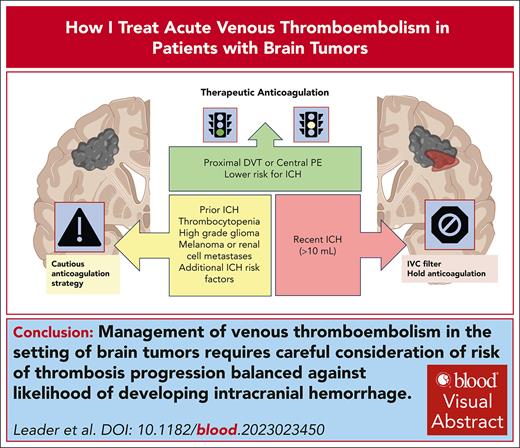

Visual Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication in patients with brain tumors. The management of acute VTE is particularly challenging due to an elevated risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). Risk of developing ICH on anticoagulation is influenced by a number of factors including tumor type, recent surgery, concomitant medications, platelet counts, and radiographic features. In patients with a heightened risk for ICH, the benefits of anticoagulation need to be balanced against a likelihood of developing major hemorrhagic complications. Management decisions include whether to administer anticoagulation, at what dose, placement of an inferior vena cava filter, monitoring for development of hemorrhage or progressive thrombus, and escalation of anticoagulant dose. This article discusses the complexities of treating acute VTE in patients with brain tumors and outlines treatment algorithms based on the presence or absence of ICH at the time of VTE diagnosis. Through case-based scenarios, we illustrate our approach to anticoagulation, emphasizing individualized risk assessments and evidence-based practices to optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing the risks of hemorrhagic events in patients with brain tumors.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) represents a serious complication of cancer specifically in patients with brain tumors. Although 2% to 11% of patients with active malignancy develop VTE, the rate is 2 to 3 times higher for brain tumors.1-3 The incidence of VTE is particularly high in patients with high-grade glioma, with a pooled incidence of 16.1% in a recent meta-analysis and as high as 30% to 50% in individual studies.4 The VTE incidence varies among patients with brain metastases, according to the type of primary tumor.1

The basis for thrombosis in cancer is multifactorial, including the elaboration of prothrombotic factors from tumor cells such as tissue factor and podoplanin, activation of immune response (ie, neutrophil extracellular traps), and clinical features such as anticancer treatment (eg, surgery, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapies), advanced age, comorbid conditions, and immobility.5-8 Although there is high-quality evidence for the efficacy and safety of either low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in the management of cancer-associated thrombosis,9,10 the administration of anticoagulants in patients with primary or secondary brain tumors poses unique challenges and considerations. Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is common in patients with brain tumors, complicating decisions regarding whether and when to start anticoagulation, which type of anticoagulant, at what dose, duration, as well as how to monitor for evidence of complications.

Most randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy and safety of LMWH and DOACs for cancer-associated VTE did not exclude patients with known brain tumors; however, only 151 patients (84 with LMWH; 67 with DOACs) with known brain tumors were included across 6 trials, and bleeding was often not reported in the brain tumor subgroup.10-15 Accordingly, there is no level 1 evidence favoring one anticoagulant over another for the treatment of VTE in patients with brain tumors. Therefore, decision-making relies upon observational data and expert opinion. Evidence-based recommendations outlined by the American Society of Hematology and the American Society of Clinical Oncology provide guidance on the prevention and management of acute VTE in patients with cancer, tailored to specific scenarios including anticoagulant selection in ambulatory vs hospitalized patients, perioperative patients, and those within validated intermediate high-risk VTE groups.3,16-19 These guidelines, however, are not specific to patients with brain tumors who have unique considerations. In these patients, the benefits of anticoagulation for acute VTE must be balanced against the potential risk of ICH, which is primarily intratumoral.

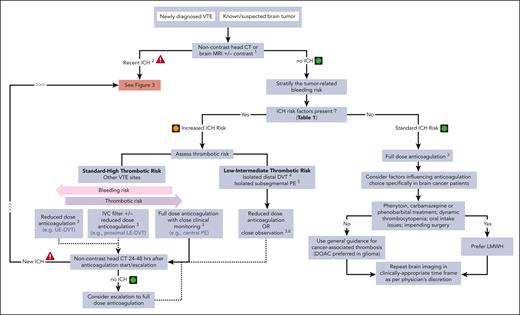

This “How I Treat” summarizes current data on hemorrhagic risk in patients with brain tumors and provides insight into how we approach anticoagulant management for acute VTE in different challenging clinical scenarios. Figure 1 shows our general approach toward the management of patients with brain tumors in whom anticoagulation is being considered for acute VTE. A risk-benefit assessment starts with 2 basic questions: (1) what is the likelihood of a serious embolic event in the absence of anticoagulation? and (2) what is the risk of hemorrhage with the initiation of anticoagulation?

