Key Points

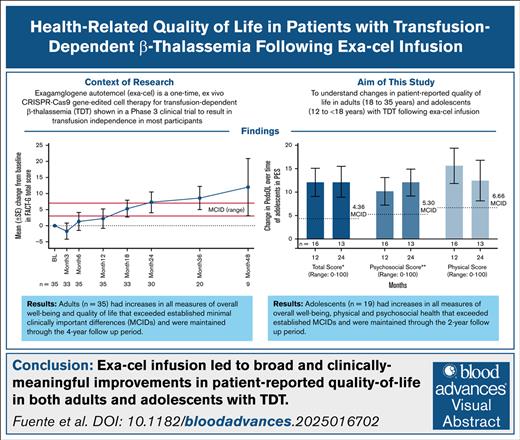

Exa-cel improved overall HRQoL in patients with TDT.

Clinically meaningful improvements in HRQoL were seen in both adults and adolescents and across a wide range of health domains.

Visual Abstract

Transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT) can have negative impacts on a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Exagamglogene autotemcel (exa-cel) is a one-time, ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 gene–edited cell therapy for TDT shown in a phase 3 clinical trial to result in transfusion independence in most participants. Here, we describe changes in patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures after exa-cel infusion in 54 participants (adults, n = 35; adolescents, n = 19), who had ≥16 months of follow-up. In adults, PRO measures included the EuroQol Quality of Life Scale-5 dimensions-5 levels of severity (EQ-5D-5L) and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT). In adolescents, the EuroQol Quality of Life Scale-5 dimensions-youth (EQ-5D-Y) and Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) instruments were used. At baseline, mean EQ-5D-5L visual analog scale (VAS) and US and UK health utility index scores in adults were in line with baseline scores reported for adults with TDT. After exa-cel infusion, all 3 scores improved, exceeding established minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) at month 48. Mean FACT-General (FACT-G) score and bone marrow transplant subscale score improved through month 48, also exceeding MCIDs, with improvements in all 4 FACT-G subscales (physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being). Consistent with HRQoL improvements in adults, adolescents had increases from baseline at month 24 in mean EQ-5D-Y VAS score and PedsQL total score, with sustained improvements in both physical and psychosocial health subcomponents. These results indicate exa-cel leads to broad, durable, and clinically meaningful improvements in HRQoL in adults and adolescents with TDT. These trials were registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03655678 and #NCT04208529.

Introduction

β-Thalassemia is an inherited erythroid disorder resulting from mutations in the β-globin gene, which lead to a reduction in the production of β-chains in adult hemoglobin (Hb; namely, HbA).1,2 Clinically, these molecular changes manifest in ineffective erythropoiesis and chronic anemia. Patients with β-thalassemia are often classified based on their need for red blood cell (RBC) transfusions to manage the disease; those who are dependent on regular RBC transfusions throughout their lives to maintain recommended Hb levels are classified as having transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT).3,4 Patients with TDT experience progressive and debilitating complications5 and require regular iron chelation therapy (ICT) to mitigate toxicities associated with RBC transfusion–related iron overload.6 Despite the availability of safe blood products and the use of regular ICT, patients frequently develop clinical complications associated with TDT, which include heart failure, liver disease, endocrinopathies, immune system disorders, and arthropathy.1,2 Further complicating treatment of patients with TDT are challenges associated with adherence due to side effects and the demands of time-consuming treatment regimens.6-10 As a result, TDT and its clinical management have been shown to lead to substantial impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL).7,8,11-13

Aside from regular RBC transfusions and ICT, traditionally there have been few other treatment options available to patients with TDT. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative option for patients with TDT; however, its use has been limited by donor availability, and the risk of transplant-related complications which increases with patient’s age.14,15 Recently, a novel therapy known as exagamglogene autotemcel (exa-cel) was approved for use in patients with TDT. Exa-cel is a cell therapy designed to reactivate the synthesis of fetal Hb (HbF) via nonviral, ex vivo CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing of autologous CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) at the erythroid-specific enhancer region of BCL11A.16 Previous natural history studies showed that elevated levels of HbF, such as those of the condition known as hereditary persistence of HbF, are associated with reduced morbidity and mortality in patients with TDT.17-19

