Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hemolytic anemia that afflicts millions of people worldwide and continues to carry high morbidity and reduced life expectancy. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was the only standard-of-care option for cure before the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of 2 cellular drugs. Transfusion medicine plays a pivotal role in supporting patients through mobilization and apheresis collection of peripheral blood stem cells and through transplant using standard or exchange transfusion strategies. Despite these advances, obtaining sufficient cells to generate a cellular gene therapy product and lack of standardized protocols that describe the optimal preparative regimen, mobilization, and collection of stem cells present a significant barrier to success. Our working group, convened as part of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–funded Cure Sickle Cell Initiative, sought to identify gaps in our understanding of these processes to improve advanced cell therapies for SCD.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited hemolytic anemia that can profoundly affect the health and life span of affected patients.1 It is a hemoglobinopathy characterized by a base substitution in the β-globin gene that results in a single amino acid change leading to the production of hemoglobin S (HbS). HbS polymerizes when deoxygenated, causing the red blood cell (RBC) to assume a rigid sickle shape that contributes to anemia, vaso-occlusion, intravascular hemolysis, endothelial injury, and end-organ damage.2,3

Current therapies for SCD include supportive care for infections, disease-modifying medications to reduce the hemolytic burden or vasculopathy, and RBC transfusion.4 Until recently, allogeneic transplantation was the only potentially curative treatment option. The first successful transplants occurred ∼40 years ago with matched-sibling donors and resulted in stable engraftment and overall survival of >90%.5 However, <20% of patients with SCD have a matched-sibling donor leading to other donor sources being used with encouraging results.6,7 Despite the improved outcomes and survival in patients with SCD who have undergone allogeneic transplantation, the risks of graft-versus-host disease, among other factors, have hindered wider acceptance.8

Genetically manipulating autologous hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) may prove to be a promising transformative therapy without the risks associated with an allogeneic transplantation.9,10 The actualization of gene therapy for the treatment of SCD is a major medical accomplishment made possible by >30 years of basic science research advances such as viral vectors incorporating erythroid-specific regulatory elements and the development of CRISPR/CRISPR–associated protein 9 tools.1,10,11 Gene therapy relies on the stem cell transplantation of gene-modified autologous HSCs that have been manipulated ex vivo. The optimal gene-modified cell dose is unknown; however, the target dose for transplantation in most clinical trials ranges between 3 to 4 million CD34+ cells per kg. To achieve this final cell dose at the end of manufacturing, relatively large numbers of HSCs need to be collected (15-25 million CD34+ cells per kg) in many protocols.12-14 High numbers of CD34+ cells are needed in the starting material because apheresis hematopoietic progenitor cell collections first undergo CD34+ selection (with a typical recovery of 50% input) followed by transduction or electroporation, which further reduces the number of CD34+ cells resulting in a final drug product dose as low as 25% of the initial collected material.15 There are many inherent requirements to generate an optimal cell therapy product including (a) obtaining sufficient HSCs for ex vivo manipulation, (b) ideal timing of HSC collection after mobilization, (c) enrichment and manipulation of collected HSCs, and (d) facilitating patient access to advanced medical care. Initial approaches in gene therapy used bone marrow (BM) as an HSC source; however, this resulted in relatively low numbers of HSCs obtained, with many CD34+ cells expressing dim levels of CD90, cell surface markers not typically associated with long-term reconstitution.15,16 BM collections were abandoned from studies because they were associated with significant patient pain and morbidity and clinical outcomes were suboptimal.12,17 Peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection by apheresis is an alternative approach, but in patients with SCD, traditional mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was associated with significant adverse events such as vaso-occlusive events (VOEs), multiorgan failure, and even death.17 The use of apheresis became more feasible with the introduction of plerixafor for mobilization.18 Although plerixafor-mobilized PBSC collections acquire greater numbers of higher quality CD34+ bright HSCs than BM collections in patients with SCD, suboptimal collections continue to necessitate multiple procedures.15 Despite multiple procedures and cycles of collection, for some patients, sufficient HSCs still cannot be collected to generate a gene therapy product for transplantation.13

The Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (CureSCi) is a collaborative, patient-focused research effort designed to accelerate the advancement of genetic-based cures for SCD. The initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. As part of this effort, CureSCi convened an Apheresis Working Group (AWG) comprising individuals from academic, community, industry, and government organizations to better understand the challenges associated with mobilization and apheresis collection of HSCs in patients with SCD. The goal of the AWG is to establish best-practice guidelines to enable a more efficient and consistent approach to obtaining HSCs from patients with SCD. To this end, the AWG has been working on evaluating the knowledge gaps and possible solutions with regards to performing apheresis procedures (both PBSC collection and red cell exchange [RCE]) in patients with SCD. The purpose of this paper is to discuss considerations and challenges associated with preparing patients with SCD for mobilization and PBSC collection for gene therapy and highlight areas of investigation to improve future therapies.