Management of acute VTE in patients with brain cancer, without recent ICH2.1Noncontrast head CT or brain MRI with and without contrast for preanticoagulation baseline assessment, if no imaging within preceding 2 weeks. 2Recent ICH defined as imaging evidence of ICH in past 30 days. Hemosiderin residues (usually intratumoral) are not considered to be recent ICH. 3Discuss risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulation and alternatives with patient and/or health care proxy and document before treatment initiation. 4Isolated distal DVT refers to calf vein DVT without known PE (and without clinical suspicion of PE). 5Isolated subsegmental PE refers to isolated subsegmental PE and absence of DVT on bilateral lower extremity ultrasound doppler. 6Close observation without anticoagulation includes lower extremity ultrasound doppler after 1 week (consider repeat in 2 weeks) to exclude new DVT or proximal DVT progression. LE, lower extremity; UE, upper extremity.

Management of acute VTE in patients with brain cancer, without recent ICH2.1Noncontrast head CT or brain MRI with and without contrast for preanticoagulation baseline assessment, if no imaging within preceding 2 weeks. 2Recent ICH defined as imaging evidence of ICH in past 30 days. Hemosiderin residues (usually intratumoral) are not considered to be recent ICH. 3Discuss risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulation and alternatives with patient and/or health care proxy and document before treatment initiation. 4Isolated distal DVT refers to calf vein DVT without known PE (and without clinical suspicion of PE). 5Isolated subsegmental PE refers to isolated subsegmental PE and absence of DVT on bilateral lower extremity ultrasound doppler. 6Close observation without anticoagulation includes lower extremity ultrasound doppler after 1 week (consider repeat in 2 weeks) to exclude new DVT or proximal DVT progression. LE, lower extremity; UE, upper extremity.

Case-based management approach

Case 1

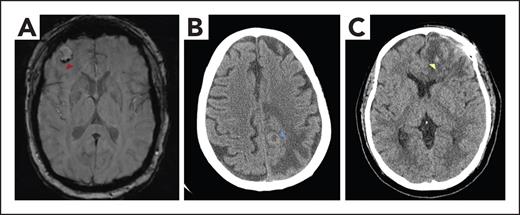

A 52-year-old woman, former smoker with hypertension, was diagnosed with stage IV non–small cell lung cancer (epidermal growth factor receptor wildtype/KRAS wild-type), including several brain metastases. She was treated with brain stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), as well as carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab with systemic response. Three months into the treatment, after mild dyspnea on exertion and hypoxia, a computed tomography (CT) scan chest pulmonary embolism (PE) protocol revealed a new left segmental PE. Bilateral lower extremity venous dopplers showed a new left femoral deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Vital signs were notable for a blood pressure of 133/65 mm Hg, a pulse of 124 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and a pulse oximetry reading of 90% on room air. She had a normal neurologic examination. Platelets, renal and hepatic function, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and prothrombin time (PT) were normal. Echocardiogram did not show right-heart strain. Consult request was as follows: hematology was consulted to assess whether full dose-anticoagulation should be administered in a patient with brain metastases. Hematology assessment was as follows: because the last intracranial imaging was 6 weeks before presentation, she underwent repeat brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast, which showed a stable, treated intracranial metastasis with minimal vasogenic edema and mild stable hemosiderin deposition, consistent with chronic minor blood products (Figure 2A). The patient was assessed to have an increased, but not prohibitive, risk of ICH due to hemosiderin deposition and bevacizumab use. Conversely, the brain metastases were considered effectively treated with SRS. Considering her acute symptomatic segmental PE and proximal DVT, therapeutic-dose anticoagulation was started with apixaban 10 mg twice daily for 1 week, followed by 5 mg twice daily. She also continued her anticancer therapy. Surveillance noncontrast CT scan of brain after 48 hours and 2 weeks did not show evidence of ICH.

Imaging of patients with brain tumors with or without ICH. (A) MRI brain axial susceptibility weighted image demonstrating a right frontal brain metastasis with mild peripheral hemosiderin deposition (red arrowhead), consistent with chronic hemorrhage. (B) Noncontrast CT brain axial image revealing a peripherally hyperdense lesion (blue arrowhead) with surrounding confluent hypodensity in the left posterior frontal lobe, consistent with a brain metastasis and vasogenic edema. The hyperdense rim represents high cellularity within the tumor. (C) Noncontrast CT brain axial image showing left frontal postoperative change status after glioblastoma resection, with hypodense vasogenic edema and scattered foci of hyperdensity (yellow arrowhead) consistent with subacute blood products.

