Key Points

No benefit of RIST with standard salvage chemotherapy before alloHCT for poorly responsive AML or first untreated relapse.

AML genetics, not remission status, determine overall survival after alloHCT.

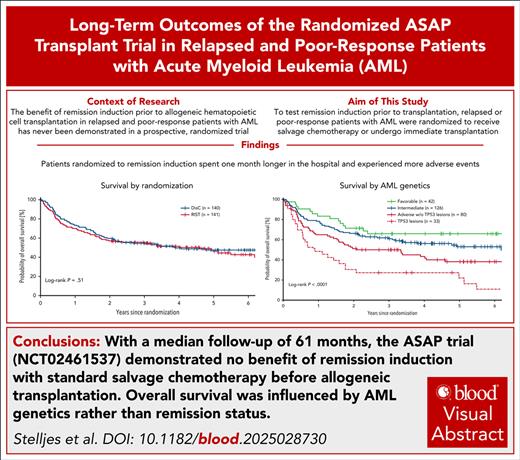

Visual Abstract

Attempting to induce a complete remission before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) is current practice in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, benefit of remission induction strategy (RIST) before alloHCT has never been proven in a prospective trial. Potent conditioning regimens exist that allow for successful alloHCT in patients with active AML. Therefore, the ASAP trial was conducted to test RIST by salvage chemotherapy before alloHCT against immediate transplant after intensified conditioning. In total, 281 patients with AML with poor response after first induction or untreated first relapse were randomized 1:1 to RIST with high-dose cytarabine plus mitoxantrone vs immediate alloHCT with sequential conditioning after nonintensive disease control (DisC) measures, preferentially watchful waiting only. Overall survival at 5 years from randomization analyzed according to intention-to-treat was 46.1% for DisC vs 47.5% for RIST (P = .82). In multivariable Cox regression analysis, genetic AML risk according to European LeukemiaNet criteria (P < .0001), age (P = .001), and comorbidities (P = .046) predicted survival, but not treatment arm (hazard ratio, 1.08 for DisC vs RIST; P = .67). In conclusion, long-term follow-up of the ASAP trial showed no survival advantage for standard salvage chemotherapy before alloHCT as opposed to immediate alloHCT. The trial results question the general concept of RIST with intensive standard salvage therapy before alloHCT for all patients, because immediate alloHCT may reduce time in hospital and health care expenses. Novel bridging therapies that are well tolerated, and posttransplant maintenance with targeted drugs are urgently warranted, especially for adverse-risk AML, to improve outcomes after alloHCT. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT02461537.

Introduction

Selecting patients for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) and bridging them optimally to transplant are subjects of intensive debate. For patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), current practice is to administer induction or salvage chemotherapy, with the aim that patients proceed to alloHCT in complete remission (CR).1 This approach is based on the concept that alloHCT is more efficacious if the number of residual leukemic cells is lower. No formal proof of this concept exists, especially not from prospective clinical trials.

The ASAP trial was the first randomized controlled trial that challenged the standard of remission induction strategy (RIST) before alloHCT.2 In this trial, patients with ≥5% marrow blasts after a first course of standard induction chemotherapy, and patients with untreated first morphological relapse were randomized between disease control (DisC) measures and RIST before transplant. Treatment success was nominally 3.4% higher with DisC compared with RIST. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for treatment success ranged from 12.6% higher success rate with DisC to 5.8% lower success rate with DisC compared with RIST. Consequentially, noninferiority could not be demonstrated formally with a 5% noninferiority margin, and immediate transplant could not be established as a standard comparable to RIST. However, immediate transplant is considered more often today, and innovative highly efficacious sequential conditioning regimens are being further explored.3-6

Here, we report the results of the long-term follow-up of the ASAP trial, updated risk classification according to European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 criteria, risk factor analyses, and the effect of study treatment in defined genetic subgroups.

Methods

Design

The ASAP trial was a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial that evaluated the role of salvage chemotherapy intended to induce CR before alloHCT (ClinicaTrials.gov identifier: NCT02461537). The institutional review board of TU Dresden (IRB00001473) and the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices approved the trial. All patients gave written informed consent. The trial was conducted according to the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

We enrolled patients aged between 18 and 75 years with either first untreated relapse of AML or poorly responsive AML, as defined by ≥5% marrow blasts after the first course of standard induction chemotherapy in the context of non–favorable-risk genetics according to ELN 2010.7 Patients with poor response after cytarabine at doses >1 g/m2 were not eligible. Availability of an HLA compatible related or unrelated donor (≥9/10 allele matched for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1) had to be ensured at randomization, either by confirmatory typing or by >90% probability for 2 compatible unrelated donors. Patients with white blood cell counts >50 × 109/L, central nervous system manifestations, or a history of alloHCT were excluded, as were those with a cumulative exposure to >440 mg/m2 daunorubicin equivalents, a left ventricular ejection fraction of <50%, need for oxygen supplementation, bilirubin >1.5× upper limit of normal, or a glomerular filtration rate <50 mL/min.

Study treatment

Patients were randomized 1:1 to RIST or DisC before alloHCT. Stratification factors were disease status (poor response vs first untreated relapse), age (≤60 years vs >60 years), and disease risk (high risk vs any other, referring to the ELN 2010 risk classification).7 In the DisC arm, patients proceeded to alloHCT as soon as possible (ASAP trial). Preferentially, patients were observed only; however, patients were allowed to receive low-dose cytarabine or single doses of mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2 as DisC measures. Once transplant was organized, patients were scheduled for intensified sequential conditioning with fludarabine-modulated cytarabine and amsacrine (FLAMSA), or high-dose melphalan followed by total body irradiation or alkylator-based reduced-intensity conditioning.8-10 Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis was based on antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

In the RIST arm, salvage chemotherapy consisted of high-dose cytarabine 3 g/m2 (1 g/m2 for patients aged >60 years or with significant comorbidities) twice daily on days 1 to 3, and mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2 on days 3 to 5. After hematopoietic recovery and remission assessment, conditioning intensity was tailored to the level of residual disease and patients’ condition. For details, we refer to the first publication of the trial.2

Definitions

At randomization, AML risk was stratified per-protocol (PP) according to ELN 2010 criteria.7 To refine risk baseline assessment, we switched to ELN 2022 criteria for the statistical analysis.1 When information on the gene panel recommended by ELN 2022 was not available, we reanalyzed diagnostic samples with a comprehensive next-generation sequencing-based assay. All now available cytogenetic and molecular information was reclassified according to ELN 2022 and used for univariable and multivariable risk factor analyses.