Practice variability among participating collection sites

In 2021, a survey was generated in Qualtrics (Provo, UT) with the goal of identifying areas of variation in PBSC collection practices that would serve as a guide in establishing best-practice guidelines to maximize collection efficiencies. The 34-question survey was developed by the CureSCi AWG members based on their personal experiences with PBSC collections for patients with SCD who were enrolled in a gene therapy clinical trial. This survey was distributed to 37 apheresis practitioners at large academic medical centers around the country with apheresis services. The survey queried demographics, RCE before PBSC collection, and PBSC collection. It incorporated narrative responses and postsurvey follow-up questions. Eight individuals from different centers responded (response rate, 21.6%). Although >15 institutions were conducting gene therapy studies by 2021, we suspect that most facilities at that time did not have the volume of SCD patient collections to engage with the survey. Only 6 of 8 (75%) respondents, indicated that their institution performed PBSC collections for patients with SCD. The results of the survey are summarized in Table 1.

Practice variability among participating collection sites

| Survey queries and responses (N = 6) . | No. of responses (%) . |

|---|---|

| Patient age group | |

| Adults | 1 (16.7%) |

| Pediatrics | 1 (16.7%) |

| Adult and pediatrics | 4 (67%) |

| Pediatric patient age range | |

| 0-18 y | 2 (33.3%) |

| 0-21 y | 1 (16.7%) |

| 0-35 y | 1 (16.7%) |

| No response | 2 (33.3%) |

| Pre-collection RBC transfusion type | |

| Manual whole blood exchange | 1 (16.7%) |

| Simple RBC transfusion | 4 (66.7%) |

| Automated RCE | 6 (100%) |

| Pre-collection transfusion number of sessions | |

| Manual whole blood exchange | |

| 2 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| Simple RBC transfusion | |

| 0-1 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2-3 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 6 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| Automated RCE | |

| 1 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2-3 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 sessions | 2 (33.3%) |

| 3-5 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| Precollection RBC transfusion frequency | |

| 3 wk | 1 (16.7%) |

| 4 wk | 5 (83%) |

| Last precollection RBC transfusion prior to PBSC collection (d) | |

| 1 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 1-3 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 6 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 10 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Posttransfusion HbS percentage | |

| 5-15% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 15% | 2 (33.3%) |

| 22% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 30% | 2 (33.3%) |

| Apheresis collection instrument | |

| Spectra Optia | 6 (100%) |

| Fenwal Amicus | 0 |

| Spectra Optia protocol | |

| cMNC | 3 (50%) |

| MNC | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (33.3%) |

| Total blood volumes processed per procedure | |

| 4 total blood volumes | 3 (50%) |

| No answer | 3 (50%) |

| Plerixafor administration prior to collection (h) | |

| 2 h | 2 (33.3%) |

| 2-3 h | 1 (16.7%) |

| 4 h | 3 (50%) |

| Precollection peripheral blood CD34+ cell count on day 1 (CD34+ cells/μL) | |

| 0.2 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 25 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 30 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 35 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 41 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Anticoagulant: whole blood ratio | |

| 1:13 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 1:12 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 1:10 | 2 (33.3%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| Target color of the collect line | |

| Second lightest color | 1 (16.7%) |

| Second darkest color | 1 (16.7%) |

| Between the 2 darkest colors | 3 (50%) |

| No response | 1 (16.7%) |

| Collection efficiency (CE2 formula) | |

| 35 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 43 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 45 | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (33.3%) |

| Number of collection cycles | |

| 1 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 2 | 3 (50%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| CD34+ cells/kg yield per day | |

| 1 x 106 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 x 106 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 4 x 106 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 6.46 x 106 | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| Product TNC count | |

| 3 x 109 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 4 x 109 | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 4 (66.7%) |

| CD34+ cell viability (%) | |

| 97% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 99% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 99-100% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 100% | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (50%) |

| Product hematocrit (%) | |

| 2% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 7% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 5-8% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 12% | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (33.3%) |

| TBV to process | |

| Fixed TBV | 2 (33.3%) |

| Fixed TBV or liters of whole blood | 1 (16.7%) |

| Fixed time | 2 (33.3%) |

| Prediction algorithm | 1 (16.7%) |

| Criteria to proceed with PBSC collection | |

| No | 4 (66.7%) |

| Yes | |

| Minimum peripheral blood CD34+ cell count | 1 (16.7%) |

| 10 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Collection parameter altered | |

| Collection preference | 4 (80%) |

| Increasing collection days | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| Survey queries and responses (N = 6) . | No. of responses (%) . |