In a prespecified interim analysis of the pivotal phase 3 CLIMB THAL-111 trial, a single infusion of exa-cel increased mean HbF levels to 11.9 g/dL, eliminating the need for RBC transfusions in 91% of participants with TDT, the primary end point of the study, with a safety profile consistent with the myeloablative, busulfan-based conditioning regimen and autologous HSCT.20 These results, which were consistent among adolescents and adults, demonstrated the potential for exa-cel to provide a one-time functional cure to patients with TDT. Participants who completed CLIMB THAL-111 were offered the opportunity to enroll into an extension study (CLIMB-131) for a total of 15 years of follow-up after exa-cel infusion.

A secondary objective of the CLIMB THAL-111 and CLIMB-131 trials is to assess the impact of exa-cel on patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. PRO measures, which evaluate HRQoL, provide important information on a patient’s physical, social, and emotional functioning, as well as additional insight into the impact of treatment on the patient experience.21 In the previously reported prespecified interim analysis of CLIMB THAL-111, adults with at least 16 months of follow-up after exa-cel infusion had robust improvements in PRO measures at month 24, indicative of improved quality of life.20 Here, we report changes in PRO measures for up to 48 months in adults and up to 24 months in adolescents after receiving exa-cel in the pivotal CLIMB THAL-111 phase 3 clinical trial and the long-term extension study CLIMB-131.

Methods

Study design and patients

CLIMB THAL-111 is an ongoing, 24-month, phase 3 clinical trial of a single dose of exa-cel in patients aged 12 to 35 years, who have TDT along with a history of ≥100 mL/kg per year or ≥10 units per year of packed RBC transfusions for the 2 years before screening. Participants received a combination of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and plerixafor for HSPC mobilization followed by apheresis to collect CD34+ HSPCs for ex vivo gene editing. Before infusion, all participants received myeloablative conditioning with pharmacokinetically adjusted busulfan. Exa-cel was administered IV at least 48 hours, but no more than 7 days, after conditioning. For additional details on the exa-cel infusion procedure, refer to Locatelli et al.20 Participants who complete the 2-year study period in CLIMB THAL-111 are offered the opportunity to enroll in a 13-year extension study, CLIMB-131.

The primary end point of the CLIMB THAL-111 trial is transfusion independence, defined as participants achieving a weighted average total Hb of ≥9 g/dL, without the need for RBC transfusion for a period of ≥12 consecutive months. The key secondary end point of the trial is participants achieving a weighted average total Hb of ≥9 g/dL without the need for RBC transfusion for a period of ≥6 consecutive months. Other secondary end points in the trial included assessments of total Hb and HbF concentrations, duration of transfusion independence, and changes from baseline in HRQoL based on adult and adolescent PRO measures.

The CLIMB THAL-111 and CLIMB-131 clinical trials were designed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and CRISPR Therapeutics in collaboration with the steering committee. Each participant or legal guardian provided written informed consent, and an independent data monitoring committee monitored safety. The study protocols were approved by the institutional review board at each participating institution. Data collection and analyses were conducted by Vertex Pharmaceuticals in collaboration with the authors. Trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, local applicable laws and regulations, and current Good Clinical Practice Guidelines described by the International Council for Harmonisation.