Statistical analysis

The primary end point of this intention-to-transplant study was treatment success, defined as documented CR on day 56 after alloHCT. Results for the primary end point have been reported previously.2 In this study, we report long-term outcome data and the results of exploratory subgroup analyses using the same criteria for noninferiority (noninferiority margin of 5% and a 1-sided type I error of 2.5%). Overall survival (OS) from randomization was prespecified as a major secondary end point. Late analysis of survival data with a minimum follow-up of 2 years from randomization of the last patient was specified in the trial protocol. Results of this follow-up analysis are presented here.

Probabilities for time-dependent events were calculated according to Kaplan-Meier and analyzed with the log-rank test in univariate comparisons. Incidences of events were estimated with cumulative incidence statistics, considering death as competing event. Univariate comparisons of cumulative incidences were calculated with the Gray test. Multivariable Cox regression models were fitted, including patient age, sex, AML type, and ELN 2022 risk as covariables. Cox models for end points with randomization as time 0 included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and HCT-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) at randomization, whereas Cox models with transplant as time 0 included ECOG and HCT-CI at admission for transplant and donor type as additional covariables.

Events for GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS) were death, morphological relapse, occurrence of acute GVHD grades 3 to 4, or severe chronic GVHD (cGVHD). The impact of the occurrence of cGVHD on relapse-free survival (RFS), and the risk of relapse and nonreplapse mortality (NRM) was tested in extended Cox regression models with a time-dependent covariable. In multivariable cause-specific Cox models, the risk factor cGVHD was treated as a dichotomous time-dependent variable that switched from 0 to 1 when a certain severity level of cGVHD occurred.

No adjustment for multiple testing was done for the exploratory analyses, including subgroup analyses, reported in this article. All point estimates are reported, together with 95% CIs. We used R (version 4.4.1) for the statistical analysis.

Results

Between September 2015 and January 2022, 281 patients were randomized between DisC and RIST and constitute the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Including extended follow-up, 269 patients (96%) proceeded to alloHCT. In the DisC arm, 137 patients (137/140 [98%]) underwent transplant after a median time of 4.4 weeks from randomization (interquartile range [IQR], 3.6-6.0 weeks). In the RIST arm, 132 patients (132/141 [94%]) underwent transplant after a median of 7.9 weeks (IQR, 7.0-9.3 weeks). Numbers for the PP population were 135 patients who underwent transplant in the DisC arm, and 128 patients who underwent transplant in the RIST arm (see modified CONSORT diagram provided as supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website).

For stratification at randomization, AML risk was classified according to the ELN 2010 criteria. Thus, information on adverse-risk mutations in TP53, ASXL1, RUNX1, and secondary-type AML genes was not considered for randomization. To have information on the entire ELN 2022 gene panel of adverse-risk mutations available, diagnostic samples were reanalyzed. Together with data from extended typing profiles retrieved from medical charts, the risk classification of 248 patients was re-evaluated. Post hoc classification of the additional genetic information according to ELN 2022 resulted in changes of risk assignment for 63 patients. Updated risk assessment showed that more patients with adverse-risk AML were randomized to the DisC arm (48% vs 33%; χ2 test, P = .013), including more than twice as many patients with TP53 abnormalities (16% vs 7%; χ2 test, P = .025). We show updated patient characteristics of the ITT population in Table 1, and split by disease status at enrollment (poor response after first induction vs untreated first relapse) in supplemental Table 1.

Patient characteristics at randomization

| . | DisC (n = 140) . | RIST (n = 141) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR; range), years | 61 (50-66; 18-75) | 61 (54-65; 19-74) | .73 |

| Sex, n (%) | .77 | ||

| Female | 64 (46) | 61 (43) | |

| Male | 76 (54) | 80 (57) | |

| ECOG, n (%) | .69 | ||

| 0-1 | 123 (88) | 127 (90) | |

| 2 | 17 (12) | 14 (10) | |

| HCT-CI, median (IQR; range) | 2 (0-3; 0-10) | 1 (0-3; 0-8) | .30 |

| BM blasts, median (IQR; range), % | 30 (15-50; 2-95) | 30 (18-50; 0-90) | .42 |

| AML type, n (%) | .25 | ||

| De novo | 110 (79) | 102 (72) | |

| sAML | 22 (16) | 33 (23) | |

| tAML | 8 (6) | 6 (4) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | .87 | ||

| Poor response | 90 (64) | 93 (66) | |

| Relapse | 50 (36) | 48 (34) | |

| ELN 2022 (reclassified), n (%) | .014 | ||

| Favorable | 22 (16) | 20 (14) | |

| Intermediate | 51 (36) | 75 (53) | |

| Adverse | 67 (48) | 46 (33) | |

| Genetic abnormalities, n (%) | |||

| t(8;21)(q22;q22.1)/RUNX1::RUNX1T1∗ | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 1.0 |

| inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22)/CBFB::MYH11† | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | .71 |

| bZIP in-frame–mutated CEBPA | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.0 |

| Mutated NPM1 without FLT3-ITD‡ | 14 (10) | 13 (9) | .98 |

| Mutated NPM1 | 22 (16) | 25 (18) | .77 |

| FLT3-ITD | 24 (17) | 21 (15) | .72 |

| t(6;9)(p23.3;q34.1)/DEK::NUP214 | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | .13 |

| t(v;11q23.3)/KMT2A-rearranged, excluding KMT2A-PTD | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | .67 |

| inv(3)(q21.3q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21.3;q26.2)/GATA2, MECOM(EVI1) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 1.0 |

| t(3q26.2;v)/MECOM(EVI1)-rearranged | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.0 |

| Secondary-type mutations§ | 22 (16) | 22 (16) | 1.0 |

| Complex karyotype | 34 (24) | 16 (11) | .007 |

| abn(17p) or TP53mut | 23 (16) | 10 (7) | .025 |

| . | DisC (n = 140) . | RIST (n = 141) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR; range), years | 61 (50-66; 18-75) | 61 (54-65; 19-74) | .73 |

| Sex, n (%) | .77 | ||

| Female | 64 (46) | 61 (43) | |

| Male | 76 (54) | 80 (57) | |

| ECOG, n (%) | .69 | ||

| 0-1 | 123 (88) | 127 (90) | |

| 2 | 17 (12) | 14 (10) | |

| HCT-CI, median (IQR; range) | 2 (0-3; 0-10) | 1 (0-3; 0-8) | .30 |

| BM blasts, median (IQR; range), % | 30 (15-50; 2-95) | 30 (18-50; 0-90) | .42 |

| AML type, n (%) | .25 | ||

| De novo | 110 (79) | 102 (72) | |

| sAML | 22 (16) | 33 (23) | |

| tAML | 8 (6) | 6 (4) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | .87 | ||