|---|---|

| Patient age group | |

| Adults | 1 (16.7%) |

| Pediatrics | 1 (16.7%) |

| Adult and pediatrics | 4 (67%) |

| Pediatric patient age range | |

| 0-18 y | 2 (33.3%) |

| 0-21 y | 1 (16.7%) |

| 0-35 y | 1 (16.7%) |

| No response | 2 (33.3%) |

| Pre-collection RBC transfusion type | |

| Manual whole blood exchange | 1 (16.7%) |

| Simple RBC transfusion | 4 (66.7%) |

| Automated RCE | 6 (100%) |

| Pre-collection transfusion number of sessions | |

| Manual whole blood exchange | |

| 2 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| Simple RBC transfusion | |

| 0-1 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2-3 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 6 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| Automated RCE | |

| 1 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2-3 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 sessions | 2 (33.3%) |

| 3-5 sessions | 1 (16.7%) |

| Precollection RBC transfusion frequency | |

| 3 wk | 1 (16.7%) |

| 4 wk | 5 (83%) |

| Last precollection RBC transfusion prior to PBSC collection (d) | |

| 1 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 1-3 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 6 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 10 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Posttransfusion HbS percentage | |

| 5-15% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 15% | 2 (33.3%) |

| 22% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 30% | 2 (33.3%) |

| Apheresis collection instrument | |

| Spectra Optia | 6 (100%) |

| Fenwal Amicus | 0 |

| Spectra Optia protocol | |

| cMNC | 3 (50%) |

| MNC | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (33.3%) |

| Total blood volumes processed per procedure | |

| 4 total blood volumes | 3 (50%) |

| No answer | 3 (50%) |

| Plerixafor administration prior to collection (h) | |

| 2 h | 2 (33.3%) |

| 2-3 h | 1 (16.7%) |

| 4 h | 3 (50%) |

| Precollection peripheral blood CD34+ cell count on day 1 (CD34+ cells/μL) | |

| 0.2 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 25 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 30 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 35 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 41 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Anticoagulant: whole blood ratio | |

| 1:13 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 1:12 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 1:10 | 2 (33.3%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| Target color of the collect line | |

| Second lightest color | 1 (16.7%) |

| Second darkest color | 1 (16.7%) |

| Between the 2 darkest colors | 3 (50%) |

| No response | 1 (16.7%) |

| Collection efficiency (CE2 formula) | |

| 35 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 43 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 45 | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (33.3%) |

| Number of collection cycles | |

| 1 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 2 | 3 (50%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| CD34+ cells/kg yield per day | |

| 1 x 106 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 3 x 106 | 2 (33.3%) |

| 4 x 106 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 6.46 x 106 | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

| Product TNC count | |

| 3 x 109 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 4 x 109 | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 4 (66.7%) |

| CD34+ cell viability (%) | |

| 97% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 99% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 99-100% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 100% | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (50%) |

| Product hematocrit (%) | |

| 2% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 7% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 5-8% | 1 (16.7%) |

| 12% | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 2 (33.3%) |

| TBV to process | |

| Fixed TBV | 2 (33.3%) |

| Fixed TBV or liters of whole blood | 1 (16.7%) |

| Fixed time | 2 (33.3%) |

| Prediction algorithm | 1 (16.7%) |

| Criteria to proceed with PBSC collection | |

| No | 4 (66.7%) |

| Yes | |

| Minimum peripheral blood CD34+ cell count | 1 (16.7%) |

| 10 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Collection parameter altered | |

| Collection preference | 4 (80%) |

| Increasing collection days | 1 (16.7%) |

| No answer | 1 (16.7%) |

cMNC, continuous mononuclear cell; MNC, mononuclear cell; SD, standard deviation; TBV, total blood volume; TNC, total nucleated cells.

Respondents faced a number of challenges while preparing for, and performing, PBSC collections in patients with SCD compared with other patient populations, including limited mobilization leading to a low starting CD34+ cell count and more collection days to achieve the goal, clotting of vascular access, difficulty achieving the target HbS before collection, obtaining RBC units for patients with high rates of alloimmunization, instability of the apheresis mononuclear cell collection interface, unpredictable nature of the collection with some patients who mobilize well collecting poorly, patient comfort and pain control.

A wide variation in practice standards surrounding apheresis for SCD emerged from the survey results; particularly, the collection techniques surrounding HSC collection. Given that relatively few patients had been treated with gene therapy at the time of survey distribution, it is not surprising that many of the critical factors for a successful collection remain unsolved. The lack of protocols surrounding the collection and pretransplant activities is also apparent in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labels for the 2 commercial drug products. Transfusion and apheresis parameters are not specified, and many treatment targets and protocols are left up to individual prescribers to decide. Understanding the impact of these parameters is a pressing issue because the ability to enter patients into gene therapy programs is critical to having an impact. The tools and metrics for the collections as depicted in the survey need wider study and communication.

