Key Points

ARs are expressed at high levels in leukemia cells isolated from the murine preclinical model and in patient-derived AML cells.

Inhibition of AR signaling downregulated the RTK/GAB2, PI3K/AKT/MTOR, and SRC/HIF-1α signaling pathways in AML stem cells.

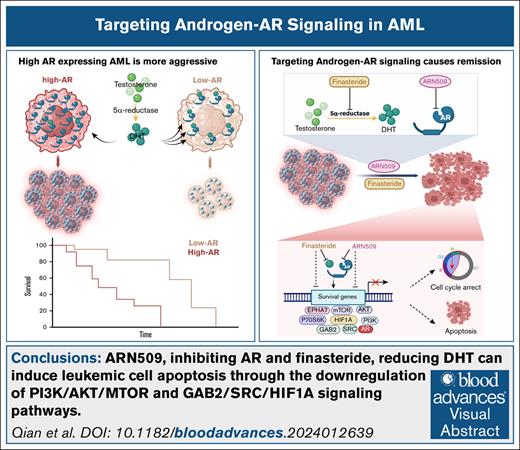

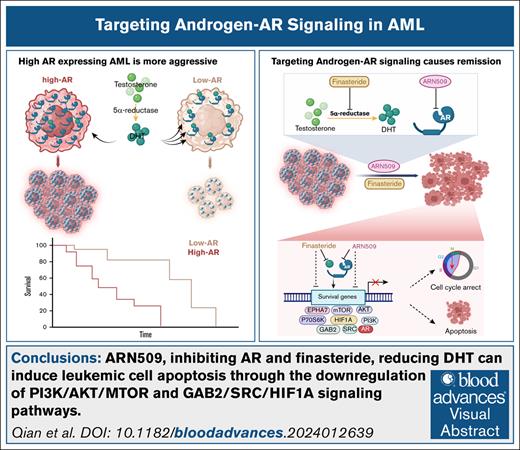

Visual Abstract

In addition to their role in development, sex hormones and their cognate receptors play an important role in various malignancies. Using a murine model of human mixed lineage leukemia-acute leukemia fused gene from chromosome 9 (MLL-AF9)–induced acute myeloid leukemia (AML), we discovered that high androgen receptor (AR)-expressing leukemia initiating cells (LICs), when transferred into either male or female recipients, produced more severe disease than low AR–expressing LICs. AR expression was significantly increased in female LICs when compared with male LICs. This difference was confined to the LICs and was not present in normal bone marrow cells. AML cells from both sexes relied on AR signaling via different mechanisms; females had high AR levels with low ligand levels and males had low AR levels with high ligand levels. AR expression was linked to the ephrin type-A receptor 7 (EPHA7)-associated PI3K/AKT/mTOR and SRC/HIF-1α pathways. The use of the 2 United States Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for prostate cancer, namely ARN509, an AR antagonist, and finasteride, which inhibits the pathway that produces dihydrotestosterone, led to significant remission with increased survival of the AML mice. ARN509 and finasteride also showed proapoptotic effects in patient-derived AML cells and in a humanized AML NOD scid gamma (NSG) mouse model. These data support a drug repurposing effort for the use of antiandrogen therapy to improve the efficacy of AML treatments.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by the infiltration of abnormally proliferating hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells into bone marrow, blood, and other tissues.1 In AML, a highly heterogeneous disease, cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities contribute to treatment resistance and relapse. A major challenge is minimal residual disease, which is driven by therapy-resistant, leukemia-initiating cells (LICs that share self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation capabilities with normal hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells. Targeting LICs could significantly improve AML treatment and prevent relapse.

Although the androgen receptor (AR) is well-characterized in prostate cancer in which it promotes tumor growth via androgen-dependent signaling, its role in hematologic malignancies, like AML, remains poorly understood.2,3 Androgen deprivation therapy reduces androgen levels to suppress prostate tumor progression.4 Beyond classical sex-specific cancers, steroid hormone receptors, like ARs and estrogen receptors (ERs), influence the susceptibility and progression of various cancers.5 For instance, low estrogen levels may increase male susceptibility to acute lymphoid leukemia6 while promoting thyroid cancer in females.7 Conversely, androgen can drive male-biased aggression in cancers, such as bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma by activating ARs in antitumor cytotoxic (CD8+) T cells.8,9 However, conflicting data in lung and breast cancers indicate that the role of steroid metabolism in cancer is complex and not fully defined.10-12 High concentrations of estrogen and androgen display cytotoxic effects on leukemic cell lines in a receptor-independent manner.13,14 The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data sets associate high AR messenger RNA (mRNA), but not protein, with favorable AML survival.15 A clinical trial reported that stanozolol in combination with maintenance therapy prolonged AML survival via stimulating myeloid proliferation,16 but a follow-up trial showed no benefit.17 Overall, AR/androgen signaling in AML lacks robust validation.

In a murine MLL-AF9 AML model, the transfer of high AR-expressing LICs led to more severe disease than transfer of low AR-expressing LICs. Female-derived LICs showed higher AR expression than those derived from males; however, AR signaling mechanisms differed by sex: females had high AR levels but low ligand levels, whereas males had low AR levels but high ligand levels. Finasteride (a 5-α reductase inhibitor) and ARN509 (apalutamide; Erleada, AR antagonists) significantly delayed AML progression in both genders. Combination therapy also suppressed leukemia in a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model of human AML. High AR-expressing LICs activated EPHA7-associated PI3K/AKT/MTOR and SRC/HIF-1α pathways, offering new avenues for anti-AR therapy in AML.

Materials and methods

The supplemental Materials and Methods contain additional details.

Mice

Male and female C57BL/6 mice and ovariectomized (OVX) and OVX-sham mice were acquired from Taconic Biosciences. B6.Cg-Rptortm1.1Dmsa/J female mice and female and male NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ mice, also known as NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice, were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. CD45.1 male and female mice were bred in house. Information about the age and gender of mice used in each experiment were included in the figure legends. All mice were fed normal chow and provided with Milli-Q water ad libitum.

Establishment of primary (1°) AML mouse models

Bone marrow cells that were flushed from the tibias and femurs isolated from CD45.1 donor mice were applied to stem/progenitor cell isolation using EasySep mouse hematopoietic progenitor cell isolation kit (Stemcell; catalog no. 19856), followed by red blood cell (RBC) lysis with ACK (Ammonium Chloride Potassium) lysis buffer (155 mM NH4Cl, 12 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA-2Na) to enrich for lineage negative (Lin–) cells. Lin– cells were stained for stem cell markers, that is, Ly-6A/E (Sca-1) and CD117 (c-kit), followed by the isolation of Sca-1+c-Kit+ cells on a Beckman Coulter MoFlo Astrios EQ Cell Sorter. Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were cultured in conditioned Iscove modified Dulbecco medium containing MLL-AF9 retrovirus for 6 hours and then injected retro-orbitally into sublethally irradiated (4.75 Gys) CD45.2 recipient mice (supplemental Figure 1A). For tamoxifen-inducible Raptor–/– (Raptor TAM-iKO) AML, B6.Cg-Rptortm1.1Dmsa/J CD45.2 female mice were used as donors and CD45.1 male mice were used as recipients. Four models were generated in this study, and the corresponding donor and recipient mice are listed in supplemental Figure 1B. Primary AML cells isolated from the bone marrow and spleen of recipients were used for in vitro studies and serial transplantation.

Serial transplantation and survival analyses

Secondary (2°) AML transplantation was performed via retro-orbital injection of 4 × 105 CD45.1 AML cells into CD45.2 recipients (Raptor TAM-iKO: CD45.2 to CD45.1) without irradiation. Mice were monitored for up to 60 days (120 for OVX/OVX-Sham) or until death, the white blood cell (WBC) count reached >5 × 104/μL, paralysis, immobility, or hypothermia as end point events.

Establishment of a PDX AML model in NSG mice

A PDX AML model was generated by retro-orbitally injecting 5 × 105 patient-derived high AR–expressing AML cells per mouse into female and male NSG mice. On day 90 after transplantation, engraftment of patient-derived AML cells was confirmed by complete blood count with peripheral WBCs reaching 2000 to 3000/μL.

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow and whole spleen cells were isolated from mice at the end point. Bone marrow cells were flushed out from femurs and tibias by using flow buffer, followed by RBC lysis. Whole spleen cells were isolated by meshing the spleen with flow buffer in 70-μm cell strainers, followed by RBC lysis. Single-cell suspensions were used to isolate Lin– cells using EasySep mouse hematopoietic progenitor cell isolation kit (STEMCELL), followed by staining with CD45.1, Cd117 (c-Kit), and Ly-6A/E (Sca-1) fluorescent antibodies. Raw data of the Lin– cell numbers and the presence of LICs were collected on an BD Accuri C6 and analyzed using FlowJo, version 10. AML LICs were identified as CD45.1+Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+.

The intracellular staining assay has been described previously.18 Briefly, AML cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-CD45.1 antibody in flow buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 40 minutes, followed by permeabilization for 50 minutes and staining with the separate primary antibodies (phospho-4E-binding protein 1 (p-4E-BP1) and phospho-S6K (S-6-kinase), 1:100) in permeabilization buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature. Raw data were collected on a BD Accuri C6 and subsequently analyzed using FlowJo, version 10; AML cells were pregated and identified as the CD45.1+ population.

For the NSG mice, nucleated cells were isolated from blood, bone marrow, and spleen at the end point. Engrafted patient-derived AML cells were identified by flow cytometry and staining with human CD45 antibody.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, v6, and the data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. One-tailed unpaired t tests, 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc test, and 2-way analysis of variance were used as appropriate. Survival was assessed using the log-rank test. P < .05 was considered significant (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01).

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Pennsylvania State University.

Results

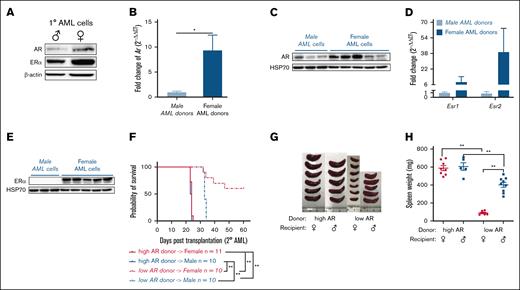

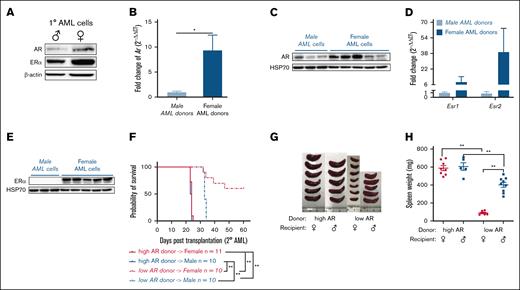

Expression of ARs and ERs is increased in AML cells

The 1° MLL-AF9 LICs were generated and transplanted into secondary recipients as described (supplemental Figure 1A-B). The 1° AML cells showed higher AR and ER expression, particularly in the ones generated from female HSC donors (Figure 1A). This distinct expression pattern of ARs and ERs was seen in 2° AML (Figure 1B-E). Thus, bone marrow HSCs isolated female and male donor mice were used to generate naturally high and low AR–expressing AML cells, respectively, for this study. In addition, a more aggressive disease was seen in the form of decreased survival after 2° transplantation (Figure 1F) and increased splenomegaly (Figure 1G-H) in mice transplanted with high AR and ER expressing AML cells, regardless of recipient’s sex, indicating a possible association between AR and/or ER expression in AML cells and survival. Female mice transplanted with low AR–expressing AML cells lived longer with minimal disease. This may partly explain the inability to induce the disease in other studies involving similar experimental models in which AR expression was not considered.19

AR expression in AML cells affects survival. (A) Western blot showing the expression of ARs and ERαs in purified 1° wild-type (WT) male and female AML cells. (B) Expression of Ar as assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in WT male and female AML cells. Data were normalized to WT male AML cells and Gapdh housekeeping gene (n = 8-10 biologic replicates). (C) Western blot showing the expression of ARs in WT male and female AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (D) Expression of Esr1 and Esr2 assessed by qPCR in WT male and female AML cells. The data were normalized to WT male AML cells and Gapdh housekeeping gene (n = 3-10 biologic replicates). (E) Western blot showing the expression of ERα in WT male and female AML cells. (F) Survival curve of WT female and male recipient mice secondarily transplanted with WT high and low AR–expressing AML donor cells (n = 10-11 in each group); Log-rank tests were used to indicate significance with ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .01. (G) Representative image of spleens isolated from recipients in panel F at the end point. (H) Spleen weights (mg) of recipient mice in panel F at the end point. Panels B,D,H, error bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by 1-tailed unpaired Student t test.

AR expression in AML cells affects survival. (A) Western blot showing the expression of ARs and ERαs in purified 1° wild-type (WT) male and female AML cells. (B) Expression of Ar as assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in WT male and female AML cells. Data were normalized to WT male AML cells and Gapdh housekeeping gene (n = 8-10 biologic replicates). (C) Western blot showing the expression of ARs in WT male and female AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (D) Expression of Esr1 and Esr2 assessed by qPCR in WT male and female AML cells. The data were normalized to WT male AML cells and Gapdh housekeeping gene (n = 3-10 biologic replicates). (E) Western blot showing the expression of ERα in WT male and female AML cells. (F) Survival curve of WT female and male recipient mice secondarily transplanted with WT high and low AR–expressing AML donor cells (n = 10-11 in each group); Log-rank tests were used to indicate significance with ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .01. (G) Representative image of spleens isolated from recipients in panel F at the end point. (H) Spleen weights (mg) of recipient mice in panel F at the end point. Panels B,D,H, error bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by 1-tailed unpaired Student t test.

ER signaling does not affect AML progression

To determine whether ER signaling potentiated the differences in AML progression, we transplanted AML donor cells into estrogen-deprived OVX or sham control mice. However, estrogen deprivation via oophorectomy failed to show any impact on leukocytosis between the 2 groups (supplemental Figure 2A). More importantly, OVX mice showed no survival advantage over sham control mice with AML (supplemental Figure 2B). Specifically, 3 OVX mice developed AML, and 1 mouse was diagnosed with an unrelated spinal tumor, whereas the other 3 mice survived till the end point. In contrast, all 7 sham control mice were euthanized because of the development of AML (n = 3), spinal tumor (n = 1), or uterine hyperplasia (n = 3) before the end point (supplemental Figure 2C-E). Quantitatively, estrogens circulate at lower levels than androgens in both men and women,20 leading us to examine the role of androgenic hormones and AR signaling in our experimental model of AML.

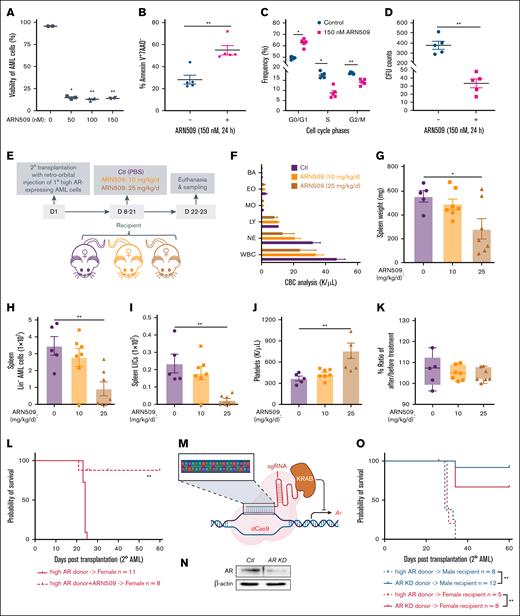

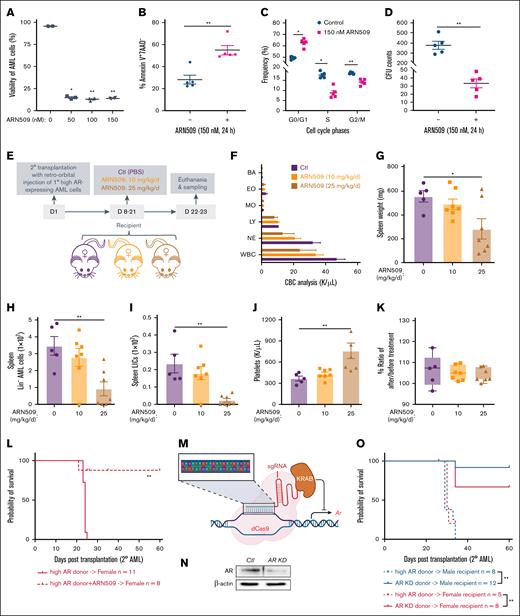

Enhanced AR expression increases the aggressiveness of AML donor cells

To determine if AR signaling accounted for the differences in leukemogenesis, we utilized ARN509, a clinically relevant and selective antagonist of AR, to treat high AR–expressing AML cells. We observed decreased cell viability after 24 hours of treatment (Figure 2A), along with increased apoptosis, cell cycle arrest in the S and G/2/M phases, and decreased proliferation and colony forming capacity (Figure 2B-D), highlighting the therapeutic potential of ARN509. Furthermore, ARN509 treatment of female recipient mice transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells at a dose of 10 or 25 mg/kg daily for 2 weeks (Figure 2E) displayed a dose-dependent improvement in leukocytosis and splenomegaly (Figure 2F-G). Consistently, ARN509 treatment also limited the cancer progression by targeting the AML bulk cells (Figure 2H), as well as the LIC population (Figure 2I), identified as Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+ cells,21,22 in the spleen of recipient mice. The treatment was well tolerated with mice showing minimal changes in body weight and having significantly increased platelets at the highest dose (Figure 2J-K). To determine if ARN509 treatment provided any survival benefit, high AR–expressing AML cells were cultured in the presence of 150 nM ARN509 for 24 hours ex vivo, followed by transplantation into female recipients (Figure 2L). Antagonism of AR in high AR–expressing AML cells by ARN509 limited the engraftment of these cells, leading to improved survival in the mice (Figure 2L).

Enhanced AR expression increases the aggressiveness of AML donor cells. (A) Viability of 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells treated with ARN509 at 0, 50, 100, and 150 nM for 24 hours (n = 4). The frequency of CD45.1+ AML cells was assessed by flow cytometry. (B) The frequency of the Annexin V+7AAD– population in 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells treated with ARN509 at 0 or 150 nM for 24 hours (n = 5) pregated for the identification of CD45.1 by flow cytometry. (C) Cell cycle analysis of 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells treated with ARN509 at 0 or 150 nM for 24 hours (n = 5). The cells were first gated on Forward Scatter-Area/Height, FSC-A/FSC-H, and FSC-A and Side Scatter-Area, SSC-A, to acquire singlets. AML cells were identified as the CD45.1+ population and further evaluated for cell cycle phase using the Dean-Jet-Fox model in the FlowJo software program. (D) Primary WT high AR–expressing AML cells were plated in methylcellulose medium (2500 cells per well, 4 replicates) with/without 150 nM ARN509. The CFUs were counted on day 8. (E) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 WT high AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT female recipients; at 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered ARN509 daily at 10 mg/kg or 25 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 2 weeks. Mice were euthanized at 3 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 5-7 in each group). (F) Complete blood count (CBC) analysis of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (G) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (H-I) Counts of AML cells in the Lin– (H) and LIC (I) populations in the spleen of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (J) Count of platelets in the periphery of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (K) Body weight change expressed as the ratio of body weight before the treatment and at the end point in panel E. (L) A Kaplan-Meier curve was generated to estimate the survival of female recipients transplanted with 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells after in vitro culture in the absence or presence of 150 nM ARN509. Survival was followed up for 60 days after transplantation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a log-rank test. (M) Illustration showing the targeted knockdown of Ar by a CRISPR interference technique that targets the promoter of Ar. (N) Knockdown of AR was assessed by western blot. (O) Survival analysis of 2° male and female recipients transplanted with WT high AR–expressing or AR KD AML cells; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a log-rank test. Panels A-D, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of the replicates. ∗P< .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. Panels G-K, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. BA, basophil; Ctl, control; CFU, colony forming unit; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Enhanced AR expression increases the aggressiveness of AML donor cells. (A) Viability of 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells treated with ARN509 at 0, 50, 100, and 150 nM for 24 hours (n = 4). The frequency of CD45.1+ AML cells was assessed by flow cytometry. (B) The frequency of the Annexin V+7AAD– population in 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells treated with ARN509 at 0 or 150 nM for 24 hours (n = 5) pregated for the identification of CD45.1 by flow cytometry. (C) Cell cycle analysis of 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells treated with ARN509 at 0 or 150 nM for 24 hours (n = 5). The cells were first gated on Forward Scatter-Area/Height, FSC-A/FSC-H, and FSC-A and Side Scatter-Area, SSC-A, to acquire singlets. AML cells were identified as the CD45.1+ population and further evaluated for cell cycle phase using the Dean-Jet-Fox model in the FlowJo software program. (D) Primary WT high AR–expressing AML cells were plated in methylcellulose medium (2500 cells per well, 4 replicates) with/without 150 nM ARN509. The CFUs were counted on day 8. (E) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 WT high AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT female recipients; at 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered ARN509 daily at 10 mg/kg or 25 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 2 weeks. Mice were euthanized at 3 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 5-7 in each group). (F) Complete blood count (CBC) analysis of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (G) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (H-I) Counts of AML cells in the Lin– (H) and LIC (I) populations in the spleen of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (J) Count of platelets in the periphery of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (K) Body weight change expressed as the ratio of body weight before the treatment and at the end point in panel E. (L) A Kaplan-Meier curve was generated to estimate the survival of female recipients transplanted with 1° WT high AR–expressing AML cells after in vitro culture in the absence or presence of 150 nM ARN509. Survival was followed up for 60 days after transplantation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a log-rank test. (M) Illustration showing the targeted knockdown of Ar by a CRISPR interference technique that targets the promoter of Ar. (N) Knockdown of AR was assessed by western blot. (O) Survival analysis of 2° male and female recipients transplanted with WT high AR–expressing or AR KD AML cells; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a log-rank test. Panels A-D, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of the replicates. ∗P< .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. Panels G-K, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. BA, basophil; Ctl, control; CFU, colony forming unit; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

The antileukemic effect of ARN509 was further verified by treating male recipient mice that were transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells with ARN509 at 10 and 25 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks (supplemental Figure 3A). Treatment with ARN509 effectively reduced leukocytosis and splenomegaly in male recipients (supplemental Figure 3B-C). Furthermore, these mice also exhibited slower AML progression with a decline in the Lin– population and LICs in the bone marrow and spleen upon ARN509 treatment (supplemental Figure 3D-G). We also observed increased platelets and steady body weights upon treatment with 25 mg/kg per day ARN509 (supplemental Figure 3H-I).

To specifically elucidate the role of AR in AML cells, the expression of AR was selectively downregulated by targeting its promoter region using CRISPR interference (Figure 2M). Following confirmation of the efficiency of knockdown of AR by western blot (Figure 2N), transplantation of AR knockdown AML cells into either male or female recipient mice showed attenuated aggressiveness and improved survival of recipients when compared with high AR–expressing transplant recipient mice (Figure 2O).

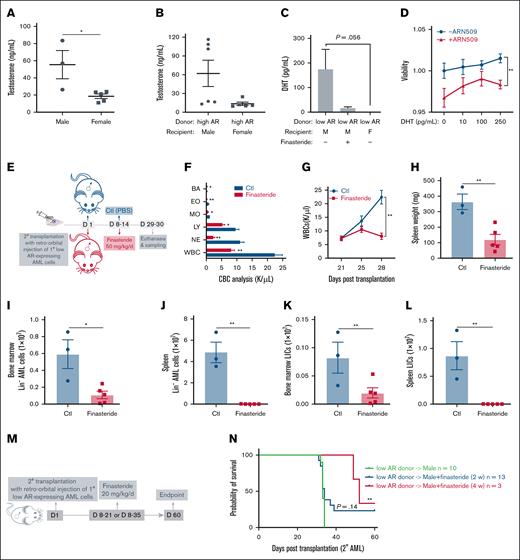

Endogenous AR ligands promote AML

Similar to what we observed in high AR–expressing LICs, the treatment of low AR–expressing LICs with ARN509 ex vivo also induced dose-dependent apoptosis (supplemental Figure 3J). However, when low AR–expressing LICs that were treated with ARN509 were transplanted into male recipients, we observed a trend toward increased survival with no significant difference (supplemental Figure 3K). Although AR signaling seems to promote leukemic progression, differences in the aggressiveness of high and low AR–expressing AML donor cells may also be influenced by variations in androgen production in the recipient mice.

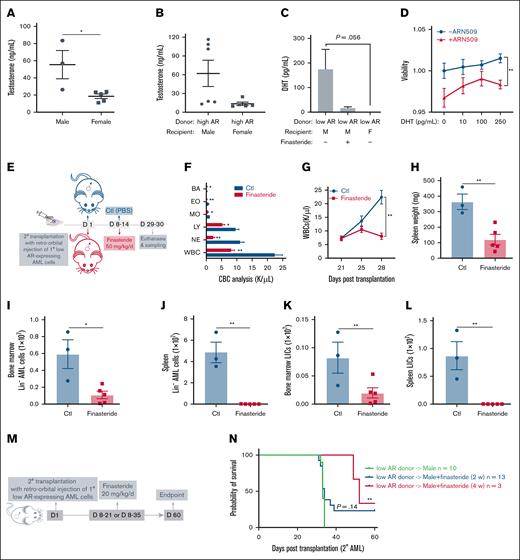

We tested whether androgenic hormones exert a proleukemic effect on AML donor cells of either sex and whether differences in the androgen levels contribute to the varying susceptibility of male and female recipients to AML. As expected, circulating testosterone levels were lower in female mice than their age-matched male counterparts in both healthy (Figure 3A) and AML mice (Figure 3B). Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the active metabolite of testosterone and the most potent endogenous ligand of AR, was significantly lower in female AML mice but abundant in male AML mice. The DHT levels decreased upon finasteride treatment (Figure 3C). To examine the direct effect of DHT on AML cells, low AR–expressing AML cells were cultured in the presence of DHT with or without ARN509. We observed a steady increase in the viability of cells with increasing concentrations of DHT. However, such an increase was abrogated in the presence of ARN509 (Figure 3D), implying an androgen-dependent mechanism that facilitates the growth of AML cells, even though they express low levels of ARs. Furthermore, finasteride treatment of male recipient mice, transplanted with low AR–expressing AML cells, significantly reduced leukocytosis (Figures 3E-F). The progression of AML was slower in male mice treated with finasteride and WBC counts were attenuated in the peripheral blood (Figure 3G), splenomegaly was resolved (Figure 3H), and leukemic burden (AML cell counts) was reduced in the bone marrow and spleen (Figure 3I-J). More importantly, LICs were dramatically lowered by finasteride treatment in the bone marrow and spleen (Figure 3K-L). The long-term effects of finasteride on survival were assessed in male mice transplanted with low AR-expressing AML cells following 2- and 4-week treatment regimens (Figure 3M). Although 2-week finasteride treatment had no statistically significant impact on survival, a 4-week regimen significantly prolonged survival after transplantation (Figure 3N).

Androgen signaling induces increased susceptibility to AML in male recipients. (A-B) The measurement of serum testosterone level in (A) healthy WT male (n = 3) and female (n = 5) mice and (B) WT male (n = 6) and female (n = 5) recipients transplanted with 1° high AR–expressing AML donor cells at the end point. (C) Measurement of the serum DHT level in WT male recipients transplanted with low AR–expressing AML donor cells in the absence or presence of in vivo finasteride treatment and WT female recipients transplanted with low AR–expressing AML donor cells at the end point (n = 3-5). (D) Viability of purified 1° low AR–expressing AML cells treated with DHT (0, 10, 100, 250 pg/mL; n = 4) in the absence or presence of 150 nM ARN509 for 24 hours. (E) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 low AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT male recipients; at 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered 50 mg/kg finasteride daily intraperitoneally for a week. Mice were euthanized at 4 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 3-5 in each group). (F) CBC analysis of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (G) Progression of the peripheral WBC numbers in recipient mice in panel E after transplantation. (H) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (I-J) Counts of AML cells in the Lin- population in the bone marrow (I) and spleen (J) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (K-L) Counts of LICs in the bone marrow (K) and spleen (L) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (M) Scheme showing male recipients transplanted with low AR–expressing AML cells and that subsequently received in vivo intraperitoneal treatment of finasteride (20 mg/kg per day) for 2 or 4 weeks. (N) Kaplan-Meier curve used to estimate the survival benefit of in vivo finasteride treatment; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a log-rank test. Panels A-C, F, H-L, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. Panels D,G, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a 1-way ANOVA test. BA, basophil; Ctl, control; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Androgen signaling induces increased susceptibility to AML in male recipients. (A-B) The measurement of serum testosterone level in (A) healthy WT male (n = 3) and female (n = 5) mice and (B) WT male (n = 6) and female (n = 5) recipients transplanted with 1° high AR–expressing AML donor cells at the end point. (C) Measurement of the serum DHT level in WT male recipients transplanted with low AR–expressing AML donor cells in the absence or presence of in vivo finasteride treatment and WT female recipients transplanted with low AR–expressing AML donor cells at the end point (n = 3-5). (D) Viability of purified 1° low AR–expressing AML cells treated with DHT (0, 10, 100, 250 pg/mL; n = 4) in the absence or presence of 150 nM ARN509 for 24 hours. (E) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 low AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT male recipients; at 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered 50 mg/kg finasteride daily intraperitoneally for a week. Mice were euthanized at 4 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 3-5 in each group). (F) CBC analysis of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (G) Progression of the peripheral WBC numbers in recipient mice in panel E after transplantation. (H) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (I-J) Counts of AML cells in the Lin- population in the bone marrow (I) and spleen (J) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (K-L) Counts of LICs in the bone marrow (K) and spleen (L) of recipient mice in panel E at the end point. (M) Scheme showing male recipients transplanted with low AR–expressing AML cells and that subsequently received in vivo intraperitoneal treatment of finasteride (20 mg/kg per day) for 2 or 4 weeks. (N) Kaplan-Meier curve used to estimate the survival benefit of in vivo finasteride treatment; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a log-rank test. Panels A-C, F, H-L, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. Panels D,G, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a 1-way ANOVA test. BA, basophil; Ctl, control; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

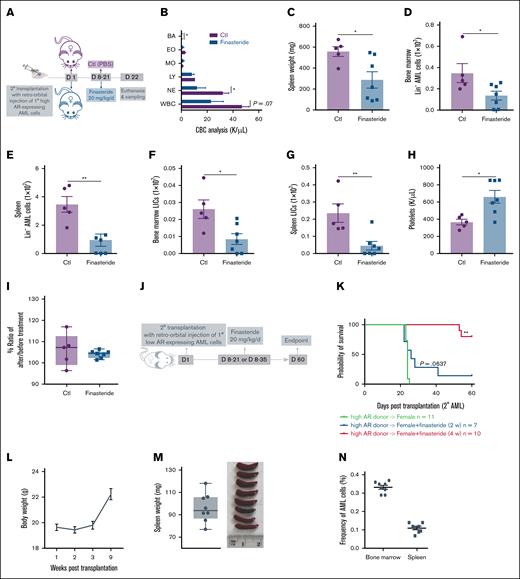

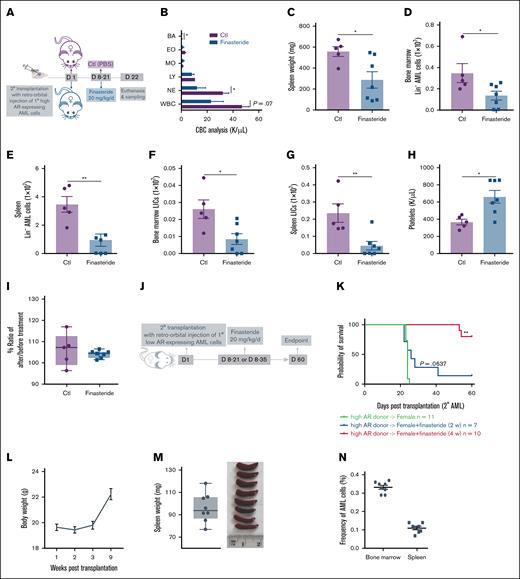

We next tested the antileukemic effect of finasteride in female mice transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells (Figure 4A). Finasteride-treated female AML mice also showed improved leukocytosis (Figure 4B) and splenomegaly (Figure 4C), in addition to decreased leukemic burden, including LICs, in the bone marrow and spleen (Figure 4D-G). In addition, platelet recovery and unchanged body weights were indicative of hematologic improvement (Figure 4H-I). The long-term benefit of finasteride was also evaluated in female AML mice that were transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells and subjected to 2- or 4-week finasteride treatment and followed up to 60 days (Figure 4J) after transplantation. Mice on 4-week finasteride treatment clearly showed a significantly improved survival (Figure 4K), along with gradual weight gain (Figure 4L) and splenomegaly was resolved, in addition to negligible leukemic burden in the bone marrow and spleen at euthanasia (Figure 4M-N).

Blockage of DHT production in female recipients transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells improves the disease outcome. (A) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 high AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT female recipients; at 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered 20 mg/kg finasteride daily intraperitoneally for 2 weeks. The mice were euthanized at 3 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 5-7 in each group). (B) CBC analysis of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (C) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (D-E) Counts of AML cells in the Lin– population in the bone marrow (D) and spleen (E) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (F-G) Counts of LICs in the bone marrow (F) and spleen (G) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (H) Count of platelets in the periphery of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (I) Body weight change, expressed as the ratio of body weight before the treatment and at the end point in panel A. (J) Scheme showing female recipients transplanted with high AR–expressing AML donor cells that received the in vivo treatment of intraperitoneal finasteride (20 mg/kg per day) for 2 or 4 weeks. (K) The Kaplan-Meier curve that was used to estimate the survival benefit of in vivo finasteride treatment up to 63 days after transplantation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a log-rank test. (L) Eight mice in the group of female recipients that were treated with 4 weeks of finasteride (high AR–expressing donor → female + finasteride 4 week) in panel K were euthanized at day 63. The body weights of those mice were measured after transplantation. (M) Spleen weights (mg) of the recipient mice in panel L at the end point. (N) Counts of CD45.1+ AML cells in the bone marrow and spleen of mice in panel L at the end point. Panels B-I, M-N, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of the replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. BA, basophil; Ctl, control; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Blockage of DHT production in female recipients transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells improves the disease outcome. (A) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 high AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT female recipients; at 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered 20 mg/kg finasteride daily intraperitoneally for 2 weeks. The mice were euthanized at 3 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 5-7 in each group). (B) CBC analysis of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (C) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (D-E) Counts of AML cells in the Lin– population in the bone marrow (D) and spleen (E) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (F-G) Counts of LICs in the bone marrow (F) and spleen (G) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (H) Count of platelets in the periphery of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (I) Body weight change, expressed as the ratio of body weight before the treatment and at the end point in panel A. (J) Scheme showing female recipients transplanted with high AR–expressing AML donor cells that received the in vivo treatment of intraperitoneal finasteride (20 mg/kg per day) for 2 or 4 weeks. (K) The Kaplan-Meier curve that was used to estimate the survival benefit of in vivo finasteride treatment up to 63 days after transplantation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a log-rank test. (L) Eight mice in the group of female recipients that were treated with 4 weeks of finasteride (high AR–expressing donor → female + finasteride 4 week) in panel K were euthanized at day 63. The body weights of those mice were measured after transplantation. (M) Spleen weights (mg) of the recipient mice in panel L at the end point. (N) Counts of CD45.1+ AML cells in the bone marrow and spleen of mice in panel L at the end point. Panels B-I, M-N, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of the replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined using a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. BA, basophil; Ctl, control; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

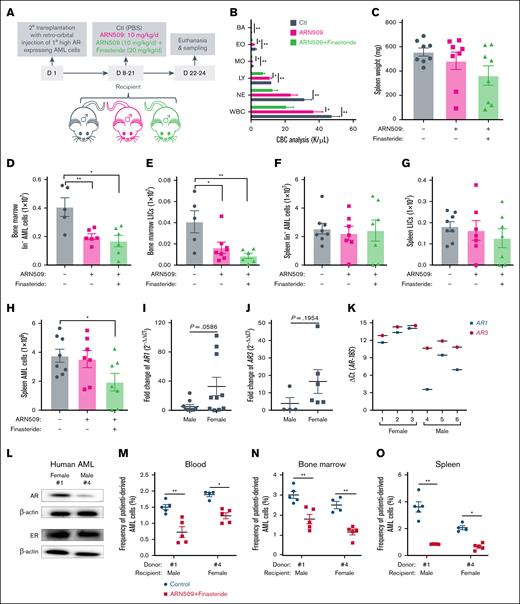

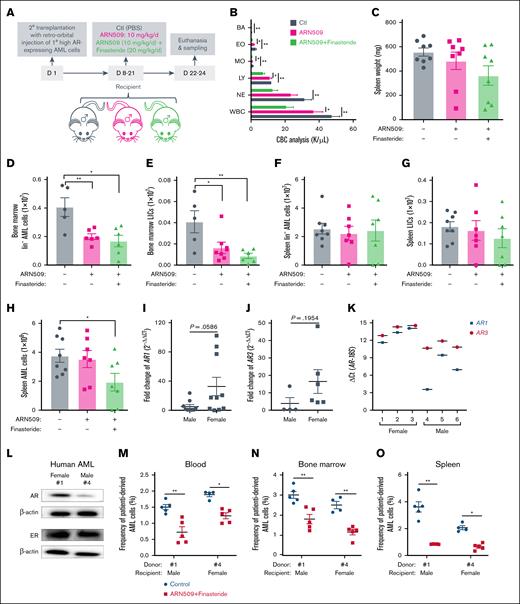

Furthermore, the use of finasteride with ARN509 in male recipients transplanted with high AR–expressing AML cells indicated that the addition of finasteride significantly improved the leukocytosis in ARN509-treated mice and further reduced the splenomegaly (Figure 5A-C). The combination treatment was highly effective in bone marrow but not to the same extent as in the spleen in which the Lin– and LIC populations of AML cells were significantly reduced (Figure 5D-G). Despite the organ-specific effect, the total AML burden was decreased in the spleen of mice that received the combination treatment (Figure 5H).

Combined inhibition of androgen production and ARs on high AR–expressing AML cells improves the outcome of AML. (A) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 high AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT male recipients. At 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered daily ARN509 at 10 mg/kg with or without finasteride at 20 mg/kg per day intraperitoneally for 2 weeks. The mice were euthanized at 3 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 5-7 in each group). (B) CBC analysis of the recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (C) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (D-G) Counts of the AML cells in the Lin- population and LICs in the bone marrow (D-E) and spleen (F-G) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (H) Counts of the total AML cells in the spleen of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (I-J) qPCR analysis of AR1 (I) and AR3 (J) in AML cells derived from male (n = 10) and female (n = 10) patients. The data were normalized to male patient–derived AML cells and the 18S (RPS18) housekeeping gene. Patient samples that exhibited undetectable expressions were excluded. (K) qPCR analysis of AR1 and AR3 in AML cells derived from female (n = 3) and male (n = 3) patients. The data were presented as ΔCt. (L) A western blot showing the expression of ARs and ERs in female (1) and male (4) patient-derived AML cells. (M-O) Female (1) and male (4) patient-derived AML cells were transplanted retro-orbitally (500 000 cells per mouse) into 10 male and 10 female 11-week-old NSG mice under lethal irradiation (9.5 Gys), respectively. At day 90 after transplantation when the peripheral WBC levels reached 2000 to 3000/μL, mice were treated with or without finasteride (20 mg/kg) and ARN509 (25 mg/kg) intraperitoneally daily for 14 days. At day 127 after transplantation, these mice were euthanized, and the human cells were tested in peripheral blood (M), bone marrow (N), and spleen (O), following identification as human CD45+ cells by flow cytometry. Panels B-K, M-O, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. BA, basophil; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil.

Combined inhibition of androgen production and ARs on high AR–expressing AML cells improves the outcome of AML. (A) Secondary transplantation was done retro-orbitally with 1° CD45.1 high AR–expressing AML donor cells to CD45.2 WT male recipients. At 1 week after transplantation, the mice were administered daily ARN509 at 10 mg/kg with or without finasteride at 20 mg/kg per day intraperitoneally for 2 weeks. The mice were euthanized at 3 weeks after transplantation; the blood, bone marrow, and spleen were sampled (n = 5-7 in each group). (B) CBC analysis of the recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (C) Spleen weights (milligram) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (D-G) Counts of the AML cells in the Lin- population and LICs in the bone marrow (D-E) and spleen (F-G) of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (H) Counts of the total AML cells in the spleen of recipient mice in panel A at the end point. (I-J) qPCR analysis of AR1 (I) and AR3 (J) in AML cells derived from male (n = 10) and female (n = 10) patients. The data were normalized to male patient–derived AML cells and the 18S (RPS18) housekeeping gene. Patient samples that exhibited undetectable expressions were excluded. (K) qPCR analysis of AR1 and AR3 in AML cells derived from female (n = 3) and male (n = 3) patients. The data were presented as ΔCt. (L) A western blot showing the expression of ARs and ERs in female (1) and male (4) patient-derived AML cells. (M-O) Female (1) and male (4) patient-derived AML cells were transplanted retro-orbitally (500 000 cells per mouse) into 10 male and 10 female 11-week-old NSG mice under lethal irradiation (9.5 Gys), respectively. At day 90 after transplantation when the peripheral WBC levels reached 2000 to 3000/μL, mice were treated with or without finasteride (20 mg/kg) and ARN509 (25 mg/kg) intraperitoneally daily for 14 days. At day 127 after transplantation, these mice were euthanized, and the human cells were tested in peripheral blood (M), bone marrow (N), and spleen (O), following identification as human CD45+ cells by flow cytometry. Panels B-K, M-O, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. BA, basophil; EO, eosinophil; LY, lymphocyte; MO, monocyte; NE, neutrophil.

To further extend our findings to clinical patients, we first analyzed the expression of AR mRNA (AR1 and AR3) in AML cells derived from female (n = 10) and male (n = 10) patients. Interestingly, female patient–derived AML cells showed an increase in AR1 and AR3 expression, along with significant variation within the group when compared with their male patient counterparts (Figure 5I-J). To explore the clinical application of anti-AR signaling treatment in AML, we established an AML PDX model by transplanting patient-derived, high AR–expressing AML cells into NSG mice. AML cells isolated from 3 female and 3 male patients exhibited variable mRNA expression levels of AR1 and AR3 (Figure 5K), and cells from the female (1) and male (4) patients with the highest AR expression were selected for further validation. Notably, male (4) AML cells showed more AR mRNA expression but a lower protein expression than female (1) AML cells, but there was no significant differences in ER expression between them (Figure 5L). A total of 10 male and 10 female NSG mice were transplanted with the above AML cells from the female (1) and male (4) patients, respectively. After 90 days of engraftment, treatment with ARN509 and finasteride reduced the leukemic burden in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and spleen in both PDX models (Figure 5M-O), supporting their potential for AML therapy in clinical trials.

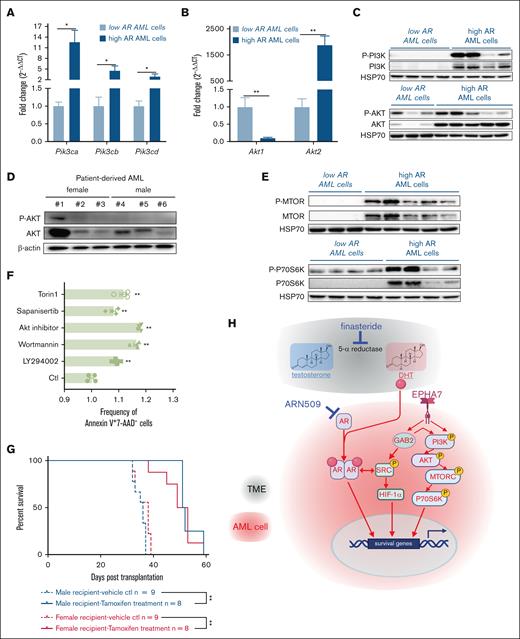

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is upregulated to mediate the increased aggressiveness of AML cells

AR signaling engages in complex crosstalk with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways to promote prostate tumorigenesis.23,24 In this study, we examined if high AR–expressing AML cells used this pathway to enhance aggressiveness. When compared with low AR–expressing AML cells, high AR–expressing AML cells expressed higher levels of PI3K (Pik3ca, Pik3cb, and Pik3cd) (Figure 6A) and Akt2, whereas Akt1 was downregulated (Figure 6B). Consistent with this, the expression and activity of PI3K and AKT (seen in the phosphorylated forms, P-PI3K and P-AKT) were increased in high AR–expressing AML cells (Figure 6C), which was also confirmed in the patient-derived high AR–expressing AML cells (Figure 6D). Significant upregulation of mTOR and p70S6K expression and activity (as P-mTOR and P-p70S6K) was seen in the high AR–expressing AML cells (Figure 6E). Similar results were also observed in purified 1° AML cells (supplemental Figure 4A). Because p70S6K is phosphorylated by mTORC1, these data suggest that PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling potentiates the increased aggressiveness in high AR–expressing AML cells by augmenting the expression and activity of its components. Thus, we used various pharmacologic inhibitors to manipulate the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling axis in high AR–expressing AML cells. In vitro treatment of AML cells with inhibitors of PI3K (LY294002 and wortmannin), AKT (Akt inhibitor), or mTORC (sapanisertib and torin1) induced apoptosis in high AR–expressing AML cells (Figure 6F), along with decreased phosphorylation of p70S6K and 4-E-BP1 (supplemental Figure 4B-C). Furthermore, we used the tamoxifen-inducible RAPTOR–/– (Raptor TAM-iKO) high AR–expressing AML cells by transducing the MLL-AF9 oncogene into bone marrow HSCs isolated from B6.Cg-Rptortm1.1Dmsa/J; ROSA26-CreER female mice (general experimental method described in supplemental Figure 1A-B). In vitro treatment of these cells with 4-hydroxytamoxifen successfully eliminated the expression of RAPTOR and the colony-forming capacity (supplemental Figure 4D-F) of purified Raptor TAM-iKO high AR–expressing AML cells. In addition, in vivo tamoxifen treatment of male and female recipient mice transplanted with primary Raptor TAM-iKO high AR–expressing AML cells significantly prolonged the survival of the recipient mice (Figure 6F). Apart from AKT (Protein kinase B, PKB), other related protein kinases such as the gamma subunits of PKA (Prkacg) and PKC (Prkcg), were also increased in high AR–expressing AML cells (supplemental Figure 5A-B). However, PTEN (Phosphatase and tensin homolog), a well-known tumor suppressor that negatively regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis,25 was upregulated in high AR–expressing AML cells at the mRNA and protein levels. Further analysis showed that PTEN was phosphorylated at Thr382/383, suggesting loss of tumor suppressor activity (supplemental Figure 5C-D).26

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is upregulated to mediate the increased aggressiveness in high AR–expressing AML cells. (A-B) Expression of (A) the PI3K gene (Pik3ca, Pik3cb, and Pik3cd) and (B) the AKT gene (Akt1 and Akt2) assessed by qPCR in low and high AR–expressing AML cells. The data were normalized to low AR–expressing AML cells and Gapdh housekeeping gene (n = 6-10 biologic replicates). (C) Western blot showing the expression of P-PI3K, PI3K, P-AKT, and AKT in low and high AR–expressing AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (D) Western blot showing the expression of P-AKT and AKT in female and male patient–derived AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (E) Western blot showing the expression of P-MTOR, mTOR, P-p70S6K, and p70S6K in low and high AR–expressing AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (F) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in high AR–expressing AML cells treated with 10 μM LY294002, 10 nM wortmannin, 10 μM Akt inhibitor, 10 nM sapanisertib, or 250 nM torin1 for 24 hours; apoptotic cells were identified as the Annexin V+7-AAD–population. All data were normalized to and compared with vehicle treatment. (G) The survival curve of 2° male and female recipients transplanted with 1° Raptor TAM-iKO high AR–expressing AML cells. The mice were treated with tamoxifen (75 mg/kg per day in 100 μL corn oil, intraperitoneal injection for 5 days) at 1 week after transplantation and followed up for 60 days; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by the log-rank test. (H) Schematic illustration of the mechanism of action of finasteride and ARN509. Panels A-B, F, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of the replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. TME, tumor microenvironment.

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is upregulated to mediate the increased aggressiveness in high AR–expressing AML cells. (A-B) Expression of (A) the PI3K gene (Pik3ca, Pik3cb, and Pik3cd) and (B) the AKT gene (Akt1 and Akt2) assessed by qPCR in low and high AR–expressing AML cells. The data were normalized to low AR–expressing AML cells and Gapdh housekeeping gene (n = 6-10 biologic replicates). (C) Western blot showing the expression of P-PI3K, PI3K, P-AKT, and AKT in low and high AR–expressing AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (D) Western blot showing the expression of P-AKT and AKT in female and male patient–derived AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (E) Western blot showing the expression of P-MTOR, mTOR, P-p70S6K, and p70S6K in low and high AR–expressing AML cells. Each lane represents 1 biologic replicate. (F) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in high AR–expressing AML cells treated with 10 μM LY294002, 10 nM wortmannin, 10 μM Akt inhibitor, 10 nM sapanisertib, or 250 nM torin1 for 24 hours; apoptotic cells were identified as the Annexin V+7-AAD–population. All data were normalized to and compared with vehicle treatment. (G) The survival curve of 2° male and female recipients transplanted with 1° Raptor TAM-iKO high AR–expressing AML cells. The mice were treated with tamoxifen (75 mg/kg per day in 100 μL corn oil, intraperitoneal injection for 5 days) at 1 week after transplantation and followed up for 60 days; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by the log-rank test. (H) Schematic illustration of the mechanism of action of finasteride and ARN509. Panels A-B, F, error bars represent the mean ± SEM of the replicates. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01, as determined by a 1-tailed unpaired Student t test. TME, tumor microenvironment.

Transcriptomic analysis also indicated significant upregulation of EPHA7, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) involved in bidirectional signaling through ephrin ligands (eg, ephrin-A5) to regulate proliferation, survival, and differentiation through SRC, among other pathways,27 and the downstream adaptor protein GAB2 in high AR–expressing AML cells (female) when compared with low AR–expressing AML cells (male; supplemental Figure 5E). As an adaptor for RTKs, GAB2 not only activates PI3K and AKT but also other downstream signaling pathways.28 Consistent with that role, we detected significantly increased expression of total SRC, P-SRC (Tyr416), and HIF-1α (supplemental Figure 5F). In summary, our data indicate that the RTK-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR and SRC/HIF-1α signaling pathways contribute to the increased aggressiveness of the high AR–expressing AML cells.

Finally, we sought to explain the interplay between AR and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and SRC/HIF-1α signaling pathways in the context of leukemogenesis. Inhibition of the ARs by ARN509 had no effect on the expression of Pi3k and Akt1 (supplemental Figure 6A-B) but led to decreased levels of Akt2 and Pka (supplemental Figure 6C-D) at doses of 100 and 150 nM. Even though ARN509 had no effect on the phosphorylation of P70S6K in high AR-expressing AML cells (supplemental Figure 6E-F), there was a decrease in the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 (supplemental Figure 6G-H). These data suggest that AR signaling partially regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis. Analysis of Raptor TAM-iKO high AR–expressing AML cells isolated from the whole spleen of tamoxifen- or vehicle-treated male recipients at the end point (as in Figure 4K) showed that blocking mTORC1-dependent signaling, as demonstrated by decreased P-P70S6K (supplemental Figure 6I), led to decreased levels of AR protein expression (supplemental Figure 6J). We also observed decreased AKT and P-AKT in tamoxifen-treated samples, suggesting a feedback mechanism through the downregulation of ARs (supplemental Figure 6K). These data are consistent with reciprocal regulation of AR signaling and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis to promote the aggressiveness and exacerbation of AML.

Discussion

Our study revealed that AR signaling promotes leukemia progression in MLL-AF9 AML and PDX models via ligand-dependent and -independent mechanisms. In males, high DHT drove AML despite low AR expression in LICs, whereas in females, the effect of low DHT was compensated for by high AR expression. Finasteride improved disease by inhibiting DHT (ligand-dependent), and ARN509 targeted ligand-independent AR activity. The RTK/GAB2, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and SRC/HIF-1α pathways were activated in high AR–expressing cells (Figure 6G), and AR antagonism or attenuated mTORC1 activity reciprocally affected these pathways, suggesting that the interplay is critical for AML progression. Increased AR expression was associated with elevated EPHA7, a gene upregulated in acute leukemias,29 although its role in leukemogenesis remains unclear. Eph receptors signal through RAS-MAPK, whereas reverse ephrin signaling engages SRC,27 consistent with our findings. A phase 1 trial that targeted EPHA3, which is also elevated in AML and myelodysplastic syndrome, was well tolerated but not pursued further.30 Our findings suggest a potential link between AR signaling and EPHA7 activation in AML. Although androgen/AR signaling is well-studied in prostate cancer and has successfully guided molecular-targeted therapies,31,32 its role in AML remains underexplored. Some early studies suggest that increased androgen/AR signaling may exacerbate esophageal cancer, glioblastoma, and kidney cancer while potentially exerting beneficial effects in colorectal cancer.33-37 These findings underscore the need for further investigation into the context-dependent role of AR-signaling in cancer. Notably, male patients with a history of testicular cancer exhibited higher susceptibility to acute lymphoid leukemia and AML,38 suggesting that reduced androgen levels or androgen deprivation may influence leukemogenesis and hold therapeutic potential in AML. Given DHT’s higher affinity for AR when compared with testosterone, inhibiting 5α-reductase with approved drugs like finasteride and dutasteride presents a viable therapeutic strategy.39,40 In this study, finasteride effectively suppressed AML progression in both male and female mice, highlighting its potential for repurposing with minimal translational barriers.

We also observed distinct AR expression patterns in female vs male AML cells in mice. This disparity likely stems from tumor-specific mechanisms rather than inherent sex-based genetic differences, because normal bone marrow cells (including HSCs) did not show a sex-based difference in AR expression. The elevated ARs in female AML cells may be a compensatory response to lower androgen levels in the female tumor microenvironment, mimicking mechanisms seen in prostate cancer in which the AR level is upregulated in response to androgen deprivation.40 Furthermore, our study employed MLL-AF9 fusion-induced AML, which is known to target genes associated with specific histone markers, such as H3K79me2, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac.41 Healthy male and female subjects show similar baseline AR expression in bone marrow.42 However, it is possible that the MLL-AF9 fusion protein may induce AR expression more strongly in females by altering the epigenetic landscape on both X chromosomes.

Unlike animal studies in which the donor and recipient sex can be precisely controlled, clinical data are confounded by cellular heterogeneity, molecular cytogenetic differences, and variability in mRNA and protein expression. For example, TCGA analyses show discordant associations between AR mRNA/protein levels and survival across several cancers, including adrenocortical carcinoma, glioma, stomach adenocarcinoma, and melanoma.15 However, similar data are lacking for AML because of the absence of AR protein expression profiles.15 Given our observations of inconsistent AR mRNA and protein levels in patient-derived AML cells, further investigation into AR protein expression and its impact on AML survival is warranted.

Finasteride, which currently has United States Food and Drug Administration approval for use in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (Proscar) or androgenetic alopecia (Propecia), showed therapeutic benefits in both male and female leukemic mice, supporting its clinical repurposing. Similarly, ARN509, approved in 2018 for nonmetastatic-castration resistant prostate cancer,43,44 reduced high AR–expressing AML cells in MLL-AF9 and PDX models engrafted with patient-derived AML cells, supporting its potential use in future trials to treat AML. Although AR protein expression may differ less distinctly between human sexes than in mice, screening for AR, mTORC, RAPTOR, and p70S6K expression in AML cells may guide patient selection for this therapy. In conclusion, androgen/AR signaling plays a critical role in AML, supporting the rationale for repurposing finasteride and ARN509, pending validation through retrospective and prospective studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank current and previous personnel at the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences for cell sorting (RRID:SCR-024460), and those in Prabhu and Paulson laboratories for timely help. The authors also acknowledge the contributions made by their colleagues from the Animal Resource Program.

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the American Institute for Cancer Research, the College of Agricultural Sciences, the Penn State University, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health R01 DK077152, the United States Department of Agriculture-National Institute for Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) Hatch project (number PEN04932; accession number 70065855; [K.S.P.]), and the USDA-NIFA Hatch project (number PEN04960; accession number 7006577; [R.F.P.]).

Authorship

Contribution: F.Q. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the original draft; D.S., B.E.A., V.M.P., Y.B., B.R., and B.J. performed experiments; H.Z. performed experiments and edited the manuscript; and K.S.P. and R.F.P. designed experiments, supervised the research, acquired funding, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.Q., R.F.P., and K.S.P. have a pending US patent application (63/332943) that describes the use of androgen receptor inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia treatment. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: K. Sandeep Prabhu, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, 108 K Animal & Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences (AVBS) Building, University Park, PA 16802; email: ksp4@psu.edu; and Robert F. Paulson, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, 203 Animal & Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Building, University Park, PA 16802; email: rfp5@psu.edu.

References

Author notes

F.Q. and D.S. contributed equally to this study.

All data in the manuscript or the supplementary materials are available on request from the corresponding authors, K. Sandeep Prabhu (ksp4@psu.edu) or Robert F. Paulson (rfp5@psu.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.