Data collection and patient-reported QoL assessments

PRO measures assessed in the CLIMB THAL-111 and CLIMB-131 trials include the validated generic and disease-specific measures EuroQol Quality of Life Scale-5 dimensions-5 levels of severity (EQ-5D-5L, including descriptive system and visual analog scale [VAS]) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT; including FACT-General [FACT-G] and bone marrow transplant subscale [BMTS]) for adults and the EuroQol Quality of Life Scale-5 dimensions-youth (EQ-5D-Y) and Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) for adolescents. A description of PRO measures is provided in supplemental Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of PRO measurements used descriptive statistics (eg, mean, standard error, and standard deviation) and no hypothesis testing was performed at any stage after collection of these data. All plots used mean and standard error to show precision of sample mean; mean and standard deviations for all plot time points provided in online supplement. Change from baseline, defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (namely, latest time point with a valid measurement that was not considered null) obtained before the start of HSPC mobilization before exa-cel infusion, for the summary and domain scores from all assessed PRO measurements for each post baseline time point were determined based on available data at the time of analysis. To determine minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) for PRO measures, literature searches were conducted. MCIDs were identified based on scientific literature using both anchor- and distribution-based methods.22 MCIDs were estimated to be 7 to 10 points for EQ-5D-5L VAS and 0.078 and 0.08 points for US and UK index scores, respectively23,24; 3 to 7 points for FACT-G21; 2 to 3 points for BMTS25; PedsQL domain score MCIDs ranged from 4.36 to 9.12 points.26 Planned data cuts are conducted throughout both trials to allow for study review by the independent data monitoring committee.

Results

Participant demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

As of August 2024, 56 patients with TDT received exa-cel in the CLIMB THAL-111 trial. Of these patients, 54 had at least 16 months of follow-up (defined hereafter as the primary efficacy set) and were therefore included in analyses of PRO measures at the time of the data cut (Table 1). Before exa-cel infusion, all patients were dependent on RBC transfusions, with a mean historical number of RBC transfusion units per year in the 2-years period before screening of 36.6 units, indicative of severe TDT disease. Thirty-five patients in the primary efficacy set were adults (≥18 years of age) and 19 were adolescents (≥12 and <18 years of age), all of whom were included in analyses of PROs (Table 1).

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of participants in the primary efficacy set

| . | Primary efficacy set N = 54 . |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 29 (53.7) |

| Female | 25 (46.3) |

| Genotype, n (%) | |

| β0/β0 and β0/β0-like (β0/IVS-I-110; IVS-I-110/IVS-I-110) | 33 (61.1) |

| Non–β0/β0-like | 21 (38.9) |

| Age at screening, mean (standard deviation), y | 21.3 (6.6) |

| ≥12 and <18, n (%) | 19 (35.2) |

| ≥18 and ≤35, n (%) | 35 (64.8) |

| Historical RBC transfusions per year,∗ mean (range), units | 36.6 (11.0-71.0) |

| No. of mobilization cycles, median (range) | 1.0 (1.0-4.0) |

| Duration of follow-up after exa-cel infusion, median (range), mo | 38.4 (18.1-67.1) |

| . | Primary efficacy set N = 54 . |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 29 (53.7) |

| Female | 25 (46.3) |

| Genotype, n (%) | |

| β0/β0 and β0/β0-like (β0/IVS-I-110; IVS-I-110/IVS-I-110) | 33 (61.1) |

| Non–β0/β0-like | 21 (38.9) |

| Age at screening, mean (standard deviation), y | 21.3 (6.6) |

| ≥12 and <18, n (%) | 19 (35.2) |

| ≥18 and ≤35, n (%) | 35 (64.8) |

| Historical RBC transfusions per year,∗ mean (range), units | 36.6 (11.0-71.0) |

| No. of mobilization cycles, median (range) | 1.0 (1.0-4.0) |

| Duration of follow-up after exa-cel infusion, median (range), mo | 38.4 (18.1-67.1) |

Primary efficacy set was defined as participants who had at least 16 months of follow-up at the time of the data cut (August 2024).

Annualized over the 2 years before signing of informed consent or screening for participants who underwent rescreening in CLIMB THAL-111.

At time of the data cut, the median duration of follow-up was 38.4 months; for analysis of PRO measures, we report data for up to 48 months for adults and up to 24 months for adolescents (includes both CLIMB THAL-111 and CLIMB-131). A total of 47 of the 54 patients in the primary efficacy set completed the CLIMB THAL-111 trial and enrolled in the CLIMB-131 long-term extension study.