Premobilization transfusion therapy

Transfusion has been long used to treat anemia in SCD and has been shown to prevent VOEs including stroke in select patients.19,20 A major intent of RBC transfusions is to offer added protection from VOEs, because patients are expected to discontinue other disease-modifying drugs such as hydroxyurea as they prepare for PBSC collection and subsequent transplantation.21 Additional theoretical benefits to preparative RBC transfusion include alleviation of stress erythropoiesis, thereby improving reticulocytosis and hemolysis, reduction of free heme to improve immune function and inflammation,22 and decreasing inflammatory effects resulting from the vasculopathy of SCD. Studies in mouse models of SCD have shown the BM to have altered distribution of vasculature, decreased number of HSCs, and decreased mesenchymal stem cell frequency and function, with a striking normalization after just 4 to 6 weeks of RBC transfusions.23,24 Furthermore, patient characteristics and disease severity also influence collection outcomes, and having a RBC transfusion preparative regimen may help modulate these characteristics.25,26

In most protocols, transfusion is started at variable time points before mobilization, ranging from 6 to 12 weeks, using simple transfusion or RCE. Transfusion during this period is commonly managed to maintain HbS of <30%, a functionally derived target from stroke prevention trials.27,28 A low HbS percentage of 10% to 20% is typically targeted for each RCE, with an interval of 4 weeks between RCE to preemptively achieve a HbS of <30% at all times. Whether HbS targets this low are necessary before collection warrants further investigation. The optimal Hb and hematocrit (HCT) targets also remain undefined, although most collection centers aim for a Hb between 8 g/dL and 10 g/dL (∼24%-30% HCT) to mitigate iron overload, potential RBC alloimmunization, and hyperviscosity. Lastly, the optimal duration of premobilization transfusion therapy is unknown and further study is required to identify specific transfusion goals associated with improved collection outcomes. Those with brisk erythropoietic drives and active vasculopathy may benefit from a longer transfusion period before mobilization and collection; however, this is an area of intense investigation.

Although transfusions are beneficial for optimizing the physiology of patients with SCD before a PBSC collection, prolonged therapy increases the risk of RBC alloimmunization, which would complicate the transfusion regimen.29 This consideration is especially important when embarking on a prolonged transfusion period before mobilization and transplant in which ≥4 RCEs using dozens of units of RBCs are required. A thorough evaluation by transfusion medicine specialists is imperative before study entry for these patients to assess transfusion feasibility; the presence of rare RBC antigen phenotypes; and the potential need for iron chelation to tailor the modality, frequency, intensity, and duration of transfusion to each patient. RBC donors have to be selected carefully, and transfusion events have to be meticulously planned. Because many patients may be referred for curative therapies from another institution, it is important to obtain a complete history of previous alloimmunization and transfusion reactions from the blood bank(s) of institutions at which the individual had received previous transfusions. RBC antigen genotyping including the RH loci (D, C/c and E/e, with attention to variants) should be considered for all patients early on and ideally before the first transfusion.30 Having the RBC antigen profile readily available will help with RBC unit selection and the prevention of further alloimmunization in patients with significant alloimmunization.30 For patients with Rh alloimmunization, assessing for genotype-based donor selection may avoid hemolytic reactions. At minimum, RBCs should be C/c-, E/e-, and K-matched and, if the patient has significant alloimmunization or has a history of delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions or hyperhemolysis, extended matching (Duffy, Kidd, S) should be provided. Overcoming barriers to transfusion associated with alloimmunization and hemolytic reactions is of paramount importance to increase access of patients to these therapies.

A major complication of RBC transfusions is iron overload. Each unit of packed RBCs contains ∼200 mg of iron. Chronic or intermittent simple RBC transfusions of 10 to 20 cumulative RBC units can lead to the accumulation of iron in the body. RCE is generally preferred over simple RBC transfusions due to its ability to replace HbS-containing RBCs with healthy donor RBCs with minimal effects on blood viscosity, fluid balance, and iron burden.31 However, when RCE procedures are frequently performed with an increase in end-procedure HCT, iron overload could also occur. Free iron accumulates in various organs of the body including the liver, heart, and endocrine system, which leads to organ dysfunction. Iron chelation therapy, such as with deferoxamine and deferasirox, will help maintain a negative or neutral iron balance to prevent hemosiderosis.32 Iron chelation therapy typically follows chronic transfusion after ∼10 to 20 cumulative RBC units have been transfused.33 The iron status of the patient should be assessed before the start of, and throughout, the process of gene therapy, and iron chelation initiated when appropriate.

