Key Points

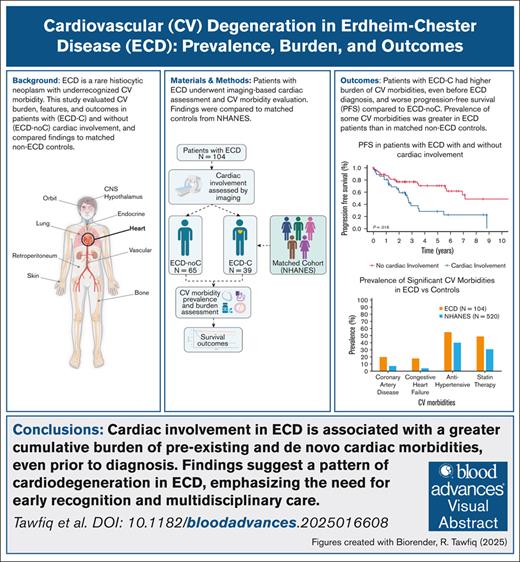

Patients with ECD-C had more CV morbidities, even before diagnosis, than those without and a matched cohort.

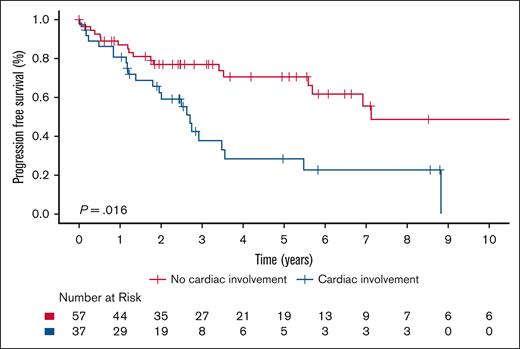

Patients with ECD-C had shorter PFS from frontline therapy than those without, but targeted therapy improved outcomes.

Visual Abstract

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is a rare systemic histiocytic neoplasm, with cardiac morbidities, including cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and cardiac conditions, playing a significant yet poorly understood role in the disease burden. This study evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and prognosis of ECD in patients with (ECD-C) and without cardiac involvement (ECD-noC) and compared the burden of cardiac morbidities with matched controls. Patients diagnosed with ECD between 1990 and 2021 at a tertiary center were included, with cardiac involvement centrally assessed using radiographic studies. Cardiac morbidities were compared with a control group without ECD, matched for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking history. Among 104 patients with ECD, 39 (37%) had cardiac involvement. Patients with ECD-C had higher rates of hypertension (67% vs 46%), hyperlipidemia (67% vs 40%), heart failure (36% vs 8%), and pericardial effusion (28% vs 2%) than those with ECD-noC. Compared with the matched non-ECD cohort, patients with ECD had higher prevalence of coronary artery disease (20% vs 7%), heart failure (18% vs 4%), and antihypertensive drug use (55% vs 40%). Notably, patients with ECD-C had inferior progression-free survival (PFS) from frontline therapy compared with patients with ECD-noC (5-year PFS, 28.3% vs 70.5%). These findings highlight the burden of CV risk factors and cardiac conditions in ECD, even without a clinical diagnosis of ECD-C. Importantly, this cardiac morbidity burden is substantial for patients with ECD-C compared with ECD-noC. Our findings highlight the need for comprehensive cardiac risk assessment and management strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is a rare systemic histiocytic neoplasm. It exhibits a histopathology characterized by the infiltration of various organs by clonal histiocytes often with a foamy cytoplasm, accompanied by fibrosis and inflammation.1 ECD manifests through a multifaceted clinical presentation ranging from fatigue and bone pain to more complex manifestations, such as diabetes insipidus/arginine-vasopressin deficiency, panhypopituitarism, cerebral and cerebellar diseases, cardiac and pulmonary diseases, renal failure, and retroperitoneal and mediastinal fibrosis.2

On the basis of the data presented at the 40th annual meeting of the histiocyte society, the incidence rate of ECD in the United States was 0.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.2-5.2) per 10 million.3 ECD is primarily a disease of middle-aged adults with a male predominance.4,5 Approximately 80% of cases have clonal alterations in genes encoding components of the MAPK signaling pathway (most of which are BRAFV600E and MAP2K), and 10% have variants in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase–protein kinase B signaling pathway.2,6 Cardiac involvement in ECD (ECD-C) has been associated with BRAFV600E mutation.7

ECD-C often remains clinically silent but is prevalent in ∼40% to 50% of patients as detected through computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7-9 Most common findings include pericardial infiltration with effusion (which may be complicated by tamponade) and myocardial infiltration in the form of right atrioventricular pseudotumor (40%).4,7 Other clinical manifestations of ECD-related cardiac involvement include conduction disorders, valvular heart disease, and coronary artery disease (CAD).7-9

Although ECD-C has been reported, large population studies highlighting the disease manifestations and prognostic outcomes remain limited. Research on how ECD-C affects outcomes and preexisting cardiac morbidities is also scarce. Notably, the burden of cardiac morbidities, including cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and cardiac conditions, in ECD is largely unknown. Furthermore, the infiltrative histiocytes in ECD can cause significant end-organ abnormalities that could be clinically silent in the early stages. One well-recognized entity is neurodegeneration, which is associated with histiocytic neoplasms.10,11 However, the impact of ECD on cardiac morbidities, particularly regarding CV degeneration, remains underexplored.

Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the prevalence, imaging features, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of ECD-C. Specifically, we sought to assess the association, burden, and severity of both preexisting and newly developed cardiac morbidities in patients with ECD-C compared with those without cardiac involvement (ECD-noC). In addition, we aimed to compare the prevalence of cardiac morbidities in patients with ECD with an age-, sex-, body mass index (BMI)–, and smoking history–matched control group without an ECD diagnosis. For this study, we use the term ECD-C to refer exclusively to cardiac involvement identified through imaging. Vascular manifestations of ECD such as coated aorta, renovascular disease, and stroke were not evaluated and are outside the scope of this analysis.

Methods

Population

We retrospectively reviewed and included patients with a diagnosis of ECD from January 1990 to December 2021 who were consecutively seen at Mayo Clinic, Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota. Diagnosis of ECD was based on histopathologic confirmation with immunohistochemistry, clinical, and radiologic correlation, and when available, molecular profiling. Among the cohort, molecular testing was available in 84 patients (81%), with BRAFV600E detected in 62% of those tested. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board under the protocol (17-004541). ECD diagnosis was made through central review by expert pathologist (K.R.) and radiologist (J.R.Y.) based on typical clinical and radiologic presentation with pathologic confirmation.2

Assessment of cardiac morbidities

In this study, cardiac morbidities are used as a descriptive term encompassing CV risk factors, such as hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLD), and diabetes, and cardiac disease manifestations or conditions, including CAD, myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), pericardial effusion, valvular disease, and conduction disorders. CV risk factors and cardiac conditions were analyzed and reported separately where applicable to preserve interpretive distinction and avoid causal inference.

Cardiac morbidities were captured before and after ECD diagnosis using Mayo Data Explorer, a Mayo Clinic–developed, self-service data exploration website application that allows users to browse available data collections and elements, such as International Classification of Diseases diagnosis codes and documentation, from clinical notes for specific diagnoses or objective and diagnostic findings. The source system includes >30 years of electronic medical record systems. Patients were classified as having the aforementioned cardiac morbidities before their ECD diagnosis if it was documented in their records before the date of the ECD diagnosis. Conversely, cardiac morbidities were considered to have occurred after the ECD diagnosis if they were identified between the date of the ECD diagnosis and the last follow-up date.

To further assess the burden of cardiac morbidity, we evaluated the timing and severity of each CV risk factor and cardiac condition. This analysis focused on 8 prespecified cardiac morbidities known to have direct structural and functional implications on the heart. We specifically focused on CV risk factors such as HTN and cardiac conditions such as CAD, MI, CHF, atrial fibrillation, pericardial effusion, valvular disease, and conduction disorders (supplemental Table 1). HTN was captured if the patient had the documented diagnosis or the patient had a blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg on 2 separate occasions 4 weeks apart. Conduction disorders were either a diagnosis of first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, sinus bradycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, right bundle branch block, or left bundle branch block.

For each patient, we determined whether these morbidities were present before ECD diagnosis or developed after ECD diagnosis, based on the presence of a documented diagnosis in the medical record as previously described. A Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0–based grading system was created and used to assess the severity of the cardiac morbidities. The grades were mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe (grade 3), and life-threatening or disabling (grade 4). If a condition was present before diagnosis, it was graded accordingly and reassessed after diagnosis if there was evidence of progression. Newly developed conditions were graded at the time of emergence. For each time point, before and after ECD diagnosis, all 8 cardiac morbidities were assessed, and the highest individual grade among them was recorded as the highest severity grade for that time point.12 Cumulative burden was also assessed by counting the number of cardiac morbidities present before and after diagnosis. If a morbidity was present both before and after diagnosis, it contributed to both time points, although the grade was updated if it had progressed. Therefore, the overall burden of cardiac morbidity was determined by both the total number of cardiac morbidities and the highest severity grade at each time point.

Furthermore, we sought to determine whether a diagnosis of ECD, regardless of cardiac involvement, is associated with an increased prevalence of cardiac morbidities compared with individuals without an ECD diagnosis. The prevalence of HTN, CAD, MI, CHF, diabetes, use of antihypertensives, and statin therapy was analyzed compared with a presumed ECD-free matched cohort of patients using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database. Although some definitions of CAD include any history of MI, this was not the case in either the ECD or NHANES data sets. In both cohorts, there were patients with a history of MI who were not classified as having CAD. Given this, we opted to analyze these events separately.

All patients are from the United States of America, and the time used for the NHANES data set was from 2017 to prepandemic 2020. NHANES is a program conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States.13 It is designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the country through surveys and physical examinations. The data obtained for this study were based on surveys conducted by patients in their homes. For each patient with ECD, 5 NHANES respondents were selected, matching exactly on age, sex, BMI group (normal <25 kg/m2, overweight 25-30 kg/m2, obese >30 kg/m2), and smoking history.

Radiological evaluation of cardiac involvement

A board-certified nuclear radiologist (J.R.Y.) with extensive experience as a member of a multidisciplinary group focused on histiocytic disorders performed a comprehensive imaging review of each patient, reviewing all clinical images, including all available modalities and time points that included the heart.14 Cardiac involvement was diagnosed using either cardiac MRI, cardiac CT, or positron emission tomography (PET-CT). All imaging examinations were performed under standard clinical protocols. The radiologist’s expert opinion determined cardiac involvement by ECD and only recorded when unequivocal evidence of cardiac involvement was found through cardiac MRI, cardiac CT, or PET-CT. The location of cardiac involvement was categorized as pericardial, myocardium (left ventricle, right ventricle, left atrium, and right atrium), and coronary artery involvement. For clarity, the designation ECD-C in this study was based strictly on radiologic evidence of cardiac involvement (pericardial, myocardial, or coronary artery) and did not include vascular involvement, such as coated aorta, renovascular disease, and cerebrovascular involvement.

Mutational status

Tumor next-generation sequencing using the 648-oncogene Tempus xT assay (Tempus, Chicago, IL) at diagnosis captured the mutation status for patients with ECD.15 A BRAFV600E/K allele-specific polymerase chain reaction–based assay assessed tumor DNA for the presence of the BRAFV600E mutation when applicable. The complete list of genes included in the Tempus xT panel is available in the supplemental Appendix.

Treatment

First-line treatment was collected for all patients who received the treatment. The therapy type was then categorized into conventional or targeted therapy. Conventional therapy for patients with ECD was defined as treatment with interferon alfa or pegylated interferon alfa, cytokine-directed therapy (eg, anakinra, infliximab), cytotoxic chemotherapy (eg, cladribine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, vinorelbine, vinblastine, hydroxyurea, intra-arterial melphalan), corticosteroids (eg, prednisone), or other therapies (eg, tamoxifen, pembrolizumab, radiation, and surgery). Targeted therapy included BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib), MEK inhibitors (cobimetinib, trametinib), and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib). If the patient received both therapy types in the first line, they were included in both groups.

Statistical and survival analysis

Survival analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of cardiac involvement on progression-free survival (PFS) from frontline treatment and overall survival (OS) in patients with ECD. To assess the impact of cardiac involvement on treatment outcomes, survival analysis was performed within each therapy group (conventional and targeted) to compare PFS between ECD-C vs ECD-noC.

In addition, to determine whether the therapy type provided a survival advantage in both patient populations, PFS was evaluated within each subgroup (ECD-C and ECD-noC) based on therapy type (conventional vs targeted). If a patient had received both conventional and targeted therapies in the first line, they were excluded from the analysis.

To assess the impact of CV risk factors and cardiac conditions on outcomes, we analyzed PFS after frontline therapy in patients with ECD, comparing those with preexisting CV risk factors or cardiac conditions at diagnosis to those who developed them de novo after diagnosis, regardless of cardiac involvement. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using Fisher exact test. Continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared using the Wilcoxon ranked sum test. Survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the overall association between survival and cardiac involvement was done using Cox proportional hazards analysis. OS was calculated from diagnosis to death. PFS was calculated from the start date of first-line therapy to the time of death or disease progression. Results were considered statistically significant if P value < .05. Statistical analysis was performed using R Statistical Software, version 4.2.2.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota (institutional review board 17-004541). This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Study population

In total, 104 patients were included. The median age at diagnosis of ECD was 58 years (IQR, 49-67) for the entire cohort, and 61% were males. ECD-C was found in 39 patients (37%). The median follow-up for ECD-C and ECD-noC was 4.2 years (95% CI, 3.5-6.1) and 4.1 years (95% CI, 3.2-6.5), respectively. The prevalence of smoking was similar between patients with ECD-C and patients with ECD-noC (44% vs 32%; P = .052). Mutation analysis was available for 84 patients (81%), and BRAFV600E mutation was detected in 52 of these patients (62%). BRAFV600E was detected in 26 (79%) of the 33 tested patients with ECD-C vs 26 (51%) of 51 tested patients with ECD-noC (P = .012). The characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| . | All . | ECD-noC . | ECD-C . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 104 (100) | 65 (63) | 39 (37) | |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 58 (49-67) | 57 (46-67) | 60 (54-66) | .14 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 41 (39) | 27 (42) | 14 (36) | .68 |

| BRAFV600E assessed, n (%) | 84 (81) | 51 (78) | 33 (85) | .61 |

| BRAFV600E detected, n (%) | 52 (62) | 26 (51) | 26 (79) | .012 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 33 (32) | 16 (25) | 17 (44) | .052 |

| Presenting with cardiac symptom, n (%) | 15 (14) | 2 (3) | 13 (33) | <.001 |

| Diabetes insipidus, n (%) | 52 (50) | 32 (49) | 20 (51) | 1.00 |

| ECD organ involvement, n (%) | ||||

| Bone | 74 (71) | 48 (74) | 26 (67) | .50 |

| CNS | 38 (37) | 27 (42) | 11 (28) | .21 |

| Ocular | 16 (15) | 6 (9) | 10 (26) | .046 |

| Aorta | 12 (12) | 5 (8) | 7 (18) | .13 |

| Renal | 24 (23) | 14 (22) | 10 (26) | .64 |

| Perirenal | 14 (13) | 7 (11) | 7 (18) | .38 |

| Retroperitoneal | 16 (15) | 8 (12) | 8 (21) | .28 |

| Cardiac tamponade, n (%) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | .050 |

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 12 (12) | 1 (2) | 11 (28) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 12 (12) | 4 (6) | 8 (21) | .053 |

| First-degree AV block, n (%) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | .006 |

| Sinus bradycardia, n (%) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | .018 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | .38 |

| Right bundle branch block, n (%) | 7 (7) | 3 (5) | 4 (10) | .42 |

| Left bundle branch block, n (%) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1.00 |

| CV comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Obesity (BMI, >30 kg/m2) | 28 (27) | 18 (28) | 10 (26) | 1.00 |

| HLD | 52 (50) | 26 (40) | 26 (67) | .015 |

| HTN | 56 (54) | 30 (46) | 26 (67) | .046 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (22) | 12 (18) | 11 (28) | .33 |

| CHF, n (%) | 19 (18) | 5 (8) | 14 (36) | <.001 |

| CAD, n (%) | 21 (20) | 12 (18) | 9 (23) | .62 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 12 (12) | 4 (6) | 8 (21) | .053 |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 51 (49) | 25 (38) | 26 (67) | .008 |

| Antihypertensive therapy, n (%) | 57 (55) | 32 (49) | 25 (64) | .16 |

| . | All . | ECD-noC . | ECD-C . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 104 (100) | 65 (63) | 39 (37) | |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 58 (49-67) | 57 (46-67) | 60 (54-66) | .14 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 41 (39) | 27 (42) | 14 (36) | .68 |

| BRAFV600E assessed, n (%) | 84 (81) | 51 (78) | 33 (85) | .61 |

| BRAFV600E detected, n (%) | 52 (62) | 26 (51) | 26 (79) | .012 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 33 (32) | 16 (25) | 17 (44) | .052 |

| Presenting with cardiac symptom, n (%) | 15 (14) | 2 (3) | 13 (33) | <.001 |

| Diabetes insipidus, n (%) | 52 (50) | 32 (49) | 20 (51) | 1.00 |

| ECD organ involvement, n (%) | ||||

| Bone | 74 (71) | 48 (74) | 26 (67) | .50 |

| CNS | 38 (37) | 27 (42) | 11 (28) | .21 |

| Ocular | 16 (15) | 6 (9) | 10 (26) | .046 |

| Aorta | 12 (12) | 5 (8) | 7 (18) | .13 |

| Renal | 24 (23) | 14 (22) | 10 (26) | .64 |

| Perirenal | 14 (13) | 7 (11) | 7 (18) | .38 |

| Retroperitoneal | 16 (15) | 8 (12) | 8 (21) | .28 |

| Cardiac tamponade, n (%) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | .050 |

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 12 (12) | 1 (2) | 11 (28) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 12 (12) | 4 (6) | 8 (21) | .053 |

| First-degree AV block, n (%) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | .006 |

| Sinus bradycardia, n (%) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | .018 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | .38 |

| Right bundle branch block, n (%) | 7 (7) | 3 (5) | 4 (10) | .42 |

| Left bundle branch block, n (%) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1.00 |

| CV comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Obesity (BMI, >30 kg/m2) | 28 (27) | 18 (28) | 10 (26) | 1.00 |

| HLD | 52 (50) | 26 (40) | 26 (67) | .015 |

| HTN | 56 (54) | 30 (46) | 26 (67) | .046 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (22) | 12 (18) | 11 (28) | .33 |

| CHF, n (%) | 19 (18) | 5 (8) | 14 (36) | <.001 |

| CAD, n (%) | 21 (20) | 12 (18) | 9 (23) | .62 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 12 (12) | 4 (6) | 8 (21) | .053 |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 51 (49) | 25 (38) | 26 (67) | .008 |

| Antihypertensive therapy, n (%) | 57 (55) | 32 (49) | 25 (64) | .16 |

CNS, central nervous system.

Bold indicates statistical significance (2-sided P < .05).

Cardiac imaging findings

Of the patients with ECD-C, 35 (90%) were evaluated by PET-CT, 22 (56%) by cardiac MRI, and 6 (15%) by cardiac CT. Of the 4 patients with ECD-C who did not have a PET-CT (10%), 2 had a cardiac MRI and 2 had a cardiac CT. Table 2 reports the localization of ECD-C. Pericardial involvement was found in 19 patients with ECD-C (49%), of which 11 (58%) had pericardial effusion, with 3 (16%) having cardiac tamponade physiology and 8 (42%) had no documented pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade. Overall, 30 (77%) had myocardial involvement; localized involvement of the right atrium (29 [74%]), left atrium (3 [8%]), right ventricle (2 [5%]), and left ventricle (1 [3%]). Furthermore, 21 patients (54%) had infiltration around the coronary arteries, all of which involved the right coronary, and only 6 (28%) of those 21 patients also had involvement of the left coronary arteries.

Localization of ECD cardiac involvement

| Cardiac layer . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Myocardium | 30 (77) |

| Right atrium | 29 (74) |

| Left atrium | 3 (8) |

| Right ventricle | 2 (5) |

| Left ventricle | 1 (3) |

| Pericardium | 19 (49) |

| Infiltration around coronary arteries | 21 (54) |

| Right coronary | 21 (54) |

| Left coronary | 6 (15) |

| Cardiac layer . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Myocardium | 30 (77) |

| Right atrium | 29 (74) |

| Left atrium | 3 (8) |

| Right ventricle | 2 (5) |

| Left ventricle | 1 (3) |

| Pericardium | 19 (49) |

| Infiltration around coronary arteries | 21 (54) |

| Right coronary | 21 (54) |

| Left coronary | 6 (15) |

Cardiac morbidity prevalence and burden

Table 3 presents the frequency of cardiac morbidities, including CV risk factors and cardiac conditions, among patients with ECD-C compared with patients with ECD-noC before and after ECD diagnosis. Before ECD diagnosis, patients with ECD-C had higher rates of preexisting CV risk factors, such as HTN (59% vs 37%; P = .041), and ECD-related cardiac conditions, such as pericardial effusion (21% vs 2%; P = .002), compared with patients with ECD-noC. After ECD diagnosis, the prevalence of HTN (69% vs 46%; P = .026) and pericardial effusion (28% vs 2%; P < .001) remained high, whereas patients with ECD-C also had increased prevalence of HLD (67% vs 40%; P = .015), CHF (36% vs 8%; P < .001), and valvular heart disease (18% vs 5%; P = .038) compared to patients with ECD-noC.

CV risk factors and cardiac conditions before and after ECD diagnosis

| . | Before ECD diagnosis . | After ECD diagnosis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | |

| CV risk factors, n (%) | ||||||

| Obesity∗ | 23 (54) | 17 (50) | .82 | 26 (61) | 24 (71) | .47 |

| HTN | 24 (37) | 23 (59) | .041 | 30 (46) | 27 (69) | .026 |

| HLD | 20 (31) | 18 (46) | .14 | 26 (40) | 26 (67) | .015 |

| Cardiac conditions, n (%) | ||||||

| CAD | 7 (11) | 8 (21) | .25 | 12 (19) | 9 (23) | .62 |

| MI | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | .064 | 5 (8) | 5 (13) | .50 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (5) | 4 (11) | .42 | 6 (9) | 8 (21) | .14 |

| CHF | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | .15 | 5 (8) | 14 (36) | <.001 |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 (2) | 8 (21) | .002 | 1 (2) | 11 (28) | <.001 |

| Valvular disease | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | .15 | 3 (5) | 7 (18) | .038 |

| Conduction disorder | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | .55 | 5 (8) | 8 (21) | .068 |

| . | Before ECD diagnosis . | After ECD diagnosis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | |

| CV risk factors, n (%) | ||||||

| Obesity∗ | 23 (54) | 17 (50) | .82 | 26 (61) | 24 (71) | .47 |

| HTN | 24 (37) | 23 (59) | .041 | 30 (46) | 27 (69) | .026 |

| HLD | 20 (31) | 18 (46) | .14 | 26 (40) | 26 (67) | .015 |

| Cardiac conditions, n (%) | ||||||

| CAD | 7 (11) | 8 (21) | .25 | 12 (19) | 9 (23) | .62 |

| MI | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | .064 | 5 (8) | 5 (13) | .50 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (5) | 4 (11) | .42 | 6 (9) | 8 (21) | .14 |

| CHF | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | .15 | 5 (8) | 14 (36) | <.001 |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 (2) | 8 (21) | .002 | 1 (2) | 11 (28) | <.001 |

| Valvular disease | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | .15 | 3 (5) | 7 (18) | .038 |

| Conduction disorder | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | .55 | 5 (8) | 8 (21) | .068 |

Bold indicates statistical significance (2-sided P < .05).

BMI was unavailable for 22 patients with ECD-noC and 5 patients with ECD-C, which explains why the percentages are not based on the total number.

After the characterization of each cardiac morbidity, we assessed the cumulative cardiac morbidity disease burden in patients with ECD. Patients with ECD-C exhibited a higher cumulative burden of cardiac morbidities before and after ECD diagnosis (Table 4). Furthermore, patients with ECD-C experienced more severe cardiac morbidity, reaching a highest severity grade of 4, compared with patients with ECD-noC, both before (36% vs 3%; P < .001) and after (46% vs 8%; P < .001) ECD diagnosis. The highest severity grade 4 before ECD diagnosis was predominantly attributed to pericardial effusion (6/14 with ECD-C vs 0/2 with ECD-noC) and CAD (7/14 with ECD-C vs 2/2 with ECD-noC). After ECD diagnosis, pericardial effusion (8/11 with ECD-C vs 0/1 with ECD-noC) and CAD (8/17 with ECD-C vs 5/5 with ECD-noC) continued to be major contributors to the highest severity grade.

Cardiac morbidity burden before and after ECD diagnosis

| . | Before ECD diagnosis . | After ECD diagnosis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | |

| Any CV morbidity present,∗ n (%) | 27 (42) | 28 (72) | .004 | 36 (55) | 33 (85) | .003 |

| Total number of comorbidities, median (IQR) and n (%) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | <.001 | 1 (0-1) | 2 (1-4) | <.001 |

| 0 | 38 (59) | 11 (28) | 29 (45) | 6 (15) | ||

| 1 | 20 (31) | 15 (39) | 21 (32) | 10 (26) | ||

| 2 | 4 (6) | 5 (13) | 7 (11) | 7 (18) | ||

| 3 | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | 4 (6) | 6 (15) | ||

| 4 | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | ||

| 5 | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 5 (13) | ||

| 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | ||

| CV count ≥2, n (%) | 7 (11) | 13 (33) | .009 | 15 (23) | 23 (59) | <.001 |

| CV count ≥3, n (%) | 3 (5) | 8 (21) | .018 | 8 (12) | 16 (41) | .001 |

| CV count ≥4, n (%) | 2 (3) | 4 (10) | .19 | 4 (6) | 10 (26) | .007 |

| Highest severity grade, median (IQR) and n (%) | 0 (0-2) | 2 (0-4) | <.001 | 2 (0-2) | 3 (2-4) | <.001 |

| 0 | 38 (58) | 11 (28) | 29 (45) | 6 (15) | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | ||

| 2 | 20 (31) | 10 (26) | 24 (37) | 8 (21) | ||

| 3 | 5 (8) | 1 (3) | 6 (9) | 4 (10) | ||

| 4 | 2 (3) | 14 (36) | 5 (8) | 18 (46) | ||

| Highest severity grade, n (%) | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| 1-3 | 63 (97) | 25 (64) | 60 (92) | 21 (54) | ||

| ≥4 | 2 (3) | 14 (36) | 5 (8) | 18 (46) | ||

| . | Before ECD diagnosis . | After ECD diagnosis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | P value . | |

| Any CV morbidity present,∗ n (%) | 27 (42) | 28 (72) | .004 | 36 (55) | 33 (85) | .003 |

| Total number of comorbidities, median (IQR) and n (%) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | <.001 | 1 (0-1) | 2 (1-4) | <.001 |

| 0 | 38 (59) | 11 (28) | 29 (45) | 6 (15) | ||

| 1 | 20 (31) | 15 (39) | 21 (32) | 10 (26) | ||

| 2 | 4 (6) | 5 (13) | 7 (11) | 7 (18) | ||

| 3 | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | 4 (6) | 6 (15) | ||

| 4 | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | ||

| 5 | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 5 (13) | ||

| 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | ||

| CV count ≥2, n (%) | 7 (11) | 13 (33) | .009 | 15 (23) | 23 (59) | <.001 |

| CV count ≥3, n (%) | 3 (5) | 8 (21) | .018 | 8 (12) | 16 (41) | .001 |

| CV count ≥4, n (%) | 2 (3) | 4 (10) | .19 | 4 (6) | 10 (26) | .007 |

| Highest severity grade, median (IQR) and n (%) | 0 (0-2) | 2 (0-4) | <.001 | 2 (0-2) | 3 (2-4) | <.001 |

| 0 | 38 (58) | 11 (28) | 29 (45) | 6 (15) | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | ||

| 2 | 20 (31) | 10 (26) | 24 (37) | 8 (21) | ||

| 3 | 5 (8) | 1 (3) | 6 (9) | 4 (10) | ||

| 4 | 2 (3) | 14 (36) | 5 (8) | 18 (46) | ||

| Highest severity grade, n (%) | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| 1-3 | 63 (97) | 25 (64) | 60 (92) | 21 (54) | ||

| ≥4 | 2 (3) | 14 (36) | 5 (8) | 18 (46) | ||

Bold indicates statistical significance (2-sided P < .05).

The CV risk factors and cardiac conditions included for this analysis were the following: HTN, CAD, MI, CHF, atrial fibrillation, pericardial effusion, valvular disease, and conduction disorders.

Subsequently, we looked at the cardiac morbidities in patients with ECD compared with a cohort presumably without a diagnosis of ECD. Patients with ECD in general demonstrate notably higher prevalence rates of CAD (20% vs 7%; P < .001), CHF (18% vs 4%; P < .001), utilization of antihypertensive medications (55% vs 40%; P = .005), and statin therapy (49% vs 31%; P < .001) compared with their matched controls (Table 5). There was no difference in the prevalence of MI, diabetes mellitus, and HTN.

Prevalence of cardiac morbidities in patients with ECD compared with NHANES matched cohort

| . | ECD (n = 104) . | NHANES (n = 520) . | Total (N = 624) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 62 (54, 72) | 62 (54, 72) | 62 (54, 72) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 63 (61) | 315 (61) | 378 (61) | |

| Female | 41 (39) | 205 (39) | 246 (39) | |

| BMI, n (%) | ||||

| Normal | 43 (41) | 215 (41) | 258 (41) | |

| Overweight | 33 (32) | 165 (32) | 198 (32) | |

| Obese | 28 (27) | 140 (27) | 168 (27) | |

| Median (IQR) | 26.7 (23.3, 30.8) | 26.2 (23.4, 30.4) | 26.3 (23.4, 30.4) | .65 |

| CAD, n (%) | 21 (20) | 37 (7) | 58 (9) | <.001 |

| MI, n (%) | 11 (11) | 36 (7) | 47 (8) | .22 |

| CHF, n (%) | 19 (18) | 19 (4) | 38 (6) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 23 (22) | 98 (19) | 121 (19) | .50 |

| HTN, n (%) | 56 (54) | 248 (48) | 304 (49) | .28 |

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 57 (55) | 204 (40) | 261 (42) | .005 |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 51 (49) | 156 (31) | 207 (34) | <.001 |

| . | ECD (n = 104) . | NHANES (n = 520) . | Total (N = 624) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 62 (54, 72) | 62 (54, 72) | 62 (54, 72) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 63 (61) | 315 (61) | 378 (61) | |

| Female | 41 (39) | 205 (39) | 246 (39) | |

| BMI, n (%) | ||||

| Normal | 43 (41) | 215 (41) | 258 (41) | |

| Overweight | 33 (32) | 165 (32) | 198 (32) | |

| Obese | 28 (27) | 140 (27) | 168 (27) | |

| Median (IQR) | 26.7 (23.3, 30.8) | 26.2 (23.4, 30.4) | 26.3 (23.4, 30.4) | .65 |

| CAD, n (%) | 21 (20) | 37 (7) | 58 (9) | <.001 |

| MI, n (%) | 11 (11) | 36 (7) | 47 (8) | .22 |

| CHF, n (%) | 19 (18) | 19 (4) | 38 (6) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 23 (22) | 98 (19) | 121 (19) | .50 |

| HTN, n (%) | 56 (54) | 248 (48) | 304 (49) | .28 |

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 57 (55) | 204 (40) | 261 (42) | .005 |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 51 (49) | 156 (31) | 207 (34) | <.001 |

Bold indicates statistical significance (2-sided P < .05).

First- and second-line treatment

Of the patients from the entire cohort, 94 (90%) received first-line treatment; 37 (95%) were patients with ECD-C and 57 (88%) were patients with ECD-noC (Table 6). The median time from diagnosis to first-line treatment was 56 days (IQR, 22-172); there was no difference in time from diagnosis to first-line treatment between ECD-C and ECD-noC (P = .90). Of those receiving first-line treatment, targeted therapy was received by 44 patients (47%) in the entire cohort; 21 (57%) in patients with ECD-C compared with 23 (40%) in patients with ECD-noC (P = .14).

First- and second-line therapy in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC

| . | ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | Total (N = 104) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line treatment received, n (%) | 57 (88) | 37 (95) | 94 (90) | .31 |

| Targeted therapy | 23 (40) | 21 (57) | 44 (47) | .14 |

| BRAF inhibitor | 14 (25) | 17 (46) | 31 (33) | |

| MEK inhibitor | 8 (14) | 5 (14) | 13 (14) | |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Conventional therapy | 34 (60) | 17 (46) | 51 (54) | .21 |

| IFN-α or PEG–IFN-α | 7 (12) | 8 (22) | 15 (16) | |

| Cytokine-directed therapy | 3 (5) | 2 (5) | 4 (4) | |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | 15 (26) | 8 (22) | 23 (25) | |

| Corticosteroids | 8 (14) | 1 (3) | 9 (10) | |

| Other | 4 (7) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | |

| Second-line treatment received, n (%) | 21 (37) | 17 (46) | 38 (40) | .40 |

| Targeted therapy | 9 (43) | 10 (59) | 19 (50) | .52 |

| BRAF inhibitor | 4 (19) | 9 (53) | 13 (34) | |

| MEK inhibitor | 5 (24) | 2 (12) | 7 (18) | |

| Conventional therapy | 13 (62) | 8 (47) | 21 (55) | .51 |

| IFN-α or PEG–IFN-α | 4 (19) | 1 (6) | 5 (13) | |

| Cytokine-directed therapy | 2 (10) | 4 (24) | 6 (16) | |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | 7 (33) | 2 (12) | 9 (24) | |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) |

| . | ECD-noC (n = 65) . | ECD-C (n = 39) . | Total (N = 104) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line treatment received, n (%) | 57 (88) | 37 (95) | 94 (90) | .31 |

| Targeted therapy | 23 (40) | 21 (57) | 44 (47) | .14 |

| BRAF inhibitor | 14 (25) | 17 (46) | 31 (33) | |

| MEK inhibitor | 8 (14) | 5 (14) | 13 (14) | |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Conventional therapy | 34 (60) | 17 (46) | 51 (54) | .21 |

| IFN-α or PEG–IFN-α | 7 (12) | 8 (22) | 15 (16) | |

| Cytokine-directed therapy | 3 (5) | 2 (5) | 4 (4) | |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | 15 (26) | 8 (22) | 23 (25) | |

| Corticosteroids | 8 (14) | 1 (3) | 9 (10) | |

| Other | 4 (7) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | |

| Second-line treatment received, n (%) | 21 (37) | 17 (46) | 38 (40) | .40 |

| Targeted therapy | 9 (43) | 10 (59) | 19 (50) | .52 |

| BRAF inhibitor | 4 (19) | 9 (53) | 13 (34) | |

| MEK inhibitor | 5 (24) | 2 (12) | 7 (18) | |

| Conventional therapy | 13 (62) | 8 (47) | 21 (55) | .51 |

| IFN-α or PEG–IFN-α | 4 (19) | 1 (6) | 5 (13) | |

| Cytokine-directed therapy | 2 (10) | 4 (24) | 6 (16) | |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | 7 (33) | 2 (12) | 9 (24) | |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) |

Percentages are calculated using the number of individuals who received treatment as the denominator. BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib), MEK inhibitors (cobimetinib, trametinib), tyrosine kinase inhibitor (imatinib), cytokine-directed therapy (anakinra, infliximab), cytotoxic chemotherapy (cladribine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, vinorelbine, vinblastine, hydroxyurea, IA Melphalan), corticosteroid (prednisone), and other (tamoxifen, pembrolizumab, radiation, surgery). Patients may have received >1 treatment type.

IFN-α, interferon alfa; PEG-IFN-α, pegylated interferon alpha.

Furthermore, 38 patients (40%) who received first-line therapy went on to receive second-line therapy (Table 6). Of those who required second-line therapy, the first-line therapy was discontinued in 17 patients (45%) due to disease progression and 14 patients (37%) due to adverse effects. The median time-to-next treatment was 13 months (IQR, 4-36); there was no difference in time to second treatment between ECD-C and ECD-noC (P = .86).

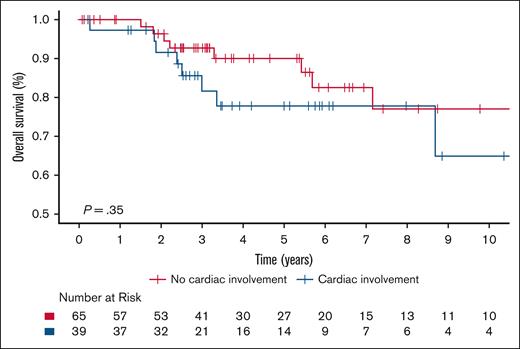

Survival analysis

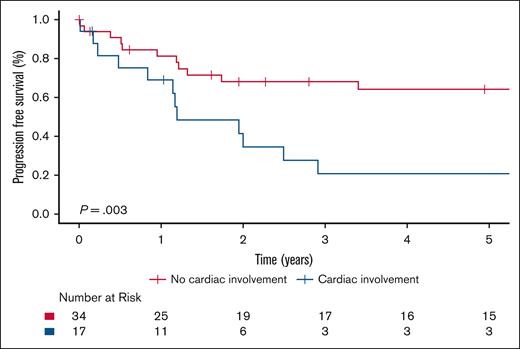

The 5-year OS rate was 85.4% (95% CI, 77.9-93.5) for the entire cohort, and there was no significant difference in OS between ECD-C and ECD-noC (P = .35); 5-year survival estimate for patients with ECD-C was 77.8% (95% CI, 64.4-94.1) compared with 90.1% (95% CI, 82.1-98.9) in patients with ECD-noC (Figure 1). There was a significant difference in PFS from frontline therapy between patients with ECD-C and those with ECD-noC (P = .002). The median PFS of patients with ECD-C was 2.7 years (95% CI, 2.0-5.5) compared to 7.1 years (95% CI, 5.7 to not reached) in patients with ECD-noC; the 5-year PFS estimate for patients with ECD-C was 28.3% (95% CI, 15.0-53.2) compared with 70.5% (95% CI, 58.2-85.5) in patients with ECD-noC (Figure 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating OS in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating OS in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC.

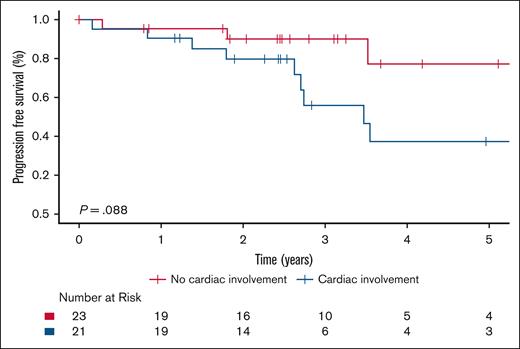

Among those receiving targeted therapy, no significant difference in PFS was observed between ECD-C and ECD-noC (P = .088; Figure 3). In contrast, among patients treated with conventional therapy, PFS was significantly higher in ECD-noC compared with ECD-C (P = .003); the 5-year PFS estimate was 64.1% (95% CI, 49.0-83.8) in ECD-noC vs 20.7% (95% CI, 7.6-56.4) in ECD-C (Figure 4).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC who received targeted therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C and ECD-noC who received targeted therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C and patients with ECD-noC who received conventional therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C and patients with ECD-noC who received conventional therapy.

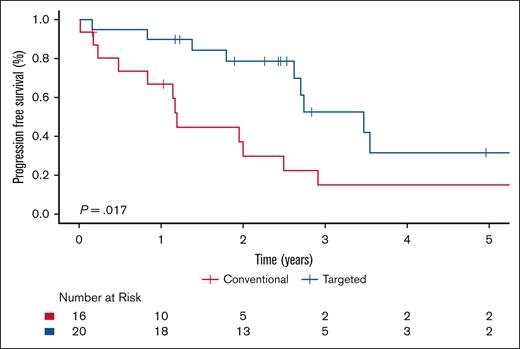

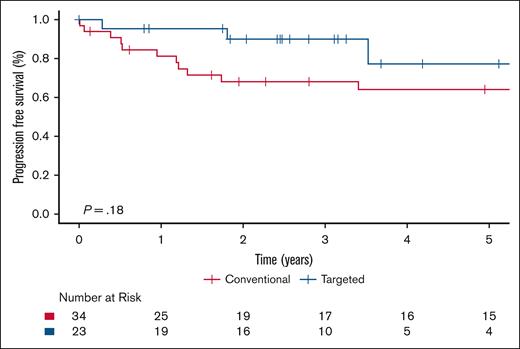

Within the ECD-C cohort, patients who received targeted therapy had significantly improved PFS compared with those treated with conventional therapy (P = .017), with a 5-year PFS estimate of 31.5% (95% CI, 13.0-76.2) for targeted therapy vs 14.9% (95% CI, 4.2-53.1) for conventional therapy (Figure 5). Supplemental Table 2 shows the number of patients with ECD-C and BRAFV600E mutation who received either targeted or conventional therapy in the first-line setting. Among the patients with ECD-C with a BRAF mutation, there was a trend toward improved PFS in those treated with targeted therapy; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .28; supplemental Figure 1). Within the ECD-noC cohort, there was no statistically significant difference in PFS to those treated with conventional therapy compared with targeted therapy (P = .18; Figure 6).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C who received conventional vs targeted therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-C who received conventional vs targeted therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-noC who received conventional vs targeted therapy.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD-noC who received conventional vs targeted therapy.

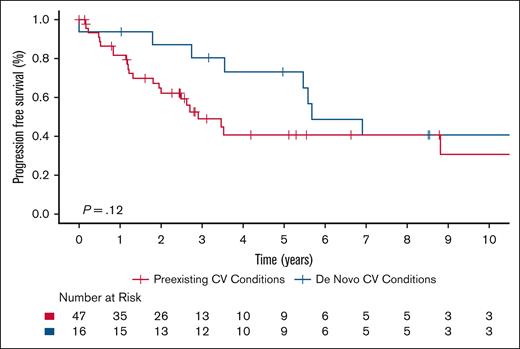

In patients with ECD, regardless of cardiac involvement, those with preexisting CV risk factors or cardiac conditions at diagnosis seemed to have shorter PFS compared with those who developed cardiac morbidities de novo after diagnosis. The 5-year PFS estimate was 40.7% (95% CI, 26.7-62.0) for patients with preexisting cardiac morbidities and 73.1% (95% CI, 53.5-99.7) for those with de novo cardiac morbidities. The hazard ratio for preexisting vs de novo cardiac conditions was 1.90 (95% CI, 0.84-4.30), though this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 7). No significant difference in OS was observed between the groups.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD based on timing of cardiac morbidity (preexisting vs de novo).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating PFS in patients with ECD based on timing of cardiac morbidity (preexisting vs de novo).

Discussion

ECD, as an infiltrative histiocytic malignancy, poses significant risks to cardiac health. Using a large cohort of patients in this study, we found a significant difference in the prevalence of HTN, pericardial effusion, MI, HLD, CHF, and valvular heart disease between ECD-C and ECD-noC. We revealed that cardiac morbidities are significantly more prevalent in patients with ECD-C even before their diagnosis of ECD. In addition, patients with ECD-C exhibited a greater cumulative burden of cardiac disease, with more severe preexisting and de novo cardiac morbidities, compared to patients with ECD-noC. Although our descriptive design does not allow for causal inference, these findings suggest a potential association between ECD pathophysiology and the development or exacerbation of cardiac conditions, even in the absence of overt cardiac involvement of ECD. The concurrent presence of traditional CV risk factors further emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary care throughout the disease course.14

ECD-C more frequently affected the myocardium, with a preference for the right atrium, which is a known site of involvement and a common location for disease-related complications, such as conduction abnormalities.16-18 Additional complications associated with cardiac-involved ECD include pericarditis and cardiac tamponade.19 In this study, patients with ECD-C had a higher frequency of pericardial effusions compared with patients with ECD-noC, attributing to the inherent risk of cardiac-involved disease.20,21

Although the exact reasons for cardiac infiltration, specifically myocardial preference, in ECD are not fully elucidated, several factors have been implicated. For example, elevated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels have been associated with cardiac involvement in patients with ECD. A study found that patients with high serum VEGF levels more frequently had cardiac and vascular involvement, suggesting that VEGF may play a role in the pathophysiology of ECD-C.22

Consistent with prior studies, ECD-C did not significantly affect OS.7,23,24 However, patients with cardiac involvement in general had significantly shorter PFS than those without, regardless of the type of first-line therapy (conventional or targeted) received. We demonstrated a high prevalence of the BRAFV600E mutation in ECD-C, a known phenomenon, with 79% of affected patients testing positive, closely aligning with the 81% reported by Azoulay et al in patients with ECD-C.7 Notably, patients with ECD-C exhibited superior PFS when treated with targeted therapy compared with conventional therapy, an outcome that was not observed in those with ECD-noC. This suggests that patients with ECD-C, whose disease is typically enriched with MAPK pathway alterations, may derive significant benefits from targeted therapy over conventional treatment. However, due to the constraints of a limited sample size, which hindered the ability to detect a significant difference, there was no notable difference in PFS among patients with ECD-C with a BRAFV600E mutation when comparing those treated with targeted therapy vs conventional therapy.

Similar to the established association between neurodegeneration and histiocytic neoplasms, including ECD, our findings suggest that the high prevalence of CV morbidity in patients with ECD may reflect a distinct, disease-specific CV manifestation which could be attributed to CV degeneration associated with ECD.25,26 In this context, we use the term CV degeneration to describe the progressive and multifactorial decline in CV integrity that may result from chronic inflammation, histiocytic infiltration, and coexisting traditional risk factors. This concept reinforces the notion that patients with ECD may be predisposed to a degenerative cascade within the CV system, highlighting the importance of earlier recognition and aggressive management of cardiac morbidities in patients with ECD.

Our study is inherently limited by its retrospective design and the incomplete mutational status data. The retrospective design introduces potential data collection and interpretation biases, such as incomplete or inconsistent patient records. Specialists supervised data collection for patients with ECD, whereas NHANES relied on self-reported surveys, introducing potential recall bias. In addition, the heterogeneity between ECD-C, ECD-noC, and NHANES cohorts prevented direct comparisons and limited our ability to perform adjusted analysis across cohorts. The comparison with NHANES data is based on several key assumptions: first, that the respondents were entirely free from ECD; second, that the surveyed events were accurately interpreted and recalled by the respondents; and third, that the event rates observed during the 2017-2020 survey period were consistent with the time frame in which patients with ECD were diagnosed. In addition, cardiac involvement may be underestimated due to the lack of cardiac MRI or CT imaging in all patients, potentially limiting the accuracy of detection. We also did not assess vascular involvement outside of the coronary arteries due to the absence of standardized radiologic evaluation and structured data capture for vascular features, such as coated aorta, renovascular disease, or cerebrovascular involvement. Last, although clonal hematopoiesis is increasingly recognized with ECD and associated with CV risk, no patients in our ECD cohort had a documented diagnosis, limiting our ability to evaluate its potential impact.27-29

In conclusion, this study provides insights into the cardiac implications of ECD, offering one of the most extensive analyses of cardiac involvement by this infiltrative malignancy. By demonstrating the significant burden of cardiac morbidities in patients with ECD-C and identifying differences in PFS, our findings highlight the impact of cardiac involvement on disease management and patient outcomes. Even before ECD diagnosis, there was a higher prevalence of both CV risk factors and cardiac conditions, emphasizing the importance of early evaluation of cardiac morbidities. These findings support a multidisciplinary approach integrating internal medicine, cardiology, radiology, and pathology specialists to manage these patients. As advancements in treatment prolong patient survival, addressing the cardiac challenges associated with ECD and cardiac morbidities will be essential for improving long-term outcomes and quality of life. Future research should investigate the mechanisms of ECD-induced cardiodegeneration and tailor therapeutic strategies to mitigate its impact.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by the generosity of Kenneth G. Mann and the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Family Foundation. The research was also supported by American Cancer Society award RSG-24-1317006-01-CTPS (G.G.).

A.A.A.-M. serves as cochair for the Mayo Clinic–University of Alabama at Birmingham Histiocytosis Working Group. G.G. is a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Authorship

Contribution: R.K.T. was responsible for data collection and extraction and drafted the manuscript under the close supervision and guidance of G.M.S. and J.P.A.; G.M.S. conducted the statistical analyses and developed the survival figures; J.R.Y. performed the radiographic evaluation to identify cardiac involvement of Erdheim-Chester disease by systematically reviewing the imaging for each patient included in this study; R.K.T. and J.P.A. conceptualized and designed the research; and all authors provided critical revisions and contributed to the final editing and refinement of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.P.A. reports funding for clinical trials from Qurient and Biomed Valley Discoveries. A.A.A.-M. reports travel support from a Histiocyte Society Early Investigator Travel grant and the American Society of Hematology Hematology Opportunities for the Next Generation of Research Scientists Program. G.G. reports consulting fees from Recordati; royalties from UpToDate; and advisory board fees from Opna Bio, Seagen, and Sobi (all unrelated to the content of this article). W.O.T. reports research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Mayo Clinic Center for Multiple Sclerosis and Autoimmune Neurology, and Mallinckrodt Inc; and royalties from the publication of “Mayo Clinic Cases in Neuroimmunology.” T.H. reports research funding to their institution from BeiGene and Bristol Myers Squibb. M.J.K., M.K.M., and K.R. report consulting roles with Amgen, unrelated to the content of this article. M.A.M. reports consulting fees from AbbVie and Genentech, unrelated to the content of this article. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the Histio-Care Network appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Jithma P. Abeykoon, Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 1st St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; email: abeykoon.jithma@mayo.edu; and Gaurav Goyal, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1808 7th Ave S, 813 Boshell Building, Birmingham, AL 35233; email: ggoyal@uabmc.edu.

Appendix

The members of the Histio-Care Network are Jithma P. Abeykoon, Grant M. Spears, Jason R. Young, W. Oliver Tobin, Dongni Yi, Karen Rech, Matthew J. Koster, Aldo A. Acosta-Medina, Lucinda Gruber, Aishwarya Ravindran, Mithun Vinod Shah, N. Nora Bennani, Muhamad Alhaj Moustafa, Talal Hilal, Julio C. Sartori Valinotti, Robert Vassallo, Jay H. Ryu, Caroline Davidge-Pitts, Surendra Dasari, Thomas E. Witzig, Ronald S. Go, Corrie R. Bach, Gaurav Goyal, Rebecca King, Carla Borre, Mia Poleksic, Asra Ahmed, and Sam Reynolds.

References

Author notes

Deidentified data not published within this article will be made available to any qualified investigator upon request from the corresponding authors, Jithma P. Abeykoon (abeykoon.jithma@mayo.edu) and Gaurav Goyal (ggoyal@uabmc.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.