PRO assessments of HRQoL in adults in primary efficacy set

For adults, the mean baseline EQ-5D-5L VAS score, as well as baseline EQ-5D-5L health utility US and UK index scores, which are measures of overall health status, were near general population norms and in line with baseline scores previously reported for adults with TDT (Table 2). After exa-cel infusion, a substantial improvement in EQ-5D-5L VAS score, exceeding the MCID of 7 to 10 points, was observed by month 9 (mean change from baseline, 7.4 points [standard deviation (SD), 13.7]; n = 34), which was maintained through month 48 (mean change from baseline at month 48 was 14.0 points [SD, 25.4]; n = 9; Table 2). Improvements in mean EQ-5D-5L US and UK health utility index scores were also seen by month 9 and maintained through month 48, with a mean change from baseline greater than MCID at month 48 (Table 2).

Change from baseline in EQ-5D-5L scores in adults in the primary efficacy set after exa-cel infusion

| Visit . | Statistic . | EQ VAS . | US health utility index score . | UK health utility index score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Mean (SD) | 82.2 (16.0) | 0.89 (0.16) | 0.90 (0.13) | |

| Change at month 9 | n | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (13.7) | 0.01 (0.22) | 0.01 (0.17) | |

| Change at month 12 | n | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.7 (15.4) | 0.01 (0.23) | 0.01 (0.19) | |

| Change at month 24 | n | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (16.6) | 0.03 (0.25) | 0.02 (0.19) | |

| Change at month 48 | n | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.0 (25.4) | 0.19 (0.30) | 0.14 (0.25) | |

| Population norm | 80.4 (United States) 82.8 (United Kingdom) | 0.85 | 0.86 | |

| MCID | 7-10 | 0.078 | 0.08 |

| Visit . | Statistic . | EQ VAS . | US health utility index score . | UK health utility index score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Mean (SD) | 82.2 (16.0) | 0.89 (0.16) | 0.90 (0.13) | |

| Change at month 9 | n | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (13.7) | 0.01 (0.22) | 0.01 (0.17) | |

| Change at month 12 | n | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.7 (15.4) | 0.01 (0.23) | 0.01 (0.19) | |

| Change at month 24 | n | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (16.6) | 0.03 (0.25) | 0.02 (0.19) | |

| Change at month 48 | n | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.0 (25.4) | 0.19 (0.30) | 0.14 (0.25) | |

| Population norm | 80.4 (United States) 82.8 (United Kingdom) | 0.85 | 0.86 | |

| MCID | 7-10 | 0.078 | 0.08 |

Baseline is defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (scheduled or unscheduled) collected before the start of mobilization.

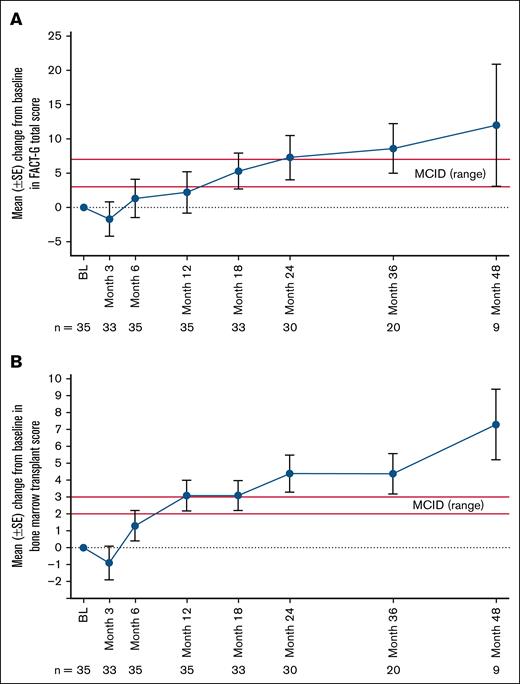

Mean FACT-G total score, a measure of general well-being and quality of life, similarly showed a substantial improvement by month 9 (mean change from baseline, 3.3 points [SD, 14.5]; n = 34) exceeding the MCID (3 to 7 points) and was generally sustained through month 48 (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 2A; supplemental Table 2). Notably, improvements exceeding MCIDs were observed in all 4 FACT-G subscales (physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being) at month 48 (supplemental Table 3). Specific improvements in fatigue were also noted in these PRO measures, with fewer adults reporting that they lacked energy after exa-cel infusion (supplemental Figure 1A). Consistent with findings from FACT-G measures of general well-being, changes in BMTS score, a measure of transplant-related well-being, also reached the established MCID (2 to 3 points) by month 9 (mean change from baseline, 2.1 points [SD, 5.2]; n = 34), with sustained improvements seen through month 48 (mean change from baseline at month 48, 7.3 points [SD, 6.2]); n = 9; Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 2B; supplemental Table 2).