Peripheral blood HSC mobilization

Over the past 30 years, PBSC mobilization has relied on G-CSF to enrich HSCs in the peripheral blood of healthy donors and patients with cancer.34 When G-CSF was used in patients with SCD undergoing PBSC collections as part of a cancer treatment plan, a relatively high number of VOEs and deaths were reported. Although preventative RCE has been used to avert these significant adverse events in some cases, G-CSF remains contraindicated for use in autologous collections for gene therapy in patients with SCD.35 Plerixafor has emerged as a safe and reliable mobilization agent for patients with SCD. It is a selective small molecule inhibitor of CXCR4 that binds to CXCR4 and blocks the binding of its ligand CXCL12, thus, releasing HSCs into the peripheral blood.

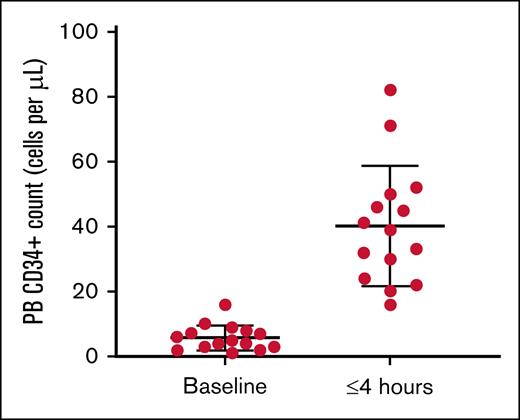

Plerixafor administration in patients with SCD has been used extensively as a sole agent for HSC collection.36-39 Many studies have shown that CD34+ cells are present as early as 3 to 4 hours after plerixafor administration in contrast to 6 to 12 hours in healthy adults.17 Detailed mobilization kinetic studies of plerixafor’s peak activity in patients with SCD have not been performed. Nevertheless, sufficient cells are present by 4 hours to warrant the recommendation that collection begin 3 to 4 hours after plerixafor administration for SCD40 (Figure 1).

PB CD34+ cells per μL in patients with SCD at baseline and up to 4 hours after mobilization with 240 μg/kg of plerixafor. Counts were obtained before apheresis collection. PB, peripheral blood.

PB CD34+ cells per μL in patients with SCD at baseline and up to 4 hours after mobilization with 240 μg/kg of plerixafor. Counts were obtained before apheresis collection. PB, peripheral blood.

Plerixafor dosing for SCD has largely been studied at 240 μg/kg. A limited study examined dose escalation to 480 μg/kg, with higher doses showing a potential trend for enhanced mobilization with no adverse events.41 Although plerixafor is approved at a dose of 240 μg/kg, there was a modification to the FDA label in 2011 to allow a fixed single dose of 20 mg for patients with body weights of <83 kg, and at 240 μg/kg for patients with body weights of >83 kg, with a maximum dose of 40 mg. This decision was based on evidence that the distribution of the drug was different in patients with lower body weights, raising the point that patients with lower body weights, especially children, may be underdosed if limited to 240 μg/kg. Fixed dosing as indicated by the FDA label indication can be considered in adults undergoing mobilization and further investigation can help guide dosage adjustments in children.

Additional PBSC mobilization agents are needed, and many are presently in clinical trials. Motixafortide is a CXCR4 antagonist with higher CXCR4 affinity than plerixafor.42 The VLA4-VCAM1 pathway is another important axis contributing to HSC lodgment to the BM. Natalizumab is an FDA-approved anti-VLA4 monoclonal antibody used to prevent inflammation in diseases such as multiple sclerosis, with observations of a twofold to threefold increase in PBSCs in patients taking this medication. Other VLA4 inhibition strategies (eg, the small molecule BIO5192) are also being investigated.43 An additional mechanistic axis that can be used for mobilization is the CXCR2 agonist Gro-β, which induces the release of neutrophil matrix metalloproteinase, thereby releasing HSCs from the BM. Mobilization efficacy of these agents in conjunction with plerixafor is being investigated.

PBSC collection by apheresis

One aspect of SCD PBSC collection that has received great attention is the technical parameters related to the apheresis procedure. Technical parameters that can be adjusted include the depth of collection within the mononuclear cell layer (the collection interface), the anticoagulant used and its ratio to whole blood, the anticoagulant rate, the inlet flow rate into the device of whole blood, and the collect flow rate (rate of collection into the product bag). Extremely low collection efficiency for many patients has led many to alter collection settings to improve outcomes. Despite adequate PBSC mobilization, in some patients <1 to 2 million CD34+ cells per kg are collected, which may be too low for successful manufacturing of a gene therapy product. The following factors have emerged as important variables in collections based on the collective personal experience of the CureSCi AWG members.

Operator competency

When evaluating the efficiency of cell collection, the training and experience of the operator are crucial factors. Inefficiencies in cell collection procedures often stem from an inability to manage procedural instrument alarms, failure to maintain a stable red and white blood cell interface (ie, the common boundary between the RBC and white blood cell layers in a PBSC collection procedure), and insufficient volume of blood processed.44 Skilled operators who can effectively overcome these challenges is essential for optimizing apheresis cell collections. These challenges are exacerbated by nursing shortages in the United States, which have affected apheresis centers nationally. To address this issue, data analysis to direct accelerated training and optimization programs should be used to decrease the time required for operators to achieve competency. The Spectra Optia Apheresis System (Terumo BCT, Lakewood, CO) is one of the most widely used instruments for collections nationally; apheresis instruments record data that can be leveraged to troubleshoot and optimize cell collection procedures, enhancing efficiency within individual collection units. Although there has been notable success with data analytics on a local level, the future goal is to aggregate data across multiple sites to achieve optimal collection efficiency on a larger scale. Future software solutions will also ease the burden of regulatory compliance documentation at collection sites.

Apheresis anticoagulation and collection preference (CP) parameters

Patients with SCD are prone to thrombotic events, with multiple factors contributing to this pathophysiology including endothelial injury and activated inflammatory cells resulting in a hypercoagulable state. To this end, microthrombi can be detected in apheresis circuits during RCE and particularly during PBSC collection. Citrate infusion has been widely used as an anticoagulant in the form of anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution A (ACDA) at a ratio of 1:12 to 1:14. In patients with SCD, operators often increase the ACDA-to–whole blood ratios to as high as 1:8.45 In addition to potential toxicity from calcium and magnesium depletion, the decreased flow rate may disrupt the collection port interface and thereby interfere with the collection efficiency. Heparin or solutions containing both ACDA and heparin, which may reduce microthrombi formed within the instrument and allow for improved flow dynamics through the collection ports, can be used if there are no downstream cell processing restrictions. Although the use of heparin in apheresis circuits has not been validated by all manufacturers, many centers participating in the AWG have completed successful collections with this strategy. Aspirin has been used by many centers and further study is needed to better understand its utility.

The collection of a buffy coat–containing PBSCs is based on the visual appearance of the color of the buffy coat in the collection line. This can be observed optically as a CP (range, 10-90), is guided by the operator, and based on the color of the interface collected. The CP is a fine control of the depth at which PBSCs are collected from within the buffy coat layer. In turn, the color of the interface is formed by the HCT, with the lightest to darkest color preference moving from platelets and lymphocytes (estimated HCT of <1%), to monocytes and HSCs (HCT of ∼3%), to granulocytes (HCT∼5%).46 PBSC collections from patients with normal RBC morphology usually occur at the midrange of the color preference (CP default of 50), with a HCT of 2% to 3%. To maintain the appropriate color, operators must pay close attention to the color of the collect line, because microthrombi in the collection circuit can lead to an unstable interface. Several reports and experience from operators found that a higher yield of HSCs can be generated from patients with SCD at the darker color preference (CP of ∼10; HCT of ∼5%). Collecting at the darker interface requires more training and is associated with an apheresis product containing more RBCs. Correspondingly, patients undergoing multiple days of collection may become anemic and require additional transfusion.

Transfusion and apheresis vascular access

Appropriate vascular access is critical to the successful collection of HSCs in any patient because continuous, uninterrupted flow contributes to a stable interface and allows an efficient collection. For individuals with SCD who may have increased risk of microthrombi or reticulocytes in the circuit, which can lead to an unstable interface, it is particularly important. Frequent instrument pausing due to pressure alarms related to poor vascular access can decrease the efficiency of collection, or in extreme cases, cause aborted procedures. In addition, adequate flow rates are necessary to allow processing enough blood volume to achieve collection targets and longer collection times/increased blood volume processing may be necessary to achieve collection goals in individuals with SCD who have relatively low precollection CD34+ cell counts.47

Peripheral IV (PIV) access may be possible for RCE procedures leading up to the collection but requires experienced nursing staff with training in establishing PIV access for apheresis in this patient population. In the authors’ clinical experience, developing a program incorporating ultrasound-guided PIV placement has increased the success of using peripheral access and avoiding central venous catheters (CVCs) for RCE. If peripheral access is not possible, a variety of methods for central access have been used, including implanted ports, temporary CVCs placed the day of the procedure, or arteriovenous fistulas or grafts. No one method of central access has proven ideal and depends on a combination of patient preference and the local resources/expertise available.

To optimize the chance of successful collection of PBSCs, which involve much longer procedures than RCE, conducted over multiple days, central access with an apheresis-compatible catheter has traditionally been required. Recently, the use of midline catheters has offered a promising alternative to CVCs for patients undergoing apheresis.48,49 Midline catheters are inserted through a deeper, larger peripheral vein, with the tip typically terminating in the axilla. Experience with midline catheters has been reported in small numbers of adult and pediatric apheresis populations, including RCE in SCD and PBSCs in patients without SCD. These reports have documented adequate flow rates and minimal adverse events and warrant further study, especially for feasibility in PBSC collections.

Limitations of cell manipulation and manufacturing

To obtain the required target cells for downstream processing, between 2 to 4 consecutive days of collection may be required. Cell manipulation protocols vary, and some apheresis products are stored in the laboratory overnight whereas others undergo cryopreservation before shipping to the manufacturer. Specific manufacturing approaches, limited days for manufacturing, and requirements for fresh or frozen cells can also influence the number of consecutive collection days that can safely take place. For all these reasons, it is not uncommon for patients entering SCD gene therapy to fail to meet cell-dose targets for gene therapy with the initial mobilization cycle. Repeat mobilization cycles can add 3 to 4 months to the time from study entry until manufacturing begins, with some patients requiring ≥3 collection cycles (Table 2). There can be weeks-long resting periods between collection cycles, with required chronic transfusion support between collection cycles. Multiple collections can also lead to multiple drug products, the collection for which should be linked through a chain of identity identifiers. Lastly, the additional expense and resources needed for many of the transfusion and monitoring procedures need to be considered when considering offering gene therapy as an institution and for a particular patient. It is important to set timelines and realistic expectations with providers and patients when starting the transfusion preparative regimens.

Apheresis parameters of published trials for SCD gene therapy

| Trial . | Patients (reported) . | Premobilization transfusion . | Apheresis cycles . | Apheresis starting material cell target (CD34+ cells per kilogram) . | Gene therapy product cell dose target (CD34+ cells per kilogram) . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lovotibeglogene autotemcel (bluebird)12 | 15 | 60 days | 8 patients, 1 cycle 6 patients, 2 cycles 1 patient, 3 cycles 1.7 apheresis/patient (2 d/cycle) | 15 × 106 | 3 × 106 | Cell products shipped fresh |

| Exagamglogene autotemcel (Vertex)13 | 44 | 8 weeks | Median 2 per cycles 32% of patients ≥3 cycles of 2 days per cycle | 15 × 106 | 3.5 × 106 | Cell products shipped fresh |

| OTQ923 Novartis50 | 3 | 60 days | Three patients with 3, 2, and 2 cycles, respectively, of 2-3 days per patient | 15 × 106 | 2 × 106 | Cryopreserved, 2/3 patients met cell dose target |

| BCH-BB694 (BCH/NHLBI)14 | 6 | 12 weeks | 1 cycle of up to 2 apheresis days | 15 × 106 | 4 × 106 | Cell products shipped fresh |

| Trial . | Patients (reported) . | Premobilization transfusion . | Apheresis cycles . | Apheresis starting material cell target (CD34+ cells per kilogram) . | Gene therapy product cell dose target (CD34+ cells per kilogram) . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lovotibeglogene autotemcel (bluebird)12 | 15 | 60 days | 8 patients, 1 cycle 6 patients, 2 cycles 1 patient, 3 cycles 1.7 apheresis/patient (2 d/cycle) | 15 × 106 | 3 × 106 | Cell products shipped fresh |

| Exagamglogene autotemcel (Vertex)13 | 44 | 8 weeks | Median 2 per cycles 32% of patients ≥3 cycles of 2 days per cycle | 15 × 106 | 3.5 × 106 | Cell products shipped fresh |

| OTQ923 Novartis50 | 3 | 60 days | Three patients with 3, 2, and 2 cycles, respectively, of 2-3 days per patient | 15 × 106 | 2 × 106 | Cryopreserved, 2/3 patients met cell dose target |

| BCH-BB694 (BCH/NHLBI)14 | 6 | 12 weeks | 1 cycle of up to 2 apheresis days | 15 × 106 | 4 × 106 | Cell products shipped fresh |

NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Adverse events related to mobilization and collection

Overall, there are relatively few adverse events associated with apheresis collections and mobilization. Many of the adverse events are associated with insertion or the prolonged use of indwelling catheters. Apheresis grade catheters and indwelling apheresis ports are associated with a high rate of thrombotic events.51 In some studies, up to a third of patients with catheters experience a thrombotic event, raising the question about the use of prophylactic anticoagulation for some patients. Patients at greater risk are those with a history of thrombosis, and female patients that may be undergoing hormonal manipulation in preparation for fertility preservation related to the gene therapy.

On the day of collection, VOEs have been reported despite the preemptive RCE. Timing of collection and advance preparation and education of patients with frequent pain is key to controlling these events. Pain may be elicited by the stress of multiple days of sequential apheresis collections, fluid shifts, citrate toxicity, and extended collection procedures lasting up to 8 hours.52 Adequate hydration and pain medications for symptomatic control of pain are typically necessary to allow the patient to complete the collection cycles.

Plerixafor administration to patients with SCD is generally safe, with adverse events similar to those seen in healthy patients, such as gastrointestinal disturbance and headache.17 Most collections have taken place in the inpatient setting due to the logistics of timing vascular access, plerixafor administration, and prolonged collections. However, given the safety of plerixafor and the ability to identify patients at risk for VOE, select patients may undergo collection as an outpatient, especially if mobilization and collection are optimized. Special attention should be given to fluid balance, because the increased citrate and calcium or magnesium replacement during collection may lead to fluid overload. Outpatient apheresis at centers with expertise in SCD would potentially allow easier scheduling given the inherent constraints with inpatient admissions.

Conclusion

The recent approvals of gene therapies for SCD are a remarkable achievement but they depend on the ability to efficiently collect HSCs. Understanding the role of transfusion in modulating the BM and mobilization is critical in helping to define the preparative regimen for gene therapy. Improved collection techniques with the development of tools and metrics to track success are necessary to overcome the current impediment of multiple collections and collection cycles. The efficiency of collection and cell manufacture in previous trials (Table 2) is currently evolving and requires adjustments to improve outcomes. With the commercialization of gene therapy products, scaling up production will at least require improved efficiency of collection. Educating health care providers and patients on the variables affecting starting material quantity and quality will be important to improve the efficacy, cost, and accessibility of current SCD gene therapies.

The experience gained in the past decade, from basic investigation, to clinical trials, to drug approval, has underscored the extraordinary burden to coordinate transfusion, collection, and transplant that were not foreseen. Improving each of the preparative steps will allow for wider participation of patients in therapies and better outcomes for patients. One of the most important recommendations formed by our working group is the need for improved communication amongst the multidisciplinary providers in a timely manner. The specific preparative regimen for HSC mobilization including transfusion and vascular access is not a standardized practice and requires careful planning to efficiently and safely navigate the 6-to-9-month period between confirming eligibility and transplant. For this reason, it is critical to involve transfusion medicine specialists early to help assess each patient’s unique transfusion needs, set appropriate parameters and frequency for RCE, and ensure proper apheresis technical settings to assure a successful collection. Careful documentation of the assessment and plan can serve as a common source of information regarding the preparative regimen and stem cell collection. Finally, patients also require education about the expectations for the length of time of the preparative regimen and its impact on work and quality of life to improve their overall experience. This is a highly evolving field, and transparent communication of collection outcomes from commercial cell manufacturers can help better set patient and provider expectations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative leadership in establishing the Apheresis Working Group and their commitment to advancing safe and effective transfusion therapies for sickle cell disease. The authors thank Lis Welniak, Traci Mondoro, and Juan Salomon from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and Nicole Ritzau and staff from the Emmes Company for their guidance, organizational support, and editorial assistance in support of the working group’s efforts.

This research was, in part, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) agreement OT2HL142340 (Emmes), OT2HL152800 (J.P.M.), P01HL158688 (J.P.M.), U01 HL169401 (S.C.), and R01 HL134696 (S.C.).

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.C.T. conceptualized the manuscript, designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.T. conceptualized and revised the manuscript; P.S. and S.C. reviewed and revised the manuscript; S.A.K. conceptualized the manuscript, designed and performed the research, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; G.F.M. and C.N. reviewed and revised the manuscript; K.W., Y.Z., C.F., and C.A. conceptualized the manuscript; K.C. performed research; V.C.-C. and A.S. conceptualized the manuscript; and J.P.M. conceptualized the manuscript, designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.T. is a member of the board of directors of the Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies. J.P.M. has been a speaker with Terumo BCT and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. C.N. is an employee at Terumo BCT. C.F. was an employee of CRISPR Therapeutics, and Novartis; and is currently a cell and gene therapy (CGT) consultant. C.A. was an employee of bluebird bio, CRISPR Therapeutics, and AVROBIO; an independent CGT consultant; and is currently an employee of Circulate. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yvette C. Tanhehco, Division of Transfusion Medicine, Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, 622 W 168th St, Harkness Pavilion 4-418A, New York, NY 10032; email: yct2103@cumc.columbia.edu; and John P Manis, Joint Program in Transfusion Medicine, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, 320 Longwood Ave, Mailstop BCH3105, Enders Research Laboratories 809, Boston, MA 02115; email: john.manis@childrens.harvard.edu.