Key Points

NGS-MRD monitoring from PB after alloHCT detects up to 38% and 64% of relapses with a monitoring interval of every 3 or 1 months.

Known mutations from diagnosis, including DTA mutations, show the longest lead time to relapse after alloHCT and are useful for MRD monitoring.

Visual Abstract

Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who experience relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) face unfavorable outcomes regardless of the chosen relapse treatment. Early detection of relapse at the molecular level by measurable residual disease (MRD) assessment enables timely intervention, which may prevent hematological recurrence of the disease. It remains unclear whether molecular MRD assessment can detect MRD before impending relapse and, if so, how long in advance. This study elucidates the molecular architecture and kinetics preceding AML relapse by using error-corrected next-generation sequencing (NGS) in 74 patients with AML relapsing after alloHCT, evaluating 140 samples from peripheral blood collected 0.6 to 14 months before relapse. At least 1 MRD marker became detectable in 10%, 38%, and 64% of patients at 6, 3, and 1 month before relapse, respectively. By translating these proportions into monitoring intervals, 38% of relapses would have been detected through MRD monitoring every 3 months, whereas 64% of relapses would have been detected with monthly intervals. The relapse kinetics after alloHCT are influenced by the functional class of mutations and their stability during molecular progression. Notably, mutations in epigenetic modifier genes exhibited a higher prevalence of MRD positivity and greater stability before relapse, whereas mutations in signaling genes demonstrated a shorter lead time to relapse. Both DTA (DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1) and non-DTA mutations displayed similar relapse kinetics during the follow-up period after alloHCT. Our study sets a framework for MRD monitoring after alloHCT by NGS, supporting monthly monitoring from peripheral blood using all variants that are known from diagnosis.

Introduction

The relapse incidence after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can be as high as 50%, depending on patient, disease, and treatment factors,1,2 with dismal outcomes and a median overall survival (OS) of a few months irrespective of the relapse treatment.3 Even younger adult patients with AML aged <50 years face a considerable risk of death from relapse after alloHCT, as evidenced by a 2-year OS rate of relapsing patients of only 26%.4

The detection of residual leukemia cells in remission, referred to as measurable residual disease (MRD), can serve as a trigger for preemptive therapies, as initiating treatment at MRD relapse with low disease burden may yield better outcomes and improved tolerability compared with treatment at hematological relapse.5,6 Treatment options for MRD relapses are limited and can be categorized into strategies that enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect, such as donor lymphocyte infusions or tapering of immunosuppression,7-9 or reintroduction of chemotherapy (such as intensive chemotherapy, Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3 [FLT3]-targeted therapies, or azacitidine/venetoclax-based salvage regimens).10-12 In a subset of patients, a second alloHCT may offer a potential cure.13 Because patients who experience MRD relapse have inferior outcomes and a higher risk of relapse,14,15 the international working group for MRD assessment and validation in AML, ELN-DAVID (the European LeukemiaNet International Working Group for MRD Assessment and Validation in AML), recommends molecular MRD monitoring for routine follow-up after alloHCT.16

Currently, there is no standard method for AML-MRD testing after alloHCT. An ideal technique for MRD monitoring should possess high sensitivity to detect residual cells at low levels and be reproducible, rapid, and applicable to a broad range of patients. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) shows promise as a sensitive and well-standardizable approach.17-19 Previous studies using NGS for MRD detection have demonstrated a correlation between MRD positivity pre-alloHCT and post-alloHCT and a higher cumulative incidence of relapse (MRD pre-alloHCT with a 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse [CIR] of 66% in MRD-positive vs 17% in MRD-negative patients, and MRD post-alloHCT with a 5-year CIR of 53% in MRD-positive vs 26% in MRD-negative patients).14,20

Although it is agreed on that MRD-positive patients after alloHCT face a higher risk of relapse, it remains unclear whether, and by how long in advance, NGS assessment can detect MRD before impending hematological relapse, as well as which molecular markers are clinically valuable for this purpose. Here, we aimed to investigate (1) clonal dynamics before relapse onset post-alloHCT, (2) MRD kinetics of mutations known from diagnosis (stable mutations) compared with mutations emerging at relapse (gained mutations), and (3) the potential of markers of clonal hematopoiesis, such as DTA (DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1) mutations, as reliable indicators for MRD relapse during follow-up after alloHCT from peripheral blood, enabling early detection of hematological relapse in patients with AML.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients were eligible for retrospective relapse monitoring from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB-MNCs) if they were aged ≥18 years, had a diagnosis of AML excluding acute promyelocytic leukemia, and underwent alloHCT with pretransplant remission status of first or second complete remission (CR), CR with incomplete hematologic recovery, or non-CR between 2000 and 2020 at Hannover Medical School. All patients had to be diagnosed with hematological relapse ≥14 days after alloHCT, which was defined as a blast increase of ≥5% in peripheral blood or bone marrow. Twenty-one patients with isolated extramedullary recurrence were initially excluded, as MRD monitoring in peripheral blood or bone marrow for extramedullary relapse is not established. The selection criteria of patients and samples is shown in a consort diagram in supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood website) and explained in supplemental Methods. Cytogenetic and molecular characteristics at diagnosis and relapse of patients in whom no mutation was detected at relapse (n = 13) are shown in supplemental Table 1.

Clinical data were collected from an electronic database at Hannover Medical School. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Hannover Medical School (ethical votes 936-2011 and 3432-2016) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Molecular analysis, error-corrected sequencing for sensitive MRD detection, and cytogenetic analysis

For the myloid panel sequencing and amplicon-based NGS, DNA was extracted using the Allprep DNA/RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Analysis of relapse and diagnosis samples with a custom TruSight myeloid sequencing panel covering 46 AML-related entire genes or hot spots was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA) (supplemental Table 2).

Bioinformatics analysis of myeloid panel and amplicon-based error-corrected sequencing was performed as previously described and summarized in supplemental Methods.20 G- and R-banding analysis identified chromosomal aberrations at the time of diagnosis and relapse and were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (2016).21

Bioinformatics and statistical analyses

Labeling of a variant as MRD positive or negative followed the previously described standardized algorithm that differentiates between single-nucleotide variants and small and large insertions/deletions based on the number of read families (read family mode, error-corrected sequencing) or the number of matching forward and reverse reads (forward/reverse mode) to define the limit of detection.20 Criteria for defining the limit of detection and MRD positivity are described in the supplemental Methods.

If multiple gene mutations per patient were used for MRD monitoring, the patient was defined as MRD positive when at least 1 of the mutations at 1 time point before relapse was called MRD positive. To assess clonal relapse dynamics, prerelapse samples were assigned to the monthly interval before relapse that best matched the sampling time. MRD status of each marker or each patient was assumed negative until the first sample was measured positive. MRD positivity was assumed for all following time intervals until relapse. By calculating the number of positive patients (mutations) in a given interval as a fraction of the total number of patients (mutations), we were able to compare relapse kinetic patterns for patients and mutations, respectively. For data visualization, these fractions were then plotted against time to relapse and the functions were approximated by the fifth-order polynomial function .22,23 Myeloid panel sequencing of additional samples at the time of AML diagnosis was performed for 59 of 74 patients. If a relapse mutation was detectable in the diagnostic sample, it was considered “stable.” However, if a mutation was detected only at the time of diagnosis but not at the time of relapse, it was considered to be “lost” or, vice versa, “gained” during the course of the disease.

Comparisons of variables were performed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the χ2 test for categorical variables for exploratory purposes with a 2-sided level of significance set at P < .05. The statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY), GraphPad Prism, version 9.3.1, statistical program R24 using packages “survival” and “survminer,” and Microsoft Excel 2019, version 16.64 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

For statistical analyses of clinical outcomes, remission duration end points were measured from the date of alloHCT to documented relapse or from relapse to death or last follow-up if the patient was alive. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the distribution of CIR and OS, and differences between the survival of 2 groups were analyzed using the 2-sided log-rank test.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Hannover Medical School (ethical votes 936-2011 and 3432-2016).

Results

Patient characteristics

To characterize the relapse kinetics after alloHCT, 200 patients with posttransplant relapse were evaluated for inclusion. Seventy-four of them had a relapse sample with recurrent genetic aberrations and ≥1 prerelapse samples available and were included in our study (supplemental Figure 1).

Median age was 52 years at diagnosis (Table 1). Twenty-one (28%) patients had secondary AML, and 27 (36%) were classified as 2022 ELN adverse risk. Twenty-one (28%) patients underwent alloHCT with active disease, 13 (18%) received mismatched grafts, and 30 (41%) were conditioned with reduced intensity (Table 1). Information on tapering immunosuppressive therapy is provided in supplemental Table 3.

Clinical and transplantation-associated characteristics at diagnosis in patients with and without detectable MRD before relapse (full cohort of 74 patients, mutations in DTA and non-DTA genes were used as MRD markers)

| Characteristic . | All patients (n = 74) . | Molecular marker positive (n = 47, 64%) . | Molecular marker negative (n = 27, 36%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .727 | |||

| Median | 51.9 | 53.2 | 49.6 | |

| Range | 18.2-71.7 | 20.2-71.7 | 18.2-66.8 | |

| Patient sex, no. (%) | .153 | |||

| Male | 41 (55) | 29 (62) | 12 (44) | |

| Female | 33 (45) | 18 (38) | 15 (56) | |

| ECOG performance status before alloHCT, no. (%) | .280 | |||

| ECOG 0-1 | 72 (97) | 45 (96) | 27 (100) | |

| ECOG ≥2 | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| FAB subtype, no. (%) | .061 | |||

| M0 | 7 (9) | 7 (15) | 0 (0) | |

| M1 + M2 | 22 (30) | 16 (34) | 6 (22) | |

| M4 + M5 | 28 (38) | 14 (30) | 14 (52) | |

| M6 + M7 | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | |

| Not classifiable | 15 (20) | 10 (21) | 5 (19) | |

| AML type, no. (%) | .377 | |||

| De novo | 53 (72) | 32 (68) | 21 (78) | |

| Secondary∗ | 21 (28) | 15 (32) | 6 (22) | |

| 2022 ELN risk group, no. (%) | .668 | |||

| Favorable | 5 (7) | 3 (6) | 2 (7) | |

| Intermediate | 42 (57) | 26 (55) | 16 (59) | |

| Adverse | 27 (36) | 18 (38) | 9 (33) | |

| Cytogenetic risk group, no. (%)† | .457 | |||

| Favorable | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Intermediate | 49 (66) | 32 (68) | 17 (63) | |

| Adverse | 24 (32) | 14 (30) | 10 (37) | |

| Complex karyotype, no. (%) | .423 | |||

| Absent | 56 (76) | 37 (79) | 19 (70) | |

| Present | 18 (24) | 10 (21) | 8 (30) | |

| WBC count, ×109/L | .675 | |||

| Median | 15.9 | 12 | 21.8 | |

| Range | 0.5-280.6 | 0.5-259.4 | 2.1-280.6 | |

| No information, no. (%) | 23 (31) | 12 (26) | 11 (41) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .216 | |||

| Median | 9 | 9 | 8 | |

| Range | 5-15 | 5-15 | 5-13 | |

| No information, no. (%) | 21 (28) | 11 (23) | 10 (37) | |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | .647 | |||

| Median | 58 | 58 | 60 | |

| Range | 7-475 | 7-475 | 20-189 | |

| No information, no. (%) | 21 (28) | 11 (23) | 10 (37) | |

| HCT-CI score before transplantation, no. (%) | .698 | |||

| 0-2 | 46 (62) | 30 (64) | 16 (59) | |

| >2 | 28 (38) | 17 (36) | 11 (41) | |

| Remission status before alloHCT, no. (%) | .908 | |||

| First CR | 44 (59) | 27 (57) | 17 (63) | |

| CRi | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| Second CR | 8 (11) | 8 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| No CR | 21 (28) | 12 (26) | 9 (33) | |

| Donor match, no. (%) | .733 | |||

| MRDonor | 22 (30) | 12 (26) | 10 (37) | |

| MUDonor | 39 (53) | 28 (60) | 11 (41) | |

| MMRDonor/MMUDonor | 13 (18) | 7 (15) | 6 (22) | |

| Conditioning therapy, no. (%) | .316 | |||

| Myeloablative | 44 (59) | 30 (64) | 14 (52) | |

| Reduced intensity | 30 (41) | 17 (36) | 13 (48) | |

| Stem cell source, no. (%) | .081 | |||

| Peripheral blood | 5 (7) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Bone marrow | 69 (93) | 42 (89) | 27 (100) | |

| Donor sex, no. (%) | .951 | |||

| Male | 49 (66) | 31 (66) | 18 (67) | |

| Female | 25 (34) | 16 (34) | 9 (33) | |

| CMV status, no. (%) | .925 | |||

| Donor neg/patient neg | 16 (22) | 10 (21) | 6 (22) | |

| Any other constellation | 58 (78) | 37 (79) | 21 (78) | |

| Second malignancy, no. (%) | .108 | |||

| Yes | 8 (11) | 3 (6) | 5 (19) | |

| No | 66 (89) | 44 (94) | 22 (81) | |

| Extramedullary disease, no. (%) | .899 | |||

| Pretransplant | 56 (76) | 36 (77) | 20 (74) | |

| Posttransplant | 6 (8) | 2 (4) | 4 (15) | |

| Pretransplant and posttransplant | 5 (7) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Never | 7 (9) | 4 (9) | 3 (11) |

| Characteristic . | All patients (n = 74) . | Molecular marker positive (n = 47, 64%) . | Molecular marker negative (n = 27, 36%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .727 | |||

| Median | 51.9 | 53.2 | 49.6 | |

| Range | 18.2-71.7 | 20.2-71.7 | 18.2-66.8 | |

| Patient sex, no. (%) | .153 | |||

| Male | 41 (55) | 29 (62) | 12 (44) | |

| Female | 33 (45) | 18 (38) | 15 (56) | |

| ECOG performance status before alloHCT, no. (%) | .280 | |||

| ECOG 0-1 | 72 (97) | 45 (96) | 27 (100) | |

| ECOG ≥2 | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| FAB subtype, no. (%) | .061 | |||

| M0 | 7 (9) | 7 (15) | 0 (0) | |

| M1 + M2 | 22 (30) | 16 (34) | 6 (22) | |

| M4 + M5 | 28 (38) | 14 (30) | 14 (52) | |

| M6 + M7 | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | |

| Not classifiable | 15 (20) | 10 (21) | 5 (19) | |

| AML type, no. (%) | .377 | |||

| De novo | 53 (72) | 32 (68) | 21 (78) | |

| Secondary∗ | 21 (28) | 15 (32) | 6 (22) | |

| 2022 ELN risk group, no. (%) | .668 | |||

| Favorable | 5 (7) | 3 (6) | 2 (7) | |

| Intermediate | 42 (57) | 26 (55) | 16 (59) | |

| Adverse | 27 (36) | 18 (38) | 9 (33) | |

| Cytogenetic risk group, no. (%)† | .457 | |||

| Favorable | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Intermediate | 49 (66) | 32 (68) | 17 (63) | |

| Adverse | 24 (32) | 14 (30) | 10 (37) | |

| Complex karyotype, no. (%) | .423 | |||

| Absent | 56 (76) | 37 (79) | 19 (70) | |

| Present | 18 (24) | 10 (21) | 8 (30) | |

| WBC count, ×109/L | .675 | |||

| Median | 15.9 | 12 | 21.8 | |

| Range | 0.5-280.6 | 0.5-259.4 | 2.1-280.6 | |

| No information, no. (%) | 23 (31) | 12 (26) | 11 (41) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .216 | |||

| Median | 9 | 9 | 8 | |

| Range | 5-15 | 5-15 | 5-13 | |

| No information, no. (%) | 21 (28) | 11 (23) | 10 (37) | |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | .647 | |||

| Median | 58 | 58 | 60 | |

| Range | 7-475 | 7-475 | 20-189 | |

| No information, no. (%) | 21 (28) | 11 (23) | 10 (37) | |

| HCT-CI score before transplantation, no. (%) | .698 | |||

| 0-2 | 46 (62) | 30 (64) | 16 (59) | |

| >2 | 28 (38) | 17 (36) | 11 (41) | |

| Remission status before alloHCT, no. (%) | .908 | |||

| First CR | 44 (59) | 27 (57) | 17 (63) | |

| CRi | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| Second CR | 8 (11) | 8 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| No CR | 21 (28) | 12 (26) | 9 (33) | |

| Donor match, no. (%) | .733 | |||

| MRDonor | 22 (30) | 12 (26) | 10 (37) | |

| MUDonor | 39 (53) | 28 (60) | 11 (41) | |

| MMRDonor/MMUDonor | 13 (18) | 7 (15) | 6 (22) | |

| Conditioning therapy, no. (%) | .316 | |||

| Myeloablative | 44 (59) | 30 (64) | 14 (52) | |

| Reduced intensity | 30 (41) | 17 (36) | 13 (48) | |

| Stem cell source, no. (%) | .081 | |||

| Peripheral blood | 5 (7) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Bone marrow | 69 (93) | 42 (89) | 27 (100) | |

| Donor sex, no. (%) | .951 | |||

| Male | 49 (66) | 31 (66) | 18 (67) | |

| Female | 25 (34) | 16 (34) | 9 (33) | |

| CMV status, no. (%) | .925 | |||

| Donor neg/patient neg | 16 (22) | 10 (21) | 6 (22) | |

| Any other constellation | 58 (78) | 37 (79) | 21 (78) | |

| Second malignancy, no. (%) | .108 | |||

| Yes | 8 (11) | 3 (6) | 5 (19) | |

| No | 66 (89) | 44 (94) | 22 (81) | |

| Extramedullary disease, no. (%) | .899 | |||

| Pretransplant | 56 (76) | 36 (77) | 20 (74) | |

| Posttransplant | 6 (8) | 2 (4) | 4 (15) | |

| Pretransplant and posttransplant | 5 (7) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Never | 7 (9) | 4 (9) | 3 (11) |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; CRi, CR with incomplete hematologic recovery; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; FAB, French American British Classification; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation–comorbidity index; MMRDonor, mismatched related donor; MMUDonor, mismatched unrelated donor; MRDonor, matched related donor; MUDonor, matched unrelated donor; neg, negative; WBC, white blood cell.

AML secondary to myelodysplastic syndrome or therapy-related AML

Cytogenetic risk group is defined according to Medical Research Council criteria.22

Molecular characteristics at diagnosis and relapse

At relapse, the most frequently mutated genes used for retrospective MRD analysis were FLT3 (FLT3-ITD [internal tandem duplication], n = 28; FLT3-TKD [tyrosine-kinase domain], n = 1), DNMT3A (n = 29), TP53 (n = 20), NPM1 (n = 15), and WT1 (n = 14) (supplemental Figure 2). A diagnostic sample was available for 59 (80%) patients. In this subgroup, 211 mutations were identified at diagnosis (n = 162) and/or relapse (n = 180). The majority (n = 132, 63%) of all 211 mutations were present both at diagnosis and relapse and were defined as stable mutations. Looking at the evolution of mutations from the time point of diagnosis, 81% (132 of 162) of all mutations present at diagnosis later reappeared at relapse. Looking at the evolution of mutations from the time point of relapse (backwards), 73% (132 of 180) of all mutations present at relapse had been present at diagnosis.

The most frequent mutations stable between diagnosis and relapse belonged to spliceosome (11 of 14, 79%) and epigenetic modifier genes (38 of 53, 72%), whereas mutations in signal transduction genes were less stable (30 of 68, 44%) (supplemental Figure 3). The number of mutations at diagnosis had no impact on OS measured from the day of alloHCT (supplemental Figure 4).

MRD monitoring before relapse

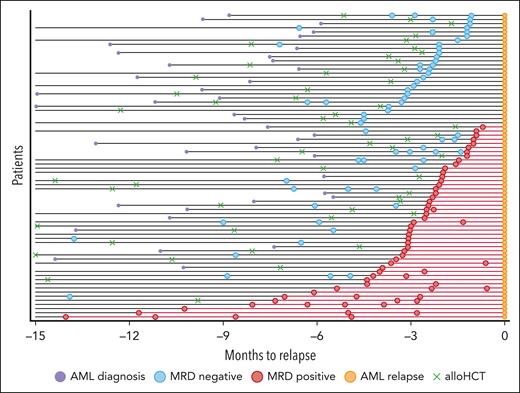

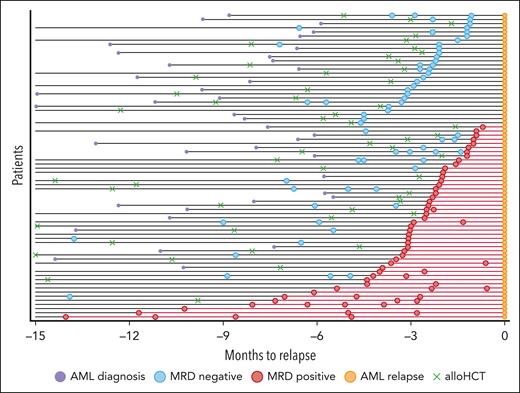

A total of 140 prerelapse samples were available from all 74 patients (range, 1-5 samples per patient). More than 80% of these samples were collected at 6 months or less before hematological relapse (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 5). The median time to relapse of these samples was 3.1 months (range, 0.6-14 months) (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 6). A total of 213 mutations in 39 different genes were used for MRD monitoring (median, 3 per patient; range, 1-7). Each mutation was analyzed in 1 to 6 samples (296 measurements in total).

Overview of patient samples and disease course. x axis: time before relapse, which is designated time t = 0. y axis: number of relapsed patients with AML. Orange circles: time of hematological relapse; green crosses: time of alloHCT; blue circles: MRD-negative samples; red circles: MRD-positive samples; purple circles: time of AML diagnosis; black lines: time from AML diagnosis to relapse; red lines connect positive samples and mark the time interval when patients are considered MRD positive.

Overview of patient samples and disease course. x axis: time before relapse, which is designated time t = 0. y axis: number of relapsed patients with AML. Orange circles: time of hematological relapse; green crosses: time of alloHCT; blue circles: MRD-negative samples; red circles: MRD-positive samples; purple circles: time of AML diagnosis; black lines: time from AML diagnosis to relapse; red lines connect positive samples and mark the time interval when patients are considered MRD positive.

Of 213 known mutations, 100 (47%) could be detected in the prerelapse samples. The median variant allele frequency (VAF) of detectable variants was 0.132% (range, 0.0048%-26%), and the median limit of detection across all targets was 0.0148% (range, 0.0018%-0.477%) and was slightly different for each gene (supplemental Table 4). Patients with at least 1 detectable mutation in at least 1 prerelapse sample were considered MRD positive. This resulted in 47 (64%) MRD-positive patients. In 25 patients (34%), all variants were positive in at least 1 prerelapse sample. The remaining 27 (36%) patients were classified as MRD negative. The median time from closest MRD sample to clinical relapse was 2.4 months (range, 0.6-10.23 months) and did not significantly differ between MRD-positive (median, 2.3 months; range, 0.6-10.23 months) and MRD-negative (median, 2.4 months; range, 1.1-6.6 months) patients (Figure 1).

MRD negativity preceding relapse is associated with aggressive relapse kinetics

Clinical, genetic, and transplantation-associated characteristics were similarly distributed among MRD-positive and MRD-negative patients, except that MRD-negative patients relapsed significantly more often with FLT3- and WT1-mutated disease (Table 1; supplemental Table 4). The intensity of conditioning therapy did not determine the frequency of MRD positivity before relapse; however, myeloablative conditioning seemed to delay the onset of relapse (supplemental Table 5). Among 59 patients with available diagnostic samples, MRD-negative patients more frequently exhibited adverse risk cytogenetics and a complex karyotype, and gained significantly fewer mutations at relapse compared with MRD-positive patients (supplemental Table 6).

After a median follow-up of 16 months from time of transplantation (range, 2.8-133.7 months), the median CIR was higher for patients who remained MRD negative before relapse compared with patients who became MRD positive before relapse (hazard ratio [HR], 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3-4.1; P < .001) (supplemental Figure 7A). Consistently, median OS from time of transplantation was shorter for patients who remained MRD negative compared with patients who became MRD positive before relapse (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.9-3.02; P = .0068) (supplemental Figure 7B), suggesting faster proliferation of the relapsing clone in MRD-negative patients, leaving less time for MRD detection before relapse. OS from the time of relapse was shorter by trend in MRD-negative patients compared with MRD-positive patients (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.98-3.1; P = .06) (supplemental Figure 7C). Thus, 36% of patients relapsed without an MRD-positive phase, which was associated with rapid disease kinetics and poor survival.

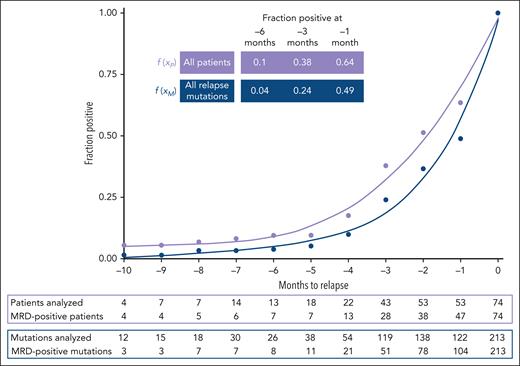

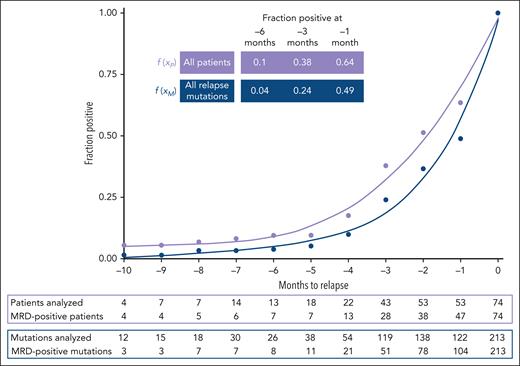

Lead time from MRD detection to relapse

In the 47 MRD-positive patients (64%), the median time to relapse from the first MRD-positive sample was 2.9 months (range, 0.7-14 months). Clone size did not correlate with time to relapse (supplemental Figure 8). The estimated proportion of positive patients and mutations increased exponentially closer to relapse. Thus, at 6 months before relapse, only 10% (4%) of all patients (mutations) were detectable by NGS in PB-MNCs, whereas this fraction increased to 38% (24%) at 3 months and 64% (49%) at 1 month before relapse (Figure 2). Patients who tested MRD positive earlier than 3 months before relapse showed comparable clinical and transplantation-related characteristics to those who became detectable at 3 months or less before relapse (supplemental Table 7). We further evaluated whether early relapsing disease (≤6 months since alloHCT) was genetically distinct from late relapsing disease (>6 months since alloHCT). In 9 patients with early relapse and available data, a median of 100% (range, 33.3%-100%) of their relapse markers were detectable in their first MRD-positive sample. In contrast, in 25 patients with late relapse and available data, a median of 57% (range, 14.3%-100%) of their relapse markers were detectable in their first positive sample. This aligns well with our finding that early relapsing disease represents mostly refractory leukemia, whereas late relapsing disease undergoes clonal evolution with a stepwise acquisition of mutations and different subclonal growth kinetics.

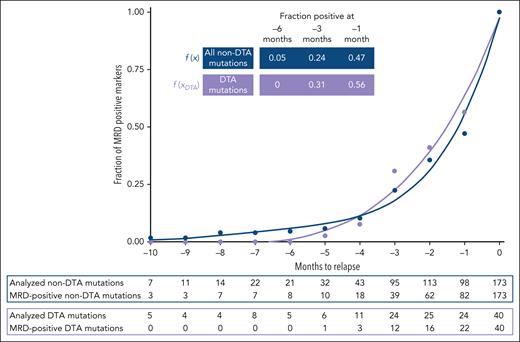

Polynomic curve interpolation of MRD results per patient and per relapse mutation to model relapse dynamics. Full cohort of 74 patients (median, 3 trackable mutations per patient; range, 1-7), mutations in DTA and non-DTA genes were used as MRD markers. Relapse mutations (n = 213) were, if possible, repetitively monitored by NGS-MRD (total number of prerelapse NGS analyses n = 296; median, 1; range, 1-6). MRD status of each marker or each patient was assumed negative until the first sample was measured positive. MRD positivity was assumed for all time intervals following an MRD-positive result until relapse. By calculating the number of positive patients or mutations in a given interval as a fraction of the total number of patients or mutations, we were able to compare relapse kinetics patterns for patients () and mutations (), respectively. , .

Polynomic curve interpolation of MRD results per patient and per relapse mutation to model relapse dynamics. Full cohort of 74 patients (median, 3 trackable mutations per patient; range, 1-7), mutations in DTA and non-DTA genes were used as MRD markers. Relapse mutations (n = 213) were, if possible, repetitively monitored by NGS-MRD (total number of prerelapse NGS analyses n = 296; median, 1; range, 1-6). MRD status of each marker or each patient was assumed negative until the first sample was measured positive. MRD positivity was assumed for all time intervals following an MRD-positive result until relapse. By calculating the number of positive patients or mutations in a given interval as a fraction of the total number of patients or mutations, we were able to compare relapse kinetics patterns for patients () and mutations (), respectively. , .

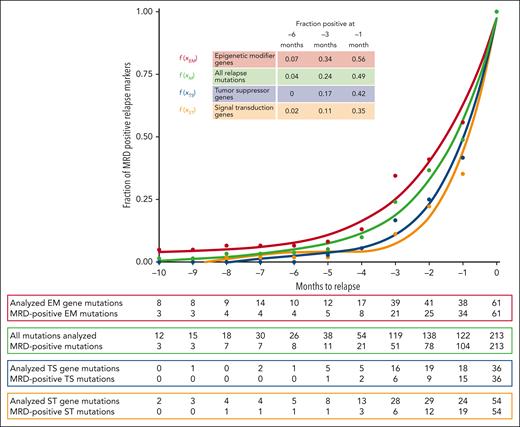

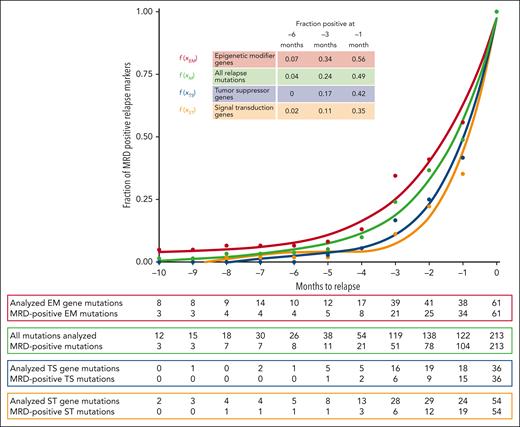

To identify gene-specific differences in relapse kinetics, all 213 relapse mutations were assigned to 1 of 7 functional gene groups (supplemental Table 8). The proportion of positive mutations from all mutations within 1 functional gene group was calculated and plotted against the time to relapse and approximated by fifth-order polynomials. Gene groups with the highest number of mutated genes at relapse were epigenetic modifier (n = 61), tumor suppressor (n = 36), and signaling gene mutations (n = 54), followed by mutations in myeloid transcription factors (n = 26), spliceosome (n = 15), cohesin complex (n = 6), and NPM1 (n = 15) genes. Interestingly, the relapse kinetics of cells with epigenetic modifier gene mutations showed a lower slope than the relapse kinetics of cells with tumor suppressor and especially signaling gene mutations (Figure 3). This could correspond to a longer lead time from detection to relapse when using epigenetic modifier gene mutations than tumor suppressor or signaling gene mutations for MRD monitoring.

Polynomic curve interpolation of MRD results for 3 functional gene classes with the highest number of monitored relapse mutations. EM, epigenetic modifier genes (n = 61); M, all mutations; ST, signal transduction genes (n = 54); TS, tumor suppressor genes (n = 36). See supplemental Table 8 for genes included in these categories. , , .

Polynomic curve interpolation of MRD results for 3 functional gene classes with the highest number of monitored relapse mutations. EM, epigenetic modifier genes (n = 61); M, all mutations; ST, signal transduction genes (n = 54); TS, tumor suppressor genes (n = 36). See supplemental Table 8 for genes included in these categories. , , .

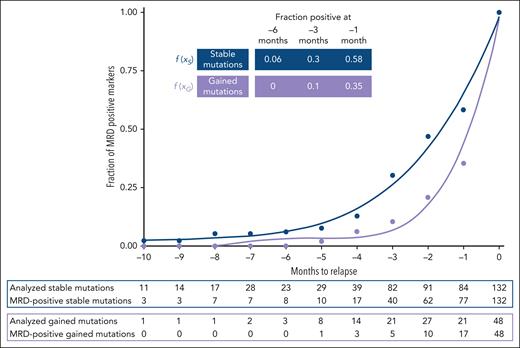

Clonally stable mutations have a longer lead time to relapse than gained mutations

To investigate the relationship between clonal stability on the one hand and MRD positivity on the other for all mutations, we evaluated clonal relapse dynamics in the 59 patients for whom diagnosis and relapse samples were available. Notably, stable mutations (present at diagnosis and relapse) were more often measured as MRD positive (77 of 132, 58%) than gained mutations (present only at relapse) (16 of 48, 33%). Accordingly, stable mutations showed a lower slope than gained mutations when the proportion of positive mutations from all mutations was plotted against the time to relapse and approximated by fifth-order polynomials (Figure 4). For example, at 6 months before relapse, 6% of all stable, but none of the gained, mutations were detectable. At 3 (1) months, detectable stable mutations increased to 30% (58%), whereas gained mutations increased only to 10% (35%). The median time from MRD detection to hematological relapse in patients becoming MRD positive before relapse was 2.6 months (range, 0.6-14 months) using stable mutations for MRD detection and 2 months (range, 0.9-5.4 months) using gained mutations. In summary, clonally stable mutations have a longer lead time to hematological relapse than gained mutations.

Retrospective relapse detection using stable and gained mutations between diagnosis and relapse. Polynomic curve interpolation based on stable mutations (n = 132), which are present at diagnosis and relapse, and gained mutations (n = 48), which are only present at relapse. , .

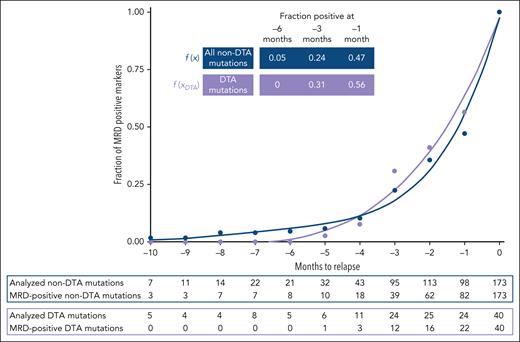

DTA and non-DTA mutations show similar relapse kinetics during follow-up after alloHCT

The most frequently mutated genes in clonal hematopoiesis are DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 (DTA) and were shown to be unsuitable markers for relapse prediction in patients with AML with or without alloHCT.14,25 However, the role of DTA mutations as longitudinal relapse monitoring markers for early relapse detection after alloHCT is still unclear. We hypothesized that the reemergence of cells with DTA mutations in the post-alloHCT setting can identify relapse similarly to non-DTA mutations, as conditioning regimens and alloHCT should have eliminated those cells.

At relapse, 40 DTA mutations were detected in 33 patients and repetitively evaluated by NGS-MRD in prerelapse samples, resulting in a total of 69 prerelapse NGS analyses of DTA mutations (median, 1; range, 1-5 per mutation). Twenty-three (58%) of 40 DTA mutations became MRD positive before relapse. Clinical and transplantation-associated characteristics were similarly distributed between MRD-positive and MRD-negative patients with DTA mutations (supplemental Table 9). In a subgroup analysis of 21 patients with DTA and non-DTA comutations, most (n = 14, 67%) of DTA mutations were detectable at the same time (n = 4, 19%) or earlier (n = 10, 48%) than their non-DTA comutations. Relapse kinetics of MRD-positive patients with or without DTA mutations were similar with a median time to relapse from the first MRD-positive sample to relapse of 2.6 months (range, 0.93-10.27 months) for patients with DTA mutations and 2.6 months (range, 0.7-14.03 months) for patients without DTA mutations (Figure 5). DTA mutations were highly stable without any of the 33 DTA mutations present in patients with available diagnosis sample lost at relapse, whereas only 4 DNMT3A mutations were gained (supplemental Figure 3). The median VAF of DTA-MRD was 0.1%, similar to the 0.083% for non–DTA-MRD comutations, and VAFs correlated well (Pearson correlation coefficient R = 0.51) (supplemental Figure 9). Therefore, the current analysis suggests that MRD relapse can be identified by longitudinal monitoring of DTA mutations after alloHCT similarly to using non-DTA mutations.

Clonal relapse dynamics of patients based on detectable DTA and non-DTA molecular markers. Relapse DTA (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1) and non-DTA mutations were, if possible, repetitively monitored by NGS-MRD. Total number of prerelapse NGS analyses of DTA mutations: n = 69; median, 1; range, 1-5. Total number of prerelapse NGS analyses of non-DTA-mutations: n = 227; median, 1; range, 1-6. , .

Clonal relapse dynamics of patients based on detectable DTA and non-DTA molecular markers. Relapse DTA (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1) and non-DTA mutations were, if possible, repetitively monitored by NGS-MRD. Total number of prerelapse NGS analyses of DTA mutations: n = 69; median, 1; range, 1-5. Total number of prerelapse NGS analyses of non-DTA-mutations: n = 227; median, 1; range, 1-6. , .

Kinetics of MRD and chimerism analysis

The value of MRD and high-sensitivity molecular chimerism analysis for relapse detection was compared in patients for whom at least 2 MRD and 2 chimerism analyses (n = 26) from PB-MNCs were available (supplemental Methods). Fifteen (58%) patients had molecular evidence of relapse before hematologic relapse, whereas in 9 (35%) patients only MRD captured molecular relapse. In 2 patients, neither method detected molecular relapse. Among the 15 patients with relapse detected by both methods, MRD was positive before an increase of host chimerism in 5 patients (33%), with a median lead time of 2.3 months (range, 0.9-9.1 months) compared with chimerism analysis. In 1 patient, host chimerism became positive 0.8 months earlier than MRD analysis. Seven of 15 patients (47%) showed simultaneous positivity for both methods (supplemental Figure 10). In this subset of patients, molecular MRD analysis appeared superior to high-sensitivity chimerism analysis, whereas the clinical value can only be compared in a prospective study.

Discussion

In this study, we reconstructed the molecular architecture and kinetics preceding AML relapse after alloHCT using error-corrected NGS. We investigated 74 patients with AML who relapsed after alloHCT and who had DNA from PB-MNCs available, which had been collected between alloHCT and relapse. Three months before relapse, 38% of patients were MRD positive, whereas this percentage increased to 64% at 1 month before relapse. Mutations in epigenetic modifier genes and stable mutations known from diagnosis, including DTA mutations, provided a longer lead time to relapse and were identified as useful MRD markers after alloHCT.

Detection of impending relapse remains a major challenge in patients with AML. Various tools with different sensitivities, such as multicolor flow cytometry (sensitivity to as low as 0.01%), real-time polymerase chain reaction, and NGS (sensitivity as low as 0.0001%), are available for this purpose. Most studies involving NGS for MRD analysis have been conducted for prognostication, at a time point during induction, at the end of treatment, or before or after alloHCT.14,20,25-31 Less is known about the utility of MRD monitoring for relapse detection in the posttransplant setting. We hypothesized that frequent sampling and MRD analysis before clinical relapse would allow us to reconstruct the molecular kinetics of AML relapse.

In this study, 38% of all patients were MRD positive for at least 1 relapse marker at 3 months before relapse, indicating that a monitoring interval of every 3 months can detect approximately one-third of the relapses. An additional 26% of patients became MRD positive at 2 or 1 months before relapse, necessitating monitoring at intervals shorter than 3 months to successfully detect nearly two-thirds of the relapsing patients (64%). Additional analyses from bone marrow samples would be required to characterize the relapse kinetics of the 30% of patients who remained MRD negative at 3 months or closer to relapse, which were unfortunately unavailable in our study. The relapse samples of patients who remained MRD negative predominantly displayed mutations in FLT3-ITD, TP53, WT1, and DNMT3A genes. A small subset of patients (6%) who remained MRD negative had their last MRD sample taken at 4 or 5 months before relapse. For these individuals, we cannot make assumptions regarding the optimal monitoring interval because of the missing samples closer to relapse.

We show that epigenetic modifier genes represent the most stable mutations from diagnosis to relapse and that MRD assessment using epigenetic modifier gene mutations demonstrated the longest lead time to relapse. Therefore, these genes fulfill the criteria for a suitable MRD marker for longitudinal MRD assessment after alloHCT.

In contrast and as previously described, mutations in signaling genes, especially mutations in NRAS and FLT3, were rather unstable from diagnosis to relapse.32,33 For example, 8 (20%) of the 40 patients who were FLT3-ITD negative at diagnosis gained the mutation and 3 (17%) of the 18 patients who were FLT3-ITD positive at diagnosis lost the mutation at relapse. This proportion is significant, but smaller compared with the 46% of patients treated with midostaurin in the Ratify trial who lost the FLT3 mutation at relapse.34 None of the 28 patients with FLT3-ITD–positive disease received FLT3-targeted therapies after alloHCT and before hematological relapse.

In the present study, in addition to clonal instability, MRD relapse could not be identified using FLT3-ITD as an MRD marker in a significant proportion of FLT3-ITD–mutated patients (18 of 28, 64%). In contrast, NGS-MRD for FLT3-ITD has recently been established by several groups as a highly prognostic marker after chemotherapy or before alloHCT,30,35,36 suggesting that FLT3-ITD as a post-alloHCT MRD marker needs further evaluation.

Similar to mutations in signal transduction genes, mutations in the tumor suppressor gene WT1 exhibited clonal instability, with 8 WT1 relapse mutations newly emerging at relapse. These mutations remained undetectable by MRD in 13 of 14 patients experiencing WT1-mutated relapse (93%).

In our study, mutations from diagnosis expressed a high degree of stability throughout the course of the disease. Conversely, 27% of relapse mutations were newly acquired. Encouragingly, the stable mutations were more frequently detectable as MRD before hematologic relapse (58%), whereas only 34% of the gained mutations were MRD positive before relapse. Of all mutations, TP53 relapse mutations exhibited the highest degree of stability, with only 1 of 11 TP53 relapse mutations being newly aquired.

In 26 CR patients, MRD could be evaluated before alloHCT and was correlated with prerelapse MRD status (data not shown). A similar proportion of patients who were MRD positive or negative before alloHCT had detectable prerelapse MRD (72% vs 63%, respectively), suggesting that MRD status before alloHCT does not correlate well with prerelapse MRD.

Considering the instability of clones throughout treatment, we evaluated the possibility that relapse with a distinct mutational pattern might in fact be of donor origin. In our cohort, 93% (69 of 74) of patients had consistent mutations or cytogenetic abnormalities at diagnosis and relapse. Among the 5 patients lacking diagnostic data, 3 had strongly reduced donor chimerism at relapse, likely ruling out donor-cell origin. Two patients had rapid relapse post-alloHCT, not aligning with expected donor-cell leukemia timing. Thus, we confidently exclude donor-derived leukemia in our MRD analyses. None of our MRD-monitored patients exhibited characteristics consistent with donor-derived clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, such as a decreasing VAF toward relapse of a gene variant not present at diagnosis.

In the alloHCT setting, it is conceivable that the reappearance of recipient cells after transplant, including markers of clonal hematopoiesis, indicates relapse. In a previous study, we showed that non-DTA MRD positivity at day 90 and/or day 180 post-alloHCT was an independent adverse predictor of CIR, relapse-free survival, and OS, whereas DTA mutations at these time points had no prognostic impact.14 However, in the current study, we demonstrate that serial MRD monitoring after alloHCT using DTA mutations can effectively identify relapse, similar to non-DTA mutations. Although this study lacks information on the role of DTA-MRD after alloHCT in patients who did not experience relapse, a recent study by Bischof et al illustrates the prognostic significance of measurable residual clonal hematopoiesis detected by droplet digital polymerase chain reaction in patients with AML post-alloHCT.37 Supporting our observations, they found that positive measurable residual clonal hematopoiesis at 80, 100, 180, and 360 days after alloHCT correlated with increased relapse incidence and shorter event-free survival at all time points analyzed, along with shorter OS at 28 and 100 days post-alloHCT.

Intriguingly, our study revealed a notable paradox, as patients without detectable MRD before hematologic relapse exhibited a swifter relapse onset and shorter OS from the time of alloHCT compared with MRD-positive patients. Evidently, the MRD monitoring interval in these patients was longer than the time from molecular detection to relapse, suggesting the presence of a rapidly growing AML clone. To detect MRD ahead of relapse in such patients in the future, a more suitable source of cells should be evaluated, such as bone marrow or cell-free DNA, alongside a more sensitive MRD technique and a shorter monitoring interval.

A comparison between relapse detection by MRD and high-sensitivity chimerism from PB-MNCs in a subset of 26 patients showed that MRD by NGS detected the relapse more often and earlier than high-sensitivity chimerism (supplemental Figure 10), suggesting that NGS-MRD can improve the current post-alloHCT monitoring strategy in patients with informative MRD markers.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective study design limited the availability of samples; consequently, we lack information on clone doubling times and, for some patients, individual mutation relapse kinetics. Although peripheral blood was chosen for its accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and lower patient invasiveness, there is no agreement regarding sensitivity of peripheral blood MRD analysis compared with bone marrow.16,38,39 Thus, a prospective study involving paired bone marrow and peripheral blood sampling for MRD assessment is warranted to address these limitations comprehensively. In addition, a substantial number of patients with isolated extramedullary recurrence had to be excluded because of the lack of an established MRD monitoring approach for this subgroup. Nevertheless, early investigations suggest promising results for using serum circulating tumor DNA as a potential tool for prognostication and, potentially, remission monitoring in patients with extramedullary onset of AML.40,41

In summary, this study shows that 38% of AML relapses after alloHCT can be detected by NGS-based MRD monitoring from peripheral blood using an interval of every 3 months, whereas 64% of patients with AML relapse can be detected with a monthly monitoring interval. Mutations in epigenetic modifier genes, including DTA mutations, were identified as useful relapse monitoring markers, as they were stable MRD markers with a sufficient lead time to relapse. In addition, mutations known from diagnosis were detectable with longer lead time to relapse than emerging mutations. Thus, NGS-MRD monitoring from peripheral blood in monthly intervals after alloHCT using the known mutations from diagnosis is a valid strategy to detect most AML relapses before hematologic relapse.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung grant 16 R/2021 (M.H.), Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung grants 70114478, 70114706 (M.H.), and 01GM1909A (F.T.), and Deutsche Krebshilfe grant 70113945 (C.P.W.).

The visual abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Authorship

Contribution: C.P.W., F.T., and M.H. designed the study; C.P.W., B.H., L.V., K.K., K.T., K.B., M.W., W.P., B.N., M.R., E.D., M.S., A.G., L.H., F.T., and M.H. contributed to the collection of clinical and biological data; C.P.W., B.H., L.V., R.G., K.T., K.B., M.W., W.P., B.N., M.R., E.D., M.S., A.G., L.H., F.T., and M.H. contributed to the analysis of clinical and biological data; C.P.W., R.G., and M.H. performed the statistical analysis; C.P.W. and M.H. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.H. declares honoraria from Certara, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Novartis, and Sobi; paid consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Glycostem, LabDelbert, Pfizer, PinotBio, and Servier; and research funding to his institution from AbbVie, Agios, Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Glycostem, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm, Loxo Oncology, and PinotBio. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Heuser, Department of Hematology, Hemostasis, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg Str 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany; email: heuser.michael@mh-hannover.de.

References

Author notes

F.T. and M.H. contributed equally to this study.

Presented in part at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, 11-14 December 2021.

Patient-level data are not publicly available to comply with privacy protection laws. Reasonable requests for original data should be addressed to the corresponding author, Michael Heuser (heuser.michael@mh-hannover.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal