Key Points

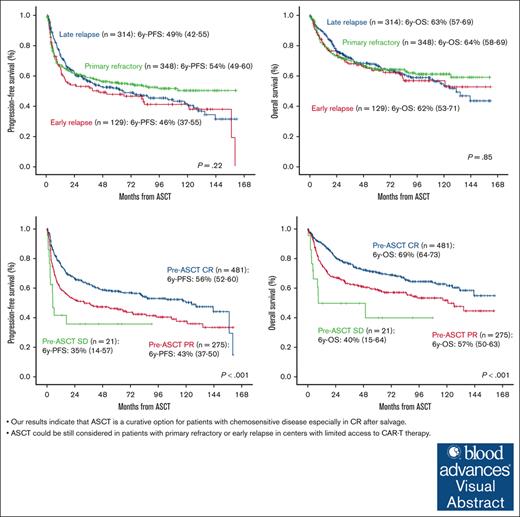

Our results indicate that ASCT is a curative option for patients with chemosensitive disease especially in CR after salvage.

ASCT could still be considered in patients with primary refractory or early relapse in centers with limited access to CAR-T therapy.

Visual Abstract

We performed a retrospective multicenter study including 791 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) who underwent autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). After a median follow-up of 74 months from infusion, 65% were alive and 84% free of disease. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) at 6 years were 51% and 63%, respectively. Non-relapse mortality at 1 year was 9%. Age >60 years at ASCT (hazard ratio [HR], 1.31; 95% CI, 1.06-1.62; P = .011), ASCT as ≥3rd line (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.42-2.31; P < .001), and partial response (PR) vs complete response (CR) at ASCT (HR, 1.46; 95% CI. 1.18-1.81; P < .001) were independent variables influencing PFS. Age >60 years at ASCT (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.24-2.12; P < .001), time period before 1 November 2012 (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.07-1.83; P = .014), ASCT as ≥3rd line (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.32-2.37; P < .001), PR vs CR (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.22-2.05; P < .001), and stable disease vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 3.41; 95% CI, 1.81-6.45; P < .001) were variables associated with worse OS. Refractory/early relapse did not significantly influence survival (6-year PFS and OS in patients with refractory, early, and late relapse were 54% and 64%, 46% and 62%, and 49% and 63%, respectively). To our knowledge, this is the largest series analyzing the efficacy of ASCT in patients with R/R LBCL after rituximab-containing frontline therapy. Our results indicate that ASCT is a curative option for patients with chemosensitive disease.

Introduction

Large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) are a heterogeneous group of aggressive BCL and the most common subtype. The prognosis depends on various clinical and molecular factors. Despite the fact that standard frontline treatment is highly successful, there is still ∼30% to 40% of the patients who will be primary refractory or will relapse, and these patients are characterized by poor outcome. Until very recently, high-dose therapy (HDT) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has remained the treatment of choice for transplant-eligible patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) LBCL responding to platinum-based salvage chemoimmunotherapy.1,2 PARMA trial, conducted before the rituximab era, revealed that this strategy resulted in a higher event-free survival (EFS) compared with the continuation of salvage chemotherapy alone in patients who achieved complete remission (CR) or partial response (PR).3 The most common conditioning regimen used is the BEAM regimen (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan), but no randomized data are available to demonstrate superiority of this regimen.

Although HDT/ASCT is still considered an option for sensitive R/R LBCL, only half of the patients are able to proceed to this approach because of age and/or comorbidities. Nevertheless, only ∼35% to 50% of patients who received the salvage treatment will achieve PR or CR and will finally receive the ASCT.4-6

Recently, autologous CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has been approved in second line for patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse (<1 year of first-line therapy), based on the results of ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM trials, which demonstrated significantly better EFS of CAR-T therapy compared with salvage treatment followed by HDT/ASCT.7-9 Therefore, nowadays, it is considered the treatment of choice for second line, and the current role of ASCT has been questioned. Our objective was to analyze the efficacy of ASCT after a long-term follow-up in patients with R/R LBCL who had received rituximab and anthracycline–based frontline therapy and try to define the optimal role of ASCT.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

We performed a retrospective multicenter study based on patients registered in the Grupo Español de Trasplante y Terapia Celular (GETH-TC) database of ASCT. We included patients from centers of GETH-TC/Grupo Español de Linfoma y Trasplante Autólogo with R/R LBCL who underwent ASCT from January 2010 to December 2021 and had received rituximab and anthracycline–based frontline therapy. Diffuse LBCL not otherwise specified (NOS), high-grade BCL double/triple hit and NOS, primary mediastinal, transformed follicular lymphoma, and other less frequent LBCL subtypes were included. Plasmablastic and primary central nervous system lymphomas were excluded. Patients who underwent ASCT in first CR or PR were also excluded except patients with transformed follicular lymphoma who had received previous anthracycline-based frontline therapy for the indolent lymphoma. The histological diagnosis was based on the local assessment, and patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor system. Disease status pre-ASCT was assessed by the local team according to Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma10 and/or Lugano Classification,11 defined as CR, PR, and refractory disease (stable disease [SD] or progression). The primary end points were PFS and OS in the overall series according to different prognostic factors, including patient’s characteristics at diagnosis, response after front line, disease status at salvage therapy, type of second-line therapy, conditioning regimen, and disease status at ASCT and separately in the subgroup of patients with primary refractory disease and early relapse. Refractory disease was defined as progression or no response to first-line treatment, early relapse from CR ≤12 months after the completion of first-line chemoimmunotherapy, and late relapse >12 months. Cumulative incidences (CIs) of relapse and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) were also analyzed. The study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by research ethic committee of Son Espases University Hospital. As part of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) registration, all patients signed informed consent.

Outcome measures

All outcome measures were assessed from the time of ASCT. PFS was defined as the time from transplantation to disease progression or death of any cause. OS was defined as the time from ASCT to death from any cause, and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. NRM was defined as the time from ASCT to death without previous disease relapse or progression. CI of relapse was defined as the time from ASCT to relapse or progression.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative or binomial variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between qualitative variables were done using the Fisher exact test or chi square. The binary logistic regression was used to find out the risk factors associated with NRM. Time-to-event variables were estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between variables of interest were performed by the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis with the variables that appeared to be significant in the univariate analysis was carried out according to the Cox proportional hazard regression model. To analyze the impact of time period on survival, we used the MAXTAT package on R. All P values reported were 2-sided, and statistical significance was defined at P < .05.

Results

A total of 791 patients diagnosed with having LBCL (68% diffuse LBCL NOS; 57% male; median age at ASCT: 56 years [range, 18-76]) were included from the GETH-TC registry. Patients’ characteristics at diagnosis and at ASCT are summarized in Table 1. Median time between diagnosis and ASCT was 15.4 months (range, 3.2-318.5). Furthermore, 40% of the patients had primary refractory disease pre-ASCT, 16% experienced early relapse, and 40% late relapse.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics at diagnosis . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis (range), y | 54 (17-74) |

| Sex (M/F), (%) | 450 (57%)/341 (43%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| DLBCL NOS | 540 (68%) |

| HGBCL DH/TH | 32 (4%) |

| HGBCL NOS | 27 (3%) |

| PMLBCL | 55 (7%) |

| Transformed FL | 76 (10%) |

| DLBCL gray zone | 18 (2%) |

| DLBCL T-cell rich | 20 (2%) |

| Other | 8 (1%) |

| Missing | 15 (2%) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |

| I-II | 168 (21%) |

| III-IV | 606 (77%) |

| Missing | 17 (2%) |

| B symptoms | |

| No | 405 (51%) |

| Yes | 354 (45%) |

| Missing | 32 (4%) |

| Bulky disease | |

| No | 504 (64%) |

| Yes | 241 (30%) |

| Missing | 46 (6%) |

| Extranodal involvement | |

| No | 286 (36%) |

| Yes | 464 (59%) |

| Missing | 41 (5%) |

| R-IPI | |

| 0 | 42 (5%) |

| 1-2 | 329 (42%) |

| 3-5 | 346 (44%) |

| Missing | 74 (9%) |

| Response after front line | |

| CR | 443 (56%) |

| PR | 154 (19%) |

| SD | 45 (6%) |

| PD | 149 (19%) |

| Characteristics at ASCT | N (%) |

| Median age at ASCT (range), y | 56 (18-76) |

| Disease status at salvage therapy | |

| Late relapse | 314 (40%) |

| Early relapse | 128 (16%) |

| Primary refractory | 349 (44%) |

| Second-line therapy | |

| R-ESHAP | 442 (56%) |

| R-DHAP | 48 (6%) |

| R-ICE | 41 (5%) |

| R-GDP | 38 (5%) |

| Other | 195 (25%) |

| Missing | 27 (3%) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| BEAM | 628 (79%) |

| R-BEAM | 75 (10%) |

| Z-BEAM | 19 (2%) |

| Other | 53 (7%) |

| Missing | 16 (2%) |

| Treatment line at ASCT | |

| Second line | 617 (78%) |

| Third line | 147 (19%) |

| Front line in transformed | 27 (3%) |

| Disease status at ASCT | |

| CR | 481 (61%) |

| PR | 275 (35%) |

| SD | 21 (3%) |

| Not evaluated | 14 (2%) |

| Characteristics at diagnosis . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis (range), y | 54 (17-74) |

| Sex (M/F), (%) | 450 (57%)/341 (43%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| DLBCL NOS | 540 (68%) |

| HGBCL DH/TH | 32 (4%) |

| HGBCL NOS | 27 (3%) |

| PMLBCL | 55 (7%) |

| Transformed FL | 76 (10%) |

| DLBCL gray zone | 18 (2%) |

| DLBCL T-cell rich | 20 (2%) |

| Other | 8 (1%) |

| Missing | 15 (2%) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |

| I-II | 168 (21%) |

| III-IV | 606 (77%) |

| Missing | 17 (2%) |

| B symptoms | |

| No | 405 (51%) |

| Yes | 354 (45%) |

| Missing | 32 (4%) |

| Bulky disease | |

| No | 504 (64%) |

| Yes | 241 (30%) |

| Missing | 46 (6%) |

| Extranodal involvement | |

| No | 286 (36%) |

| Yes | 464 (59%) |

| Missing | 41 (5%) |

| R-IPI | |

| 0 | 42 (5%) |

| 1-2 | 329 (42%) |

| 3-5 | 346 (44%) |

| Missing | 74 (9%) |

| Response after front line | |

| CR | 443 (56%) |

| PR | 154 (19%) |

| SD | 45 (6%) |

| PD | 149 (19%) |

| Characteristics at ASCT | N (%) |

| Median age at ASCT (range), y | 56 (18-76) |

| Disease status at salvage therapy | |

| Late relapse | 314 (40%) |

| Early relapse | 128 (16%) |

| Primary refractory | 349 (44%) |

| Second-line therapy | |

| R-ESHAP | 442 (56%) |

| R-DHAP | 48 (6%) |

| R-ICE | 41 (5%) |

| R-GDP | 38 (5%) |

| Other | 195 (25%) |

| Missing | 27 (3%) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| BEAM | 628 (79%) |

| R-BEAM | 75 (10%) |

| Z-BEAM | 19 (2%) |

| Other | 53 (7%) |

| Missing | 16 (2%) |

| Treatment line at ASCT | |

| Second line | 617 (78%) |

| Third line | 147 (19%) |

| Front line in transformed | 27 (3%) |

| Disease status at ASCT | |

| CR | 481 (61%) |

| PR | 275 (35%) |

| SD | 21 (3%) |

| Not evaluated | 14 (2%) |

BEAM, BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; F, female; HGBCL, high-grade BCL; M, male; PMLBL, primary mediastinal large BCL; R-BEAM, rituximab-BEAM; R-DHAP, rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin; R-ESHAP, rituximab, etoposide, cytarabine, cisplatin, and methylprednisolone; R-ICE, rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide; R-GDP, rituximab, gemcitabine, cisplatin, and dexamethasone; TEAM, thiotepa, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; Z-BEAM, yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan-BEAM.

Survival analysis

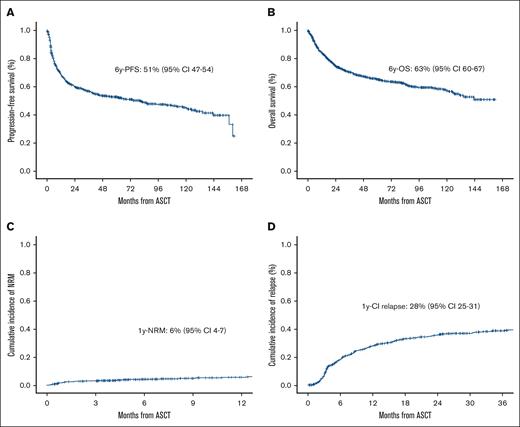

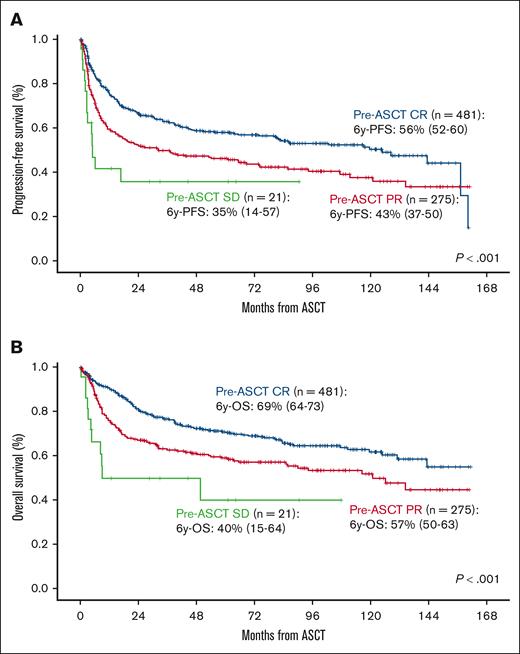

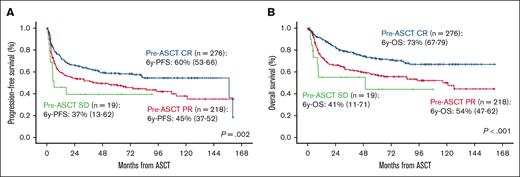

After a median follow-up of 74 months (range, 68-81), 65% of the patients were alive and 84% free of disease. PFS and OS at 6 years were 51% (95% CI, 47-54) and 63% (95% CI, 60-67), respectively (Figure 1A-B). PFS was significantly influenced by age at ASCT, the number of lines before ASCT, and disease status at ASCT (P < .01) (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, age >60 years at ASCT (hazard ratio [HR], 1.31; 95% CI, 1.06-1.62; P = .011), ASCT as more than or equal to third line (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.42-2.31; P < .001), and PR vs CR at ASCT (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.18-1.81; P < .001) were the only independent variables influencing PFS (Table 3; Figure 2A). OS was influenced by age at diagnosis, Revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) at diagnosis, age at ASCT, time period, treatment lines before ASCT, and disease status at ASCT (P < .01; Table 2). Age >60 years at ASCT (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.24-2.12; P < .001), time period before 1 November 2012 (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.07-1.83; P = .014), ASCT as more than or equal to third line (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.32-2.37; P < .001), PR vs CR (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.22-2.05; P < .001), and SD vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 3.41; 95% CI, 1.81-6.45; P < .001) were the only variables associated with worse OS (Table 3; Figure 2B).

Survival, NRM and relapse/progression in the overall series. PFS (A), OS (B), NRM (C), and CI relapse (D) in the overall series.

Survival, NRM and relapse/progression in the overall series. PFS (A), OS (B), NRM (C), and CI relapse (D) in the overall series.

Univariate analysis for OS and PFS in the overall series

| Characteristics at diagnosis . | N . | 6-year PFS (95% CI) . | P value . | 6-year OS (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .20 | .026 | |||

| 17-60 y | 562 | 52% (48-57) | 65% (61-70) | ||

| >60 y | 229 | 47% (40-54) | 58% (51-65) | ||

| Gender | .91 | .93 | |||

| Male | 450 | 51% (46-56) | 63% (58-68) | ||

| Female | 341 | 51% (41-56) | 64% (58-69) | ||

| Diagnosis | .16 | .69 | |||

| DLBCL NOS | 540 | 51% (46-55) | 63% (59-68) | ||

| HG DH/TH | 32 | 42% (24-61) | 62% (43-81) | ||

| HG NOS | 27 | 39% (18-61) | 52% (30-74) | ||

| PMBL | 55 | 63% (50-77) | 67% (54-81) | ||

| Transformed FL | 76 | 36% (24-49) | 57% (44-69) | ||

| DLBCL gray zone | 18 | 64% (41-87) | 82% (63-100) | ||

| DLBCL T-cell rich | 20 | 63% (38-87) | 61% (25-86) | ||

| Other | 8 | 57% (20-94) | 69% (32-100) | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | .86 | .47 | |||

| I-II | 168 | 50% (42-58) | 61% (53-69) | ||

| III-IV | 774 | 51% (47-56) | 64% (60-68) | ||

| B symptoms | .86 | .40 | |||

| No | 405 | 49% (43-54) | 64% (58-69) | ||

| Yes | 354 | 53% (47-58) | 62% (56-67) | ||

| Bulky disease | .4 | .88 | |||

| No | 504 | 49% (44-54) | 63% (59-68) | ||

| Yes | 241 | 54% (47-60) | 63% (56-69) | ||

| Extranodal involvement | .27 | .88 | |||

| No | 286 | 49% (42-55) | 64% (58-70) | ||

| Yes | 464 | 52% (47-57) | 63% (58-67) | ||

| R-IPI | .15 | .015 | |||

| 0 | 42 | 57% (41-73) | 76% (61-91) | ||

| 1-2 | 329 | 52% (46-58) | 67% (62-73) | ||

| 3-5 | 346 | 48% (43-54) | 58% (53-64) | ||

| Response after first line | .23 | .24 | |||

| CR | 443 | 48% (43-53) | 63% (58-68) | ||

| PR | 154 | 54% (45-62) | 65% (57-73) | ||

| SD | 45 | 63% (49-78) | 73% (59-87) | ||

| PD | 149 | 50% (42-59) | 59% (50-68) | ||

| Characteristics at ASCT | N | 6-year PFS (95% CI) | P value | 6-year OS (95% CI) | P value |

| Age at ASCT | .031 | .001 | |||

| 17-60 y | 501 | 54% (50-59) | 67% (63-72) | ||

| >60 y | 290 | 44% (38-51) | 56% (49-62) | ||

| Disease status at salvage therapy | .22 | .85 | |||

| Late relapse | 314 | 49% (42-55) | 63% (57-69) | ||

| Early relapse | 129 | 46% (37-55) | 62% (53-71) | ||

| Primary refractory | 348 | 54% (49-60) | 64% (58-69) | ||

| Time period | .16 | .020 | |||

| Before 30 October 2012 | 163 | 47% (39-54) | 56% (48-64) | ||

| Beyond 1 November 2012 | 628 | 52% (47-56) | 66% (61-70) | ||

| Second-line therapy | .4 | .5 | |||

| R-ESHAP | 442 | 51% (46-56) | 63% (58-68) | ||

| R-DHAP | 48 | 45% (30-59) | 56% (41-71) | ||

| R-ICE | 41 | 65% (50-81) | 75% (60-89) | ||

| R-GDP | 38 | 32% (0-63) | 61% (25-97) | ||

| Other | 195 | 51% (44-59) | 63% (56-71) | ||

| Conditioning regimen | .63 | .97 | |||

| BEAM | 628 | 51% (47-55) | 64% (60-68) | ||

| R-BEAM | 75 | 45% (32-57) | 61% (49-74) | ||

| Z-BEAM | 19 | 47% (22-67) | 58% (36-80) | ||

| TEAM | 4 | 37% (0-93) | 67% (13-100) | ||

| Other | 49 | 62% (48-76) | 66% (52-79) | ||

| Treatment line at ASCT | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Second line | 617 | 56% (52-60) | 68% (64-72) | ||

| Third line | 147 | 33% (25-41) | 45% (36-54) | ||

| Front line in transformed | 27 | 28% (8-47) | 55% (33-76) | ||

| Pre-ASCT response | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| CR | 481 | 56% (52-61) | 69% (64-73) | ||

| PR | 275 | 43% (37-50) | 57% (50-63) | ||

| SD/PD | 21 | 35% (14-57) | 40% (15-64) |

| Characteristics at diagnosis . | N . | 6-year PFS (95% CI) . | P value . | 6-year OS (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .20 | .026 | |||

| 17-60 y | 562 | 52% (48-57) | 65% (61-70) | ||

| >60 y | 229 | 47% (40-54) | 58% (51-65) | ||

| Gender | .91 | .93 | |||

| Male | 450 | 51% (46-56) | 63% (58-68) | ||

| Female | 341 | 51% (41-56) | 64% (58-69) | ||

| Diagnosis | .16 | .69 | |||

| DLBCL NOS | 540 | 51% (46-55) | 63% (59-68) | ||

| HG DH/TH | 32 | 42% (24-61) | 62% (43-81) | ||

| HG NOS | 27 | 39% (18-61) | 52% (30-74) | ||

| PMBL | 55 | 63% (50-77) | 67% (54-81) | ||

| Transformed FL | 76 | 36% (24-49) | 57% (44-69) | ||

| DLBCL gray zone | 18 | 64% (41-87) | 82% (63-100) | ||

| DLBCL T-cell rich | 20 | 63% (38-87) | 61% (25-86) | ||

| Other | 8 | 57% (20-94) | 69% (32-100) | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | .86 | .47 | |||

| I-II | 168 | 50% (42-58) | 61% (53-69) | ||

| III-IV | 774 | 51% (47-56) | 64% (60-68) | ||

| B symptoms | .86 | .40 | |||

| No | 405 | 49% (43-54) | 64% (58-69) | ||

| Yes | 354 | 53% (47-58) | 62% (56-67) | ||

| Bulky disease | .4 | .88 | |||

| No | 504 | 49% (44-54) | 63% (59-68) | ||

| Yes | 241 | 54% (47-60) | 63% (56-69) | ||

| Extranodal involvement | .27 | .88 | |||

| No | 286 | 49% (42-55) | 64% (58-70) | ||

| Yes | 464 | 52% (47-57) | 63% (58-67) | ||

| R-IPI | .15 | .015 | |||

| 0 | 42 | 57% (41-73) | 76% (61-91) | ||

| 1-2 | 329 | 52% (46-58) | 67% (62-73) | ||

| 3-5 | 346 | 48% (43-54) | 58% (53-64) | ||

| Response after first line | .23 | .24 | |||

| CR | 443 | 48% (43-53) | 63% (58-68) | ||

| PR | 154 | 54% (45-62) | 65% (57-73) | ||

| SD | 45 | 63% (49-78) | 73% (59-87) | ||

| PD | 149 | 50% (42-59) | 59% (50-68) | ||

| Characteristics at ASCT | N | 6-year PFS (95% CI) | P value | 6-year OS (95% CI) | P value |

| Age at ASCT | .031 | .001 | |||

| 17-60 y | 501 | 54% (50-59) | 67% (63-72) | ||

| >60 y | 290 | 44% (38-51) | 56% (49-62) | ||

| Disease status at salvage therapy | .22 | .85 | |||

| Late relapse | 314 | 49% (42-55) | 63% (57-69) | ||

| Early relapse | 129 | 46% (37-55) | 62% (53-71) | ||

| Primary refractory | 348 | 54% (49-60) | 64% (58-69) | ||

| Time period | .16 | .020 | |||

| Before 30 October 2012 | 163 | 47% (39-54) | 56% (48-64) | ||

| Beyond 1 November 2012 | 628 | 52% (47-56) | 66% (61-70) | ||

| Second-line therapy | .4 | .5 | |||

| R-ESHAP | 442 | 51% (46-56) | 63% (58-68) | ||

| R-DHAP | 48 | 45% (30-59) | 56% (41-71) | ||

| R-ICE | 41 | 65% (50-81) | 75% (60-89) | ||

| R-GDP | 38 | 32% (0-63) | 61% (25-97) | ||

| Other | 195 | 51% (44-59) | 63% (56-71) | ||

| Conditioning regimen | .63 | .97 | |||

| BEAM | 628 | 51% (47-55) | 64% (60-68) | ||

| R-BEAM | 75 | 45% (32-57) | 61% (49-74) | ||

| Z-BEAM | 19 | 47% (22-67) | 58% (36-80) | ||

| TEAM | 4 | 37% (0-93) | 67% (13-100) | ||

| Other | 49 | 62% (48-76) | 66% (52-79) | ||

| Treatment line at ASCT | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Second line | 617 | 56% (52-60) | 68% (64-72) | ||

| Third line | 147 | 33% (25-41) | 45% (36-54) | ||

| Front line in transformed | 27 | 28% (8-47) | 55% (33-76) | ||

| Pre-ASCT response | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| CR | 481 | 56% (52-61) | 69% (64-73) | ||

| PR | 275 | 43% (37-50) | 57% (50-63) | ||

| SD/PD | 21 | 35% (14-57) | 40% (15-64) |

Boldface values statistical significance.

Multivariate analysis in the overall series

| Variables . | PFS (HR, 95% CI) . | P value . | OS (HR, 95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >60 years at ASCT | 1.31 (1.06-1.62) | .011 | 1.66 (1.30-2.12) | <.001 |

| Time period before 1 November 2012 | --- | --- | 1.40 (1.07-1.83) | .014 |

| Third line vs second line at ASCT | 1.81 (1.42-2.31) | <.001 | 1.90 (1.44-2.5) | <.001 |

| PR vs CR pre-ASCT | 1.46 (1.18-1.81) | <.001 | 1.56 (1.21-1.99) | <.001 |

| SD vs CR pre-ASCT | --- | --- | 3.01 (1.61-5.62) | <.001 |

| Variables . | PFS (HR, 95% CI) . | P value . | OS (HR, 95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >60 years at ASCT | 1.31 (1.06-1.62) | .011 | 1.66 (1.30-2.12) | <.001 |

| Time period before 1 November 2012 | --- | --- | 1.40 (1.07-1.83) | .014 |

| Third line vs second line at ASCT | 1.81 (1.42-2.31) | <.001 | 1.90 (1.44-2.5) | <.001 |

| PR vs CR pre-ASCT | 1.46 (1.18-1.81) | <.001 | 1.56 (1.21-1.99) | <.001 |

| SD vs CR pre-ASCT | --- | --- | 3.01 (1.61-5.62) | <.001 |

Boldface values statistical significance.

Survival according to disease status at ASCT in global series. PFS (A) and OS (B) according to disease status at ASCT in global series.

Survival according to disease status at ASCT in global series. PFS (A) and OS (B) according to disease status at ASCT in global series.

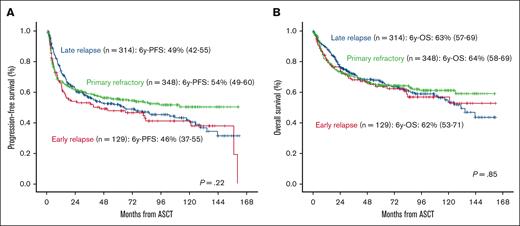

Primary refractory disease or early relapse did not significantly influence survival in the overall series (Figure 3). Analyzing this population separately (n = 477), PFS was influenced by treatment line at ASCT and pre-ASCT response (P < .01, supplemental Table; Figures 3A and 4A). In the multivariate analysis, third line vs second line at ASCT (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.36-2.44; P < .001), front line in transformed vs second line at ASCT (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.03-2.89; P = .04), and PR vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.06-1.79) were only the variables associated with worse PFS. OS was influenced by age at ASCT, treatment line at ASCT, and pre-ASCT response (P < .01, supplemental Table; Figures 3B and 4B). In the multivariate analysis, third line vs second line at ASCT (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.34-2.58; P < .001), front line in transformed vs second line at ASCT (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.35-2.69; P < .001), PR vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.3-2.39; P < .001), and SD vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.33-5.41; P = .006) were the only independent variables for OS.

Survival depending on response to frontline treatment. PFS (A) and OS (B) depending on response to frontline treatment.

Survival depending on response to frontline treatment. PFS (A) and OS (B) depending on response to frontline treatment.

Survival in subgroup of patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse. PFS (A) and OS (B) according to disease status at ASCT in subgroup of patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse.

Survival in subgroup of patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse. PFS (A) and OS (B) according to disease status at ASCT in subgroup of patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse.

Analyzing specifically patients with primary refractory disease (349/791 [40%]), PFS and OS at 6 years were 54% (95% CI, 49-60) and 64% (95% CI, 58-69), respectively. Disease status pre-ASCT in this population was CR in 161 (46%), PR in 167 (48%), SD in 14 (4%), and not evaluated in 7 (2%).

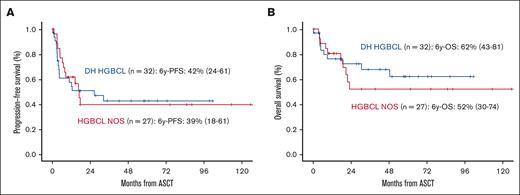

Moreover, 59 patients (7%) were diagnosed with having high-grade BCL, including NOS (27/59) and double-hit/triple-hit (32/59) subtypes. Disease status pre-ASCT in this population was CR in 36 (61%), PR in 19 (32%), and refractory disease in 4 (7%). The percentage of CR cases before ASCT was significantly worse in early relapsing and primary refractory compared with later relapse subgroup (early relapsing cases [8/12, 67%] and primary refractory [11/27, 41%] vs late relapses [17/20, 85%], P = .039). PFS and OS at 6 years were 51% (95% CI, 47-54) and 63% (95% CI, 60-67), respectively (Figure 5A-B).

Survival in patients with high-grade BCL. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients with high-grade BCL (double hit and NOS subtype).

Survival in patients with high-grade BCL. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients with high-grade BCL (double hit and NOS subtype).

NRM and relapse/progression

NRM at 1 year was 9% (95% CI, 7-11) (Figure 1C) and was influenced by age and R-IPI at diagnosis and age at ASCT (P < .001, Table 4). In the multivariate analysis, age >60 years at ASCT (HR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.52-3.42; P < .001) was the only variable associated with higher NRM. CI of relapse at 1 year was 28% (95% CI, 25-31) (Figure 1D) and was influenced by treatment line at ASCT and disease status at ASCT (P < .001, Table 4). In the multivariate analysis, third line vs second line (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.42-2.42; P < .001), PR vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.17-1.88; P < .001), and SD vs CR pre-ASCT (HR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.4-4.57; P = .002) were the only independent variables for CI of relapse. The main causes of death were progression in 161 (58%), ASCT-related toxicity in 18 (6%), and other causes in 98 (35%).

Univariate analysis for NRM and CI of relapse in the overall series

| Characteristics at diagnosis . | N . | 1-year NRM (95% CI) . | P value . | 1-year CI of relapse (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <.001 | .76 | |||

| 17-60 y | 562 | 4% (2-6) | 29% (25-33) | ||

| >60 y | 229 | 9% (5-13) | 25% (19-31) | ||

| Gender | .46 | .72 | |||

| Male | 450 | 5% (3-7) | 28% (23-32) | ||

| Female | 341 | 7% (4-10) | 28% (23-33) | ||

| Diagnosis | .64 | .21 | |||

| DLBCL NOS | 540 | 6% (4-8) | 28% (24-32) | ||

| HGBCL DH/TH | 32 | 10% (0-21) | 34% (17-52) | ||

| HGBCL NOS | 27 | 5% (0-14) | 36% (19-54) | ||

| PMLBCL | 55 | 0% (NA) | 28% (16-40) | ||

| Transformed FL | 76 | 6% (0-11) | 22% (12-31) | ||

| DLBCL gray zone | 18 | 0% (NA) | 36% (13-59) | ||

| DLBCL T-cell rich | 20 | 5% (0-15) | 18% (0-36) | ||

| Other | 8 | 0% (NA) | 14% (0-40) | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | .6 | .99 | |||

| I-II | 168 | 2% (0-5) | 27% (20-33) | ||

| III-IV | 606 | 6% (4-8) | 28% (24-31) | ||

| B-symptoms | .82 | .71 | |||

| No | 405 | 4% (2-6) | 27% (23-32) | ||

| Yes | 354 | 7% (4-10) | 29% (24-34) | ||

| Bulky disease | .41 | .099 | |||

| No | 504 | 6% (4-8) | 29% (25-34) | ||

| Yes | 241 | 4% (2-7) | 26% (20-31) | ||

| Extranodal involvement | .28 | .12 | |||

| No | 286 | 5% (2-7) | 33% (28-39) | ||

| Yes | 464 | 6% (4-8) | 25% (21-29) | ||

| R-IPI | .042 | .47 | |||

| 0 | 42 | 0 (NA) | 20% (8-32) | ||

| 1-2 | 329 | 4% (2-6) | 27% (22-32) | ||

| 3-5 | 346 | 8% (5-10) | 29% (24-34) | ||

| Response after first line | .57 | .42 | |||

| CR | 443 | 5% (3-8) | 26% (22-30) | ||

| PR | 154 | 4% (1-7) | 28% (21-35) | ||

| SD | 45 | 5% (0-12) | 30% (16-44) | ||

| PD | 149 | 8% (3-12) | 33% (25-41) | ||

| Characteristics at ASCT | N | 1-year NRM (95% CI) | P value | 1-year CI of relapse (95% CI) | P value |

| Age | <.001 | .92 | |||

| 17-60 y | 501 | 4% (2-5) | 30% (26-34) | ||

| >60 y | 290 | 9% (6-13) | 25% (19-30) | ||

| Disease status at salvage therapy | .35 | .17 | |||

| Late relapse | 314 | 6% (3-9) | 24% (19-28) | ||

| Early relapse | 129 | 4% (0-8) | 32% (24-41) | ||

| Primary refractory | 348 | 6% (3-8) | 30% (25-35) | ||

| Time period | .31 | .22 | |||

| Before 30 October 2012 | 628 | 6% (4-8) | 27% (23-30) | ||

| Beyond 1 November 2012 | 163 | 6% (2-9) | 31% (24-39) | ||

| Second-line therapy | .45 | .74 | |||

| R-ESHAP | 442 | 6% (4-8) | 28% (24-32) | ||

| R-DHAP | 48 | 11% (2-20) | 35% (20-49) | ||

| R-ICE | 41 | 0% (NA) | 28% (14-42) | ||

| R-GDP | 38 | 0% (NA) | 14% (3-26) | ||

| Other | 195 | 6% (3-10) | 29% (22-36) | ||

| Conditioning regimen | .86 | .23 | |||

| BEAM | 628 | 5% (3-7) | 27% (24-31) | ||

| R-BEAM | 75 | 6% (0-11) | 30% (19-41) | ||

| Z-BEAM | 19 | 13% (0-29) | 50% (27-73) | ||

| TEAM | 4 | 100% (NA) | 25% (0-67) | ||

| Other | 49 | 9% (0-17) | 21% (10-33) | ||

| Treatment line at ASCT | .10 | <.001 | |||

| Second line | 617 | 5% (3-7) | 24% (20-27) | ||

| Third line | 147 | 8% (3-12) | 46% (38-55) | ||

| Front line in transformed | 27 | 4% (0-11) | 20% (4-35) |

| Characteristics at diagnosis . | N . | 1-year NRM (95% CI) . | P value . | 1-year CI of relapse (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <.001 | .76 | |||

| 17-60 y | 562 | 4% (2-6) | 29% (25-33) | ||

| >60 y | 229 | 9% (5-13) | 25% (19-31) | ||

| Gender | .46 | .72 | |||

| Male | 450 | 5% (3-7) | 28% (23-32) | ||

| Female | 341 | 7% (4-10) | 28% (23-33) | ||

| Diagnosis | .64 | .21 | |||

| DLBCL NOS | 540 | 6% (4-8) | 28% (24-32) | ||

| HGBCL DH/TH | 32 | 10% (0-21) | 34% (17-52) | ||

| HGBCL NOS | 27 | 5% (0-14) | 36% (19-54) | ||

| PMLBCL | 55 | 0% (NA) | 28% (16-40) | ||

| Transformed FL | 76 | 6% (0-11) | 22% (12-31) | ||

| DLBCL gray zone | 18 | 0% (NA) | 36% (13-59) | ||

| DLBCL T-cell rich | 20 | 5% (0-15) | 18% (0-36) | ||

| Other | 8 | 0% (NA) | 14% (0-40) | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | .6 | .99 | |||

| I-II | 168 | 2% (0-5) | 27% (20-33) | ||

| III-IV | 606 | 6% (4-8) | 28% (24-31) | ||

| B-symptoms | .82 | .71 | |||

| No | 405 | 4% (2-6) | 27% (23-32) | ||

| Yes | 354 | 7% (4-10) | 29% (24-34) | ||

| Bulky disease | .41 | .099 | |||

| No | 504 | 6% (4-8) | 29% (25-34) | ||

| Yes | 241 | 4% (2-7) | 26% (20-31) | ||

| Extranodal involvement | .28 | .12 | |||

| No | 286 | 5% (2-7) | 33% (28-39) | ||

| Yes | 464 | 6% (4-8) | 25% (21-29) | ||

| R-IPI | .042 | .47 | |||

| 0 | 42 | 0 (NA) | 20% (8-32) | ||

| 1-2 | 329 | 4% (2-6) | 27% (22-32) | ||

| 3-5 | 346 | 8% (5-10) | 29% (24-34) | ||

| Response after first line | .57 | .42 | |||

| CR | 443 | 5% (3-8) | 26% (22-30) | ||

| PR | 154 | 4% (1-7) | 28% (21-35) | ||

| SD | 45 | 5% (0-12) | 30% (16-44) | ||

| PD | 149 | 8% (3-12) | 33% (25-41) | ||

| Characteristics at ASCT | N | 1-year NRM (95% CI) | P value | 1-year CI of relapse (95% CI) | P value |

| Age | <.001 | .92 | |||

| 17-60 y | 501 | 4% (2-5) | 30% (26-34) | ||

| >60 y | 290 | 9% (6-13) | 25% (19-30) | ||

| Disease status at salvage therapy | .35 | .17 | |||

| Late relapse | 314 | 6% (3-9) | 24% (19-28) | ||

| Early relapse | 129 | 4% (0-8) | 32% (24-41) | ||

| Primary refractory | 348 | 6% (3-8) | 30% (25-35) | ||

| Time period | .31 | .22 | |||

| Before 30 October 2012 | 628 | 6% (4-8) | 27% (23-30) | ||

| Beyond 1 November 2012 | 163 | 6% (2-9) | 31% (24-39) | ||

| Second-line therapy | .45 | .74 | |||

| R-ESHAP | 442 | 6% (4-8) | 28% (24-32) | ||

| R-DHAP | 48 | 11% (2-20) | 35% (20-49) | ||

| R-ICE | 41 | 0% (NA) | 28% (14-42) | ||

| R-GDP | 38 | 0% (NA) | 14% (3-26) | ||

| Other | 195 | 6% (3-10) | 29% (22-36) | ||

| Conditioning regimen | .86 | .23 | |||

| BEAM | 628 | 5% (3-7) | 27% (24-31) | ||

| R-BEAM | 75 | 6% (0-11) | 30% (19-41) | ||

| Z-BEAM | 19 | 13% (0-29) | 50% (27-73) | ||

| TEAM | 4 | 100% (NA) | 25% (0-67) | ||

| Other | 49 | 9% (0-17) | 21% (10-33) | ||

| Treatment line at ASCT | .10 | <.001 | |||

| Second line | 617 | 5% (3-7) | 24% (20-27) | ||

| Third line | 147 | 8% (3-12) | 46% (38-55) | ||

| Front line in transformed | 27 | 4% (0-11) | 20% (4-35) |

HGBCL, high-grade BCL.

Boldface values statistical significance.

Subsequent cellular therapies

From 307 patients who relapsed after ASCT (39%), 59 received CAR-T therapy (19%) with a 1-year OS of 79% (95% CI, 69-90) and 1-year NRM of 8% (95% CI, 0-15). In addition, 68 patients received allo-SCT (22%) with 1-year OS of 50% (95% CI, 38-62) and 1-year NRM of 38% (95% CI, 26-51). Median follow-up for patients who received CAR-T therapy and allo-SCT was 25 months (95% CI, 22-27) and 82 months (95% CI, 49-115), respectively.

Discussion

HDT followed by ASCT has historically been the treatment of choice for transplant-eligible patients with R/R LBCL and chemosensitive disease. To our knowledge, this is the largest series analyzing the efficacy of ASCT in patients with R/R LBCL after rituximab-containing frontline therapy. Our results confirm a 6-year-PFS and OS of 51% (95% CI, 47-54) and 63% (95% CI, 60-67), respectively, with NRM at 1 year of 9% (95% CI, 7-11). If we focused on the impact of the time periods on survival, better OS was confirmed for patients transplanted after 1 November 2012. This finding is probably related to better management of toxicity because of the improvements in supportive care.

Regarding second-line regimen, CORAL trial analyzed 396 patients who were randomized to receive rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide or rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine and cisplatin, whereas NCIC-CTG LY.12 trial included 619 patients who were assigned to gemcitabine, cisplatin and dexamethasone or dexamethasone, cytarabine and cisplatin, and in none of them significant differences were observed between the different regimens in terms of response rates, PFS, and OS.4,12 The ORCHARRD trial, replacing rituximab with ofatumumab, was not associated with a higher benefit.5 Other regimens frequently used in Spain, such as rituximab, etoposide, cytarabine, cisplatin and methylprednisolone, have been evaluated in retrospective studies with similar efficacy.13 In our series, 56% of the patients received rituximab, etoposide, cytarabine, cisplatin and methylprednisolone as a second-line treatment and no differences in survival were observed compared with other schemes.

The timing of progression or relapse is the most important prognostic factor in the context of second line with durable remission rates ∼50% for patients with late relapse (>1 year from diagnosis or from the end of first line) but <20% for patients with refractory or early relapse.4,6 SCHOLAR-1 retrospective study defined a refractory population that included patients who progressed or did not respond to first line, salvage treatment, or those who reached ASCT but relapsed in <12 months from the end of the first-line therapy. These patients had a CR rate <10% to the next line of treatment with a median OS of ∼6 months.14 However, several studies have revealed that despite early failure of first line, patients with chemosensitive disease after salvage therapy can be still cured with ASCT consolidation15,16,1 and those patients with primary refractory disease who respond to second line,17 as we also confirm in our study. We separately analyzed patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse confirming similar survival than the overall series. Therefore, outside clinical trials, ASCT could be an option in chemosensitive relapses regardless of the period of time until treatment failure in centers without availability for CAR-T therapy.

Recently, CAR-T therapy (axicabtagene ciloleucel [axi-cel] and lisocabtagene maraleucel [liso-cel]) has been approved in second line for patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse, after demonstrating significantly better EFS compared with salvage treatment followed by HDT/ASCT,7-9 and nowadays, it is considered the treatment of choice in second line for these subpopulations. However, patients with late relapse should still be considered for ASCT in the absence of robust data demonstrating CAR-T superiority in this subgroup. Furthermore, there are still centers with limited access to this therapy, and, based on our results and according to ASTCT Clinical Practice Recommendations,18 ASCT could still be considered an acceptable consolidation therapy in eligible patients. Shadman et al recently reported a lower CI of relapse and a superior survival (higher PFS for patients with CR and higher OS for patients with PR) with ASCT compared with CAR-T therapy for the subgroup of patients with early treatment failure who achieved PR or CR after salvage therapy.19,20 However, it should be noted that this was a retrospective analysis and patients treated with CAR-T therapy had significantly more lines of previous therapy compared with patients with ASCT. In addition, it is worth highlighting that studies focused on transplantation, including ours, include series of highly selected patients, with relapsed or refractory disease but with maintained chemosensitivity during several cycles of chemotherapy, which allows them to undergo ASCT.

Concerning disease status pretransplant measured by positron emission tomography (PET), several studies confirmed that positive PET result pre-ASCT predicts worse survival.21,22 In a recent study including 249 patients with PET-positive PR pre-ASCT, patients were divided into 2 cohorts, early failure (primary refractory patients and relapses <12 months) and late treatment failure (relapses >12 months).23 No significant differences between both groups were observed in terms of PFS, although a higher mortality rate was observed in the earlier treatment failure group. In our study, no differences were observed either between early and late treatment failure in terms of survival nor neither in NRM in patients with PET-positive PR pre-ASCT (Table 2; supplemental Table). Furthermore, 35% of the patients had PR pretransplant, and we confirmed worse PFS and OS in this subgroup compared with the subgroup of patients with CR.

In our study, patients with high-grade BCL, including double-hit lymphomas, had favorable long-term survival outcomes (6 year PFS and OS of 51% and 63%, respectively), which contrasts with previously published results by Herrera et al (4-year PFS and OS of 28% and 25%, respectively, for patients with double-hit lymphoma).24 However, in the results reported by Herrera et al, there were a higher proportion of PR pre-ASCT than in our series (75% vs 32%) and a lower proportion of CR (25% vs 61%), which could explain in part our better results. In addition, the patients included in the study of Herrera et al24 underwent ASCT between 2000 and 2013 and in our study from 2010 to 2021, which could probably lead to higher OS related to better management of toxicity because of the improvements in supportive care. Furthermore, we now know that the group considered double-hit lymphoma in the 2016 World Health Organization classification is a biologically heterogeneous group and includes patients with different prognoses, so new analyses would be necessary considering the entities included in the new classifications.25,26

One limitation of our study is that the disease status was assessed by the local team of each center, and in some of them, pre-ASCT response was probably assessed by computer tomography scan instead of PET. Therefore, some PR could be CR by PET.

Another limitation of our study, as previously mentioned, is that this is a registry study focused on ASCT, so we have analyzed highly selected patients with chemosensitive disease who managed to consolidate with the ASCT. Several studies indicate that only ∼40% of the patients with R/R LBCL finally received ASCT because of the refractoriness of the disease,4-6 so our study does not reflect the overall prognosis of patients with R/R LBCL. Other limitations of our study include the lack of centralized pathology confirmation across centers and the lack on data regarding the incidence of secondary primary malignancies or toxicities, such as mucositis, infections, or cytopenias.

To conclude, our results indicate that ASCT is a curative option for patients with chemosensitive disease (especially in CR after salvage), regardless of the timing of relapse after frontline treatment. These data support that ASCT could still be considered in patients with primary refractory or early relapse in centers with limited access to CAR-T therapy, provided the disease is sensitive to salvage therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Grupo Español de Trasplante y Terapia Celular and Grupo Español de Linfoma y Trasplante Autólogo for their support, especially Ángel Cedillo and Silvia Filaferro for their contribution in obtaining the clinical data of the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: L.B. and A.M.G.-S. conducted the research; L.B., A.G., C.M., M.C.O.V., M.S., A.C.C., M. Peña, A.P., A.J.-U., M.B.-O., P.F.C.-G., B.N., I.S., P.A., I.E., J.C., F.M.-M., L. García, P. Gómez, M.R.V., M. Puente, J.Z., T.Z., I.Z., R.d.C., L. González, P. González, C.B., J.R., M.S., M.F.-S., A.C., A.M., J.M., A. Sampol, A. Sureda, D.C., and A.M.G.-S. contributed to clinical data; L.B., A.G., A. Sureda, and A.M.G.-S. contributed to the analysis and data interpretation; A.G. performed the statistical analysis; and all authors contributed to review and provided their comments on this manuscript and approval of the final version.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the Grupo Español de Trasplante y Terapia Celular and Grupo Español de Linfoma y Trasplante Autólogo appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Leyre Bento, Hematology Department, Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Ctra Valldemossa, 79 1º Floor I Module, 07120 Palma, Spain; email: leyre.bento@ssib.es.

Appendix

The members of the Grupo Español de Trasplante y Terapia Celular are Leyre Bento, Carmen Martínez, Marta Peña, Ariadna Pérez, Mariana Bastos-Oreiro, Paula Fernández Caldas-González, Ignacio Español, Javier Cornago, María Rosario Varela, Joud Zanabili, Teresa Zudaire, Izaskun Zeberio, Leslie González, Pedro González, Cristina Blázquez, Alberto Mussetti, Juan Montoro, Antonia Sampol, Anna Sureda, and Dolores Caballero.

The members of the Grupo Español de Linfoma y Trasplante Autólogo are Leyre Bento, Antonio Gutiérrez, Carmen Martínez, Marta Peña, Ana Jiménez-Ubieto, Mariana Bastos-Oreiro, Paula Fernández Caldas-González, Belén Navarro, Pau Abrisqueta, Fernando Martín-Moro, Pilar Gómez, Izaskun Zeberio, Raquel del Campo, Jordina Rovira, Mireia Franch-Sarto, Almudena Cabero, Anna Sureda, Dolores Caballero, and Alejandro Martín García-Sancho.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Leyre Bento (leyre.bento@ssib.es).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.