Key Points

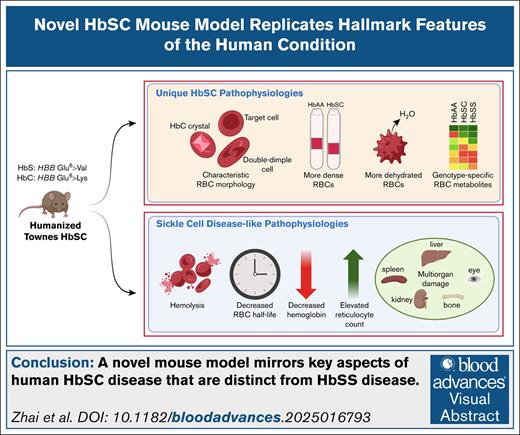

Mouse model for HbSC disease replicates key features of human HbSC disease.

Humanized HbSC mouse model serves as a tool for studying the disease's unique pathophysiology and advancing the development of treatments.

Visual Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a common, life-threatening group of disorders caused by missense mutations in the β-globin gene (HBB). Mouse models have helped to elucidate the most common form of SCD (hemoglobin SS [HbSS]; homozygous p.Glu6Val) and develop new therapies. In contrast, a lack of animal models has restricted research on the second most common form of SCD (hemoglobin SC [HbSC]; p.Glu6Val/p.Glu6Lys). We used CRISPR genome engineering to generate HbSC alleles in the Townes mouse strain, which harbors human α- and β-globin genes in place of the mouse counterparts. Compared to Townes HbSS mice, HbSC mice exhibited signature pathologies that distinguish HbSC disease in humans.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) encompasses a group of recessive disorders caused by missense mutations in the HBB gene, which encodes the β-globin subunit of adult hemoglobin (HbA; α2β2).1-4 The most common SCD genotype is homozygous HBB p.Glu6Val (genotype HBBSS), referred to as hemoglobin SS (HbSS) disease or sickle cell anemia. Under low oxygen conditions, mutant HbSS tetramers (α2βS2) form stiff polymers, causing red blood cells (RBCs) to acquire a characteristic sickle shape and triggering a complex pathophysiology that includes hemolysis, vascular occlusion, inflammation, and oxidative stress, often leading to multiorgan damage and early mortality. The second most common SCD genotype is compound heterozygous HBB p.Glu6Val and p.Glu6Lys (genotype HBBSC), referred to as hemoglobin SC (HbSC) disease. Approximately 30% of people with SCD have the HbSC subtype, although the frequency varies according to geographic ancestry and is particularly high in parts of West Africa.5-10

HbSC and HbSS diseases exhibit overlapping and distinct pathological features and clinical manifestations. Unlike hemoglobin S (HbS), HbC does not polymerize with hypoxia. Instead, HbC increases the activity of K:Cl cotransport (KCC) in RBCs, resulting in the loss of intracellular K+ and water.11 Heterozygosity for HbC or HbS have minimal clinical consequences. However, in compound heterozygotes (HbSC disease), RBC dehydration caused by HbC promotes polymerization of HbS.12-14 Compared to HbSS disease, HbSC disease is associated with higher RBC Hb concentration, greater blood viscosity, reduced hemolysis, and less oxidative tissue damage caused by circulating free heme.15,16 Children with HbSC disease generally have a milder clinical course than those with HbSS disease. However, recent studies report that HbSC disease is more severe than was previously recognized, particularly in adults.17,18 A study in Ghana showed that adults (ages 18-45 years) with HbSC disease have higher rates of proliferative retinopathy and systemic hypertension than those with HbSS disease, as well as similar rates of bone avascular necrosis (AVN) and stroke.19 In the SCD Implementation Consortium, individuals with HbSC disease (ages 15-45 years) were found to have higher rates of splenomegaly and retinopathy than those with HbSS disease.17 Bone AVN, pulmonary embolism, and acute chest syndrome are also common in adults with HbSC disease.17 Compared to HbSS disease, HbSC disease remains understudied and less well understood, and until recently, affected individuals were often excluded from clinical trials for experimental therapies.17,19,20

Mouse models for HbSS disease have been used to elucidate the pathophysiology of the disease and to explore potential new therapies.21 The lack of a similar model for HbSC disease represents a major limitation. To facilitate research on the pathophysiology and treatment of HbSC disease, we have generated HbSC mice via CRISPR genome editing of the Townes strain,22 which harbors human α-globin (HBA1), γ-globin (Aγ, HBG1), and β-globin (HBB) genes in place of orthologous mouse globin genes.22,23 Comparison of HbSS, HbSC, and HbAA (wild type) strains in similar genetic backgrounds revealed that Townes HbSC mice recapitulate hallmark features of human HbSC disease, including dense, dehydrated RBCs with characteristic morphology, moderate hemolysis, and a tendency toward accelerated retinopathy. This new mouse strain provides a valuable resource for HbSC disease research.

Materials and methods

See the supplemental Methods for additional details.

Mice

Townes mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (strain number 013071) and bred to establish a colony. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee [IACUC] protocol number 579).

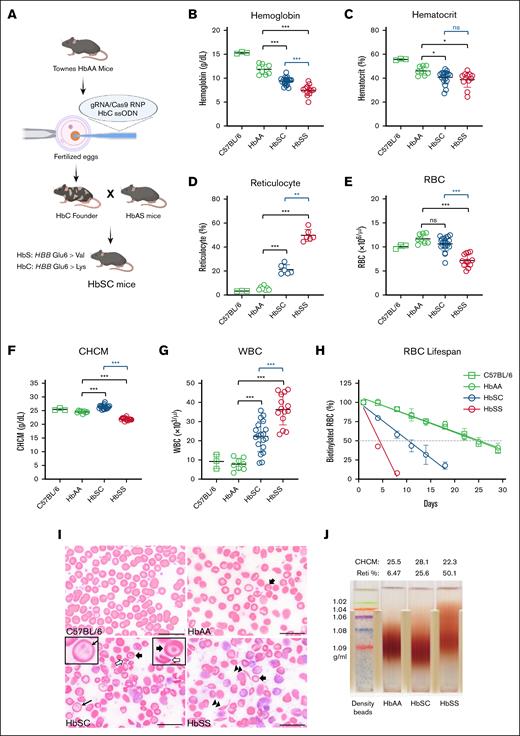

Generation of HbSC mice using CRISPR technology was conducted as described previously24 and shown in Figure 1A. Fertilized eggs from Townes nonsickling HbAA mice were microinjected with ribonucleoprotein consisting of 3× nuclear localization signal (NLS) SpCas9 and chemically modified single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting HBB exon 1, along with an ssODN donor designed to convert wild-type HBB codon 6 (GAG; Glu) into HbC (AAG; Lys). Offspring were screened to identify HBBC founders and interbred with isogenic HbAS Townes mice to create an HbSC Townes line. Age-matched, mixed-sex mice were used for analysis.

HbSC and HbSS mice exhibit distinct hematological properties. (A) Schematic representation of the generation of humanized HbSC mice. (B-G) Hematological indices in 4-month-old HbAA (n = 8; sex combined), HbSC (n = 19; sex combined), and HbSS mice (n = 12; sex combined) for Hb levels (B), hematocrit (C), reticulocyte counts (D), RBC counts (E), CHCM (F), and white blood cell (WBC) counts (G). (H) Shortened RBC life span in HbSC and HbSS mice. (I) Representative peripheral blood smears from C57BL/6, HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice. Thick arrows indicate target cells; hollow arrows, HbC crystal; thin arrow, double dimple cell; and double arrowhead, sickle cell. (J) Percoll density gradient analysis showing dense RBCs in HbSC mice. Hypodense RBCs apparent in HbSS mice probably represent reticulocytes. Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in green; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Scale bars, 20 μm. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. CHCM, cellular Hb concentration mean; ns, no significant difference; RBC, red blood cell; Reti, reticulocyte.

HbSC and HbSS mice exhibit distinct hematological properties. (A) Schematic representation of the generation of humanized HbSC mice. (B-G) Hematological indices in 4-month-old HbAA (n = 8; sex combined), HbSC (n = 19; sex combined), and HbSS mice (n = 12; sex combined) for Hb levels (B), hematocrit (C), reticulocyte counts (D), RBC counts (E), CHCM (F), and white blood cell (WBC) counts (G). (H) Shortened RBC life span in HbSC and HbSS mice. (I) Representative peripheral blood smears from C57BL/6, HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice. Thick arrows indicate target cells; hollow arrows, HbC crystal; thin arrow, double dimple cell; and double arrowhead, sickle cell. (J) Percoll density gradient analysis showing dense RBCs in HbSC mice. Hypodense RBCs apparent in HbSS mice probably represent reticulocytes. Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in green; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Scale bars, 20 μm. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. CHCM, cellular Hb concentration mean; ns, no significant difference; RBC, red blood cell; Reti, reticulocyte.

Blood collection

Peripheral blood samples were collected via retro-orbital bleed from anesthetized mice. Whole blood was collected via intracardiac puncture under anesthesia as a terminal procedure.

Complete blood counts

Blood samples were analyzed using the ADVIA 2120i Hematology System (Siemens Healthineers) for hematological indices.

RBC density gradient

The density of RBCs was measured using a Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Percoll gradient was established by centrifugation in a JA-21 rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 40 000g for 30 minutes at 37°C. Tubes were aligned and photographed (Nikon D7500).

Flow cytometry

Determination of RBC half-life

RBCs were labeled with biotin and flow cytometry was used to follow the fraction of labeled cells over time as previously described.27 Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo (FlowJo LLC).

HPLC

Hb proteins in RBC lysates were quantified with reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using the Prominence HPLC System (Shimadzu Corporation). Proteins were quantified by light absorbance at 220 nm. The relative amounts of specific Hb were estimated by determining the area under each absorbance peak.

Osmotic and oxygen gradient ektacytometry

Deformability of RBCs, expressed as elongation index (EI), was analyzed using the Laser-Optical Rotational Red Cell Analyzer (LoRRca MaxSis Ektacytometer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Osmoscan calculates EImin, EImax, Omin (osmolality at EImin), Omax (osmolality at EImax), and Ohyper (osmolality corresponding to 50% of EImax). Oxygenscan calculates the relative oxygen pressure at which RBCs begin to sickle.

General pathology studies

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were acquired with an Olympus SC180 camera on an Olympus BX46 microscope. The Prussian blue assay was performed using an Iron Stain Kit (Roche Diagnostics) in conjunction with a BenchMark Special Stains automated instrument (Roche Diagnostics).

μCT of bone

Femurs were fixed in 10% (v/v) formalin for 24 hours and imaged using microcomputed tomography (μCT; Inveon, Siemens). Inveon Research Workplace (Siemens) was used to review and analyze images. Trabecular bone volume–to–total volume ratio (BV/TV) was calculated as previously described.28 Cortical wall thickness was calculated as an average of 4 points at the middiaphysis of each femur.

DXA

Mice were assessed for bone mineral density (BMD) by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using Lunar PIXImus2 Densitometer (GE Medical Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions (12759224). BMD was measured by defined region of interest of the whole body, femur, and lumbar vertebrae. Absolute BMD values are expressed in grams per square centimeter.

Retina flat mount immunofluorescence and vessel quantification

For retinal tissue preparation, immunostaining, imaging, and quantitative vascular analysis, mouse eyes were enucleated, fixed in paraformaldehyde, and the retinas were dissected and blocked before incubation with primary and secondary antibodies. The retinas were then mounted and imaged using fluorescence and confocal microscopy. Image analysis involved segmentation of retinal layers and blood vessels using 3-dimensional U-Net models and 3DVascNet. Blood vessel characteristics, such as branch distance and tortuosity, were quantified, and quality control ensured accuracy in segmentation and analysis.

Metabolomics

RBC metabolomics were performed as described previously.29,30 RBCs were resuspended in prechilled 80% methanol. After 3 freeze-thaw cycles, cell lysates were centrifuged at 21 000g for 20 minutes, and the supernatant was lyophilized overnight. Dried metabolites were reconstituted in 100 mobile phase A. Data acquisition was performed by reverse-phase chromatography on an Agilent 1290 Infinity II Series Bio-inert HPLC system interfaced to a high-resolution mass spectrometry 6546 Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). Raw data files were processed using Profinder B.08.00 SP3 (Agilent Technologies). Enriched metabolite sets and pathways were identified with MetaboAnalyst 5.0.31

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were conducted with a 1- or 2-way analysis of variance for multiple group comparisons, with each genotype compared to Townes HbAA mice, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for 2-group comparisons. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10 for Windows (v0.2.3(403). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HbSC and HbSS mice exhibit distinct RBC characteristics

HbSC mice were derived from the Townes HbAA strain by CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair (Figure 1A; “Materials and methods”; supplemental Methods) and compared to HbAA and HbSS mice. Analysis of RBC lysates from HbSC mice by reverse-phase HPLC revealed 56.5% ± 1.1% HbS (βS) and 43.5% ± 1.1% HbC (βC; supplemental Figure 1A-B), which differs slightly from the 50:50 ratio described for human patients.12,16,32 No fetal Hb was detected in RBCs from HbSC mice.

Four-month-old HbSC and HbSS mice exhibited signs of hemolytic anemia, including low Hb and hematocrit with increased reticulocyte percentages (Figure 1B-D). The average Hb levels in HbSS and HbSC mice were 7.46 ± 1.31 g/dL and 9.38 ± 0.81 g/dL, respectively. HbSC mice exhibited a significantly lower reticulocyte count than HbSS mice. The HbSS mice, but not HbSC mice, exhibited a significantly lower RBC count than HbAA mice (Figure 1E). The cellular Hb concentration mean was elevated in HbSC mice (Figure 1F), indicating RBC dehydration. The white blood cell count was elevated in both SCD strains, although to a greater extent in HbSS mice (Figure 1G). Platelet counts were similar in all genotypes (supplemental Table 1). Biotin labeling studies showed RBC half-lives of 25, 10.5, and 4.3 days in HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice, respectively (Figure 1H). Findings in 12-month-old mice were similar to those in 4-month-old mice, although the Hb and hematocrit levels were generally lower in older animals (supplemental Table 2). Additional markers of hemolysis including serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, and aspartate aminotransferase were significantly higher in HbSS mice (supplemental Table 3). Together, these studies indicate that HbSC mice have less severe anemia and reduced hemolysis compared to HbSS mice.

Peripheral blood smears of 4-month-old mice showed distinct morphologies for each genotype (Figure 1I). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice had normal RBC morphology, whereas Townes HbAA RBCs exhibited occasional hypochromic cells, target cells, and spherocytes. HbSS RBCs exhibited sickled cells, polychromasia, anisocytosis, and poikilocytosis. HbSC RBCs exhibited distinct morphology, including fewer sickled cells, more target cells, HbC crystals, and “double dimple” RBCs, similar to patients with HbSC (Figure 1I).

The HbC protein causes RBC dehydration, which is consistent with our observation that cellular Hb concentration mean was highest in HbSC mice. To investigate this further, we used Percoll gradients to analyze RBC density in 4-month-old mice (Figure 1J). As expected, HbSC mice had denser RBCs than HbSS or HbAA mice.

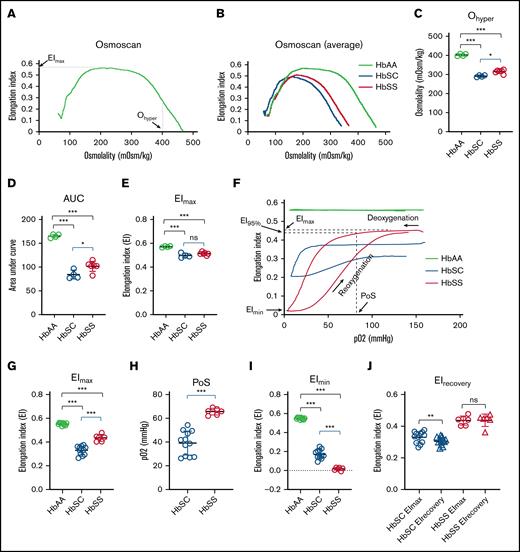

Distinct deformability profiles in RBCs from HbSS and HbSC Townes mice

RBCs from patients with HbSS or HbSC disease exhibit distinct abnormalities in deformability, which contribute to SCD pathophysiology by promoting microvascular occlusion.33 We compared RBCs from HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice using laser-assisted optical rotational cell analyzer, which measures cell deformability during exposure to an applied shear stress.34 RBC deformability, expressed as EI, varies across an osmotic gradient, which affects membrane properties, hydration state, and HbS polymerization (Figure 2A). Compared to RBCs from HbAA mice, HbSS and HbSC RBCs exhibited left-shifted osmotic deformability curves, indicating cellular dehydration (Figure 2B). Specifically, Ohyper, which reflects cellular hydration status, was reduced in RBCs from both SCD strains but to a greater extent in HbSC mice (Figure 2C), recapitulating the more pronounced RBC dehydration observed in RBCs from patients with HbSC disease. Similar abnormalities occurred with the area under the curve, which reflects overall stability of RBCs to shear stress over the range of tolerated osmolarities (Figure 2D). The maximal EI (EImax), which reflects RBC membrane shape and rigidity, was equally reduced in RBCs from HbSS and HbSC mice (Figure 2E). We observed similar trends in RBC osmotic deformability curves of patients with HbSS or HbSC disease (supplemental Figure 2).

HbSC RBCs exhibit distinct deformability profiles in osmotic or oxygen gradient ektacytometry. (A) Representative LoRRca osmoscan profiles for a 4-month-old HbAA mouse showing key indices. (B) Average osmoscan curves for HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice showing a leftward shift with HbSS (red) and HbSC (blue) compared to HbAA (green) mice. (C) Significant reduction of Ohyper in HbSC and HbSS mice compared to HbAA mice. (D) Reduced area under curve (AUC) in HbSC and HbSS mice. (E) Reduced EImax in HbSC and HbSS mice. (F) Representative LoRRca oxygenscan profiles for 4-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice. (G) Significant decrease of EImax in HbSC and HbSS mice. (H) Significant reduction in point of sickling at which the EI decreases to 95% of EImax in HbSC vs HbSS mice. (I) Significant reduction of EImin in HbSC and HbSS mice. (J) Persistent increase in deformability of RBCs from HbSC mice after deoxygenation-reoxygenation (HbAA, n = 10; HbSC, n = 12; HbSS, n = 6). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, no significance.

HbSC RBCs exhibit distinct deformability profiles in osmotic or oxygen gradient ektacytometry. (A) Representative LoRRca osmoscan profiles for a 4-month-old HbAA mouse showing key indices. (B) Average osmoscan curves for HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice showing a leftward shift with HbSS (red) and HbSC (blue) compared to HbAA (green) mice. (C) Significant reduction of Ohyper in HbSC and HbSS mice compared to HbAA mice. (D) Reduced area under curve (AUC) in HbSC and HbSS mice. (E) Reduced EImax in HbSC and HbSS mice. (F) Representative LoRRca oxygenscan profiles for 4-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice. (G) Significant decrease of EImax in HbSC and HbSS mice. (H) Significant reduction in point of sickling at which the EI decreases to 95% of EImax in HbSC vs HbSS mice. (I) Significant reduction of EImin in HbSC and HbSS mice. (J) Persistent increase in deformability of RBCs from HbSC mice after deoxygenation-reoxygenation (HbAA, n = 10; HbSC, n = 12; HbSS, n = 6). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, no significance.

Next, we assessed RBC deformability during exposure to an oxygen gradient.35 The EI of RBCs from HbAA mice did not change with reduction in pO2 (Figure 2F). As expected, RBCs from HbSC and HbSS mice exhibited reductions in EI during deoxygenation, consistent with Hb polymerization causing impaired deformability. At normoxia, RBCs from HbSC mice exhibited a lower EI than RBCs from HbSS mice (EImax; Figure 2F-G). Sickling of HbSS RBCs occurred at a higher pO2 than HbSC RBCs, as reflected by differences in the point of sickling (Figure 2F,H). The deformability after deoxygenation (EImin) was lower for HbSS RBCs than for HbSC RBCs (Figure 2F,I). Upon reoxygenation, the EI (EIrecovery) of HbSS RBCs recovered to near baseline, whereas the EIrecovery of HbSC RBCs was reduced compared to EImax (Figure 2F,J). Thus, brief, extreme deoxygenation caused reduced capacity to recover the deformability of HbSC RBCs but not HbSS RBCs, indicating distinct unsickling processes. Similarly, two different human studies have shown lower point of sickling and reduced EIrecovery in HbSC RBCs vs HbSS RBCs.35,36

Ineffective erythropoiesis in HbSS and HbSC mice

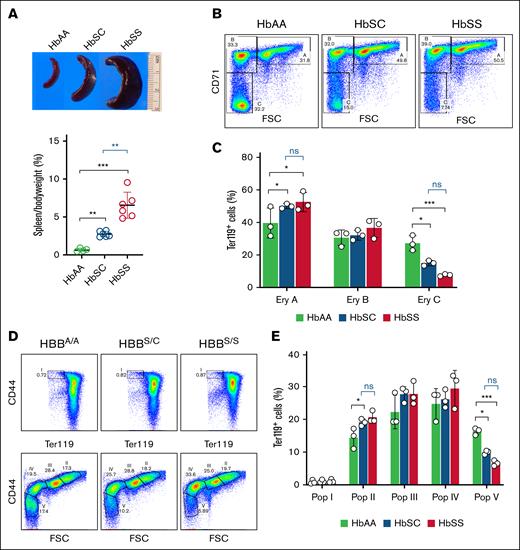

Spleen mass-to–body weight ratios were elevated in both HbSC and HbSS mice, although to a greater extent in the latter (2.75% ± 0.38% vs 6.55% ± 1.71%; Figure 3A), which contrasts with findings in human patients. We used flow cytometry to analyze the maturation of Ter119+ bone marrow erythroid precursors according to CD71 expression and forward scatter25 (Figure 3B). Both HbSC and HbSS mice showed impaired erythroid maturation, with increased proportions of early erythroid precursors and reduced proportions of late precursors (Figure 3C). We obtained similar results using CD44 expression and forward scatter of Ter119+ erythroid precursors as markers for erythroid maturation26 (Figure 3D-E). These findings reflect ineffective erythropoiesis, which is more severe in HbSS disease than HbSC disease.37,38

Ineffective erythropoiesis in HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) Splenomegaly was observed in HbSC and HbSS but not HbAA mice. (B) Representative flow cytometry density plots of bone marrow erythroid cells from HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice analyzed for forward scatter (FSC) and cell surface expression of Ter119 and CD71. Erythroid populations A (Ter119highCD71highFSChigh; basophilic erythroblasts), B (Ter119highCD71highFSClow; late basophilic and polychromatic erythroblasts), and C (Ter119highCD71lowFSClow; orthochromatic erythroblasts and reticulocytes) represent progressively more mature maturation stages. Dead cells, identified by DAPI staining, were excluded. (C) Summary of multiple flow cytometry studies of bone marrow performed as described for panel B. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of bone marrow erythroid precursors stained for Ter119 and CD44. Populations I (proerythroblasts), II (basophilic erythroblasts), III (polychromatic erythroblasts), IV (orthochromatic erythroblasts and reticulocytes), and V (predominantly mature red cells) represent progressively more mature maturation stages. (E) Summary of multiple flow cytometry studies performed as described for panel D (HbAA, n = 3; HbSC, n = 3; HbSS, n = 3). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ery, erythroid; ns, no significance; Pop, population.

Ineffective erythropoiesis in HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) Splenomegaly was observed in HbSC and HbSS but not HbAA mice. (B) Representative flow cytometry density plots of bone marrow erythroid cells from HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice analyzed for forward scatter (FSC) and cell surface expression of Ter119 and CD71. Erythroid populations A (Ter119highCD71highFSChigh; basophilic erythroblasts), B (Ter119highCD71highFSClow; late basophilic and polychromatic erythroblasts), and C (Ter119highCD71lowFSClow; orthochromatic erythroblasts and reticulocytes) represent progressively more mature maturation stages. Dead cells, identified by DAPI staining, were excluded. (C) Summary of multiple flow cytometry studies of bone marrow performed as described for panel B. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of bone marrow erythroid precursors stained for Ter119 and CD44. Populations I (proerythroblasts), II (basophilic erythroblasts), III (polychromatic erythroblasts), IV (orthochromatic erythroblasts and reticulocytes), and V (predominantly mature red cells) represent progressively more mature maturation stages. (E) Summary of multiple flow cytometry studies performed as described for panel D (HbAA, n = 3; HbSC, n = 3; HbSS, n = 3). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001. Ery, erythroid; ns, no significance; Pop, population.

Overlapping and distinct organ pathologies of HbSS and HbSC mice

Both SCD genotypes exhibited similar liver and kidney abnormalities that were more severe in HbSS mice (Table 1). Liver pathologies included extramedullary hematopoiesis, hemosiderosis, hepatocellular necrosis, and sinusoidal dilatation and congestion (supplemental Figure 3). Kidney lesions included vasa recta congestion, glomerular capillary congestion, and tubular iron deposition (supplemental Figure 4). Spleen pathologies in HbSC mice included severe congestion, whereas HbSS mice had moderate congestion and more severe follicular atrophy (supplemental Figure 5). Extramedullary erythropoiesis in livers and spleens was more marked in HbSS mice than HbSC mice, consistent with reduced hemolysis in the latter. Spleens from HbSC mice had a higher density of iron-laden macrophages per unit area, although this does not account for the significantly larger size of HbSS spleens.

Summary and comparison of pathological lesions in the liver, kidney, and spleen of 4-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice

| Organs . | Lesions . | HbAA . | HbSC . | HbSS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | EMH | 1 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Hemosiderophages | 1 | 2 | 2.5 | |

| Sinusoid dilatation with RBCs | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Hepatocellular necrosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Inflammation | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Iron deposition | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Kidney | Glomerular capillary congestion | 1 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Vasa recta congestion | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | |

| Glomerulonephrosis | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Iron stain (tubules) | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | |

| Spleen | Red pulp congestion | 1 | 3.5 | 3 |

| Red pulp erythroid EMH | 1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| White pulp follicular atrophy | 1 | 3 | 3.5 | |

| Iron stain | 1 | 2.5 | 2 |

| Organs . | Lesions . | HbAA . | HbSC . | HbSS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | EMH | 1 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Hemosiderophages | 1 | 2 | 2.5 | |

| Sinusoid dilatation with RBCs | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Hepatocellular necrosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Inflammation | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Iron deposition | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Kidney | Glomerular capillary congestion | 1 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Vasa recta congestion | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | |

| Glomerulonephrosis | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Iron stain (tubules) | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | |

| Spleen | Red pulp congestion | 1 | 3.5 | 3 |

| Red pulp erythroid EMH | 1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| White pulp follicular atrophy | 1 | 3 | 3.5 | |

| Iron stain | 1 | 2.5 | 2 |

Histopathological evaluations of hematoxylin and eosin stains and Prussian blue stains of liver, kidney, and spleen summarized as follows: 1 indicates minimal lesion; 1.5, minimal to mild lesion; 2, mild lesion; 2.5, mild to moderate; 3, moderate; 3.5, moderate to marked lesion; 4, marked lesion. Mice examined were HbAA (n = 4), HbSC (n = 6), and HbSS (n = 6).

EMH, extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Bone pathology is a common clinical manifestation of both HbSS and HbSC diseases.39 We analyzed bone pathologies with DXA and μCT. Femurs from 4-month-old HbSC mice had similar BMD, BV/TV, and cortical wall thickness as HbAA mice, whereas HbSS mice displayed significantly lower BMD and a decreased BV/TV and cortical wall thickness (Figure 4A-C). By 12 months of age, BV/TV and cortical wall thickness reached abnormal levels in HbSC mice (Figure 4B-C). In contrast, the cortical wall thickness was greater at 12 months than 4 months in HbSS mice, although this difference was not significant (P = .3955; Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 6). These results suggest that distinct bone remodeling patterns in HbSC and HbSS disease result in different changes in microarchitecture.

Pathological changes in the femurs of HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) DXA analysis for BMD of femurs from 4-month-old cohort. (B) μCT analysis of femurs from the 4- and 12-month-old cohorts for trabecular BV/TV. (C) μCT analysis of femurs from the 4- and 12-month-old cohorts for cortical wall thickness (4-month-old cohort [HbAA, n = 4; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 3]; 12-month-old cohort [HbAA, n = 6; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 4]). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. ns, no significant difference.

Pathological changes in the femurs of HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) DXA analysis for BMD of femurs from 4-month-old cohort. (B) μCT analysis of femurs from the 4- and 12-month-old cohorts for trabecular BV/TV. (C) μCT analysis of femurs from the 4- and 12-month-old cohorts for cortical wall thickness (4-month-old cohort [HbAA, n = 4; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 3]; 12-month-old cohort [HbAA, n = 6; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 4]). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. ns, no significant difference.

We detected no abnormalities in the retinas of 4-month-old HbSC or HbSS mice (data not shown). Therefore, we examined 12-month-old mice. One eye from each mouse was analyzed by whole-mount immunofluorescence with ICAM2 antibodies to stain blood vessels. In general, HbAA retinas exhibited well-defined major vessels radiating from the optic nerve head and an intact vascular network featuring uniform branching and minimal dropout (Figure 5A, left panel). One HbAA mouse exhibited moderate vascular irregularities. In contrast, HbSC and HbSS retinas exhibited more severe vascular abnormalities, including reduced number of major vessels, abnormal thickness, and central-retinal/midretinal vascular dropout, suggesting compromised vascular integrity and perfusion (Figure 5A, middle and right panels). Retinal vascular pathology was graded by 2 independent retina experts who were blinded to genotypes (R.N.J. and P.M.M.). No significant differences were detected between the SCD groups, although HbSC mice tended to have more severe defects (Figure 5B).

Retinal vascular alterations in HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) Representative whole mount fluorescence images of retinas from 12-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice. HbAA retina (left) showing normal vasculature with well-defined major vessels radiating from the central optic nerve head (orange arrows), uniform branching, and no significant dropout. HbSC and HbSS retinas (middle and right) show reduced numbers of major vessels with irregular thickness (green arrows), peripheral vascular dropout (orange circles), and central-retinal/midretinal vascular dropout (blue circles). Scale bars, 1 mm. (B) Pathological grading on retinal vascular alterations in 12-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice based on vessel morphology, density, and the presence of avascular regions. (C-D) Representative confocal image (C) and reconstructed image generated with an automated pipeline (D) for quantification of retinal vascular branching (scale bar, 100 μm). (E) Quantification of vascular branching in HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice (HbAA, n = 4; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 4). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. ∗P < .05. ns, no significant difference.

Retinal vascular alterations in HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) Representative whole mount fluorescence images of retinas from 12-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice. HbAA retina (left) showing normal vasculature with well-defined major vessels radiating from the central optic nerve head (orange arrows), uniform branching, and no significant dropout. HbSC and HbSS retinas (middle and right) show reduced numbers of major vessels with irregular thickness (green arrows), peripheral vascular dropout (orange circles), and central-retinal/midretinal vascular dropout (blue circles). Scale bars, 1 mm. (B) Pathological grading on retinal vascular alterations in 12-month-old HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice based on vessel morphology, density, and the presence of avascular regions. (C-D) Representative confocal image (C) and reconstructed image generated with an automated pipeline (D) for quantification of retinal vascular branching (scale bar, 100 μm). (E) Quantification of vascular branching in HbAA, HbSC, and HbSS mice (HbAA, n = 4; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 4). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. ∗P < .05. ns, no significant difference.

To assess vascularization more quantitatively, each retina was analyzed in 4 locations with confocal microscopy and image reconstruction (Figure 5C-D). The superior vessels were segmented using DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to identify cellular layers, and branching was scored by automated image analysis. There was a significant increase in vascular branching within HbSC retinas relative to HbAA retinas, but there was no significant difference between HbSS and HbSC retinas (Figure 5E).

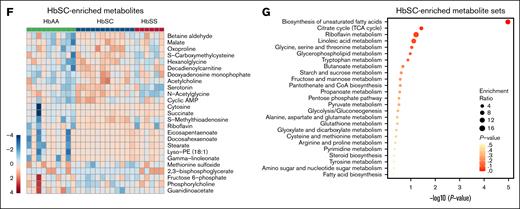

Altered RBC metabolism in HbSC and HbSS mice

RBCs from patients with HbSC or HbSS disease exhibit overlapping and shared metabolic abnormalities.40,41 We used liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry to generate metabolomic profiles of RBCs from 3- to 4-month-old HbAA (n = 10), HbSC (n = 12), and HbSS mice (n = 6).29 Principal component analysis revealed partial clustering of HbSC and HbSS RBC metabolites that differed from HbAA RBCs (Figure 6A). Among 213 RBC metabolites that differed between HbAA and SCD mice, 95 were shared between HbSC and HbSS RBCs (Figure 6B). Heat map analysis highlighted alterations in cytidine, spermine, amino acids (eg, glutamine and alanine), carnitines, and glutathione in HbSC and HbSS RBCs, with more pronounced changes in HbSS RBCs (Figure 6C). These metabolites were enriched in pathways such as pyrimidine, nicotinamide, amino acid, and glutathione metabolism (Figure 6D-E). Furthermore, HbSC and HbSS RBCs each displayed unique metabolite sets associated with the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, the Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle (TCA) cycle, and amino acid metabolism, highlighting genotype-specific metabolic alterations (Figure 6F-G; supplemental Figure 7A-B). Metabolites differentially enriched in HbSC RBCs were primarily associated with amino acid metabolism (arginine, alanine, aspartate, glutamate, and proline), pyrimidine metabolism, and glutathione metabolism (supplemental Figure 8A). Notably, 19 of the 25 top differentially enriched metabolite sets between RBCs from HbSC and HbSS mice differed similarly in patients with the same genotypes40 (supplemental Figure 8B, highlighted in blue), suggesting that Townes HbSS and HbSC mice largely recapitulate genotype-specific metabolic changes observed in patient RBCs.

Metabolic profiles of HbSC and HbSS RBCs. (A) Principal component analysis of metabolomics profiles performed on RBCs from HbAA (n = 10; mixed sex), HbSC (n = 12; mixed sex), and HbSS mice (n = 6; mixed sex). (B) Shared and differentially enriched metabolites in RBCs of HbSC and HbSS mice compared to those in HbAA mice (|fold change| ≥ 1.2; P ≤ .05, by unpaired t test). (C) Heat map showing the top 50 differentially enriched metabolites in RBCs from HbAA (n = 10), HbSC (n = 12), and HbSS mice (n = 6). (D) Heat map showing the top 25 differentially enriched metabolites shared between HbSC and HbSS RBCs compared to HbAA RBCs (|fold change| ≥ 1.2; P ≤ .05, by unpaired t-test). (E) Top metabolite sets associated with shared metabolites in HbSC and HbSS RBCs. The top enriched metabolites sets were identified by metabolite set enrichment analysis using MetaboAnalyst v.5.0. (F) Heat map showing the top 25 differentially enriched metabolites in HbSC RBCs relative to HbSS RBCs compared to HbAA RBCs (|fold change| ≥ 1.2; P ≤ .05, by unpaired t-test). (G) Top metabolite sets associated with HbSC-enriched metabolites.

Metabolic profiles of HbSC and HbSS RBCs. (A) Principal component analysis of metabolomics profiles performed on RBCs from HbAA (n = 10; mixed sex), HbSC (n = 12; mixed sex), and HbSS mice (n = 6; mixed sex). (B) Shared and differentially enriched metabolites in RBCs of HbSC and HbSS mice compared to those in HbAA mice (|fold change| ≥ 1.2; P ≤ .05, by unpaired t test). (C) Heat map showing the top 50 differentially enriched metabolites in RBCs from HbAA (n = 10), HbSC (n = 12), and HbSS mice (n = 6). (D) Heat map showing the top 25 differentially enriched metabolites shared between HbSC and HbSS RBCs compared to HbAA RBCs (|fold change| ≥ 1.2; P ≤ .05, by unpaired t-test). (E) Top metabolite sets associated with shared metabolites in HbSC and HbSS RBCs. The top enriched metabolites sets were identified by metabolite set enrichment analysis using MetaboAnalyst v.5.0. (F) Heat map showing the top 25 differentially enriched metabolites in HbSC RBCs relative to HbSS RBCs compared to HbAA RBCs (|fold change| ≥ 1.2; P ≤ .05, by unpaired t-test). (G) Top metabolite sets associated with HbSC-enriched metabolites.

Discussion

Although HbSC disease appears milder than HbSS disease by some metrics, both genotypes cause multiorgan damage, reduced quality of life, and decreased life span. Moreover, treatment guidelines for HbSC disease are based largely on studies of HbSS disease, despite differences in their pathophysiology. Although mouse models have generated insights into the biology and treatment of HbSS disease, similar models for HbSC disease are lacking. Thus, we sought to develop a mouse model for HbSC disease to facilitate future investigations into its pathophysiology and treatment. We found the humanized HbSC mouse strain described here recapitulates many aspects of human HbSC disease, most importantly marked RBC dehydration, specific organ pathologies, and altered metabolomic profiles.

Both HbSS and HbSC disease cause RBC dehydration. However, this abnormality is more severe with HbSC disease, causing HbS polymerization even with only 1 copy of HbS. Three membrane transport systems contribute to RBC solute loss and dehydration in SCD: Psickle, the Gardos channel, and KCC.42 HbSC RBCs have less Psickle and Gardos channel activity than HbSS RBCs. However, KCC activity is significantly higher in HbSC RBCs, suggesting a prominent role in their relatively severe dehydration.43 Oxygenated HbSC erythrocytes also exhibit increased KCC activity, which is enhanced further by low pH and cell swelling.44,45 More than 20 years ago, Romero et al46 showed that RBCs from transgenic mice expressing human HbC or HbS exhibit KCC abnormalities resembling those in human cells, including stronger activation by HbC. Our study supports and extends these findings by demonstrating that humanized HbSC mice exhibit more severe RBC dehydration than HbSS mice, which imparts unique rheological properties and pathological features.47

Despite progress in the field, the mechanisms for heightened KCC activity in erythroid cells in individuals with HbSC disease still remain unclear. It has been hypothesized that HbC crystals in HbSC erythrocytes reduce soluble Hb levels, mimicking conditions in swollen cells and promoting KCC activation.48 Conversely, potassium efflux in deoxygenated HbSC erythrocytes resembles that found in HbSS cells, with Psickle, KCC, and the Gardos channel all being potential mediators. Our HbSC mouse model offers a valuable new platform to investigate the mechanisms underlying erythrocyte dehydration and shrinkage in HbSC disease, allowing for researchers to evaluate their impact on RBC rheology, hematological parameters, and organ pathologies in vivo.

AVN, osteonecrosis, osteopenia, fragility fractures, and bone pain are common in patients with HbSS or HbSC disease.49,50 Prior studies in 4-month-old male HbSS mice found reduced bone mass and disrupted bone remodeling.51,52 In this study, HbSS and HbSC mice exhibited early-onset low BMD, mirroring findings in preclinical and clinical studies of SCD.53,54 Furthermore, μCT analysis showed loss of trabecular and cortical bone in 4-month-old HbSS and HbSC mice, which worsened in 12-month-old HbSC mice. Somewhat surprisingly, 12-month-old HbSS mice recovered cortical BMD. However, the newly formed bone may be of poor quality55 based on clinical studies showing that individuals with SCD who have normal BMD, which is largely dependent on cortical wall thickness, are at heightened risk of fragility fractures.56-59

Proliferative sickle retinopathy is another major complication of HbSC disease.47,60 In this study, 12-month-old HbSC mice exhibited significant retinal vascular abnormalities, including reduced vessel density, altered vessel morphology, and increased vascular dropout. These findings highlight the potential role of these vascular changes in the retinal complications observed in HbSC disease. However, variability between animals requires a larger sample size to better determine the relative severities of retinal pathology in HbSC mice compared to HbSS mice. One potential explanation for this variability could be the mixed genetic background (B6;129), as susceptibility to eye disease is strain dependent in mice.61-63 Therefore, distinct breeding strategies used by different laboratories to maintain Townes mice could influence SCD pathologies in eyes and other organs. In future studies, it may be possible to exploit the genetic diversity of the Townes strain to discover new modifiers of SCD-associated retinal abnormalities and other phenotypes.64

The major impacts of SCD are not limited to major organs and pathways; a recent study identified significant alterations in the metabolomic profiles of RBCs from patients with HbSC or HbSS disease, with shared and distinct differences between the 2 genotypes.40 Approximately 75% of the top enriched metabolite sets in patients with HbSC or HbSS disease were also enriched in RBCs from the HbSC or HbSS mice described here, highlighting the metabolic relevance of the different mouse models. We found RBCs from both HbSC and HbSS mice exhibited alterations in pyrimidine metabolism, nonessential amino acids, and glutathione metabolism, suggesting that targeting these pathways could enhance RBC metabolism in both SCD mouse models. Further exploration of the mechanisms underlying SCD genotype-specific metabolic alterations will yield a deeper understanding of HbSC and HbSS diseases and may illuminate avenues for the development of targeted therapeutics for human SCD.

In general, the HbSC mice described here recapitulate the unique features of human HbSC disease, including dense, dehydrated erythrocytes with characteristic morphological abnormalities, moderate hemolysis, distinct patterns of organ damage, and metabolomic alterations that distinguish HbSC disease from HbSS disease. However, there are some important differences between HbSC mice and human HbSC disease. First, anemia and hemolysis are more severe in HbSC mice than patients with HbSC disease, who often exhibit minimal anemia and only slightly increased reticulocyte counts. RBCs from HbSC mice have a different HbS:HbC ratio (56.5:43.5) than those from patients with HbSC disease (50:50).12,16 Additionally, HbSC mice exhibit ineffective erythropoiesis, which appears to be minimal in patients with HbSC disease.65 In contrast to human patients, among whom HbSS individuals typically have smaller spleens, HbSC mice exhibit smaller spleens than HbSS mice. We speculate that this is likely because the spleen is a major site of extramedullary erythropoiesis in mice but not humans. Thus, increased spleen mass in HbSS mice likely reflects more accumulated erythroid precursors being produced in response to increased hemolysis and ineffective erythropoiesis than HbSC mice.44,45

While this manuscript was under review, Setayesh et al66 reported the generation of HbSC mice similar to the strain described here. Overall, these mice exhibited similar abnormalities, but there were a few key differences. Notably, we observed decreased mean corpuscular Hb concentration and mean corpuscular volume, whereas Setayesh et al reported increases. In addition, the HbSC mice generated by Setayesh et al showed a stronger propensity for retinal disease than HbSS mice. These differences may stem from technical differences in assays used or from genetic differences related to breeding practices and the mixed genetic background of the Townes mouse. In future studies, it will be interesting to compare the phenotypes of these 2 HbSC strains using the same methodologies.

In summary, this study describes a new HbSC mouse model that replicates key features of human HbSC disease. Most of these features cannot be examined in erythroid cell lines, which do not produce mature RBCs. The HbSC mouse model described here provides physiologically relevant platforms for investigating key aspects of HbSC disease pathophysiology, including KCC activation, erythrocyte dehydration, sickling dynamics, and the systemic manifestations of HbSC disease in vivo. This model, alongside the other recently developed HbSC mouse model, will allow for researchers to examine mechanisms underlying human HbSC disease and guide the development of new targeted therapies for individuals affected by this disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Danny D’Amore for her valuable feedback and insights on the manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health grants U01 HL163983 (M.J.W.), R01 156647 (M.J.W.), and RO1 DK111430 (J.X.), the Assisi Foundation (M.J.W.), the St. Jude Collaborative Research Consortium (S.M.P.-M., M.J.W., and J.S.Y.), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (S.M.P.-M., M.J.W., and J.S.Y.). This research included experiments conducted by the Center for Advanced Genome Engineering, Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Shared Resource, Protein Production Core, and the Genetically Engineered Mouse Model Shared Resource, which are supported in part by the National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA021765.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding bodies.

Authorship

Contribution: J. Zhai, J.B.P., M.J.W., and S.M.P.-M. conceived and designed experiments; J. Zhai, J.B.P., Y.Y., E.D.A., J.Y., T.T., N.G., J.G., D.R.L., R.N.J., J.J., A.K., K.M., J.M., R.R., K.V., H.S.V., and J. Zhang performed experiments; J. Zhai, M.D., P.G.G., H.I.H., L.J.J., P.M.M., M.N., J.X., J.S.Y., Y.Z., M.J.W., and S.M.P.-M. analyzed and interpreted data; M.J.W. and S.M.P.-M. supervised the project; and J. Zhai, M.J.W., and S.M.P.-M. wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.J.W. is a consultant for Fulcrum Therapeutics and an equity owner of Cellarity. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shondra M. Pruett-Miller, Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, MS 340, Memphis, TN 38105; email: shondra.miller@stjude.org; and Mitchell J. Weiss, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, MS 355, Memphis, TN 38105; email: mitch.weiss@stjude.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Shondra M. Pruett-Miller (shondra.miller@stjude.org).

All extended data may be found in a data supplement available with the online version of this article. Software and tools to perform vasculature and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) analysis are available through GitHub (https://github.com/stjude/Retinal_Analysis_Vas).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Pathological changes in the femurs of HbSC and HbSS mice. (A) DXA analysis for BMD of femurs from 4-month-old cohort. (B) μCT analysis of femurs from the 4- and 12-month-old cohorts for trabecular BV/TV. (C) μCT analysis of femurs from the 4- and 12-month-old cohorts for cortical wall thickness (4-month-old cohort [HbAA, n = 4; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 3]; 12-month-old cohort [HbAA, n = 6; HbSC, n = 4; HbSS, n = 4]). Comparisons to HbAA mice are indicated in black; comparisons between HbSC and HbSS mice are indicated in blue. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. ns, no significant difference.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/23/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016793/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016793-gr4.jpeg?Expires=1768380861&Signature=X7wB7UP7mTd9E9OV9AxQdqGR-i2cIizaUmsBCISp8rxZV0VUlNE4j8NopkTcPuaugznr6NVwq3mdIl01dQ8wNBUD385yt0LV-H0lIH0Y-8fs0Kw-TGv~tW8JK~Zf5NNPcTkalNOoFLozPyXO78llUbY5ydw9ofBNlO7sL9s5Ocfds6waJ7Jxi9PadApxw8nLRLulBNhzERaRkTRn4-CdiYOFz0r72AOheRHba-Y5hb2vQiNj9ZNHC2aqxv-j5Of5IE4h4I70d7RGr4RejMe1KPIHJznWtHSdYulcXGe9MOzYB4GvGPZPCHlx6fpQ50SF2TiDG3K6BKDWJup6XbHzLw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)