Imaging of patients with brain tumors with or without ICH. (A) MRI brain axial susceptibility weighted image demonstrating a right frontal brain metastasis with mild peripheral hemosiderin deposition (red arrowhead), consistent with chronic hemorrhage. (B) Noncontrast CT brain axial image revealing a peripherally hyperdense lesion (blue arrowhead) with surrounding confluent hypodensity in the left posterior frontal lobe, consistent with a brain metastasis and vasogenic edema. The hyperdense rim represents high cellularity within the tumor. (C) Noncontrast CT brain axial image showing left frontal postoperative change status after glioblastoma resection, with hypodense vasogenic edema and scattered foci of hyperdensity (yellow arrowhead) consistent with subacute blood products.

Risk factors associated with elevated ICH risk in patients with brain tumors

Stratifying the risk of ICH in patients with primary and secondary brain tumors is complex. Table 1 provides a list of potential factors that contribute to the risk of ICH. Brain metastases are associated with a higher baseline ICH risk (ie, without anticoagulation) than primary brain cancer; 15.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.3-37.2) compared with 4.4% (95% CI, 2.5-7.7).36 On the contrary, anticoagulation has been associated with increased ICH risk in patients with primary brain cancer (12.5% [95% CI, 8.0-18.8]; relative risk [RR], 2.58 [95% CI, 1.59-4.19]) but not in patients with brain metastases (14.7% [95% CI, 4.4-39.2]; RR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.45-1.65]).36 The ICH incidence in patients with brain metastases differs greatly between different primary cancer types.34 The highest rates of symptomatic and asymptomatic ICH have been documented in patients with brain metastases from melanoma (15%-45%),37,38 thyroid cancer (60%),39 renal cell carcinoma,40-42 and choriocarcinoma.43,44 Although patients with melanoma or renal cell carcinoma brain metastases had a fourfold higher ICH incidence than other cancer types, the 1-year cumulative incidence of ICH was similar in patients with matched melanoma or renal cell carcinoma with (35%) or without (34%) enoxaparin anticoagulation.34 We acknowledge that the retrospective nature of the above studies does not completely exclude an increased risk of anticoagulation in patients with brain metastases. Nonetheless, because studies using the same methodology have identified a clear increased risk in patients with high-grade glioma and not in those with brain metastases,20,45 we hypothesize that any additive relative risk is likely to be modest. We do, however, exercise caution in patients with high ICH risk brain metastasis types such as renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, because even small relative increases in ICH risk may translate into a clinically relevant absolute increase in risk.

Potential ICH risk factors in patients with brain tumors receiving anticoagulation

| Group . | Variables . | Comment . | Anticoagulation ICH risk ∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | High-grade glioma | LMWH, but not DOAC, has been associated with increased ICH risk.20 | Intermediate |

| Melanoma Renal cell carcinoma Thyroid cancer Choriocarcinoma | Increased ICH risk independent of anticoagulation administration21 | Uncertain | |

| Brain tumor location | Intraventricular or convexity location in meningiomas | Increased spontaneous ICH demonstrated on retrospective review22 | Uncertain |

| Prior ICH | Prior intratumoral hemorrhage on imaging | Preexisting intratumoral hemorrhage increased the risk of recurrent ICH after stereotactic radiosurgery.23,24 ICH risk low in patients who resumed anticoagulation in setting of hemosiderin25 | Uncertain |

| Larger ICH (≥10-mL volume) | Cohort of 16 patients with brain tumors, recurrent ICH in 2 patients following anticoagulation restart25 | Higher | |

| Platelet count | <50 x 109/L | Full-dose anticoagulation is not recommended in patients with platelets <50 x 109/L.26 | Higher |

| <100 x 109/L | Emerging data that mild thrombocytopenia (<100 x 109/L) associated with increased bleeding risk27-29 | Intermediate | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | Combined with anticoagulation | Antiplatelet therapy alone does not appear to increase risk of ICH in brain tumors.30,31 | Intermediate |

| VEGF inhibitors | Potential risk of ICH in glioma but less evidence with brain metastases32,33 | Uncertain | |

| Chronic kidney disease | Established risk factor for anticoagulant hemorrhage with some evidence in patients with brain metastases on anticoagulation34 | Uncertain | |

| Stereotactic radiosurgery | Potential ICH risk factor with35 and without35 anticoagulation in small cohorts of patients with melanoma brain metastases | Uncertain |

| Group . | Variables . | Comment . | Anticoagulation ICH risk ∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | High-grade glioma | LMWH, but not DOAC, has been associated with increased ICH risk.20 | Intermediate |

| Melanoma Renal cell carcinoma Thyroid cancer Choriocarcinoma | Increased ICH risk independent of anticoagulation administration21 | Uncertain | |

| Brain tumor location | Intraventricular or convexity location in meningiomas | Increased spontaneous ICH demonstrated on retrospective review22 | Uncertain |

| Prior ICH | Prior intratumoral hemorrhage on imaging | Preexisting intratumoral hemorrhage increased the risk of recurrent ICH after stereotactic radiosurgery.23,24 ICH risk low in patients who resumed anticoagulation in setting of hemosiderin25 | Uncertain |

| Larger ICH (≥10-mL volume) | Cohort of 16 patients with brain tumors, recurrent ICH in 2 patients following anticoagulation restart25 | Higher | |

| Platelet count | <50 x 109/L | Full-dose anticoagulation is not recommended in patients with platelets <50 x 109/L.26 | Higher |

| <100 x 109/L | Emerging data that mild thrombocytopenia (<100 x 109/L) associated with increased bleeding risk27-29 | Intermediate | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | Combined with anticoagulation | Antiplatelet therapy alone does not appear to increase risk of ICH in brain tumors.30,31 | Intermediate |

| VEGF inhibitors | Potential risk of ICH in glioma but less evidence with brain metastases32,33 | Uncertain | |

| Chronic kidney disease | Established risk factor for anticoagulant hemorrhage with some evidence in patients with brain metastases on anticoagulation34 | Uncertain | |

| Stereotactic radiosurgery | Potential ICH risk factor with35 and without35 anticoagulation in small cohorts of patients with melanoma brain metastases | Uncertain |

∗ Additive ICH risk with anticoagulation.

The risk of intracranial bleeding is influenced by not only the malignancy but also several dynamic variables including the acuity of preexisting ICH, stability of intracranial tumor burden, SRS,35,37 coexisting thrombocytopenia or other coagulopathies, certain medications (eg, antiplatelet therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] inhibitors), uncontrolled hypertension, concurrent renal and/or liver dysfunction, functional status, and fall risk (Table 1).46,47 Although VEGF inhibitors are associated with an increase in major bleeding, including reports of intracranial bleeding, a larger meta-analysis did not identify an elevated ICH risk in patients with solid tumor brain metastases receiving bevacizumab.32,48 On the contrary, there are reports suggesting an increase in ICH risk among patients with glioblastoma receiving bevacizumab and anticoagulation compared with bevacizumab alone.33 In general, the use of bevacizumab does not preclude anticoagulation, and there are no recommendations regarding changes in anticoagulant dosing in the setting of concurrent treatment with antiangiogenics and anticoagulants. Considering the conflicting data and the proven association with increased systemic bleeding, we consider VEGF inhibitors as a possible ICH risk factor in brain cancer patients receiving anticoagulation, especially in combination with additional risk factors.

Current guidelines suggest full-dose anticoagulation for cancer-associated thrombosis when platelets are >50 x 109/L, in the absence of bleeding or additional risk factors.26,49 Potentially challenging this concept, recent studies demonstrated an increased risk of major bleeding and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding in patients with platelets <100 x 109/L (compared with higher platelet counts) receiving anticoagulation for VTE or atrial fibrillation.27,28 This may reflect an actual bleeding risk with platelet counts ranging from 50 x 109/L to 100 x 109/L but also could identify those with subsequent more severe platelet nadir or underlying disease contributing to thrombocytopenia (ie, liver disease). In patients with spontaneous ICH, mild thrombocytopenia is considered a risk factor for hematoma expansion.29 In patients with brain cancer, we generally hold or modify anticoagulation dosing when platelets are <50 x 109/L and consider patients with platelets 50 x 109/L to 100 x 109/L to be at an increased (but not prohibitive) bleeding risk, especially in the presence of additional bleeding risk factors.

All these factors must be considered carefully with expert guidance, with no clinically validated scoring systems available specific to the brain tumor population.

Case 2

A 60-year-old right-handed man with advanced stage IV renal cell carcinoma, receiving first-line nivolumab and cabozantinib for 4 weeks, presented to the emergency room with a first-time focal motor seizure, characterized by right arm and face convulsions lasting 3 minutes. Vital signs, PT, and PTT were normal. Platelets were 85 x 109/L. CT scan of brain without contrast revealed a peripherally hyperdense lesion in the left-frontal lobe, consistent with a brain metastasis, without evidence of acute hemorrhage (Figure 2B). Due to new left-calf edema, bilateral lower extremity venous dopplers revealed new left-calf DVT. CT chest PE protocol demonstrated increased retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and pulmonary metastases, without evidence of PE. Consult request was as follows: hematology and neurology were consulted to discuss safety of anticoagulation in the setting of newly diagnosed brain metastasis in a patient with renal cell carcinoma at higher risk for ICH. Hematology assessment was as follows: the patient was considered to have an increased risk of anticoagulation-associated ICH due to newly diagnosed renal cell carcinoma brain metastasis as well as thrombocytopenia. The presence of an isolated distal DVT was assessed to be at a low-intermediate risk for progression and PE. Initially prescribed reduced dose of enoxaparin at 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. The patient then underwent SRS for the multiple brain metastases and was discharged home. A noncontrast brain CT scan at 2 weeks did not demonstrate evidence of acute ICH, and the patient remained symptomatic with left-calf edema and pain. Planned surveillance ultrasound doppler did not demonstrate progression of the left-calf DVT. He was transitioned to full-dose enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily with a plan to repeat noncontrast brain CT scan 48 hours later.

Identifying patients at increased risk of thrombus progression or embolization

Patients with intracranial tumors may suffer from hemiparesis or limited mobility, which contribute to the VTE risk. The prognosis of the underlying cancer in this setting often means that cancer-associated hypercoagulability and the corresponding VTE risk is likely to persist over a patient’s lifetime. Although anticoagulation-associated ICH in patients with brain tumor could have dire outcomes, the risks of withholding anticoagulation carry serious consequences such as venous clot propagation with worsening symptoms and the risk for potentially fatal PE. As outlined, the goal is to identify the risk of thrombus progression and balance the risks associated with anticoagulation. Two well-known examples of potentially lower-risk VTEs are isolated distal DVT (ie, DVT in the calf veins only, without known radiological evidence of PE) or isolated subsegmental PE (ie, lower extremity DVT ruled out by screening ultrasound doppler). However, the relatively favorable outcomes among the general population, even without anticoagulation, may be less generalizable in patients with malignancy.50,51

The rate of extension of an isolated distal DVT in the absence of anticoagulation is between 10% and 20%.52 Although there is evidence that anticoagulation can reduce the development of recurrent DVT, there is no clear benefit in terms of reduction of PE.52 A recent study of the general population (excluding patients with cancer) with distal DVT demonstrated a reduction in recurrent isolated distal DVT with 12 weeks anticoagulation compared with 6 weeks, with similar rates of proximal DVT and PE.53 Patients with cancer with isolated distal DVT have a higher VTE recurrence risk than patients without cancer. In the Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad TromboEmbolica (RIETE) registry, the rates of recurrent VTE on anticoagulation were similar in patients with cancer with isolated distal DVT and proximal DVT.54 However, there were 19 cases of fatal PE in patients with proximal DVT compared with 0 in the isolated DVT cohort.54 Although the recurrent VTE risk may be similar among patients with cancer with proximal DVT and isolated distal DVT,55 the lower risk of PE supports the decision to withhold anticoagulation in patients at risk for major hemorrhagic complications.

Among patients with isolated subsegmental PE, the risk of recurrent VTE without anticoagulation is fairly modest. A recent prospective cohort study of 266 patients (without active cancer) with isolated subsegmental PE not treated with anticoagulation demonstrated a 90-day cumulative VTE incidence of 3.1% (95% CI, 1.6-6.1), with a higher incidence (5.7%) in patients with multiple isolated subsegmental PEs but no fatal recurrent PEs.51 In another observational study of patients with isolated subsegmental PE (44% of whom had active cancer), only 1 of 41 patients who did not receive anticoagulation developed recurrent VTE at 1 year. The recurrence rate was similar in 77 patients initially treated with anticoagulation.56 Of note, in a prospective cohort of 292 patients with subsegmental PE who underwent bilateral lower extremity ultrasound doppler at baseline and again (if negative) by day 7, DVT was identified in 18 patients (6.2%) on initial and 10 patients (3.4%) on repeat ultrasound doppler.51 This supports the practice of performing baseline and repeat lower extremity screening ultrasound doppler in patients with subsegmental PE without known DVT when not receiving full-dose anticoagulation.

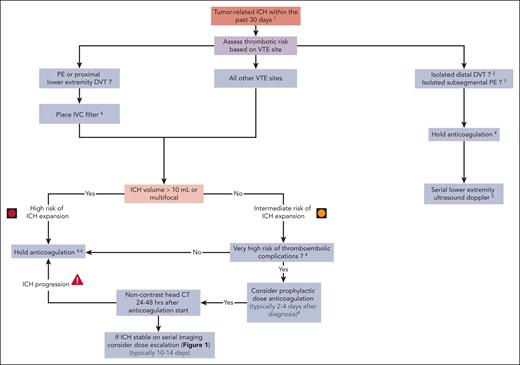

Taken together, we generally consider cancer-associated isolated distal DVT, isolated subsegmental PE, and other comparably lower-risk VTEs (such as some cases of catheter-related upper extremity DVT57,58) to have a clinically relevant risk of progression, but the sites and nature of recurrence are less commonly life threatening. We weigh these risks against the ICH rates, which are at least comparable in some patients with brain cancer (as detailed above) and may have serious clinical consequences. Therefore, we often recommend dose-reduced anticoagulation (or withhold completely) in patients with brain tumors and higher ICH risk in the setting of acute isolated distal DVT or isolated subsegmental PE but aim to gradually dose escalate anticoagulation as feasible (Figure 1). In such patients with recent ICH, we would usually withhold anticoagulation and do not place an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter (Figure 3). We use serial surveillance lower extremity ultrasound dopplers to assess for proximal DVT if anticoagulation is held in patients with acute isolated distal DVT or isolated subsegmental PE.

Management of acute VTE in patients with brain cancer, with recent ICH.1Excluding hemosiderin residues (usually intratumoral) as the sole finding. 2Isolated distal DVT refers to calf vein DVT without known PE (and without clinical suspicion of PE). 3Isolated subsegmental PE refers to isolated subsegmental PE without DVT on bilateral lower extremity ultrasound doppler (which is mandatory). 4Discuss risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulation and alternatives with patient and/or health care proxy and document before treatment initiation. 5Lower extremity ultrasound doppler after 1 week (and possibly again at 2 weeks) to exclude new DVT or proximal DVT progression. 6Periodically reassess risk-benefit of initiating anticoagulation.

Management of acute VTE in patients with brain cancer, with recent ICH.1Excluding hemosiderin residues (usually intratumoral) as the sole finding. 2Isolated distal DVT refers to calf vein DVT without known PE (and without clinical suspicion of PE). 3Isolated subsegmental PE refers to isolated subsegmental PE without DVT on bilateral lower extremity ultrasound doppler (which is mandatory). 4Discuss risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulation and alternatives with patient and/or health care proxy and document before treatment initiation. 5Lower extremity ultrasound doppler after 1 week (and possibly again at 2 weeks) to exclude new DVT or proximal DVT progression. 6Periodically reassess risk-benefit of initiating anticoagulation.

Anticoagulation selection in patients with brain metastases

Our group and others performed retrospective cohort studies to evaluate whether DOACs are a safe alternative to LMWH in patients with brain metastases.59,60 We performed a recent meta-analysis that included 979 patients with brain metastases treated with DOACs (n = 359) or LMWH (n = 620) for any indication and did not identify a difference in the ICH risk between the anticoagulant groups (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.71-1.56).20 These findings remained consistent for fatal ICH. The cumulative incidence of ICH in the DOAC-treated group was 11.4% compared with 11.6% in those receiving LMWH. Accordingly, we consider both DOACs and LMWH as viable treatment options in patients with brain metastases and acute VTE. The DOACs we consider for use are apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban because the efficacy and safety of these agents for treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis has been shown in clinical trials.9,10,13 We assess relevant drug-drug interactions and are vigilant of interactions between DOACs and antiseizure medications that may induce cytochrome P-450 and/or p-glycoprotein, leading to lower DOAC levels. Of note, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital usually preclude the use of apixaban and rivaroxaban (and often edoxaban).61-63 Antiseizure medication such as levetiracetam and lacosamide appear to be acceptable for concurrent use with DOACs.63,64 We take additional variables specific to patients with brain cancer into account (eg, oral intake issues) and follow general guidelines for the treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis, when selecting the optimal anticoagulant type (Figure 1).

ICH imaging characteristics

Intratumoral hemorrhage occurs in patients with primary and metastatic brain tumors due to dysfunctional thin-walled tumor vasculature and intratumoral necrosis.65 CT and MRI provide complementary information regarding the age and volume of intratumoral bleeding.66 CT brain is often the initial imaging of choice in suspected ICH in both the cancer and noncancer populations, given the speed of scan duration and classic appearance of acute hyperdense blood relative to the brain parenchyma. Hyperdense blood products will peak within hours of ICH on CT brain, then gradually become more isodense over subsequent days to weeks as the blood resorbs.66 Bleeding may be challenging to distinguish from an underlying brain mass on CT, because primary and secondary brain tumors may appear hypodense, isodense, or hyperdense, irrespective of the presence of intratumoral blood products, and with increasing density often a sign of high cellularity. Intratumoral calcifications may also appear hyperdense and may mimic small areas of punctate hemorrhage. Therefore, CT brain imaging in monitoring intratumoral hemorrhage is the most useful over serial scans, in which the relative density of the underlying mass has been established. MRI, alternatively, provides enhanced ability to age ICH due to varying paramagnetic properties of evolving hemoglobin states (oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, ferritin, and hemosiderin), which is of particular relevance when weighing safety of anticoagulation on the chronicity of hemorrhage. In the case of bland hemorrhage, comparison of blood intensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images can reasonably distinguish between hyperacute (<1 day), acute (1-3 days), early subacute (3-7 days), late subacute (7-28 days), and chronic (>28 days) hemorrhage.67 Magnetic resonance susceptibility-weighted imaging, a type of gradient echo sequence, may also identify small or early hemorrhages and late-stage blood products, although due to blooming artifact can overestimate the degree of hemorrhage. Intratumoral hemorrhage shares these characteristics, however must be interpreted against the background of generally T1-hypointense/isointense and T2-hyperintense brain tumors and possibly concurrent necrosis. Cystic cavities within tumors may contain layering blood products, particularly among highly hemorrhagic malignancies such as melanoma and renal cell carcinoma. Hemorrhage within brain tumors is often of mixed ages, because tumors may bleed several times over a patient’s lifetime, in conjunction with factors such as change in tumor size, coagulopathies, and concurrent medication use. Often, nonspecific and asymptomatic small volume hemosiderin deposition is identified in primary and secondary brain tumors, which is not a strict contraindication to anticoagulation in isolation but should be monitored. Review of complex imaging with a neuroradiologist may be helpful to track the evolution of intratumoral hemorrhage and inform anticoagulation decisions.