| Poor response | 90 (64) | 93 (66) | |

| Relapse | 50 (36) | 48 (34) | |

| ELN 2022 (reclassified), n (%) | .014 | ||

| Favorable | 22 (16) | 20 (14) | |

| Intermediate | 51 (36) | 75 (53) | |

| Adverse | 67 (48) | 46 (33) | |

| Genetic abnormalities, n (%) | |||

| t(8;21)(q22;q22.1)/RUNX1::RUNX1T1∗ | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 1.0 |

| inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22)/CBFB::MYH11† | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | .71 |

| bZIP in-frame–mutated CEBPA | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.0 |

| Mutated NPM1 without FLT3-ITD‡ | 14 (10) | 13 (9) | .98 |

| Mutated NPM1 | 22 (16) | 25 (18) | .77 |

| FLT3-ITD | 24 (17) | 21 (15) | .72 |

| t(6;9)(p23.3;q34.1)/DEK::NUP214 | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | .13 |

| t(v;11q23.3)/KMT2A-rearranged, excluding KMT2A-PTD | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | .67 |

| inv(3)(q21.3q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21.3;q26.2)/GATA2, MECOM(EVI1) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 1.0 |

| t(3q26.2;v)/MECOM(EVI1)-rearranged | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.0 |

| Secondary-type mutations§ | 22 (16) | 22 (16) | 1.0 |

| Complex karyotype | 34 (24) | 16 (11) | .007 |

| abn(17p) or TP53mut | 23 (16) | 10 (7) | .025 |

abn, chromosome abnormalities; BM, bone marrow; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML.

Three patients had adverse ELN 2022: 1 patient with DisC due to complex karyotype, 1 patient with RIST due to del(5q), and 1 patient with RIST due to del(7).

One patient with DisC had adverse ELN 2022 due to a complex and monosomal karyotype and del(7).

Four patients (2 DisC and RIST each) had adverse-risk AML according to ELN 2022 due to complex karyotype.

Secondary-type mutations comprise ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and/or ZRSR2 mutations.

Based on the refined classification of AML risk, we compared post hoc treatment success for subgroups of patients. Results of these exploratory analyses are shown in Table 2. Patients with adverse-risk AML achieved treatment success in 82.1% of cases with DisC and in 69.8% of cases with RIST. This subgroup analysis met the criterion for noninferiority (noninferiority margin of 5%, 1-sided type I error of 2.5%). Further, the criterion for noninferiority for DisC vs RIST was met for patients with mutated NPM1 AML (95.5% with DisC vs 79.2% with RIST) and FLT3-internal tandem duplication (ITD) AML (95.8% with DisC vs 66.7% with RIST). The treatment trajectories for patients with favorable/intermediate AML and for those with adverse-risk AML are displayed by treatment arm in supplemental Figures 2A-B and 3A-B.

Treatment success in genetic subgroups

| Subgroups of PP population . | Treatment success: DisC, % (n/n) . | Treatment success: RIST, % (n/n) . | Difference (%) (95% CI) . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 84.1 (116/138) | 81.3 (109/134) | 2.7 (−6.3 to 11.8) | .047 |

| ELN 2022 | ||||

| Favorable | 95.5 (21/22) | 100.0 (19/19) | −4.5 (−13.7 to 4.6) | .46 |

| Intermediate | 81.6 (40/49) | 83.3 (60/72) | −1.7 (−15.8 to 12.4) | .32 |

| Adverse | 82.1 (55/67) | 69.8 (30/43) | 12.3 (−3.6 to 28.2) | .016 |

| Genetic abnormality | ||||

| Mutated NPM1 | 95.5 (21/22) | 79.2 (19/24) | 16.3 (−4.2 to 36.8) | .021 |

| Mutated NPM1 and FLT3 wild type | 92.9 (13/14) | 83.3 (10/12) | 9.5 (−15.8 to 34.9) | .13 |

| FLT3-ITD | 95.8 (23/24) | 66.7 (14/21) | 29.2 (6.2 to 52.2) | .0018 |

| Secondary-type mutations† | 90.9 (20/22) | 86.4 (19/22) | 4.5 (−14.7 to 23.8) | .17 |

| Complex karyotype | 73.5 (25/34) | 53.3 (8/15) | 20.2 (−7.9 to 48.3) | .039 |

| abn(17p) or TP53 mutations | 73.9 (17/23) | 70.0 (7/10) | 3.9 (−28.4 to 36.2) | .29 |

| Subgroups of PP population . | Treatment success: DisC, % (n/n) . | Treatment success: RIST, % (n/n) . | Difference (%) (95% CI) . | P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 84.1 (116/138) | 81.3 (109/134) | 2.7 (−6.3 to 11.8) | .047 |

| ELN 2022 | ||||

| Favorable | 95.5 (21/22) | 100.0 (19/19) | −4.5 (−13.7 to 4.6) | .46 |

| Intermediate | 81.6 (40/49) | 83.3 (60/72) | −1.7 (−15.8 to 12.4) | .32 |

| Adverse | 82.1 (55/67) | 69.8 (30/43) | 12.3 (−3.6 to 28.2) | .016 |

| Genetic abnormality | ||||

| Mutated NPM1 | 95.5 (21/22) | 79.2 (19/24) | 16.3 (−4.2 to 36.8) | .021 |

| Mutated NPM1 and FLT3 wild type | 92.9 (13/14) | 83.3 (10/12) | 9.5 (−15.8 to 34.9) | .13 |

| FLT3-ITD | 95.8 (23/24) | 66.7 (14/21) | 29.2 (6.2 to 52.2) | .0018 |

| Secondary-type mutations† | 90.9 (20/22) | 86.4 (19/22) | 4.5 (−14.7 to 23.8) | .17 |

| Complex karyotype | 73.5 (25/34) | 53.3 (8/15) | 20.2 (−7.9 to 48.3) | .039 |

| abn(17p) or TP53 mutations | 73.9 (17/23) | 70.0 (7/10) | 3.9 (−28.4 to 36.2) | .29 |

Treatment success was defined as CR on day 56 after alloHCT. The differences in success rates between DisC and RIST have been calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

P values <.025 indicate noninferiority of DisC vs RIST with respect to a noninferiority margin of 5%.

Secondary-type mutations comprise ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and/or ZRSR2 mutations.

