Excellent |

| Fenaux et al16 (2020) | RCT (phase 3) Full article | Multi | 153 (Lusp, 76; placebo, 76) | Med: 71 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk ESA refractory and RS+ | ESA and ICA/N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI, HI-E, and safety profile | Lusp 8-week TI: 38% Placebo 8-week TI: 13% | Excellent |

| Patel et al5 (2024) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Multi | 240 Lusp | Mean: 75.4 | ESA exposed (relapsed/refractory) | ESA and other (–)/N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-, 16-, and 24-week TI | 8-week TI: 64.2% | Good |

| Patel et al41 (2023) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Multi | 279 Lusp | Med: 76 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk ESA (naïve, refractory, or relapsed) | Lusp: 1L (30), 2L (202), and 3L (59)/1L (7 ESA), 2L (39 ESA and 5 HMA/IMID), and 3L (13 ESA, 10 HMA, and 3 IMID) | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-, 16-, and 24-week TI | 1L: 77% at 8-week TI 2L: 66% at 8-week TI 3L: 58% at 8-week | Good |

| Platzbecker et al42 (2022) | CT (phase 2) Full article | Multi | 74 | Med: 72.5 | IPSS-R: VL, L, I risk RS+/– | ESA 43.2%, ICA 31.9%, and IMID 9.5% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 8-week HI-E and safety profile | 8-week TI: 43.8% | Excellent |

| Al Ali et al28 (2023) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Single (MCC) | 28 | Med: 72 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– ESA + Lusp | Primary failure Lusp, n = 18; secondary failure Lusp, n = 7; and Lusp + ESA failure, n = 3/Lusp + ESA, n = 28 | Primary outcome: HI | HI was 36% | Fair |

| Batra et al30 (2023) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 592 | Mean: 69.6 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | N/A | Primary outcome: AEs | Fatigue is the most common | Good |

| Ades et al27 (2024) | CT (phase 2) Abstract | N/A | 24 | Med: 77.7 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS– | ESA, 100%/Lusp + ESA | Primary outcome: 8-week TI | 8-week TI: 29% | Good |

| Andritsos et al29 (2025) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 871 | Mean: 74.7 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 84.7%/Lusp only and Lusp + ESA | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12- and 24-week TI and HI | 8-week TI for TD (Lusp only and Lusp + ESA): 64.2% | Excellent |

| Bouchla et al31 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 98 | Mean: 75 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 95/98 | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI and AEs | 8-week TI (HTB, 25%; ITB, 57%; LTB, 69%) | Good |

| Chang et al12 (2025) | CT (phase 2) Full article | Multi | 37 | Med: 65 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+ | ESA, 57% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI, HI, and AEs | 8-week TI: 60% | Good |

| Comont et al32 (2023) | Prosp Cohort Abstract | Multi | 108 | Med: 70 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 100%; others, 44% | Primary outcome: 8-week HI-E | 8-week HI-E: 39% | Excellent |

| Consagra et al33 (2025) | CT Full article | Single (MCC) | 331 | Med: 75 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 95.8%; HMA, 15.7%; IMID, 11.5% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: increase in Hb 1.5 g/dL | 8-week TI: 16.6% | Excellent |

| Götze et al34 (2024) | RCT (phase 3) Abstract | Multi | 41 | Med: 72 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+ Max Lusp dose | N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: AEs | 8-week TI: 45.5% | Excellent |

| Heyrman et al35 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 77 | Med: 79 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 70.1% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI | 8-week TI: 35.4% | Good |

| Jonasova et al36 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 56 | Med: 74 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 83.3% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12- and 24-week HI-E | 8-week TI: 62.7% | Poor |

| Komrokji et al37 (2022) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Single (MCC) | 114 | Med: 70 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 89% | Primary outcome: HI Secondary outcome: TI | HI: 39.5% | Excellent |

| Lanino et al38 (2023) | Retro Cohort Full article | Single (Rozzano) | 215 | Med: 74 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI | 8-week TI (follow-up 24 week): 30.3% | Excellent |

| Leonard et al39 (2024) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Multi | 62 | Med: 78 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | N/A | Primary outcome: HI | HI, 48% | Good |

| Mukherjee et al43 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 253 | Med, 73.3 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk | ESA, 87% | Primary outcome: TI at 8 weeks Secondary outcome: HI | 8-week TI: 79.4% (LTB, 89.9%; HTB, 58.3%) | Excellent |

| Author (year) . | Study design . | Center . | Patients, n . | Age, y . | Population characteristics . | Previous Tx/current Tx . | Outcome of interest . | Main result . | Quality assessment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Della Porta et al13 (2024) | RCT (phase 3) Full article | Multi | 363 (Lusp, 182; ESA, 181) | Med: 74 | ESA naïve and RS+: 73% IPSS-R: LR | N/A | Primary outcome: 12-week TI Secondary outcome: 8-week HI-E and TI at 8, 24, and 48 weeks, and safety profile | Lusp 12-week TI: 60% ESA 12-week TI: 35% | Excellent |

| Fenaux et al16 (2020) | RCT (phase 3) Full article | Multi | 153 (Lusp, 76; placebo, 76) | Med: 71 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk ESA refractory and RS+ | ESA and ICA/N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI, HI-E, and safety profile | Lusp 8-week TI: 38% Placebo 8-week TI: 13% | Excellent |

| Patel et al5 (2024) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Multi | 240 Lusp | Mean: 75.4 | ESA exposed (relapsed/refractory) | ESA and other (–)/N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-, 16-, and 24-week TI | 8-week TI: 64.2% | Good |

| Patel et al41 (2023) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Multi | 279 Lusp | Med: 76 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk ESA (naïve, refractory, or relapsed) | Lusp: 1L (30), 2L (202), and 3L (59)/1L (7 ESA), 2L (39 ESA and 5 HMA/IMID), and 3L (13 ESA, 10 HMA, and 3 IMID) | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-, 16-, and 24-week TI | 1L: 77% at 8-week TI 2L: 66% at 8-week TI 3L: 58% at 8-week | Good |

| Platzbecker et al42 (2022) | CT (phase 2) Full article | Multi | 74 | Med: 72.5 | IPSS-R: VL, L, I risk RS+/– | ESA 43.2%, ICA 31.9%, and IMID 9.5% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 8-week HI-E and safety profile | 8-week TI: 43.8% | Excellent |

| Al Ali et al28 (2023) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Single (MCC) | 28 | Med: 72 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– ESA + Lusp | Primary failure Lusp, n = 18; secondary failure Lusp, n = 7; and Lusp + ESA failure, n = 3/Lusp + ESA, n = 28 | Primary outcome: HI | HI was 36% | Fair |

| Batra et al30 (2023) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 592 | Mean: 69.6 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | N/A | Primary outcome: AEs | Fatigue is the most common | Good |

| Ades et al27 (2024) | CT (phase 2) Abstract | N/A | 24 | Med: 77.7 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS– | ESA, 100%/Lusp + ESA | Primary outcome: 8-week TI | 8-week TI: 29% | Good |

| Andritsos et al29 (2025) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 871 | Mean: 74.7 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 84.7%/Lusp only and Lusp + ESA | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12- and 24-week TI and HI | 8-week TI for TD (Lusp only and Lusp + ESA): 64.2% | Excellent |

| Bouchla et al31 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 98 | Mean: 75 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 95/98 | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI and AEs | 8-week TI (HTB, 25%; ITB, 57%; LTB, 69%) | Good |

| Chang et al12 (2025) | CT (phase 2) Full article | Multi | 37 | Med: 65 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+ | ESA, 57% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI, HI, and AEs | 8-week TI: 60% | Good |

| Comont et al32 (2023) | Prosp Cohort Abstract | Multi | 108 | Med: 70 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 100%; others, 44% | Primary outcome: 8-week HI-E | 8-week HI-E: 39% | Excellent |

| Consagra et al33 (2025) | CT Full article | Single (MCC) | 331 | Med: 75 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 95.8%; HMA, 15.7%; IMID, 11.5% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: increase in Hb 1.5 g/dL | 8-week TI: 16.6% | Excellent |

| Götze et al34 (2024) | RCT (phase 3) Abstract | Multi | 41 | Med: 72 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+ Max Lusp dose | N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: AEs | 8-week TI: 45.5% | Excellent |

| Heyrman et al35 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 77 | Med: 79 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 70.1% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI | 8-week TI: 35.4% | Good |

| Jonasova et al36 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 56 | Med: 74 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 83.3% | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12- and 24-week HI-E | 8-week TI: 62.7% | Poor |

| Komrokji et al37 (2022) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Single (MCC) | 114 | Med: 70 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | ESA, 89% | Primary outcome: HI Secondary outcome: TI | HI: 39.5% | Excellent |

| Lanino et al38 (2023) | Retro Cohort Full article | Single (Rozzano) | 215 | Med: 74 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | N/A | Primary outcome: 8-week TI Secondary outcome: 12-week TI | 8-week TI (follow-up 24 week): 30.3% | Excellent |

| Leonard et al39 (2024) | Retro Cohort Abstract | Multi | 62 | Med: 78 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk RS+/– | N/A | Primary outcome: HI | HI, 48% | Good |

| Mukherjee et al43 (2024) | Retro Cohort Full article | Multi | 253 | Med, 73.3 | IPSS-R: VL, L, and I risk | ESA, 87% | Primary outcome: TI at 8 weeks Secondary outcome: HI | 8-week TI: 79.4% (LTB, 89.9%; HTB, 58.3%) | Excellent |

1L, first line of therapy; CT, clinical trial; HMA, hypomethylating agent; HTB, high transfusion burden; ICA, immunosuppressive chemotherapy agent; I, intermediate; IMID, immunomodulatory drug; IPSS-R, revised IPSS; L, low; Lusp, luspatercept; Max, maximum; MCC, Moffitt Cancer Center; Med, median; N/A, not applicable; Prosp, prospective; RCT, randomized controlled trial; Retro, retrospective; Tx, treatment; VL, very low.

Pooled patient characteristics

Across the 20 studies included in the meta-analysis, a total of 3455 patients received luspatercept. The mean age was 73.6 years, with 41.5% of patients being female. Among these patients, 89.5% were classified as having very low or low risk disease according to revised IPSS, 67.4% were RS+, and 76.4% had a history of ESA use (Table 2).

General characteristics of the pooled patients

| Variable . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 3455 |

| Female, % | 41.5 |

| Mean age, y | 73.6 |

| IPSS-R risk, % | |

| Very low | 22.49 |

| Low | 67.07 |

| Total | 89.55 |

| RS+, % | 67.39 |

| Prior ESA exposure, % | 76.41 |

| Variable . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 3455 |

| Female, % | 41.5 |

| Mean age, y | 73.6 |

| IPSS-R risk, % | |

| Very low | 22.49 |

| Low | 67.07 |

| Total | 89.55 |

| RS+, % | 67.39 |

| Prior ESA exposure, % | 76.41 |

Percentages are calculated based on pooled patient-level data across all included studies. IPSS-R risk categories were reported when available; Total IPSS-R (very low + low) reflects the proportion of patients with LR-MDS per IPSS-R. ESA history refers to patients with any previous exposure to ESAs before luspatercept treatment.

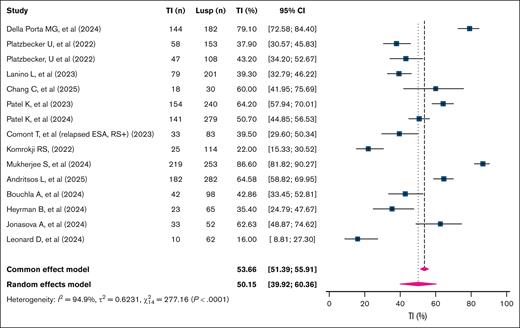

RBC-TI at 8 weeks

The overall 8-week RBC-TI rate was 50.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 39.9-60.4; k = 15 studies; n = 2090 patients; I2 = 94.9%; Figure 2). The 8-week TI rate among studies focusing on RS+ patients was significantly higher than that of RS– patients, at 57.9% (95% CI, 47.4-67.7; k = 8; n = 765; I2 = 86%) vs 43.0% (95% CI, 30.3-56.7; k = 4; n = 383; I2 = 81.2%), respectively (P = .004; supplemental Figure 1).

Pooled 8-week TI rates in patients with TD LR-MDSs treated with luspatercept. This forest plot displays the pooled 8-week TI rates across individual studies evaluating Lusp in patients with TD LR-MDSs. Each square represents the point estimate of TI rate for an individual study, with the horizontal bars indicating 95% CIs. The size of the squares reflects the weight of each study in the meta-analysis. The diamond at the bottom represents the overall pooled estimate, with its width indicating the 95% CI. A random-effects model was used due to interstudy heterogeneity. Lusp, luspatercept.

Pooled 8-week TI rates in patients with TD LR-MDSs treated with luspatercept. This forest plot displays the pooled 8-week TI rates across individual studies evaluating Lusp in patients with TD LR-MDSs. Each square represents the point estimate of TI rate for an individual study, with the horizontal bars indicating 95% CIs. The size of the squares reflects the weight of each study in the meta-analysis. The diamond at the bottom represents the overall pooled estimate, with its width indicating the 95% CI. A random-effects model was used due to interstudy heterogeneity. Lusp, luspatercept.

Furthermore, studies that included only patients with a low transfusion burden (LTB; defined as <4 units per 16 weeks before treatment initiation) demonstrated significantly higher 8-week RBC-TI rates than those with a high transfusion burden (≥4 units per 16 weeks before treatment initiation): 72.9% (95% CI, 60.4-82.6; k = 3; n = 45; I2 = 0%) vs 38.7% (95% CI, 24.1-55.7; k = 4; n = 165; I2 = 77.1%; P = .004; supplemental Figure 1).

In addition, studies that included mixed cohorts with varying RS status and transfusion burden reported a pooled 8-week RBC-TI rate of 47.6% (95% CI, 36.4-59.0; k = 12; n = 1789; I2 = 95%; supplemental Figure 1).

Moreover, evaluating differences in terms of RS status and the ESA status showed no statistically significant differences between subgroups (P = .295), with the highest 8-week RBC-TI rate seen in studies evaluating ESA-naïve RS+ patients at 70.2% (95% CI, 50.0-86.7; k = 2; n = 212; I2 = 84.5%), followed by studies on ESA-refractory RS+ patients at 49.5% (95% CI, 41.5-57.5; k = 8; n = 789; I2 = 78.7%; supplemental Figure 2).

However, studies including both RS+ and RS– patients showed a rate of 49.4% (95% CI, 36.6-62.2; k = 10; n = 1553; I2 = 95.4%), whereas ESA-refractory RS– patients had the lowest rate at 45.0% (95% CI, 30.3-56.7; k = 4; n = 383; I2 = 81.2%; supplemental Figure 2).

RBC-TI at 12 weeks

The overall 12-week TI rate was 57.0% (95% CI, 48.1-65.5; k = 11; n = 1431; I2 = 90%; Figure 3). Meta-regression analysis revealed that a history of ESA use negatively affected 12-week RBC-TI rates (P < .001). This finding was further supported by subgroup analysis, because studies in which >90% of patients with prior ESA exposure had significantly lower 12-week RBC-TI rates than those with <90% ESA exposure: 43.1% (95% CI, 34.8-51.9; k = 5; n = 1335; I2 = 89.6%) vs 58% (95% CI, 49.4-66.1; k = 5; n = 576; I2 = 67.0%; P = .017; supplemental Figure 3).

Pooled 12-week TI rates in patients with TD LR-MDSs treated with luspatercept. This forest plot presents the pooled 12-week TI rates from studies evaluating Lusp in patients with TD LR-MDSs. Each blue square indicates the point estimate for an individual study, with the horizontal lines representing 95% CIs. Square sizes are proportional to the study weights in the meta-analysis. The diamond at the bottom represents the overall estimate derived using a random-effects model. Lusp, luspatercept.

Pooled 12-week TI rates in patients with TD LR-MDSs treated with luspatercept. This forest plot presents the pooled 12-week TI rates from studies evaluating Lusp in patients with TD LR-MDSs. Each blue square indicates the point estimate for an individual study, with the horizontal lines representing 95% CIs. Square sizes are proportional to the study weights in the meta-analysis. The diamond at the bottom represents the overall estimate derived using a random-effects model. Lusp, luspatercept.

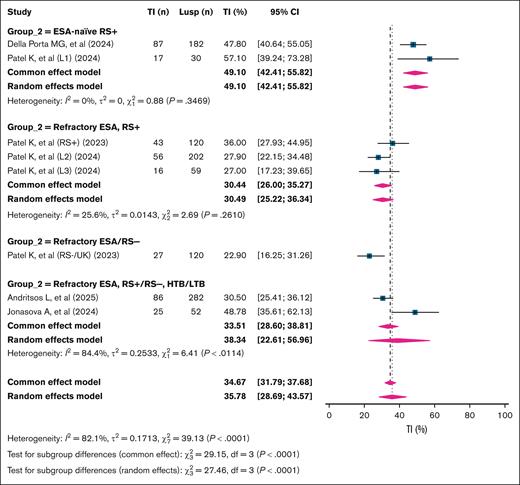

RBC-TI at 24 weeks

The overall 24-week RBC-TI rate was 35.8% (95% CI, 28.7-43.6; k = 8; n = 1047; I2 = 82.1%). Subgroup analysis based on patient characteristics revealed significant differences in response rates (P < .001). The highest 24-week RBC-TI was observed in ESA-naïve RS+ patients at 49.1% (95% CI, 42.4-55.8; k = 2; n = 212; I2 = 0%). In contrast, ESA-refractory RS+ patients showed a lower RBC-TI rate of 30.5% (95% CI, 25.2-36.3; k = 3; n = 381; I2 = 25.6%). Studies that included both ESA-naïve and -refractory RS+ patients reported an RBC-TI rate of 38.3% (95% CI, 22.6-57.0; k = 2; n = 334; I2 = 84.4%). Notably, the lowest 24-week TI rate was observed in ESA-refractory RS– patients, at 22.9% (95% CI, 16.2-31.2; n = 120; single study; Figure 4).

Pooled 24-week TI rates in patients with LR-MDS treated with luspatercept, stratified by ESA exposure and RS status. This forest plot summarizes subgroup-specific 24-week TI rates in patients with TD LR-MDS treated with Lusp. Subgroups were defined based on ESA exposure and RS status: ESA naïve, RS+; refractory ESA, RS+; refractory ESA/RS–; and refractory ESA, RS+/RS–, and HTB/LTB mixed populations. Each study is presented with its point estimate and 95% CI, and pooled estimates are shown in a diamond at the bottom using both fixed-effect and random-effects models. Group 2 is the variable that is used to subgroup the studies that built over the included population of patients in the study, as shown in the figure. HTB, high transfusion burden; Lusp, luspatercept.

Pooled 24-week TI rates in patients with LR-MDS treated with luspatercept, stratified by ESA exposure and RS status. This forest plot summarizes subgroup-specific 24-week TI rates in patients with TD LR-MDS treated with Lusp. Subgroups were defined based on ESA exposure and RS status: ESA naïve, RS+; refractory ESA, RS+; refractory ESA/RS–; and refractory ESA, RS+/RS–, and HTB/LTB mixed populations. Each study is presented with its point estimate and 95% CI, and pooled estimates are shown in a diamond at the bottom using both fixed-effect and random-effects models. Group 2 is the variable that is used to subgroup the studies that built over the included population of patients in the study, as shown in the figure. HTB, high transfusion burden; Lusp, luspatercept.

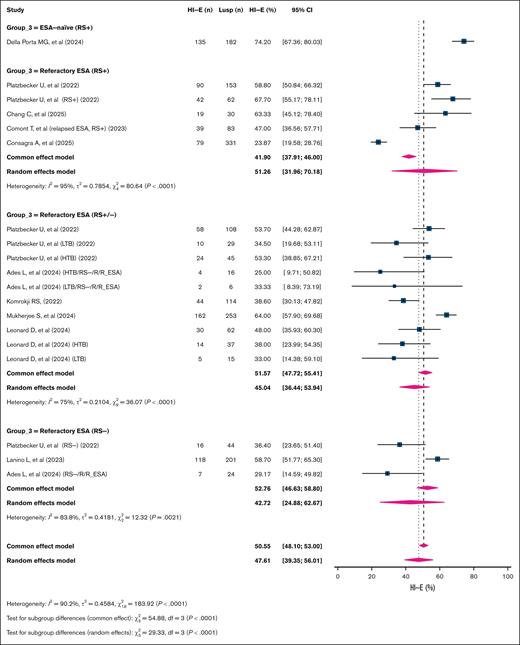

HI-E

The overall HI-E rate was 51.3% (95% CI, 41.3-61.2; k = 12; n = 1647; I2 = 93%). Subgroup analysis based on patient characteristics demonstrated significant differences in HI-E rates (P < .001), with the highest HI-E rate observed in ESA-naïve RS+ patients at 74.2% (95% CI, 67.4-80.0; k = 1; n = 182). This was followed by ESA-refractory RS+ patients, with a rate of 51.3% (95% CI, 32-70.2; k = 5; n = 659; I2 = 95%), and studies including ESA-refractory patients with mixed RS status (RS+/–), which showed a similar HI-E rate of 51.5% (95% CI, 39.5-63.6; k = 4; n = 537; I2 = 86.0%). The lowest HI-E rate was seen in ESA-refractory, RS– patients at 42.7% (95% CI, 24.9-62.7; k = 3; n = 269; I2 = 83.8%; Figure 5).

Pooled HI-E response rates per International Working Group (IWG) 2018 criteria in patients with LR-MDS treated with luspatercept. This forest plot depicts HI-E response rates based on the IWG 2018 criteria in patients with TD LR-MDS treated with Lusp. Studies were stratified into 4 clinical subgroups: ESA naïve, RS+; refractory ESA, RS+ with HTB/LTB; refractory ESA, RS+/RS– mixed; and refractory ESA, RS–. Each square represents the HI-E rate from an individual study, with horizontal lines showing 95% CIs; the size of each square reflects the weight of that study in the meta-analysis. Diamonds denote the pooled estimates from fixed-effect and random-effects models for each subgroup and overall. Group 3 is the variable that is used to subgroup the studies that built over the included population of patients in the study, as shown in the figure. Lusp, luspatercept.

Pooled HI-E response rates per International Working Group (IWG) 2018 criteria in patients with LR-MDS treated with luspatercept. This forest plot depicts HI-E response rates based on the IWG 2018 criteria in patients with TD LR-MDS treated with Lusp. Studies were stratified into 4 clinical subgroups: ESA naïve, RS+; refractory ESA, RS+ with HTB/LTB; refractory ESA, RS+/RS– mixed; and refractory ESA, RS–. Each square represents the HI-E rate from an individual study, with horizontal lines showing 95% CIs; the size of each square reflects the weight of that study in the meta-analysis. Diamonds denote the pooled estimates from fixed-effect and random-effects models for each subgroup and overall. Group 3 is the variable that is used to subgroup the studies that built over the included population of patients in the study, as shown in the figure. Lusp, luspatercept.

Safety profile of luspatercept

The most frequently reported AE was peripheral edema, with a pooled incidence of 17.8% (95% CI, 11.4-26.8; k = 3; n = 365; I2 = 65.9%) from clinical trial data, followed by diarrhea, observed in 15.6% of patients (95% CI, 8.2-27.7; k = 4; n = 473; I2 = 85.6%), and back pain, which occurred in 16.1% of patients (95% CI, 9.2-26.8; k = 2; n = 335; I2 = 76.7%). Fatigue was also a common AE, with a pooled estimate of 11.4% (95% CI, 5.4-22.6; k = 5; n = 1100; I2 = 93.6%), showing a significantly higher rate in clinical trials at 17.0% (95% CI, 8.4-31.6%; k = 3; n = 443; I2 = 89.7%) than real-world studies at 6.9% (95% CI, 5.2-9.1; k = 2; n = 657; I2 = 0%; P = .021). Dizziness had a pooled incidence of 12.3% (95% CI, 6.6-21.9; k = 4; n = 448; I2 = 79.0%), with significantly higher rates in clinical trials at 15.8% (95% CI, 9.2-25.6; k = 3; n = 365; I2 = 71.9%) than real-world data at 4.8% (95% CI, 9.2-25.6; k = 1; n = 83; I2 = 0%; P = .029). Headache was reported in 11.2% of patients (95% CI, 6.1-19.5; k = 3; n = 448; I2 = 74.9%), with a significantly higher incidence in clinical trials at 14.1% (95% CI, 8.7-22.0; k = 2; n = 365) than real-world studies at 4.9% (95% CI, 1.8-12.2; k = 1; n = 83; I2 = 0%; P = .043). Asthenia occurred in 5.3% of patients (95% CI, 1.9-14.1; k = 5; n = 507; I2 = 78.6%), with no significant differences between clinical trials (7.7%; 95% CI, 2.1-24.3) and real-world studies (3.1%; 95% CI, 1.2-7.8; P = .262). Dyspnea was reported in 2.1% of patients overall (95% CI, 0.3-14.6; k = 3; n = 927; I2 = 92.4%), with higher rates in clinical trials at 5.1% (95% CI, 1.0-22.7; k = 2; n = 335; I2 = 87.3%) than in real-world data at 2.1% (k = 1; n = 592; P = .011). Other AEs included arthralgia at 5.6% (95% CI, 2.2-13.5; k = 5; n = 1118; I2 = 90.6%), without a statistically significant difference between clinical trials and real-world studies (P = .666), and nausea, which had a pooled rate of 3.6% (95% CI, 0.2-45.7; k = 2; n = 335; I2 = 89.6%). Hypertension was reported in 3.0% of patients (95% CI, 0.6-12.6; k = 4; n = 947; I2 = 90.4%), with no significant difference between clinical trials and real-world data (P = .104). Finally, the pooled incidence of SAEs was 28.0% (95% CI, 12.8-50.7; k = 5; n = 1088; I2 = 97.2%), with no significant difference between clinical trial settings (32.1%; 95% CI, 15.5-54.8) and real-world cohorts (22.9%; 95% CI, 3.5-70.6; P = .691; Table 3).

Pooled analysis of AEs associated with luspatercept use in patients with LR-MDS

| AE . | Source type . | Pooled estimate (95% CI), % . | I2, % . | k . | n . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back Pain | CT | 16.1 (9.2-26.8) | 76.7 | 2 | 335 | |

| Fatigue | Combined | 11.4 (5.4-22.6) | 93.6 | 5 | 1100 | |

| Fatigue | CT | 17.0 (8.4-31.6) | 89.7 | 3 | 443 | .021 |

| Fatigue | RW | 6.9 (5.2-9.1) | 0 | 2 | 657 | |

| Dyspnea | Combined | 2.1 (0.3-14.6) | 92.4 | 3 | 927 | |

| Dyspnea | CT | 5.1 (1.0-22.7) | 87.3 | 2 | 335 | .011 |

| Dyspnea | RW | 2.1 (0.3-14.6) | 0 | 1 | 592 | |

| Asthenia | Combined | 5.3 (1.9-14.1) | 78.6 | 5 | 507 | |

| Asthenia | CT | 7.7 (2.1-24.3) | 80 | 3 | 359 | .262 |

| Asthenia | RW | 3.1 (1.2-7.8) | 0 | 2 | 148 | |

| Dizziness | Combined | 12.3 (6.6-21.9) | 79.0 | 4 | 448 | |

| Dizziness | CT | 15.8 (9.2-25.6) | 71.9 | 3 | 365 | .029 |

| Dizziness | RW | 4.8 (9.2-25.6) | 0 | 1 | 83 | |

| Nausea | CT | 3.6 (0.2-45.7) | 89.6 | 2 | 335 | |

| Headache | Combined | 11.2 (6.1-19.5) | 74.9 | 3 | 448 | |

| Headache | CT | 14.1 (8.7-22.0) | 74.9 | 2 | 365 | .043 |

| Headache | RW | 4.9 (1.8-12.2) | 0 | 1 | 83 | |

| Hypertension | Combined | 3.0 (0.6-12.6) | 90.4 | 4 | 947 | |

| Hypertension | CT | 7.4 (2.2-22.2) | 81.8 | 2 | 290 | .104 |

| Hypertension | RW | 1.1 (0.14-7.8) | 78.2 | 2 | 657 | |

| Diarrhea | CT | 15.6 (8.2-27.7) | 85.6% | 4 | 473 | |

| Peripheral Edema | CT | 17.8 (11.4-26.8) | 65.9 | 3 | 365 | |

| Arthralgia | Combined | 5.6 (2.2-13.5) | 90.6 | 5 | 1118 | |

| Arthralgia | CT | 7.5 (3.5-15.2) | 76.7 | 3 | 443 | .666 |

| Arthralgia | RW | 4.0 (0.2-44.1) | 96.9 | 2 | 675 | |

| SAE | Combined | 28.0 (12.8-50.7) | 97.2 | 5 | 1088 | .691 |

| SAE | CT | 32.1 (15.5-54.8) | 93.7 | 3 | 413 | |

| SAE | RW | 22.9 (3.5-70.6) | 98.5 | 2 | 675 |

| AE . | Source type . | Pooled estimate (95% CI), % . | I2, % . | k . | n . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back Pain | CT | 16.1 (9.2-26.8) | 76.7 | 2 | 335 | |

| Fatigue | Combined | 11.4 (5.4-22.6) | 93.6 | 5 | 1100 | |

| Fatigue | CT | 17.0 (8.4-31.6) | 89.7 | 3 | 443 | .021 |

| Fatigue | RW | 6.9 (5.2-9.1) | 0 | 2 | 657 | |

| Dyspnea | Combined | 2.1 (0.3-14.6) | 92.4 | 3 | 927 | |

| Dyspnea | CT | 5.1 (1.0-22.7) | 87.3 | 2 | 335 | .011 |

| Dyspnea | RW | 2.1 (0.3-14.6) | 0 | 1 | 592 | |

| Asthenia | Combined | 5.3 (1.9-14.1) | 78.6 | 5 | 507 | |

| Asthenia | CT | 7.7 (2.1-24.3) | 80 | 3 | 359 | .262 |

| Asthenia | RW | 3.1 (1.2-7.8) | 0 | 2 | 148 | |

| Dizziness | Combined | 12.3 (6.6-21.9) | 79.0 | 4 | 448 | |

| Dizziness | CT | 15.8 (9.2-25.6) | 71.9 | 3 | 365 | .029 |

| Dizziness | RW | 4.8 (9.2-25.6) | 0 | 1 | 83 | |

| Nausea | CT | 3.6 (0.2-45.7) | 89.6 | 2 | 335 | |

| Headache | Combined | 11.2 (6.1-19.5) | 74.9 | 3 | 448 | |

| Headache | CT | 14.1 (8.7-22.0) | 74.9 | 2 | 365 | .043 |

| Headache | RW | 4.9 (1.8-12.2) | 0 | 1 | 83 | |

| Hypertension | Combined | 3.0 (0.6-12.6) | 90.4 | 4 | 947 | |

| Hypertension | CT | 7.4 (2.2-22.2) | 81.8 | 2 | 290 | .104 |

| Hypertension | RW | 1.1 (0.14-7.8) | 78.2 | 2 | 657 | |

| Diarrhea | CT | 15.6 (8.2-27.7) | 85.6% | 4 | 473 | |

| Peripheral Edema | CT | 17.8 (11.4-26.8) | 65.9 | 3 | 365 | |

| Arthralgia | Combined | 5.6 (2.2-13.5) | 90.6 | 5 | 1118 | |

| Arthralgia | CT | 7.5 (3.5-15.2) | 76.7 | 3 | 443 | .666 |

| Arthralgia | RW | 4.0 (0.2-44.1) | 96.9 | 2 | 675 | |

| SAE | Combined | 28.0 (12.8-50.7) | 97.2 | 5 | 1088 | .691 |

| SAE | CT | 32.1 (15.5-54.8) | 93.7 | 3 | 413 | |

| SAE | RW | 22.9 (3.5-70.6) | 98.5 | 2 | 675 |

P values represent the statistical significance of differences in AE rates between CT and RW sources when applicable. Only pooled estimates with stratified source analysis (CT vs RW) are accompanied by a P value. Combined represents combined CT and RW data.

CT, clinical trial; RW, real-world study.

Publication bias

The assessment of publication bias using the rank correlation test revealed no statistically significant evidence of bias (P = .611; supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in patients with RBC TD LR-MDS. Our findings demonstrate an 8-week RBC-TI rate of 50.2%, with significantly higher responses observed among patients with MDS and RS+ (57.9%) and those with LTB (72.9%), consistent with prior clinical trial outcomes.13 As treatment options for patients with LR-MDS who have anemia expand, important questions are emerging regarding optimal treatment selection and sequencing.44 However, direct head-to-head comparisons are lacking, and crosstrial evaluations between available therapies are challenging due to differences in patient and disease characteristics across clinical trials, particularly with respect to RS+ status, del(5q), and previous ESA exposure.

Given these limitations, an indirect comparison between imetelstat and luspatercept was only feasible for RS+ TD patients with LR-MDS in the second-line setting (ie, those refractory or relapsed after ESAs), because data on imetelstat in other clinical contexts remain limited.40 Our analysis showed that luspatercept and imetelstat have comparable 8-week RBC-TI rates in this setting: 49.5% for luspatercept vs 47% for imetelstat.40 However, luspatercept demonstrated a more pronounced benefit in the LTB subgroup, achieving an RBC-TI rate of 72.9% compared to the 45% reported for imetelstat.40 In contrast, among patients with high transfusion burden, 8-week RBC-TI rates appeared to be comparable: 33.9% for imetelstat and 38.4% for luspatercept.40 Similarly, the 24-week RBC-TI rate in the second-line setting was comparable: 30.5% for luspatercept vs 28% for imetelstat.40 Notably, when assessed using the International Working Group 2018 criteria, HI-E in RS+ patients treated with luspatercept reached 51.3%, which was numerically higher than the 42% reported for imetelstat in this population.40

Furthermore, luspatercept demonstrated a favorable and manageable safety profile, with the most commonly reported AEs being peripheral edema, diarrhea, and back pain, whereas SAEs occurred in only 28% of patients and were generally manageable and not life threatening. Notably, the frequency of AEs was lower in real-world studies than clinical trials, indicating good tolerability in routine clinical practice. In contrast, other agents used in LR-MDS, such as imetelstat, low-dose azacitidine, and lenalidomide, have been associated with higher rates of hematologic toxicities, particularly thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, which increases the risk of serious infections and can potentially negatively affect long-term treatment adherence.40,45-47

Importantly, although short-term data suggest that luspatercept offers superior outcomes compared to ESAs in the frontline setting, its long-term clinical benefits remain unclear and require further follow-up and investigation. Furthermore, data on how patients’ molecular profiles influence (eg, the presence of SF3B1 and other genetic mutations) treatment response are still limited.13 Additionally, data on luspatercept’s effects on absolute neutrophil and platelet counts remain limited, despite their critical role in determining patient outcomes.48 Future studies should aim to address these gaps by examining luspatercept’s impact on hematologic parameters and exploring predictive molecular biomarkers of response beyond the presence of SF3B1 mutations. Moreover, despite its clinical advantages, luspatercept’s financial toxicity must be considered, especially given that no formal cost-effectiveness analyses have been published to assess whether luspatercept represents a cost-effective alternative to ESAs or other therapies in the LR-MDS setting. Future research should evaluate the health care resource utilization between luspatercept and other medications that focus on TI in patients with LR-MDS and create a comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis to evaluate the optimal strategy in managing those patients efficiently.

Additionally, data on optimal sequential therapy after loss of response to frontline luspatercept are extremely limited, because only a minority of patients in the IMerge trial, the pivotal trial that led to the approval of imetelstat, had received prior treatment with luspatercept.40 Emerging agents from the same class as luspatercept, such as elritercept, also warrant evaluation, although their optimal placement in treatment algorithms remains undefined.49

Beyond monotherapy, the potential of combination regimens involving luspatercept remains largely unexplored. Potential strategies involve combining luspatercept with agents such as imetelstat, ESAs, hypomethylating agents, or lenalidomide for patients with del (5q) MDS. However, emerging data support the safety and efficacy of combination treatment with ESA and luspatercept, leading to the prospective exploration of this combination in clinical trials (eg, NCT05181735).27 However, it remains unknown whether these combinations can deliver superior long-term outcomes compared to single-agent approaches, and a careful consideration of efficacy, toxicity, and financial burden is needed to guide optimal, patient-centered treatment decisions. Additional trials are also exploring the efficacy of luspatercept in patient populations previously excluded from clinical trials, such as patients with del(5q) (eg, NCT05924100) and those who are not RBC-TD (NCT05949684), which may expand its clinical utility.

Finally, there remains a notable unmet need for effective therapies in RS– patients, with current data suggesting that luspatercept may have limited efficacy in this subgroup. All these critical questions highlight the need for further research to define the most effective and personalized treatment strategies for managing patients with RBC-TD LR-MDS.

It is important to acknowledge that our study has several limitations. Firstly, the lack of access to patient-level data limited our ability to fully explore treatment effects across various subgroups. Second, several of the included studies were only available as conference abstracts, which provided limited detail and precluded robust subgroup or sensitivity analyses. This likely contributed to the moderate-to-high heterogeneity observed in several pooled estimates. Additionally, data on key clinical end points such as 16-week RBC-TI, progression to acute myeloid leukemia, and overall survival were not consistently reported across the analyzed studies, precluding their inclusion in our analysis. Moreover, there is a lack of high quality data on the efficacy of luspatercept in non-TD patients with LR-MDS with symptomatic anemia, but this question is currently being addressed in the ongoing randomized phase 3 ELEMENT trial (NCT05949684).50 Lastly, although some trials reported QOL data, the absence of a standardized methodology to translate QOL surveys into quality-adjusted life years precluded a comprehensive health economic evaluation.

In summary, this meta-analysis highlights the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in the treatment of TD LR-MDS, with the greatest benefit seen with therapy in the frontline (ESA-naïve) setting for patients whose MDS is RS+ and who have LTB. Luspatercept has demonstrated superior RBC-TI and HI-E rates compared to available alternatives, along with a more favorable safety profile, especially in real-world settings. These findings support the use of luspatercept for patients with TD LR-MDS for whom achieving early and sustained TI is the primary therapeutic goal.

Acknowledgments

J.M.S. is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (award number T32CA233414). B.R. received a Mildred-Scheel scholarship from the German Cancer Aid (“Deutsche Krebshilfe”; grant number 70114570). J.P.B. is supported by a grant from the Edward P. Evans Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: A.A. conceptualized the study, performed data extraction and meta-analysis, and drafted the manuscript; N.L.W. assisted with study screening, data extraction, and writing; B.R., J.M.S., A.M., L.M., and T.K. contributed to data interpretation and critical revisions; N.A.P., M.S., and A.M.Z. provided clinical expertise, critical feedback, and project supervision; A.A.G. developed and executed the literature search strategy, supported adherence to systematic review methodology, and drafted the manuscript; J.P.B. served as the senior supervisor and guided the project; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.M. serves as a consultant for Rigel. M.S. served on the advisory board for Novartis, Kymera, Sierra Oncology, GSK, Rigel, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Sobi, and Syndax; consulted for Boston Consulting Group and The Dedham Group; and participated in Continuing Medical Education activity for Novartis, Curis Oncology, Haymarket Media, and Clinical Care Options. A.M.Z. received research funding (institutional) from Celgene/BMS, AbbVie, Astex, Pfizer, Kura, Medimmune/AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Takeda, Novartis, Shattuck Labs, Geron, Foran, and Aprea; and advisory board fees, consultancy fees, clinical trial committee fees, and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Akesobio, Agios, Amgen, Astellas, BioCryst, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene/BMS, Chiesi/Cornerstone Biopharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Dr Reddy’s, Epizyme, Faron, FibroGen, GlaxoSmithKline, GlycoMimetics, Genentech, Gilead, Geron, Janssen, Jasper, Karyopharm, Kyowa Kirin, Keros, Kura, Novartis, Notable, Orum, Otsuka, Pfizer, Regeneron, Rigel, Seagen, Shattuck Labs, Schrödinger, Syros, Syndax, Servier, Takeda, Treadwell, Taiho, Vincerx, and Zentalis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jan Philipp Bewersdorf, Section of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine and Yale Cancer Center, 333 Cedar St, PO Box 208028, New Haven, CT 06520-8028; email: jan.bewersdorf@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

A.A. and N.L.W. contributed equally to this study and are joint co-first authors.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Jan Philipp Bewersdorf (jan.bewersdorf@yale.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.