Case 3

A 76-year-old right-handed woman with a left frontal glioblastoma was treated with left frontal craniotomy and subsequent radiation and concurrent temozolomide. Three weeks after completing radiation, she presented to the emergency room with 2 weeks of confusion, progressive aphasia and bilateral lower extremity edema, and weakness. Physical examination was notable for a mild mixed expressive and receptive aphasia, bilateral proximal leg weakness, a wide-based unsteady gait, and right posterior distal thigh and calf tenderness with 2+ pitting edema. Vital signs, platelet count, PT, and PTT were normal. CT brain without contrast revealed increased left frontal vasogenic edema with subacute hemorrhage at the site of the resected tumor (Figure 2C). The neurosurgery consultant did not identify an indication for acute intervention. Bilateral lower extremity venous dopplers demonstrated a DVT in the right femoral, popliteal, and tibial veins. Consult request was as follows: neurology and hematology were consulted to discuss the management of acute right proximal lower extremity DVT in the setting of subacute ICH. Hematology assessment was as follows: a decision was made to place an IVC filter given the standard-higher risk of PE and current contraindication for therapeutic anticoagulation. Because the etiology and acuity of the ICH were not clear, the plan was for a repeat brain MRI and serial noncontrast brain CT to inform the initiation of prophylactic-dose anticoagulation. MRI with and without contrast revealed increased nodular left frontal enhancement, concerning for progressive glioblastoma. CT brain obtained at 72 hours demonstrated stable and resolving ICH. At this stage, prophylactic-dose enoxaparin was started (40 mg once daily). Surveillance CT brain 48 hours later was stable. Her neurological symptoms were improving, and there were no PE symptoms or change in her right leg pain and edema. She was discharged home on enoxaparin 40 mg once daily, with outpatient neurology and hematology follow-up. Figure 3 shows our approach to the management of patients with brain cancer and acute VTE who experienced ICH within the previous 30 days.

Anticoagulation selection in patients with primary brain tumors

The retrospective cohort studies showing an increased ICH risk with anticoagulation (compared with no anticoagulation) in patients with high-grade glioma primarily included patients receiving LMWH. Initial reports from small retrospective cohort studies suggested safety of DOACs in comparison with LMWH in patients with primary brain cancer.59,68 A recent meta-analysis of 613 patients with primary brain cancer treated with either DOACs (n = 193) or LMWH (n = 420) revealed a statistically significant reduction in ICH incidence in DOAC-treated patients (RR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.18-0.69) compared with LMWH.20 Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in fatal ICH (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.11-1.34). Of note, the cumulative ICH incidence across all studies with DOACs was low at 5.1% (95% CI, 2.8-9.3), comparable to the 4.4% ICH incidence reported in patients with primary brain cancer not receiving anticoagulation.36 Reassuringly, all the individual studies in this meta-analysis showed the same trend toward less bleeding with DOACs.20 Nonetheless, because there was initial theoretical concern regarding increased ICH risk with DOACs in these patients, selection bias remains possible, potentially underestimating the risk of bleeding with DOACs. Taken together, we now consider DOACs as the preferred anticoagulant class in patients with primary brain cancer. LMWH remains a treatment option that may be still preferred in some scenarios such as thrombocytopenia and in the perioperative setting (Figure 1).

Initiation of anticoagulation in setting of ICH

Aside from arising from a high-risk malignancy (melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, glioblastoma, etc), there are no defining radiologic features that predict an intracranial tumor’s risk for hemorrhage. Preexisting intratumoral hemorrhage is generally considered a risk factor for recurrent hemorrhage, and some studies suggest that lesional hemorrhage before SRS increases the risk of post-SRS ICH, particularly among those receiving concurrent anticoagulation.23,24 Intraventricular and convexity tumor locations are associated with higher rates of spontaneous hemorrhage in meningiomas, but this finding has not been described for other tumor types. Association of ICH with total tumor volume or lesional features, such as internal necrosis, tumoral cyst, and peritumoral edema, has also not been consistently described in the literature. We previously analyzed the rates of recurrent ICH in patients with brain tumors after the reinitiation of anticoagulation. Among 38 patients with smaller bleeds (including hemosiderin deposits alone), only 1 patient with glioma developed recurrent ICH. Conversely, among the 16 patients with larger ICH (>10 mL) who restarted anticoagulation, there were 2 subsequent ICH (cumulative incidence of 14.5%).25 Accordingly, we generally use a conservative cutoff of 10 mL to define more serious tumor-associated ICH with a higher likelihood of expansion (Figure 3).

Data extrapolated from the spontaneous ICH literature suggest that prophylactic dosing of unfractionated heparin (or LMWH) can be safely administered within several days of ICH diagnosis. For instance, in a small randomized trial, the administration of unfractionated heparin (5000 units every 8 hours) starting at day 4 was not associated with an increase in hematoma expansion compared with thromboprophylaxis starting at day 10.69 Retrospective studies similarly demonstrated the safety of initiation of LMWH prophylaxis within 48 hours of admission.29,70 Accordingly, in patients with proximal VTE, we favor the placement of an IVC filter (when indicated) along with administration of prophylactic dosing of either unfractionated heparin or LMWH within 2 to 4 days after the diagnosis of ICH (Figure 3). In patients with larger ICH (≥10 mL) or multifocal lesions, all pharmacologic anticoagulation is typically held until stability demonstrated on repeat imaging and a discussion with neurology or neurosurgery. There is limited literature on the timing of reinitiation of therapeutic anticoagulation; based on studies in traumatic ICH, we are often hesitant to administer before 10 to 14 days and often longer in the setting of untreated brain tumors.71,72 In this context, we carefully consider the risks and benefits in terms of thrombosis embolization vs expansion of ICH.

When we consider the placement of IVC filters

Anticoagulation is often initially contraindicated in patients with brain cancer with acute/subacute ICH and concurrent acute PE or proximal lower extremity DVT. In this context, placement of a removable IVC filter may be considered; however, the evidence regarding the use of IVC filters in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis is limited.73,74 In a recent large population-based study, Balabhadra et al evaluated outcomes in patients with cancer who underwent IVC filter placement. They observed an improved PE-free survival rate among 33 740 patients with acute lower extremity DVT who underwent IVC filter placement compared with propensity score–matched cohort without IVC filter (hazard ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.64-0.75).75 In a subgroup analysis of patients with primary brain tumors in this cohort, there was a nonsignificant decrease in the recurrence rate of PE among patients with IVC filters in comparison with those without IVC filters (4.3% vs 5.6% [P = .2], respectively). In this study, IVC filter placement did not increase the risk of new DVT.75 A matched cohort analysis of patients with cancer with PE and/or lower extremity DVT enrolled in the RIETE Registry compared the rates of PE-related mortality between those with IVC filter placement due to contraindications for anticoagulation and those without IVC filters. Among the 247 patients with IVC filters (66% with no initial anticoagulation), there was a significantly lower PE-related mortality rate (0.8% vs 4%), a nonsignificantly lower risk of all-cause mortality, but a trend toward higher VTE recurrence rate than matched controls.76 Accordingly, we consider IVC filter placement in patients with brain cancer with acute PE (apart from isolated subsegmental PE) or proximal lower extremity DVT who experienced a recent ICH (Figure 3) and in selected patients without ICH who have a very high risk of anticoagulation-associated ICH (Figure 1).

Conclusions

How to approach the management of acute VTE in a patient with brain tumor remains challenging. The more straightforward decisions are in those patients with metastatic brain tumors considered lower risk for hemorrhage (eg, lung or breast cancer) without evidence of ICH and with a recent diagnosis of proximal DVT or central PE. In those instances, evidence suggests that the administration of therapeutic anticoagulation does not increase the risk of ICH (in the absence of additional bleeding risk factors). In many other settings, the decision is a difficult balance of managing bleeding risks and risk of recurrent or progressive VTE. If there is a high concern for hemorrhage, we favor reduced intensity anticoagulation and/or placement based off of an IVC filter in an attempt to mitigate immediate risks of proximal embolization of thrombus. We recognize the retrospective nature of the current data and call for additional quality research in this field. Among the many knowledge gaps is the need to develop better models to identify which patients are most likely to develop hemorrhagic complications with anticoagulants.

Acknowledging these uncertainties, it is imperative to have a careful and informed discussion of anticoagulation risks vs benefits with patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rekha Parameswaran (Department of Hematology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC]) and Igor Gavrilovic (Department of Neurology, MSKCC) for their involvement in developing the MSKCC Clinical Guidelines for VTE Management in Brain Tumor Patients. The authors also thank Adam Kahleifeh and Edward Lee (Department of Neurology, MSKCC) for their critical review of evidence-based data for anticoagulation selection in patients with primary and secondary brain tumors.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant NCI P30 CA008748.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed to conception/design, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.L. reports honorarium from LEO Pharma. J.I.Z. reports consultancy for Calyx, Incyte, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Regeneron; and serving on data monitoring boards for Sanofi and CSL Behring. J.A.W. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey I. Zwicker, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; email: zwickerj@mskcc.org.

References

Author notes

A.L. and J.A.W. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal