Key Points

In patients who transitioned from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib after ASPEN, BTK inhibitor–associated treatment-emergent AEs were rare.

Overall response at the end of ASPEN was maintained or improved in 44 of 46 efficacy-evaluable patients (96%) in the BGB-3111-LTE1 study.

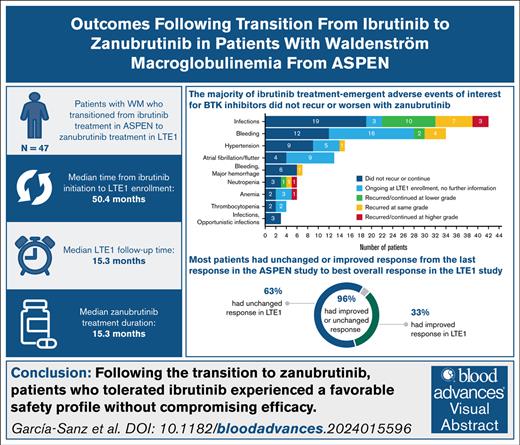

Visual Abstract

Zanubrutinib is a next-generation covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor designed to provide complete and sustained BTK occupancy for efficacy across disease-relevant tissues, with fewer off-target effects than other covalent BTK inhibitors. In the phase 3 ASPEN study (BGB-3111-302), comparable efficacy and a favorable safety profile vs ibrutinib were demonstrated in patients with MYD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response 88)–mutated Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), leading to approval of zanubrutinib for patients with WM. BGB-3111-LTE1 (LTE1) is a long-term extension study to which eligible patients, including patients from comparator treatment arms, could enroll after participation in various parent studies of zanubrutinib to treat B-cell malignancies. Here, safety and efficacy are reported in the 47 patients who transitioned from ibrutinib treatment in ASPEN to zanubrutinib in LTE1. The median time from ibrutinib treatment initiation to LTE1 enrollment was 50.4 months (range, 26-59.3). At median LTE1 study follow-up of 15.3 months (range, 6.0-35.1), 85% of patients in this subgroup remained on zanubrutinib treatment. The median zanubrutinib treatment duration was 15.3 months. Despite advanced and increasing patient age, most ibrutinib treatment-emergent adverse events of interest for BTK inhibitors did not recur or worsen with zanubrutinib. WM disease response was maintained or improved in 44 of 46 efficacy-evaluable patients (96%; n = 2 converted to negative immunofixation). Although limited by sample size and nonrandomized/ad hoc analyses, data suggest that patients who tolerate ibrutinib may switch to zanubrutinib without compromising safety or efficacy. Long-term follow-up is ongoing. These trials were registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03053440 and #NCT04170283.

Introduction

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have become a standard of care in treating patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM).1 Zanubrutinib is a potent, highly selective next-generation covalent BTK inhibitor designed to provide complete and sustained BTK occupancy for efficacy across disease-relevant tissues, with fewer off-target effects compared with other covalent BTK inhibitors.2 Zanubrutinib has demonstrated efficacy across a range of mature B-cell neoplasms in adults in multiple studies3-8 and is now approved in 5 indications: mantle cell lymphoma, WM, marginal zone lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma in 70 regions.9

The phase 3 ASPEN study (BGB-3111-302; www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03053440) directly compared outcomes of zanubrutinib and ibrutinib treatment in patients with WM with the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 L265P mutation (MYD88L265P [myeloid differentiation primary response 88]). Efficacy was comparable for zanubrutinib- and ibrutinib-treated patients.8 Zanubrutinib had a favorable safety profile, with diarrhea, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation occurring less frequently in patients receiving zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib.8 The results of the ASPEN study led to the approval of zanubrutinib for patients with WM.10 At final analysis, improved long-term safety and tolerability of zanubrutinib compared with ibrutinib was confirmed; numerically higher very good partial response (PR; VGPR) plus complete response (CR) rates with earlier and more durable responses were observed in zanubrutinib-treated patients regardless of prior treatment status or CXCR4 and MYD88 mutational status, with no statistically significant differences.11 The BGB-3111-215 study evaluated zanubrutinib treatment in patients with B-cell malignancies previously treated with, and intolerant of, ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or both; 70% of ibrutinib treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and 83% of acalabrutinib TEAEs did not recur during treatment with zanubrutinib, and no events recurred at higher severity, supporting the use of zanubrutinib for patients who are intolerant to ibrutinib or acalabrutinib.12 In the ALPINE study in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma, fatal cardiac AEs were observed in 6 patients in the ibrutinib arm, whereas no deaths due to cardiac AEs were observed in the zanubrutinib arm.3,13 This prompted consideration for transitioning to zanubrutinib, even in patients who tolerate ibrutinib with adequate WM disease control.

Although the advantages of zanubrutinib over other BTK inhibitors have been demonstrated, there are limited data supporting the transition to zanubrutinib treatment. The BGB-3111-LTE1 study (LTE1; www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04170283) is a long-term extension study into which eligible patients, including patients from comparator treatment arms, can enroll after participation in designated studies of zanubrutinib for treatment of B-cell malignancies. Patients from 15 parent studies, in addition to ASPEN, have enrolled in LTE1 from January 2020 to date. Here, we report safety and efficacy outcomes at least 1 year after the transition to zanubrutinib in the LTE1 study, following treatment with ibrutinib in the ASPEN study.

Methods

Study design

The study design, methods, and primary analysis results of the ASPEN study have been described previously,8,14 and the results of the long-term follow-up analysis were published in November 2023.11 Cohort 1 included patients with MYD88L265P randomly assigned 1:1 to receive zanubrutinib, 160 mg twice daily (arm A), or ibrutinib, 420 mg once daily (arm B). Upon enrollment to the LTE1 study, zanubrutinib-naive patients began treatment with zanubrutinib at 160 mg twice daily, including those who required ibrutinib dose modification. In a protocol amendment dated 7 November 2022, a 1-time choice of either 160 mg twice-daily or 320 mg once-daily regimens was introduced, according to approved label indications, to improve flexibility and convenience for patients.

Patients

All patients who enrolled in the LTE1 study after receiving ibrutinib in the ASPEN study (arm B) were included in this ad hoc analysis. Patients were eligible to participate in LTE1 if they had no history of progressive disease (PD) on BTK inhibitor therapy and met the following criteria for adequate organ function: platelets ≥50 000/μL, absolute neutrophil count ≥750/μL, aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase ≤3× upper limit of normal, total bilirubin ≤3× upper limit of normal (not required for cases with documented Gilbert syndrome), increased QT prolongation ≤480 milliseconds, no known New York Heart Association class III or IV congestive heart failure, and creatinine clearance ≥30 mL/min.

Assessments and outcomes

Study visits in LTE1 occurred monthly for the first 3 cycles, then every 3 months. AEs were graded for severity according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.15 Response assessments were required at least every 6 months and continued as performed in the ASPEN study, based on the modified sixth International Workshop on WM criteria16 and using the extent of disease at ASPEN study entry (pre-BTK inhibitor treatment) as the baseline for comparison; investigators also could assess “no evidence of progressive disease” using the data available. Bone marrow biopsy was used to assess bone marrow involvement by WM at screening for the ASPEN study or at baseline, before zanubrutinib treatment, in the LTE1 study, and at suspected CR. For patients with immunoglobulin M (IgM) rebound or PD after ibrutinib interruption or discontinuation before ASPEN end of treatment, the previous response assessment and associated IgM level were used for comparison with the best overall response (BOR) in LTE1. A safety follow-up visit occurred ∼30 days following the end of treatment, after which follow-up information regarding survival and subsequent antineoplastic therapies was obtained every 6 months.

Safety and efficacy outcomes were evaluated and summarized, including the recurrence of ibrutinib TEAEs. Zanubrutinib TEAEs and recurrent or worsening ongoing ibrutinib TEAEs during the LTE1 study were recorded as AEs per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0 in the study database.15 The electronic data capture system was not designed to collect improvements or resolution of medical history diagnoses during study participation. In LTE1, diagnoses and events preceding zanubrutinib treatment, including parent study TEAEs that were ongoing at the time of LTE1 enrollment, were entered as medical history. As such, for ibrutinib-emergent AEs that were ongoing at the time of LTE1 enrollment, there was no reliable mechanism for capturing improvement or resolution during LTE1. Ibrutinib TEAEs that were ongoing at LTE1 enrollment, without worsening during LTE1 and for which no additional information was provided, are shown as “ongoing at LTE1 enrollment, no further information.”

Trial oversight and conduct

The BGB-3111-LTE1 study was approved by the independent institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site and was conducted following applicable regulatory requirements, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization. All patients provided written informed consent.

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

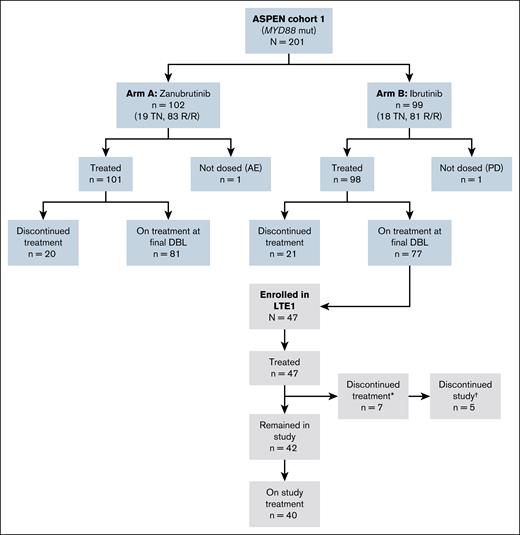

Between 26 June 2020 and 23 June 2022, 47 ibrutinib-treated patients from the ASPEN study enrolled into the LTE1 study (Figure 1). Demographics and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 73 years (range, 44-89). The median number of previous lines of WM therapy was 1 (range, 1-6), and 37 patients (79%) had a history of relapsed/refractory disease on enrollment to the ASPEN study. TEAEs led to ibrutinib treatment interruption or dose reduction in 30 (63.8%) and 11 (23.4%) patients during ASPEN, respectively. TEAEs led to discontinuation of ibrutinib treatment in the ASPEN study in 3 patients who subsequently enrolled in the LTE1 study to receive zanubrutinib. The TEAEs that led to ibrutinib treatment discontinuation included bladder transitional cell carcinoma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and hematuria. The median time from ibrutinib treatment initiation to LTE1 enrollment was 50.4 months (range, 26-59.3). The median time from ASPEN study discontinuation to zanubrutinib initiation in the LTE1 study was 1 day (range, −1 to 7), and the median time from ibrutinib treatment discontinuation to zanubrutinib initiation was 1 day (range, 0-4 months); the time between ASPEN study treatment and LTE1 study treatment was ≤7 days in 43 patients (91%). In the 4 patients with treatment gaps >7 days, ibrutinib was interrupted or withdrawn before ASPEN end of study due to herpes zoster reactivation (22 days), bladder transitional cell carcinoma (57 days), hematuria (95 days), and chronic myeloid leukemia (120 days); 3 of the 4 patients had IgM rebound or PD following ibrutinib treatment interruption before enrollment in LTE1.

CONSORT diagram of the ASPEN and LTE1 studies. ∗Reasons for treatment discontinuation (n = 5 left the study, n = 2 remained in the study): other (n = 3); AEs (n = 2); PD (n = 1); and withdrawal (n = 1). †Reasons for study discontinuation (n = 5): death (n = 3); lost to follow-up (n = 1); and withdrawal (n = 1). DBL, database lock; mut, mutated; R/R, relapsed/refractory; TN, treatment naive.

CONSORT diagram of the ASPEN and LTE1 studies. ∗Reasons for treatment discontinuation (n = 5 left the study, n = 2 remained in the study): other (n = 3); AEs (n = 2); PD (n = 1); and withdrawal (n = 1). †Reasons for study discontinuation (n = 5): death (n = 3); lost to follow-up (n = 1); and withdrawal (n = 1). DBL, database lock; mut, mutated; R/R, relapsed/refractory; TN, treatment naive.

Patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristic . | Patients from ASPEN study who transitioned to zanubrutinib (N = 47) . | |

|---|---|---|

| At parent study enrollment: BGB-3111-302 (ASPEN) . | At LTE enrollment: BGB-3111-LTE1 (LTE1) . | |

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (38-84) | 73 (44-89) |

| <65, n (%) | 16 (34) | 8 (17) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 22 (46.8) | 21 (44.7) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 9 (19.1) | 18 (38.3) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 34 (72.3) | 34 (72.3) |

| Pre-BTK inhibitor treatment status, n (%) | ||

| Treatment naive | 10 (21.3) | |

| Relapsed/refractory | 37 (78.7) | |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (range) | 1 (1-6) | |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 25 (53) | 27 (57.4) |

| 1 | 21 (45) | 17 (36.2) |

| 2 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (4.3) |

| CXCR4 mutation status, n (%) | ||

| WHIM FS | 5 (10.6) | |

| WHIM NS | 2 (4.3) | |

| WT | 38 (80.9) | |

| Unknown | 2 (4.3) | |

| TP53 mutation, n (%) | 8 (17.0) | |

| Characteristic . | Patients from ASPEN study who transitioned to zanubrutinib (N = 47) . | |

|---|---|---|

| At parent study enrollment: BGB-3111-302 (ASPEN) . | At LTE enrollment: BGB-3111-LTE1 (LTE1) . | |

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (38-84) | 73 (44-89) |

| <65, n (%) | 16 (34) | 8 (17) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 22 (46.8) | 21 (44.7) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 9 (19.1) | 18 (38.3) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 34 (72.3) | 34 (72.3) |

| Pre-BTK inhibitor treatment status, n (%) | ||

| Treatment naive | 10 (21.3) | |

| Relapsed/refractory | 37 (78.7) | |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (range) | 1 (1-6) | |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 25 (53) | 27 (57.4) |

| 1 | 21 (45) | 17 (36.2) |

| 2 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (4.3) |

| CXCR4 mutation status, n (%) | ||

| WHIM FS | 5 (10.6) | |

| WHIM NS | 2 (4.3) | |

| WT | 38 (80.9) | |

| Unknown | 2 (4.3) | |

| TP53 mutation, n (%) | 8 (17.0) | |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FS, frameshift mutation; NS, nonsense mutation; WHIM, warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, myelokathexis; WT, wild type.

With a median LTE1 study follow-up of 15.3 months (range, 6.0-35.1) at the data cutoff on 23 June 2023, 40 patients (85%) remained on study treatment with zanubrutinib. The median zanubrutinib treatment duration was 15.3 months (range, 5.1-22.1), and the median BTK inhibitor (ibrutinib + zanubrutinib) treatment duration was 65.5 months (range, 48.1-76.7).

Safety

TEAEs occurring during the ASPEN and LTE1 studies in patients who transitioned to zanubrutinib in LTE1 are summarized in Table 2. TEAEs led to zanubrutinib treatment interruption in 11 patients (23.4%) in LTE1, 8 of whom had prior ibrutinib dose interruption or reduction in ASPEN, and no TEAEs led to zanubrutinib dose reduction in LTE1. Of the 30 patients who had a dose interruption or dose reduction with ibrutinib treatment in ASPEN, 22 (73.3%) switched to zanubrutinib without subsequent dose reduction. Two patients with prior ibrutinib dose interruptions, due to atrial flutter and herpes zoster reactivation, respectively, had interruption of zanubrutinib for COVID-19 infection only; another with history of ibrutinib interruption due to hematuria had zanubrutinib interruptions for urinary tract infection and for COVID-19. Zanubrutinib was interrupted in 2 patients for skin cancer only, and for skin cancer and skin laceration (both recurrent from ASPEN) in another. Finally, zanubrutinib was interrupted due to new TEAEs of anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and prostate cancer in the patient whose ibrutinib treatment was discontinued due to chronic myeloid leukemia before LTE1 enrollment.

Summary of TEAEs in the ASPEN and LTE1 studies

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE, n (%) . | Patients from ASPEN study who transitioned to zanubrutinib (N = 47) . | |

|---|---|---|

| ASPEN: Ibrutinib . | LTE1: Zanubrutinib . | |

| TEAE | 47 (100) | 38 (80.9) |

| Treatment related | 42 (89.4) | 17 (36.2) |

| Serious | 22 (46.8) | 6 (12.8) |

| Treatment related | 15 (31.9) | 0 |

| Leading to treatment discontinuation | 3 (6.4) | 2 (4.3) |

| Leading to dose reduction | 11 (23.4) | 0 |

| Leading to dose interruption | 30 (63.8) | 11 (23.4) |

| Fatal TEAE | NA | 2 (4.3) |

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE, n (%) . | Patients from ASPEN study who transitioned to zanubrutinib (N = 47) . | |

|---|---|---|

| ASPEN: Ibrutinib . | LTE1: Zanubrutinib . | |

| TEAE | 47 (100) | 38 (80.9) |

| Treatment related | 42 (89.4) | 17 (36.2) |

| Serious | 22 (46.8) | 6 (12.8) |

| Treatment related | 15 (31.9) | 0 |

| Leading to treatment discontinuation | 3 (6.4) | 2 (4.3) |

| Leading to dose reduction | 11 (23.4) | 0 |

| Leading to dose interruption | 30 (63.8) | 11 (23.4) |

| Fatal TEAE | NA | 2 (4.3) |

NA, not applicable.

Two patients discontinued study treatment with zanubrutinib due to TEAEs, which included COVID-19 in 1 patient and hematuria in the patient previously mentioned. This patient, who had previous history of subarachnoid hemorrhage, prostate cancer, urethral stenosis, and urostomy before ASPEN participation, developed rectal bleeding, stoma site bleeding, and hematuria during ibrutinib treatment in ASPEN; hematuria was grade 1 in severity initially, recurred 1 year later at grade 3, and after 5 months at grade 2 resulted in discontinuation of ibrutinib; hematuria was ongoing at enrollment in LTE1 3 months after ibrutinib was discontinued, increased in severity after initiation of zanubrutinib to grade 3 for 3 weeks, then persisted at grade 1 to 2 until zanubrutinib discontinuation 6 months from zanubrutinib initiation; the patient died 1 year later due to bronchopneumonia, after having received a noncovalent BTK inhibitor in the interim.

TEAEs that occurred during the LTE1 study are further described in Table 3. Grade ≥3 and serious TEAEs occurred in 11 (23.4%) and 6 patients (12.8%), respectively. Infections were the only grade ≥3 TEAEs occurring in >2 patients and were all due to COVID-19 (n = 3 [6.4%]). No serious TEAEs occurred in more than 2 patients. Two deaths occurred in the LTE1 study, due to COVID-19 pneumonitis after treatment with dexamethasone, baricitinib, piperacillin/tazobactam, and bisoprolol in 1 patient and due to multifactorial respiratory failure in 1 patient. The incidences of TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors following transition to zanubrutinib are presented in Table 3.

Grade 3 or more TEAEs, serious TEAEs, and TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors in the LTE1 study

| . | Patients in LTE1 (N = 47) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade ≥3 TEAEs in ≥2 patients (5%), by preferred term, n (%) | ||

| Anemia | 2 (4.3) | |

| COVID-19/COVID-19 pneumonia grouped | 3 (6.4) | |

| Neutropenia/neutrophil count decreased grouped | 2 (4.3) | |

| Serious TEAEs in ≥2 patients (5%), by preferred term: pericarditis, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | |

| TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors, n (%) | Any grade | Grade ≥3 |

| Infections | 22 (46.8) | 3 (6.4) |

| Hypertension | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| Hemorrhage | 6 (12.8) | 1 (2.1) |

| Neutropenia, grouped term | 5 (10.6) | 2 (4.3) |

| Anemia, grouped term | 4 (8.5) | 2 (4.3) |

| Second primary malignancies: skin cancers | 4 (8.5) | 0 |

| Second primary malignancies: nonskin cancers | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia, grouped term | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| . | Patients in LTE1 (N = 47) . | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade ≥3 TEAEs in ≥2 patients (5%), by preferred term, n (%) | ||

| Anemia | 2 (4.3) | |

| COVID-19/COVID-19 pneumonia grouped | 3 (6.4) | |

| Neutropenia/neutrophil count decreased grouped | 2 (4.3) | |

| Serious TEAEs in ≥2 patients (5%), by preferred term: pericarditis, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | |

| TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors, n (%) | Any grade | Grade ≥3 |

| Infections | 22 (46.8) | 3 (6.4) |

| Hypertension | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| Hemorrhage | 6 (12.8) | 1 (2.1) |

| Neutropenia, grouped term | 5 (10.6) | 2 (4.3) |

| Anemia, grouped term | 4 (8.5) | 2 (4.3) |

| Second primary malignancies: skin cancers | 4 (8.5) | 0 |

| Second primary malignancies: nonskin cancers | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia, grouped term | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

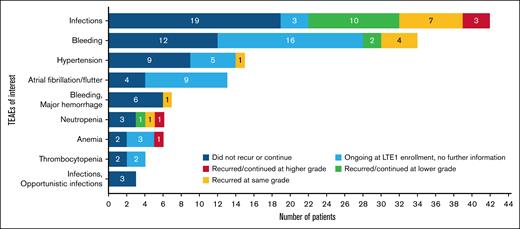

Ibrutinib TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitor treatment and their outcomes following transition to treatment with zanubrutinib are shown in Figure 2. Ibrutinib TEAEs that were ongoing at time of enrollment in the LTE1 study, but for which there were no increases in severity, are reported as “ongoing at LTE1 enrollment, no further information,” as there was no mechanism in the study database to collect subsequent improvement in severity or resolution, as discussed in the “Methods.” Most ibrutinib TEAEs did not recur or worsen with zanubrutinib. Worsening of ibrutinib TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitor treatment after the transition to zanubrutinib included infections (n = 3), all of which were due to COVID-19, anemia (n = 1), and neutropenia (n = 1). No ongoing hypertension worsened in severity, and no new or recurrent episodes of hypertension occurred after patients switched from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib.

Recurrence or continuation of ibrutinib TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors after transition to zanubrutinib.

Recurrence or continuation of ibrutinib TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors after transition to zanubrutinib.

Seven patients experienced 8 cardiovascular TEAEs in the LTE1 study, 6 of whom had experienced at least 1 cardiovascular TEAE during ibrutinib treatment in the ASPEN study. The patient without prior cardiovascular ibrutinib TEAEs developed grade 2 tachycardia in the LTE1 study. No new episodes of hypertension occurred after patients switched from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib, and no ongoing or recurrent hypertension worsened. No resolved ibrutinib treatment–emergent atrial fibrillation/flutter recurred, and no ongoing atrial fibrillation/flutter worsened following the transition to zanubrutinib. One new case of atrial fibrillation occurred in the LTE1 study on day 13 in a patient with history of ventricular arrythmia and hypertension and in whom grade 2 pericarditis was diagnosed 2 days prior (LTE1 day 11); pericarditis resolved, was assessed to be unrelated to zanubrutinib and attributed to preceding grade 3, serious viral infection per investigator, and study treatment with zanubrutinib was resumed. Two other patients with history of prior cardiovascular AEs on ibrutinib in the ASPEN study developed pericarditis during the LTE1 study, at 4 and 9 months of zanubrutinib treatment, respectively. Pericarditis resolved, study treatment with zanubrutinib was resumed, and the investigator assessed pericarditis as unrelated to zanubrutinib (1 possibly due to a preceding viral infection, and cardiovascular medical history was considered a contributing factor in both). No fatal cardiovascular TEAEs occurred in the LTE1 study.

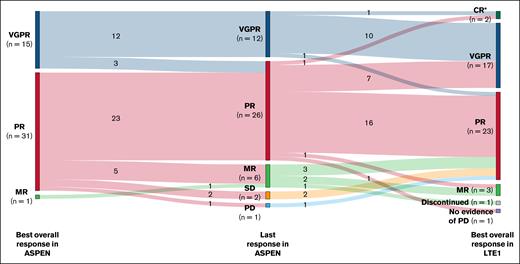

Efficacy

Rates of BOR during the ASPEN study, response assessment at ASPEN end of study, and BOR during the LTE1 study are shown in Figure 3. One patient withdrew consent before first response assessment. Categorical BOR in LTE1 was unchanged (n = 29 [63%]) or improved (n = 15 [33%]) from the last response in the ASPEN study in 44 of 46 efficacy-evaluable patients (96%). Two patients, 1 with PR and 1 with VGPR at the end of the ASPEN study, met serum IgM criteria for CR and had normalization of serum IgM with negative immunofixation on zanubrutinib in the LTE1 study. Bone marrow examination was declined in both cases.

Overall response assessments in patients receiving ibrutinib in the ASPEN study and zanubrutinib in the LTE1 study. ∗CR (n = 2) was assessed by the investigators based on serum IgM and negative immunofixation; they were not confirmed by bone marrow biopsy. MR, minor response.

Overall response assessments in patients receiving ibrutinib in the ASPEN study and zanubrutinib in the LTE1 study. ∗CR (n = 2) was assessed by the investigators based on serum IgM and negative immunofixation; they were not confirmed by bone marrow biopsy. MR, minor response.

One patient’s (CXCR4WHIM frameshift/TP53WT) level of disease control decreased from PR to minor response after the last response assessment in ASPEN and returned to PR on zanubrutinib after the data cutoff for this analysis. Finally, the patient (CXCR4WT/TP53WT) previously mentioned, who had a 57-day treatment interruption due to bladder transitional cell carcinoma, experienced IgM rebound with improvement to PR at end of ASPEN and return to VGPR on zanubrutinib after the data cutoff for this analysis.

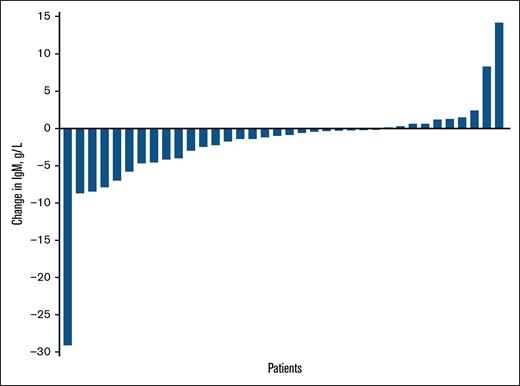

Change in IgM concentration from last response assessment in the ASPEN study to BOR in the LTE1 study is plotted for each patient in Figure 4. The median change in IgM concentration from the last response assessment in the ASPEN study to BOR in the LTE1 study was −60 mg/dL (range, −2910 to +1420); for the 4 patients with gaps of >7 days between end of study treatment in ASPEN and zanubrutinib initiation in LTE1, the change in IgM concentration from screening to BOR in LTE1 was −118 to 930 mg/dL.

Change in IgM from last response assessment in the ASPEN study to BOR in the LTE1 study.

Change in IgM from last response assessment in the ASPEN study to BOR in the LTE1 study.

Discussion

With a median zanubrutinib treatment duration of 15 months, patients with WM safely transitioned from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib in the LTE1 study. Most TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors observed with ibrutinib did not recur or worsen after transition to zanubrutinib; the emergence of new TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors was rare with zanubrutinib treatment, with infrequent recurrence or worsening of hypertension and atrial fibrillation being most remarkable.

WM disease response was maintained or improved in most patients. Furthermore, both patients whose disease response was not maintained or improved between the end of ASPEN and BOR in LTE1 by the data cutoff for this analysis later returned to previous level of disease control (PR and VGPR). Overall, these results indicate that transitioning from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib does not lead to worsening of disease control and, in some cases, may lead to improvement in efficacy.

Study limitations include small sample size, lack of a formal control group, nonrandomized/ad hoc analysis, a relatively short 15.3-month follow-up after the transition to zanubrutinib, and the inherent biases associated with the extension study, including selection and attrition biases. Patients with a history of PD on ibrutinib and with inadequate organ function were ineligible. This limits comparisons to outcomes in patients continuing zanubrutinib and is 1 factor in the rationale for descriptive intrapatient analysis of TEAEs before and after transition to zanubrutinib.

This subgroup of patients receiving zanubrutinib in the LTE study had received an in-class drug for 2 to 4 years before enrollment. Patients, investigators, and research staff may be less likely to acknowledge or report AEs in a long-term extension study of a now widely approved medication compared with a phase 3 randomized, registrational trial before approval.

The LTE1 study includes patients from 15 parent studies of zanubrutinib; it was designed to follow long-term safety and efficacy of zanubrutinib and to facilitate long-term access to zanubrutinib for patients who participated in early and registrational studies. Most patients enrolled either continued zanubrutinib treatment from the parent study or entered survival follow-up after zanubrutinib discontinuation in the parent study. The decision to allow patients who were treated on comparator arms to enroll if they chose to transition to zanubrutinib was made to facilitate equitable access to ongoing treatment after their parent study participation. AEs reported after treatment with zanubrutinib began were considered zanubrutinib emergent, and ongoing ibrutinib-emergent events were recorded as medical history. Details regarding ibrutinib TEAEs would thus be captured in the LTE1 database only if the severity of an ongoing ibrutinib TEAE increased or if a previously resolved ibrutinib TEAE recurred. The benefits of transition from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib may have been underestimated by the limitations of the clinical database design.

Of note, any TEAEs within the AE of special interest categories are counted as recurrence/worsening for each patient as applicable; for instance, a second or subsequent infection in LTE1 unrelated to the first in ASPEN is counted as a recurrence of an infection AE of special interest. It is also important to consider that increasing comorbidities would be expected, independent of treatment, related to advanced age during LTE1 study participation (median age at LTE1 enrollment was 73 years).

Response assessments, which followed the same frequency and were based on the same response criteria as in the parent study, were required at least every 6 months per LTE1 study protocol, but methods employed were at the investigators’ discretion. As such, scans and bone marrow evaluation may not have been performed as frequently as required in a registrational trial, as was seen with 2 patients with negative immunofixation but for whom bone marrow examinations were not performed.

An ad hoc analysis of outcomes of extended follow-up of patients who received zanubrutinib in the ASPEN study (cohort 1, arm A and cohort 2) demonstrated that the prevalence of most TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitors decreased with ongoing treatment. Disease responses were durable and, in some cases, deepened over time.17 Outcomes in zanubrutinib-treated subgroups cannot be compared directly to the present analysis, as (1) patients in this cohort were treated with both ibrutinib and zanubrutinib with overlapping treatment-emergent periods and (2) patients were not randomly assigned to treatment at parent study completion; they chose whether to enroll in LTE1 to continue or transition to zanubrutinib, vs continuing their parent study treatment off-trial, pursuing another therapeutic option, or discontinuing treatment.

The phase 3, registrational ASPEN and ALPINE studies in patients with WM and chronic lymphocytic leukemia demonstrated the advantages of BTK inhibitor treatment with zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib by direct comparisons.3,8,11 In the BGB-3111-215 study of zanubrutinib for patients with B-cell malignancies previously treated with and intolerant of ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or both, most intolerance events did not recur.12 Although advantages of zanubrutinib have been demonstrated previously, this analysis sought to address, with data available through the zanubrutinib long-term extension study, whether the transition to zanubrutinib in responding patients who tolerate ibrutinib impacts WM disease control. Despite the acknowledged limitations of the long-term extension study design, including lack of a control group composed of patients continuing to receive ibrutinib long term after treatment in ASPEN, the results of this analysis provide useful information to health care providers.

In conclusion, in patients with WM from the ASPEN study who transitioned from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib, WM disease response was maintained or improved. Worsening or newly occurring TEAEs of interest for BTK inhibitor treatment were rare. Outcomes at ≥1 year after transition to zanubrutinib suggest that patients with WM response and tolerating ibrutinib experienced a favorable safety profile without compromising efficacy upon transition to zanubrutinib. Follow-up is ongoing to further describe the long-term outcomes of transition from ibrutinib to zanubrutinib.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families, investigators, coinvestigators, and the study teams at each of the participating centers. This study was sponsored by BeOne Medicines Ltd. Editorial assistance was provided by Nucleus Global, an Inizio company, and supported by BeOne Medicines Ltd. This study was funded by BeOne Medicines Ltd.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed to the conception/design, data acquisition, data analysis, and data interpretation of the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.G.-S. reports consultancy roles for Janssen and BeOne Medicines Ltd; research funding from Gilead and Takeda; honoraria from Janssen, Takeda, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Incyte, Astellas, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); patents and royalties from IVS Technologies (institutional agreement); and participation in the speakers’ bureau for Janssen and BeOne Medicines Ltd. R.G.O. declares consultancy roles for BeOne Medicines Ltd and Janssen; honoraria from BeOne Medicines Ltd, Janssen, and AstraZeneca; and meetings/travel expenses from BeOne Medicines Ltd. W.J. reports consultancy roles for Janssen, AstraZeneca, MEI Pharma, Lilly, Takeda, Roche, AbbVie, and BeOne Medicines Ltd; and research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Celgene, Janssen, Roche, Takeda, TG Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, MEI Pharma, and Lilly. M.A.D. reports serving on advisory boards for Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), BeOne Medicines Ltd, Janssen, GSK, Menarini, Takeda, Regeneron, and Sanofi; and receiving honoraria from Amgen, AbbVie, BMS, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Janssen, GSK, Menarini, Takeda, Regeneron, and Sanofi. H.M. reports honoraria from BeOne Medicines Ltd and Janssen. G.C. reports research funding from BeOne Medicines Ltd, AstraZeneca, and Glycomimetics. S.S.O. reports consulting fees from AbbVie, Antengene, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, BMS, CSL Behring, Gilead, Merck, Novartis, Janssen, Roche, and Takeda; research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, Roche, and Takeda; honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Takeda; and membership on an entity’s board of directors or advisory committees for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeOne Medicines Ltd, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Takeda, outside the submitted work. J.J.C. reports research funding from AbbVie, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Cellectar, Loxo, and Pharmacyclics; and consultancy roles for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Avilar, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Cellectar, Janssen, Loxo, Mustang Bio, Nurix, and Pharmacyclics. M.J.K. reports consultancy roles for Kite/Gilead, Novartis, BMS, Miltenyi Biotec, Adicet Bio, and Galapagos; research funding from Kite/Gilead; honoraria from BeOne Medicines Ltd, Kite/Gilead, Roche, and BMS; and travel support from Roche and AbbVie. B.E.W. reports holding stock in Genmab. R.P. and T.T. report employment with BeOne Medicines Ltd. H.A. reports being an employee and equity holder in publicly traded companies BeOne Medicines Ltd and Nkarta Therapeutics; and patents and royalties from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. A.C.C. reports employment by BeOne Medicines Ltd; equity holder for BeOne Medicines Ltd; and travel, accommodations, and expenses from BeOne Medicines Ltd. C.S.T. declares research funding from Janssen, AbbVie, and BeOne Medicines Ltd; and honoraria from Janssen, AbbVie, BeOne Medicines Ltd, Loxo, and AstraZeneca. S.G. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ramón García-Sanz, Hematology Department, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, C del Dr Esquerdo, 46, Retiro, 28007 Madrid, Spain; email: rgarcias@usal.es.

References

Author notes

BeOne Medicines voluntarily shares anonymous data on completed studies responsibly and provides qualified scientific and medical researchers access to anonymous data and supporting clinical trial documentation for clinical trials in dossiers for medicines and indications after submission and approval in the United States, China, and Europe. Clinical trials supporting subsequent local approvals, new indications, or combination products are eligible for sharing once corresponding regulatory approvals are achieved. BeOne Medicines shares data only when permitted by applicable data privacy and security laws and regulations. In addition, data can only be shared when it is feasible to do so without compromising the privacy of study participants. Qualified researchers may submit data requests/research proposals for BeOne Medicines review and consideration through BeOne Medicines’ clinical trial webpage at https://beonemedicines.com/science/clinical-trials.