Changes in FACT-G total and BMTS scores in adults in the primary efficacy set (PES) after exa-cel infusion. (A) Mean change from BL by study visit in FACT-G total score. (B) Mean change from BL by study visit in BMTS score. Red lines in figures depict established MCID range. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. BL is defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (scheduled or unscheduled) collected before the start of mobilization. BL, baseline; SE, standard error.

Changes in FACT-G total and BMTS scores in adults in the primary efficacy set (PES) after exa-cel infusion. (A) Mean change from BL by study visit in FACT-G total score. (B) Mean change from BL by study visit in BMTS score. Red lines in figures depict established MCID range. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. BL is defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (scheduled or unscheduled) collected before the start of mobilization. BL, baseline; SE, standard error.

PRO assessments of HRQoL in adolescents in primary efficacy set

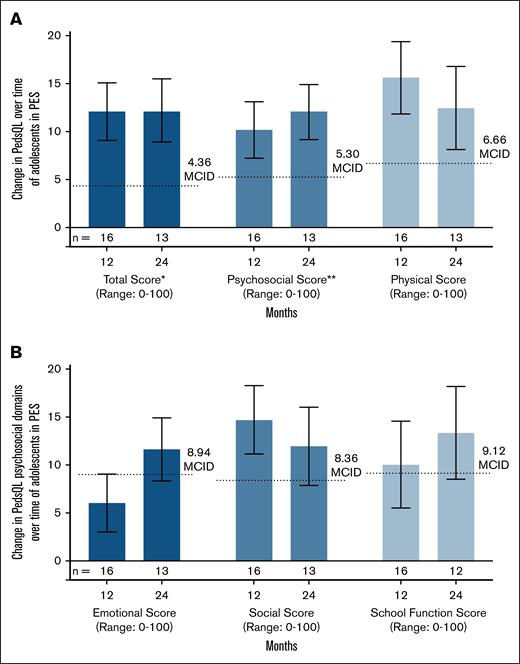

For adolescents (n = 19), mean EQ-5D-Y VAS score, a measure of overall health status, improved from baseline by month 6 after exa-cel infusion (mean change, 4.5 points [SD, 14.5]; n = 19), and was then generally maintained through the duration of the 24-month follow-up (mean change at month 24, 6.1 [SD, 16.4]; n = 15; Table 3). Mean PedsQL total score, which measures HRQoL in pediatric participants with chronic health conditions, also showed improvement by month 6 (mean change at month 6, 10.7 points [SD, 13.6]; n = 17), which was sustained through month 24 (mean change at month 24, 12.2 [SD, 11.8]; n = 13) and exceeded the established MCID (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3A; supplemental Table 4). To further characterize HRQoL improvements in adolescents, changes in subcomponent scores of the PedsQL were examined. Both the physical and psychosocial health scores improved through month 24 (mean changes at month 24, 12.4 points [SD, 15.5] and 12.0 points [SD, 10.4], respectively; n = 13), consistent with the change seen in total score (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3A; supplemental Table 4). Further examining the domains that compose the psychosocial health score, improvements were observed in all 3 domains assessed (eg, social, emotional, and school functioning; Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 3B; supplemental Table 5). Similar to the improvements in fatigue reported by adults, adolescents also noted improvements in their energy levels, with fewer adolescents reporting that they have low energy after exa-cel infusion (supplemental Figure 1B).

Changes from baseline in EQ-5D-Y VAS and US index score in adolescents in the primary efficacy set after exa-cel infusion

| Visit . | Statistic . | EQ-5D-Y VAS . | US health utility index score . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n | 19 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 81.3 (19.6) | 0.93 (0.12) | |

| Change at month 6 | n | 19 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (14.5) | 0.02 (0.10) | |

| Change at month 12 | n | 19 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (20.0) | 0.02 (0.10) | |

| Change at month 24 | n | 15 | 15 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (16.4) | 0.03 (0.07) |

| Visit . | Statistic . | EQ-5D-Y VAS . | US health utility index score . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n | 19 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 81.3 (19.6) | 0.93 (0.12) | |

| Change at month 6 | n | 19 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (14.5) | 0.02 (0.10) | |

| Change at month 12 | n | 19 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (20.0) | 0.02 (0.10) | |

| Change at month 24 | n | 15 | 15 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (16.4) | 0.03 (0.07) |

Baseline is defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (scheduled or unscheduled) collected before the start of mobilization.

Changes in PedsQL total and domain scores in adolescents in the PES after exa-cel infusion. (A) Mean changes in PedsQL total score, psychosocial score, and physical score from BL at months 12 and 24. (B) Mean changes in the psychosocial domains from BL at months 12 and 24. Dotted lines indicate the MCID for each measure. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. BL is defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (scheduled or unscheduled) collected before the start of mobilization. ∗Total score summarizes questions from the psychosocial and physical scores. ∗∗Psychosocial score summarizes questions from the emotional, social, and school function domains in panel B.

Changes in PedsQL total and domain scores in adolescents in the PES after exa-cel infusion. (A) Mean changes in PedsQL total score, psychosocial score, and physical score from BL at months 12 and 24. (B) Mean changes in the psychosocial domains from BL at months 12 and 24. Dotted lines indicate the MCID for each measure. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. BL is defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement (scheduled or unscheduled) collected before the start of mobilization. ∗Total score summarizes questions from the psychosocial and physical scores. ∗∗Psychosocial score summarizes questions from the emotional, social, and school function domains in panel B.

Discussion

Exa-cel was shown in a pivotal phase 3 clinical trial to increase levels of total Hb, as well as of HbF, and led to durable transfusion independence in more than 90% of patients with TDT.20 These results suggest exa-cel has the potential to fundamentally change TDT disease course. To further elucidate the benefits and broader impacts of exa-cel infusion on patient-perceived well-being in people with TDT, changes from baseline in PRO measures were assessed as a secondary end point in the exa-cel phase 3 pivotal trial. All PRO measures assessed in the CLIMB THAL-111 trial and CLIMB-131 extension trial, the largest PRO data set for patients with TDT after HSCT or gene therapy to date, showed sustained and consistent improvements after exa-cel infusion, indicating that participants who received exa-cel derived clinically meaningful improvement in their HRQoL.

The EQ-5D-5L has 2 components: the VAS provides a quantitative measure of the overall health status of an individual and a descriptive system of 5 dimensions of health and ability used to derive country-specific health utility index scores (EQ-5D-5L US and UK index scores).27-29 Overall, in adults with TDT, EQ-5D-5L measures improved after exa-cel infusion. This result is particularly meaningful given mean values for EQ-5D-5L VAS and EQ-5D-5L US and UK index scores were at or exceeded population norms at baseline. Although the mean baseline values were near normal relative to the general population, it is possible that such normal QoL scores could reflect response shift and/or an issue of content validity in the EQ-5D instrument for patients with TDT. Response shift is a common phenomenon in chronic diseases, whereby patients who have adapted to their conditions also adapt their perceptions of quality of life,30 and thus could explain the baseline patient-reported EQ-5D-5L scores. Another potential explanation for the normal baseline values is that the EQ-5D-5L instrument may lack content validity for people with TDT, and therefore, might not be able to fully capture disease burden in patients with this disease.31 Still, despite mean baseline values near population norms, increases in EQ-5D-5L measures were seen after exa-cel administration and were maintained over the course of the follow-up, strongly suggesting improvements in the HRQoL occurred. It should be acknowledged that these patient-reported increases in HRQoL after exa-cel infusion were in large part driven by participants in the trial who had EQ-5D-5L scores lower than the population norm at baseline (indicative of greater disease burden) and who contributed more to the observed changes in mean EQ-5D-5L values over time. However, it is also important to note that patients with TDT often report fluctuations of disease impact on their HRQoL based on their position within a transfusion cycle, often avoiding daily activities in the periods before RBC transfusions, but then resuming these activities afterwards due to the positive impacts of transfusion treatments.31 As over 90% of participants in the exa-cel trial became transfusion independent,20 it is highly likely such fluctuations in activity patterns, and their subsequent impacts on measures of HRQoL, were dramatically reduced or eliminated, which would then be reflected in the increased mean EQ-5D-5L results observed, and sustained after exa-cel infusion. Although population norms have yet to be established for adolescents, consistent with adults, adolescents had increases in EQ-5D-Y scores by month 6 that were sustained through month 24 after exa-cel infusion. Taken together, these results suggest overall health status improves in patients with TDT after infusion with exa-cel.

Whereas EQ-5D-5L provides information on overall health status, the FACT-BMT and PedsQL are different tools that can provide a means to examine specific aspects (or domains) of health status.25,32 After the administration of exa-cel, adults reported substantial and sustained improvements in their physical, social/family, functional, and emotional well-being beginning as early as month 6 after infusion and being sustained through month 48, with all changes at month 48 exceeding the established MCIDs. Similarly, adolescents had improvements in PedsQL physical score and psychosocial score (comprised of emotional, social and school function scores) starting as early as month 6 and being sustained through month 24, with all changes at month 24 exceeding the established MCIDs. These results suggest that exa-cel has early and broad impacts on multiple dimensions of health, including physical, emotional, social, and functional well-being, further validating the broad impact of exa-cel therapy on HRQoL in people with TDT.

In addition to achieving transfusion independence and improved HRQoL, both adults and adolescents also reported experiencing less fatigue after exa-cel infusion. This is particularly important as people with TDT often report suffering from severe fatigue before RBC tranfusion,11 which is likely the result of the anemia and reduced oxygen carrying capacity often leading to deconditioning and poor cardiopulmonary fitness necessitating ongoing regular RBC transfusions. Chronic anemia and the requirement for frequent RBC transfusions in people with TDT, and subsequent iron overload and need for regular iron removal therapy, can further reduce patient energy levels and quality of life. After exa-cel infusion, both adults and adolescents reported improvements in their energy levels, as soon as month 6, with continuing improvements seen throughout the follow-up period. This patient-reported improvement in energy levels is fully consistent with the increases in HbF and total Hb, and the elimination of RBC transfusions, previously reported in these patients after receiving exa-cel in the CLIMB THAL-111 trial.20 Furthermore, given that a subset of participants were able to discontinue iron removal therapy after exa-cel, future assessments of the impact of discontinuing chronic medications will be additionally informative as a contribution to improved quality of life and general well-being.

There are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the PRO tools used in this trial were not developed specifically for people with TDT. However, these validated tools are often used with other hematologic diseases, such as hematologic malignancies, and even if not developed specifically for these diseases, they have been shown to yield interpretable results. Second, the MCIDs used to interpret clinical benefit are not disease specific. These MCIDs have been developed for other hematologic (malignant) disease states that can be used to interpret clinical results generated from this data set. Third, previous studies have suggested that EQ-5D-5L lacks content validity and the derived health utility index scores may not fully represent the burden of disease for patients with TDT, thus potentially underestimating the extent of clinical benefit derived from exa-cel on HRQoL.31 Finally, trends over time should be interpreted with caution due to changing sample sizes, data variability, and smaller sample sizes at the longest times of available follow-up. In this perspective, the potential occurrence of fertility impairment related to the use of busulfan-based myeloablation could have a negative impact on patient’s quality of life. Future studies assessing PRO outcomes in a larger population of patients with TDT who have longer follow-up after exa-cel will be conducted to validate our results.

In conclusion, after exa-cel infusion, adults and adolescents with TDT had clinically meaningful and sustained improvements in HRQoL measures, with improvements seen across different instruments and domains, including physical, emotional, social/family, functioning well-beings, fatigue experience, and overall health status. These results confirm the broad, durable clinical and patient-important benefits, including improved quality of life, that exa-cel can provide to patients with TDT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in these trials, and all site trial investigators and coordinators for their contributions; Nathan Blow, and Concetta G. Marfella, of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, who own stock or stock options in the company, for providing medical writing and editorial support under the guidance of the authors; and Alexandra Battaglia, of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, who owns stock or stock options in the company, for providing graphical design support.

J.L.K. received support from National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant UL1TR001878).

The study sponsor (Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated) designed the protocol in collaboration with the academic authors. Site investigators collected the data, which were analyzed by the sponsor.

Authorship

Contribution: J.d.l.F., H.F., N.L., P.K., and F.L. developed the initial draft of the manuscript, with writing assistance from the sponsor; and all authors had full access to the study data, participated in subsequent revisions, and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.d.l.F. reports advisory and/or speaker fees from Beam Therapeutics, bluebird bio, Sangamo, Sanofi, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. H.F. reports consulting fees from Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, Editas Medicine, Rocket Pharmaceuticals; honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals; advisory fees from Rocket Pharmaceuticals; and served in a leadership or fiduciary position for Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. S.C. is an advisory board member for Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. D.W. is an advisory member for Editas Medicine and steering committee member for Editas Medicine and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. R.M. has been a consultant for Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, bluebird bio, Bristol Myers Squibb, CRISPR Therapeutics, Novartis, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated; and participated in clinical trials for CRISPR Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, Miltenyi Biotec, Novartis, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. A.M.L. is an advisory board member for Novartis Canada. A.J.S. has been a consultant for Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. B.C. is an advisory board member for Vertex Pharmaceuticals; and reports honoraria from bluebird bio. J.L.K. is on advisory boards for Agios Pharmaceuticals, bluebird bio, Chiesi USA, and Silence Therapeutics; participated in clinical trials for Bioverativ Therapeutics, bluebird bio, Sangamo, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated; and has been a consultant to Agios Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Celgene Corporation, Chiesi USA, Forma Therapeutics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Silence Therapeutics, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. M.A. is an advisory board member for Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. M.Y.M. has been a consultant for bluebird bio, CRISPR Therapeutics, Incyte Corporation, and Ossium Health. R.I.L. has participated in clinical trials for bluebird bio, Editas Medicine, Global Blood Therapeutics, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. K.H.M.K. reports grants or contracts from Agios Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer; consulting fees from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Agios, Biossil, Bristol Myers Squibb, Forma Therapeutics, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated; honoraria from Agios and Bristol Myers Squibb; and participated in a data safety monitoring board for Sangamo. H.M. reports an educational grant from Novartis; participated in clinical trials for Novartis, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, and Novo Nordisk; and reports advisory board participation and speaker engagements for Takeda, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, Sobi, Medison Pharma, Chiesi, Novo Nordisk, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. P.K., N.L., J. Rubin, S.Z., and W.H. are employees of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and may hold stock or stock options in the company. F.L. reports advisory board participation for Amgen, Neovii, Novartis, Sanofi, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated; and speakers' bureau participation for Amgen, bluebird bio, Gilead, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medac, Miltenyi Biotec, Neovi, Novartis, and Sobi. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the CLIMB THAL-111 and CLIMB-131 Study Groups appears in the “supplemental Material Appendix”

Correspondence: Franco Locatelli, Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, IRCCS, Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, Piazza Sant'Onofrio, 4, 00165 Rome, Italy; email: franco.locatelli@opbg.net.

References

Author notes

Vertex Pharmaceuticals is committed to advancing medical science and improving patient health. This includes the responsible sharing of clinical trial data with qualified researchers. Proposals for the use of these data will be reviewed by a scientific board. Approvals are at the discretion of Vertex and will be dependent on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, and the intended use of the data. For more information or submission of a proposal, please contact CTDS@vrtx.com.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.