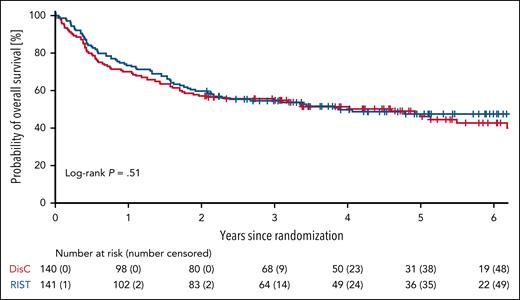

Survival from randomization according to ITT

We locked the database on 12 July 2024 for the long-term follow-up analysis, allowing for a minimum observation period of 2 years since randomization of the last patient. The median follow-up determined by inverted Kaplan-Meier was 61 months (IQR, 44-76). With DisC, 3 of 140 patients died without ever proceeding to alloHCT, compared with 7 of 141 patients with RIST. Analyzed according to ITT, 5-year OS from randomization was 46% (95% CI, 37-55) in the DisC arm compared with 48% (95% CI, 39-56) in the RIST arm (log-rank test, P = .51). OS probabilities of patients randomized to DisC vs RIST are shown as unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves in Figure 1 and as adjusted survival curves in supplemental Figure 4.

OS by study treatment analyzed according to the ITT. OS from randomization analyzed according to the ITT. 5-year OS was 46% (95% CI, 37-55) for patients randomized to DisC vs 48% (95% CI, 39-56) for RIST.

OS by study treatment analyzed according to the ITT. OS from randomization analyzed according to the ITT. 5-year OS was 46% (95% CI, 37-55) for patients randomized to DisC vs 48% (95% CI, 39-56) for RIST.

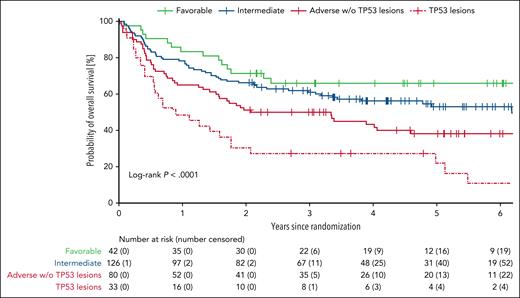

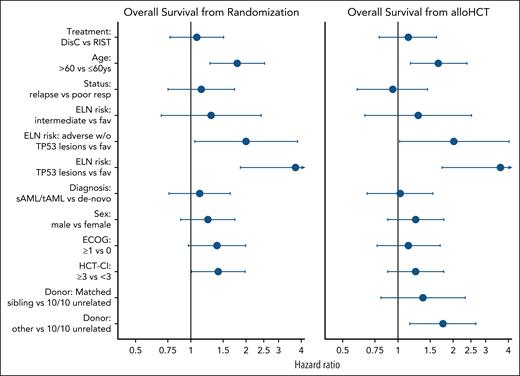

Risk factors at randomization

Besides age, the strongest baseline risk factor in univariable and multivariable Cox regression modeling was AML genetics classified according to ELN 2022 criteria. The 5-year OS from randomization was 66% (95% CI, 49-78) for patients with favorable-risk AML (n = 42), 53% (95% CI, 43-62) for patients with intermediate-risk AML (n = 126), and 34% (95% CI, 25-43) for patients with adverse-risk AML (n = 113; Figure 2). In multivariable Cox regression analysis, patient age (>60 years vs ≤60 years; hazard ratio [HR], 1.78; 95% CI, 1.26-2.51; P = .001) and ELN 2022 risk (adverse risk vs other; HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.38-2.73; P < .0001) predicted OS (Figure 3; supplemental Table 2).

OS from study enrollment by ELN risk. OS from randomization was analyzed for all patients. AML risk was classified according to the ELN 2022 criteria. w/o, without.

OS from study enrollment by ELN risk. OS from randomization was analyzed for all patients. AML risk was classified according to the ELN 2022 criteria. w/o, without.

Risk factor analysis for OS. This figure shows HRs of multivariable Cox regression modeling for OS from randomization in the ITT population (left) and OS from alloHCT in the PP population (right). HRs >1 indicate an increased risk of mortality for the first mentioned subgroup. Dots and whiskers represent the estimated effect estimates for the respective factors together with the corresponding 95% CIs. An upper limit of the CI outside the limits is indicated by an arrow. Exact values are given in supplemental Table 2. fav, favorable; resp, response; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML.

Risk factor analysis for OS. This figure shows HRs of multivariable Cox regression modeling for OS from randomization in the ITT population (left) and OS from alloHCT in the PP population (right). HRs >1 indicate an increased risk of mortality for the first mentioned subgroup. Dots and whiskers represent the estimated effect estimates for the respective factors together with the corresponding 95% CIs. An upper limit of the CI outside the limits is indicated by an arrow. Exact values are given in supplemental Table 2. fav, favorable; resp, response; sAML, secondary AML; tAML, therapy-related AML.

Survival for patient subgroups by randomization

We compared OS by treatment assignment in subgroups of patients to identify baseline characteristics that might inform future treatment recommendations. Probabilities for 3-year OS from randomization are provided for all subgroups in Table 3. OS curves by randomization and AML risk group are displayed in supplemental Figure 5. Survival between the treatment arms differed only for patients, with NPM1 mutation with better 3-year OS for patients randomized to DisC vs RIST. Among patients with adverse-risk AML, patients without TP53 abnormalities showed higher 3-year OS rates compared with patients with TP53 abnormalities across both treatment arms. Patients with TP53 abnormalities had the poorest outcome in the trial, with 3-year OS rates of 26% (95% CI, 11-45) for patients assigned to DisC vs 30% (95% CI, 7-58) for patients assigned to RIST (P = .82).

OS at 3 years from randomization by baseline characteristics and treatment arm

| Subgroups of ITT population . | n (DisC/RIST) . | 3-Year OS probability (95% CI) . | P value∗ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DisC . | RIST . | |||

| All patients | 140/141 | 55 (46-63) | 54 (46-62) | .95 |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤60 | 69/67 | 68 (55-77) | 59 (46-70) | .28 |

| >60 | 71/74 | 42 (31-53) | 51 (39-61) | .32 |

| Disease status | ||||

| Poor response | 90/93 | 49 (38-58) | 54 (43-64) | .45 |

| Relapse | 50/48 | 66 (51-77) | 55 (40-68) | .26 |

| White blood cell count | ||||

| Below median | 64/74 | 54 (41-66) | 56 (44-67) | .85 |

| Median or higher (1.9 × 109/L) | 76/66 | 55 (43-65) | 53 (40-64) | .76 |

| Bone marrow blasts at randomization | ||||

| Below median (30%) | 66/63 | 65 (52-75) | 58 (45-69) | .40 |

| Median or higher | 73/75 | 46 (35-57) | 53 (41-64) | .42 |

| ELN 2022 risk | ||||

| Favorable | 22/20 | 91 (68-98) | 37 (17-59) | <.001 |

| Intermediate | 51/75 | 56 (42-69) | 64 (52-74) | .39 |

| Adverse | 67/46 | 42 (30-53) | 46 (31-59) | .68 |

| Adverse without TP53 abnormalities | 44/36 | 50 (35-64) | 50 (33-65) | 1.0 |

| Adverse with TP53 abnormalities | 23/10 | 26 (11-45) | 30 (7-58) | .82 |

| Genetic abnormality | ||||

| NPM1-mut | 22/25 | 68 (45-83) | 40 (21-58) | .043 |

| FLT3-ITD | 24/21 | 54 (33-71) | 42 (21-62) | .43 |

| Secondary-type mutations | 22/22 | 55 (32-72) | 64 (40-80) | .54 |

| Complex karyotype | 34/16 | 26 (13-42) | 31 (11-54) | .73 |

| abn(17p) or TP53 mutations | 23/10 | 26 (11-45) | 30 (7-58) | .82 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| De novo AML | 110/102 | 59 (49-68) | 55 (45-64) | .54 |

| sAML/tAML | 30/39 | 40 (23-57) | 54 (37-68) | .26 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 64/61 | 56 (43-67) | 58 (44-69) | .88 |

| Male | 76/80 | 54 (42-64) | 52 (41-63) | .88 |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0 | 59/47 | 68 (54-78) | 66 (50-78) | .85 |

| 1-2 | 81/94 | 45 (34-56) | 49 (38-58) | .68 |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| <3 | 83/91 | 62 (51-72) | 58 (47-67) | .52 |

| ≥3 | 57/50 | 44 (31-56) | 49 (34-62) | .61 |

| Subgroups of ITT population . | n (DisC/RIST) . | 3-Year OS probability (95% CI) . | P value∗ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DisC . | RIST . | |||

| All patients | 140/141 | 55 (46-63) | 54 (46-62) | .95 |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤60 | 69/67 | 68 (55-77) | 59 (46-70) | .28 |

| >60 | 71/74 | 42 (31-53) | 51 (39-61) | .32 |

| Disease status | ||||

| Poor response | 90/93 | 49 (38-58) | 54 (43-64) | .45 |

| Relapse | 50/48 | 66 (51-77) | 55 (40-68) | .26 |

| White blood cell count | ||||

| Below median | 64/74 | 54 (41-66) | 56 (44-67) | .85 |

| Median or higher (1.9 × 109/L) | 76/66 | 55 (43-65) | 53 (40-64) | .76 |

| Bone marrow blasts at randomization | ||||

| Below median (30%) | 66/63 | 65 (52-75) | 58 (45-69) | .40 |

| Median or higher | 73/75 | 46 (35-57) | 53 (41-64) | .42 |

| ELN 2022 risk | ||||

| Favorable | 22/20 | 91 (68-98) | 37 (17-59) | <.001 |

| Intermediate | 51/75 | 56 (42-69) | 64 (52-74) | .39 |

| Adverse | 67/46 | 42 (30-53) | 46 (31-59) | .68 |

| Adverse without TP53 abnormalities | 44/36 | 50 (35-64) | 50 (33-65) | 1.0 |

| Adverse with TP53 abnormalities | 23/10 | 26 (11-45) | 30 (7-58) | .82 |

| Genetic abnormality | ||||

| NPM1-mut | 22/25 | 68 (45-83) | 40 (21-58) | .043 |

| FLT3-ITD | 24/21 | 54 (33-71) | 42 (21-62) | .43 |

| Secondary-type mutations | 22/22 | 55 (32-72) | 64 (40-80) | .54 |

| Complex karyotype | 34/16 | 26 (13-42) | 31 (11-54) | .73 |

| abn(17p) or TP53 mutations | 23/10 | 26 (11-45) | 30 (7-58) | .82 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| De novo AML | 110/102 | 59 (49-68) | 55 (45-64) | .54 |

| sAML/tAML | 30/39 | 40 (23-57) | 54 (37-68) | .26 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 64/61 | 56 (43-67) | 58 (44-69) | .88 |

| Male | 76/80 | 54 (42-64) | 52 (41-63) | .88 |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0 | 59/47 | 68 (54-78) | 66 (50-78) | .85 |

| 1-2 | 81/94 | 45 (34-56) | 49 (38-58) | .68 |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| <3 | 83/91 | 62 (51-72) | 58 (47-67) | .52 |

| ≥3 | 57/50 | 44 (31-56) | 49 (34-62) | .61 |

DisC, disease control strategy; RIST, remission induction strategy; ELN, European Leukemia Network 2022 classification1; sAML, secondary acute myeloid leukemia; tAML, therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia; ECOG, Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group Performance status; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation – comorbidity index11,12; BM, bone marrow; alloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; 95%-CI, 95% confidence interval.

P value of z test.

Analyses with transplant as time 0

The PP population consisted of 272 patients. We performed an additional series of analyses for PP-treated patients in the DisC arm (n = 135) and the RIST arm (n = 128) who proceeded to alloHCT. Three-year OS from alloHCT was 55% (95% CI, 47-63) with DisC vs 55% (95% CI, 46-63) with RIST (P = .97). Three-year event-free survival was 43% (95% CI, 35-51) with DisC vs 48% (95% CI, 39-56) with RIST (P = .48). The cumulative incidences of NRM and relapse/progression at 3 years were 18% (95% CI, 11-24) and 39% (95% CI, 31-47) with DisC vs 17% (95% CI, 10-23) and 36% (95% CI, 28-44) with RIST. Causes of death between day 56 and 1 year after alloHCT showed no major differences (supplemental Table 3). GRFS at 3 years after transplant was 34% (95% CI, 26-42) in the DisC arm and 38% (95% CI, 30-46) in the RIST arm (log-rank test, P = .56). The incidences of acute GVHD grades 2 to 4 at day 120 were 21% (95% CI, 15-28) with DisC vs 20% with RIST (95% CI, 13-27; P = .82). cGVDH of any severity was observed more frequently in the RIST arm (43% [95% CI, 34-52]) compared with the DisC arm (26% [95% CI, 19-33]; Gray test, P = .004). The 1-year cumulative incidences of moderate/severe cGVHD and severe cGVHD were 17% (95% CI, 11-23) and 5% (95% CI, 1-9), respectively in the DisC arm, vs 26% (95% CI, 18-33) and 9% (95% CI, 4-14), respectively, in the RIST arm (Gray test, P = .08 for moderate/severe cGVHD, and P = .06 for severe GVHD).

In multivariable Cox regression analysis of OS from alloHCT, patient age >60 years (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.16-2.36; P = .005) and adverse ELN 2022 risk (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.35-2.79; P < .0001) predicted OS (Figure 3; supplemental Table 2). Neither updated ECOG performance status nor HCT-CI before alloHCT predicted OS. Patients with 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donors showed the best OS (HLA-identical sibling vs 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donors [HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 0.82-2.33; P = .23]; 9/10 partially HLA-matched unrelated or haploidentical donors vs 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated [HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.16-2.67; P = .007]).

Was achieving CR before alloHCT beneficial?

Of the 135 patients randomly assigned to DisC who proceeded to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, 97 (69%) patients underwent watchful waiting only, and 38 (27%) patients underwent antileukemic treatment (ie, low-dose cytarabine or single doses of mitoxantrone). The need for antileukemic treatment before alloHCT was a negative risk factor for survival (supplemental Figure 2C). In the DisC arm, 3-year OS after alloHCT was 62% (95% CI, 51-71) with watchful waiting before alloHCT (97/135 [72%]), vs 39% (95% CI, 24-54) if antileukemic therapy was administered (log-rank test, P = .034). In the RIST arm, remission status at alloHCT was a significant posttransplant risk factor (supplemental Figure 3C). Three-year OS after alloHCT was 62% (95% CI, 49-73) for patients achieving CR after salvage chemotherapy (65/128 [51%]) vs 48% (95% CI, 35-59) for patients with refractory AML (log-rank test, P = .029). Moreover, patients with minimal residual disease–negative CR showed nominally a lower risk of relapse (Gray test, P = .21) and improved survival (log-rank test, P = .15) compared with patients with minimal residual disease–positive CR (supplemental Figure 6).

To analyze whether patients had a benefit from achieving a CR before alloHCT, we analyzed survival stratified according to ELN 2022 risk. For patients with favorable/intermediate AML, 3-year OS after alloHCT was 77% (95% CI, 63-87) with watchful waiting in the DisC arm (n = 49) vs 66% (95% CI, 51-78) for patients who underwent transplant with CR in the RIST arm (n = 49; Figure 4A). For patients with adverse-risk AML, 3-year OS was 46% (95% CI, 31-59) with watchful waiting in the DisC arm (n = 48) vs 50% (95% CI, 25-71) for patients who underwent transplant with CR in the RIST arm (n = 16; Figure 4B).

OS after transplant by treatment and remission status. This figure shows survival after transplant for patients in the DisC or RIST arm. AML risk was stratified according to ELN 2022 into favorable or intermediate (A) and adverse (B). Outcome is displayed by treatment status at the time of transplant. The survival curves represent 4 groups of patients: patients with watchful waiting only (DisC arm), patients with chemotherapy for DisC (DisC arm), patients with a CR after salvage chemotherapy (RIST arm), and patients without CR after salvage chemotherapy (RIST arm).

OS after transplant by treatment and remission status. This figure shows survival after transplant for patients in the DisC or RIST arm. AML risk was stratified according to ELN 2022 into favorable or intermediate (A) and adverse (B). Outcome is displayed by treatment status at the time of transplant. The survival curves represent 4 groups of patients: patients with watchful waiting only (DisC arm), patients with chemotherapy for DisC (DisC arm), patients with a CR after salvage chemotherapy (RIST arm), and patients without CR after salvage chemotherapy (RIST arm).

Results after alloHCT of the corresponding poor-risk groups, those who needed antileukemic treatment in the DisC arm before alloHCT, and those who failed to achieve CR in the RIST arm were also not significantly different for patients (Figure 3).

No significant impact of marrow blast count before conditioning for successful alloHCT

To address the question, if a maximum tolerable marrow blast count exists for successful alloHCT, we analyzed the impact of the marrow blast count before start of conditioning among patients with active AML in the DisC arm. To this end, we grouped patients according to their marrow blast counts and the presence of extramedullary AML into 4 categories and fitted multivariable Cox regression models for OS. With 5% to 20% marrow blasts or <5% marrow blasts but extramedullary AML as reference category (n = 40), the HRs were 0.43 (95% CI, 0.16-1.15; P = .09), for patients with <5% marrow blasts (n = 16), 1.00 (95% CI, 0.52-1.95; P = .99), for patients with 20% to <50% marrow blasts, and 1.16 (95% CI, 0.60-2.23; P = .66), for patients with ≥50% marrow blasts.

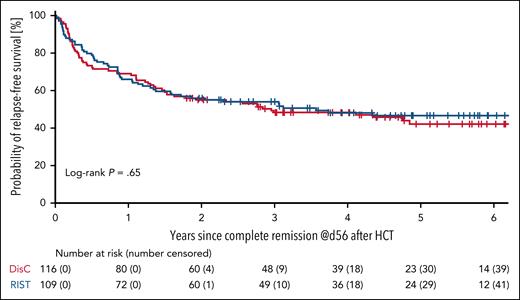

Maintaining remission with treatment success after transplant

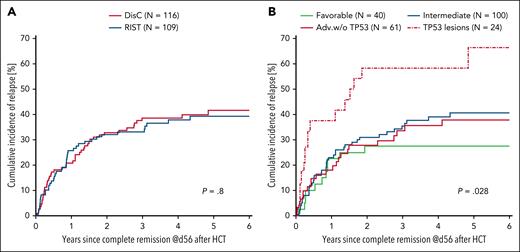

To assess remission quality in the 2 treatment arms, we compared RFS among PP-treated patients randomized to the DisC and RIST arms. The 3-year RFS was 48% (95% CI, 39-57) among 116 patients who achieved CR on day 56 after alloHCT in the DisC arm compared with 54% (95% CI, 44-63) among 109 patients in the RIST arm (P = .40; Figure 5). The 3-year cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM were 39% (95% CI, 30-48) and 13% (95% CI, 7-19), respectively, for patients treated with DisC before HCT, and 33% (95% CI, 24-42) and 13% (95% CI, 6-19) for patients treated according to the RIST strategy (Figure 6A). Discriminated by AML risk, the 3-year cumulative incidences of relapse were 27% (95% CI, 13-42) for patients with favorable-risk genetics, in contrast to 58% (95% CI, 38-79) for patients with TP53 abnormalities (Figure 6B).

RFS. RFS from day 56 after alloHCT is shown for PP-treated patients with treatment success. Treatment success was achieved by 116 of 140 patients (83%) randomized to DisC, and by 109 of 141 patients (77%) randomized to RIST.

RFS. RFS from day 56 after alloHCT is shown for PP-treated patients with treatment success. Treatment success was achieved by 116 of 140 patients (83%) randomized to DisC, and by 109 of 141 patients (77%) randomized to RIST.

Cumulative incidences of relapse by treatment arm and AML risk. Cumulative incidence curves for relapse are shown by treatment arm (A) and AML risk according to ELN 2022 criteria (B) for the PP population with treatment success. Time 0 marks CR assessment on day 56 after transplant. Adv.w/o, adverse ELN 2022 risk without TP53 mutation.

Cumulative incidences of relapse by treatment arm and AML risk. Cumulative incidence curves for relapse are shown by treatment arm (A) and AML risk according to ELN 2022 criteria (B) for the PP population with treatment success. Time 0 marks CR assessment on day 56 after transplant. Adv.w/o, adverse ELN 2022 risk without TP53 mutation.

We found no difference for GRFS by treatment arm (supplemental Figure 7). We tested the impact of cGVHD as a time-dependent event in patients with treatment success. The HR for cGVHD of any grade as a time-dependent event was estimated as 0.77 (95% CI, 0.48-1.23; P = .27), for RFS, 0.65 (95% CI, 0.38-1.11; P = .12), for relapse, and 1.49 (95% CI, 0.57-3.94; P = .42), for NRM. HRs for the impact of moderate or severe cGVHD were 0.88 (95% CI, 0.54-1.44; P = .61), for RFS, 0.56 (95% CI, 0.3-1.05; P = .071), for relapse, and 2.96 (95% CI, 1.16-7.55; P = .023), for NRM.

Discussion

RIST before alloHCT is current practice for patients with AML, albeit no data from prospective clinical trials support this approach.1 Even data from large observational trials starting with diagnosis or relapse as time 0 that display the impact of RIST are lacking. Against this backdrop, patients with poor response after first induction or first untreated morphological relapse were randomized in the ASAP trial to receive either standard salvage chemotherapy with the aim to induce a remission before alloHCT, or DisC and immediate alloHCT after intensified conditioning.2 This trial showed no advantage of RIST for an early surrogate end point, defined as CR on day 56 after alloHCT. This surrogate end point had been selected as primary end point because both alloHCT and CR are necessary conditions for long-term survival. Here, we report mature survival data. OS from randomization analyzed according to the ITT principle showed no advantage for RIST. Despite a disadvantage of the DisC arm due to more patients with adverse-risk AML (especially with TP53-mutant AML), Kaplan-Meier curves for OS were superimposable. The ASAP data, thus, question the value of RIST with conventional salvage chemotherapy before alloHCT for patients with poorly responsive or relapsed AML.

Post hoc analyses show that patients in the RIST arm who had achieved a CR after salvage chemotherapy fared better after transplant. Chemotherapy sensitivity was a significant biomarker for survival chances. However, survival after alloHCT of those patients was comparable to survival of patients in the DisC arm who did not need nonintense chemotherapy while waiting for transplant. Also, patients in the RIST arm who did not achieve CR after salvage chemotherapy showed similar survival compared with patients in the DisC arm who needed nonintense chemotherapy while waiting for transplant (Figure 4). This observation suggests that it is rather interpatient variation of AML biology that determines survival after transplant than the treatment administered for RIST or bridging. The data also support the notion that reduction of leukemia burden per se may not improve survival chances after alloHCT, if highly active regimens are used for conditioning like in the ASAP trial. However, we cannot exclude that distinct AML subgroups differentially benefit from one or the other strategy tested in the ASAP trial. The identification of these subgroups, however, remains a challenge to be addressed in future trials.

Besides the introduction of gilteritinib as a bridge to transplant for patients with relapsed/refractory AML, other potent innovative salvage regimens for patients with AML are being explored.6,13 One approach builds on the combination of classical chemotherapy with venetoclax; promising efficacy and high transition rates to alloHCT were reported with this approach.14-16 A second approach builds on the combination of targeted drugs with venetoclax. FLT3 inhibitors combined with venetoclax and hypomethylating drugs appear to be tolerated well, and may lead to high rates of morphological and molecular CRs in FLT3-mutant AML.17,18 For patients with KMT2A-rearranged or NPM1-mutated relapsed/refractory AML, menin inhibition appears highly attractive.19,20 Although data from large phase 2 or randomized controlled trials are lacking, those approaches are promising.

A major challenge in bridging patients with active AML to alloHCT is the fact that the acceptable level of residual disease with a specific conditioning regimen is poorly defined. No randomized controlled trials inform this question. In the ASAP trial, sequential conditioning was scheduled for patients randomized to the DisC arm, and thus proceeding to alloHCT with active AML. However, superiority of sequential conditioning regimens with FLAMSA or high-dose melphalan over less intensive regimens has not been proven. Further, it should be noted that amsacrine is not approved in all parts of the world, and experience with sequential conditioning regimens is not available everywhere. Possibly, reduced-toxicity conditioning with fludarabine in combination with treosulfan may be sufficient to eliminate residual disease for many patients with ≤20% marrow blasts.21 So far, conditioning intensity is not adapted to AML genetics according to evidence-based rules. However, it is possible that conditioning regimens should be tailored to drug sensitivity of AML to achieve the necessary level of leukemia cell reduction without excessive toxicity. Further randomized controlled trials addressing these questions are highly warranted, especially trials evaluating conditioning regimens for patients with defined levels of measurable residual disease. To this end, a new generation of conditioning regimens is being investigated that may further improve the risk-benefit ratio by adding molecular targeted drugs to standard regimens.5,22

Only patients with favorable-risk AML demonstrated superior OS from randomization with DisC in exploratory analyses. It is possible that superior OS with DisC in this subgroup is an incidental finding. Most patients with favorable-risk AML were enrolled with untreated morphological relapse. Patients with favorable-risk AML usually have chemosensitive disease, and concordantly also showed the highest rate of treatment success in both treatment arms in this study. Relapse and nonrelapse mortality after transplant led to inferior survival in the RIST arm. However, this finding is compatible with the concept that patients with relapsed or refractory AML with favorable-risk genetics benefit from optimal timing of cytoreduction before alloHCT and reduced cumulative exposure to chemotherapy. Notably, excellent outcomes with immediate alloHCT were also reported in 2 independent retrospective studies with patients with favorable-risk AML and untreated molecular relapse.23,24

The uncertain benefit of RIST before alloHCT stands in stark contrast to the fundamental impact of AML genetics. AML biology dictated survival after alloHCT, whereas patients with favorable-risk AML (almost exclusively after having experienced relapse) showed 5-year survival rates of 66%, patients with adverse-risk AML had disappointingly low 5-year survival rates of 34%. Those results are in line with previously published reports on the prognostic impact of the ELN 2022 classification in patients undergoing alloHCT.25 Especially, patients with AML and chromosome 17p abnormalities (abn[17p])/TP53 mutations have an unmet medical need even after alloHCT.26,27 With the results of our study, maintenance therapies or preemptive posttransplant interventions harnessing graft-versus-leukemia reactions appear most promising for this group of patients, whereas further attempts to induce remission before transplant may not solve the problem.

In conclusion, immediate alloHCT after sequential conditioning may reduce time in hospital and exposure to chemotherapy without compromising long-term outcome compared with standard salvage chemotherapy before transplant.2 Innovative bridging concepts with targeted drugs, such as FLT3 inhibitors for patients with FLT3-mutated AML, before alloHCT are warranted for adverse-risk AML, and should be tested in controlled clinical trials to demonstrate a benefit for patients compared with immediate alloHCT. The profound impact of genetic risk on long-term survival signals that patients with poor response or relapsed AML may benefit from maintenance therapy for relapse prevention after alloHCT rather than conventional attempts to induce CR before alloHCT.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the members of the data safety monitoring board, Simona Iacobelli (Rome, Italy), Olivier Tournilhac (Clermont-Ferrand, France), Oliver Ottmann (Cardiff, United Kingdom), and Grzegorz Basak (Warsaw, Poland). Further, the authors thank all administrative staff, study managers, study nurses, and monitoring staff. Above all, the authors are deeply grateful to patients and their caregivers for participating in this trial.

DKMS funded the trial with support from the Gert und Susanna Mayer Stiftung. DKMS sponsored this trial in a legal and financial sense.

Authorship

Contribution: J. Schetelig, M.S., M.B., G.B., C. Schmid, S.W.K., C. Röllig, W.E.B., H.S., G.E., and A.H.S. conceptualized and designed the study; A.H.S., S.T., J.M.M., C. Röllig, and F.S. provided administrative support; M.S., J.M.M., G.B., E.-M.W.-D., L.P.M., C. Schmid, S.W.K., W.B., E.J., U.P., S.A.K., J.N., M.K., K.S.-E., F.S., C. Röllig, M.v.B., K.E.-H., D.K., B.S., B.H., C. Schliemann, K.S., F.L., O.K., J. Schaffrath, C. Reicherts, M.B., J.-H.M., G.E., and J. Schetelig were involved in provision of study materials or patients; S.T. and J. Schetelig collected and assembled the data; S.T., H.B., and J. Schetelig had access to the raw data; H.B. performed the statistical analysis; H.B., M.S., M.B., G.B., J.-H.M., E.-M.W.-D., L.P.M., C. Schmid, C. Röllig, J.M.M., and J. Schetelig analyzed and interpreted the data; J. Schetelig, M.S., J.M.M., M.B., G.B., and J.-H.M. wrote the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript and were accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.S. has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Amgen; has served as a speaker for Pfizer, Medac, MSD, and Incyte; has received research funding from Pfizer; and has received travel support from Medac and Neovii. J.M.M. has served as consultant for Janssen, Roche, Gilead, AbbVie, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Astellas, Novartis, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Glycostem; is a shareholder of Cancilico and Synagen; has received research funding from Servier, Janssen, and Novartis; and has received travel support from BeiGene. G.B. has received honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), and Otsuka; has served as a consultant for Novartis and Gilead Sciences; has received research funding from Novartis; and has received travel support from Gilead Sciences and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. L.P.M. has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Amgen, Gilead Sciences, and Novartis; has received research funding from Amgen; and has received travel support from Gilead Sciences. S.W.K. has received honoraria from Kosmas; has received research funding from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics; and has received travel support from AbbVie, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Alexion Pharmaceuticals. S.A.K. has served as a consultant for Novartis and Pfizer. F.S. has received lecture fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medac, and Pfizer; participated in advisory boards for Glycostem; and has received travel support from Servier, Medac, and Janssen. C. Röllig received honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, Jazz, Janssen, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Servier; and institutional research support from AbbVie, Astellas, Novartis, and Pfizer. K.E.-H. participated in advisory boards for Sanofi and BeiGene; and has received travel support from Servier. D.K. has received honoraria and travel grants from, and has participated in advisory boards for, Jazz Pharmaceuticals; and has received travel support from Medac and Neovii. B.S. has received travel support from AbbVie and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. B.H. has received travel support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Kite (a Gilead company). C. Schliemann has received honoraria from, or served on advisory boards for, AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, BMS, Laboratories Delbert, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Roche; has received institutional research support from Jazz Pharmaceutical; and has received travel support from AbbVie, BMS, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. K.S. received research funding from Active Biotech; has received honoraria from Novartis, BMS/Celgene, and GlaxoSmithKline; and served as a consultant for Novartis, BMS/Celgene, and GlaxoSmithKline. O.K. has received honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Stemline Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology, and Pfizer; and has received travel support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. J. Schaffrath has received travel support from Gilead Sciences and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. C. Reicherts has received travel support from Medac and Gilead Sciences. W.E.B. holds stock and other ownership interests in, has received honoraria and research funding from, and has served as a consultant for, Philogen; holds international patent rights for vascular targeting of tissue factor and short interfering RNA targeting, so far without any return of money; is co-owner and chief executive officer of 2 biotech start-ups, Anturec and Elvesca; has given expert testimony for Philogen; and has received travel and accommodation expenses from Philogen. H.S. holds stock and other ownership interests in Intellia Therapeutics, BioNTech, Arvin, and Kymera; has received honoraria from Novartis, Robert-Bosch-Gesellschaft für Medizinische Forschung mbH, and Gilead Sciences; has served as a consultant for Gilead Sciences, Institut für Klinische Pharmakologie Stuttgart, and AbbVie; and holds patent and other intellectual properties on Samhd1 modulation for treating resistance to cancer therapy, oncogene redirection, companion diagnostics for leukemia treatment, and markers for responsiveness to an inhibitor of FLT3. M.B. received honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and MSD Oncology; and has received travel support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals. J. Schetelig participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca, BMS, Janssen, MSD, and Sanofi; and received lecture fees from Astellas, Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Eurocept, Medac, and Janssen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of all investigators of the ASAP trial, the members of the German Cooperative Study Group and the steering group of the Study Alliance Leukemia appears in the supplemental Appendix.

Correspondence: Johannes Schetelig, Department of Internal Medicine I, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, TU Dresden, Fetscherstr 74, 01307 Dresden, Germany; email: johannes.schetelig@ukdd.de.

References

Author notes

M.S., J.M.M., G.B., M.B., and J. Schetelig contributed equally to this study.

Presented orally at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024.

The study protocol and associated documents (informed consent forms, statistical analysis plan, safety manual, risk management plan, and monitoring plan) are available on request from the correspoonding author, Johannes Schetelig (johannes.schetelig@ukdd.de). Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article may be accessed from academic researchers after deidentification beginning 18 months and ending 48 months after article publication. Interested researchers must specify the aims and the proposed methodology in a written research proposal to request data access. This proposal will be subject to an independent review. Data access will be granted if the proposal receives a positive evaluation of the independent review committee, and a data transfer agreement has been signed to comply with the European Union directive on data protection.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal