Abstract

A 64-year-old woman with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) characterized by a pathological variant in ACVRL1 presents to the clinic for follow-up. Manifestations of HHT include frequent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding, leading to iron-deficiency anemia. Bevacizumab is initiated, with resolution of the anemia. While maintained on a regimen of bevacizumab every 6 weeks, she continues to report frequent epistaxis and has ongoing iron-deficiency requiring periodic iron infusions. She also finds the bevacizumab infusions inconvenient. She is interested in discussing other options for managing her disease.

Learning Objectives

Appreciate that HHT is a bleeding disorder caused by impairment in the regulation of angiogenesis

Become familiar with the systemic antiangiogenic therapies used in HHT management

CLINICAL CASE

A 64-year-old woman with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) characterized by a pathologic variant in ACVRL1 presents to clinic for follow-up. Manifestations of HHT include frequent epistaxis and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding leading to iron deficiency anemia. Bevacizumab was initiated, with a resolution of the anemia. While maintained on a regimen of bevacizumab every 6 weeks, she continues to report frequent epistaxis and has ongoing iron deficiency requiring periodic iron infusions. She also finds the bevacizumab infusions inconvenient. She is interested in discussing other options for managing her disease.

Biology of HHT and its clinical manifestations

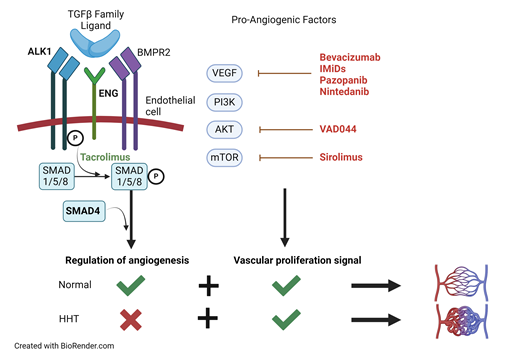

HHT is a disease of disordered angiogenesis, with its cardinal manifestation being mucocutaneous bleeding.1 HHT is the second most prevalent inherited bleeding disorder, affecting 1 in 5000 people worldwide.2 More than 700 causative mutations involving impairment in the TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway have been identified, leading to a loss of normal regulatory control of angiogenesis.3,4 As a result, affected individuals have a predisposition for arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) or focal abnormal connections between arteries and veins. The development of AVMs in a particular vascular bed is thought to require a “second hit” from injury, inflammation, or acquisition of a somatic mutation.5 TGF-β/BMP signaling is also important for maintaining the extracellular matrix supporting the vasculature, and the loss of this support leads to weakened vessels that are prone to bleeding.6

Over 95% of individuals with HHT have heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in genes encoding the TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway receptors endoglin (ENG) and activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK-1/ACVRL1), which are predominantly expressed on endothelial cells.7 Around 2% of individuals have mutations in the downstream transcription factor SMAD4.5 Mutations in GDF2/BMP9, a member of the TGF-β ligand superfamily, lead to a vascular anomaly syndrome with HHT-like features.8

As a vascular disease, HHT can affect multiple organ systems. Small mucocutaneous AVMs, known as telangiectasias, are visible as dilated veins over the fingers, lips, tongue, and earlobes. Telangiectasias within the nose lead to frequent and often debilitating epistaxis. GI bleeding may occur as a consequence of intestinal AVMs.9 The consequence of recurrent epistaxis and/or GI bleeding is the development of iron deficiency anemia, the prevalence of which is estimated to be 50%.10 Cerebral AVMs are the most feared complication of the disease and may lead to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.9 The consequences of HHT are not limited to bleeding, however. AVMs in the pulmonary vasculature may cause right-to-left shunting, chronic hypoxemia, and rarely ischemic stroke or cerebral abscess from paradoxical embolization.9 Shunting between hepatic arteries and veins bypasses the hepatic circulation and can lead to decreased systemic vascular resistance and high-output heart failure.11 Individuals with SMAD4 mutations are predisposed to developing juvenile polyposis syndrome and an associated increased risk of GI cancer.12

Antiangiogenic therapies in HHT

Until recently, treatment options for HHT were limited to local/topical therapies for epistaxis and antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid. The advent of antiangiogenic therapy for HHT in the late 2000s has revolutionized the management of affected patients.13,14 Evidence for the use of angiogenesis inhibitors in HHT is apparent from studies of ENG+/− and ALK1+/− mouse models that develop focal HHT-like lesions. These mice show alterations in the expression of angiogenesis regulators that resolve with antiangiogenic therapy along with improvement in vascular dysplasia.1,15-18 Reflecting improved understanding of the biology of the disease, each of the emerging therapies discussed below targets angiogenesis in some manner (Table 1).

Key clinical trials of systemic antiangiogenic therapies for the management of HHT

| Drug . | Trial . | Type . | n . | Status or major findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous bevacizumab | ||||

| NCT04404881 | Single-arm trial | 33 | Recruiting | |

| Dupuis-Girod19 | RCT | 24 | ↔ Transfusion and ↑Hgb, QOL | |

| Al-Samkari20 | Retrospective | 238 | ↓ESS, transfusion and ↑Hgb | |

| Vazquez27 | Retrospective | 20 | ↑Hgb and ↓transfusion | |

| Al-Samkari28 | Retrospective | 13 | ↓Transfusion, epistaxis and ↑Hgb | |

| Guilhem29 | Retrospective | 46 | Clinical improvement in 74% | |

| Iyer30 | Retrospective | 34 | ↓ESS, transfusion | |

| Dupuis-Girod21 | Single-arm trial | 25 | ↓Cardiac index, epistaxis, and ↑QOL | |

| Pazopanib | ||||

| NCT03850964 | RCT | 70 | Recruiting | |

| Parambil24 | Retrospective | 13 | ↓Transfusion, ESS and ↑Hgb | |

| Faughnan31 | Single-arm trial | 7 | ↓Epistaxis and ↑Hgb, QOL | |

| Pomalidomide | ||||

| Al-Samkari23 | RCT | 144 | ↓ESS and ↑QOL | |

| Thalidomide | ||||

| Invernizzi32 | Single-arm trial | 31 | ↓ESS, transfusion and ↑Hgb | |

| Tacrolimus | ||||

| NCT04646356 | Single-arm trial | 30 | Active not recruiting | |

| Alvarez-Hernandez26 | Single-arm trial | 11 | ↓ESS and ↑Hgb | |

| Nintedanib | ||||

| NCT04976036 | RCT | 48 | Recruiting | |

| NCT03954782 | RCT | 61 | Completed | |

| VAD044 | ||||

| NCT05406362 | RCT | 80 | Recruiting | |

| Sirolimus | ||||

| NCT05269849 | Single-arm trial | 10 | Recruiting |

| Drug . | Trial . | Type . | n . | Status or major findings . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous bevacizumab | ||||

| NCT04404881 | Single-arm trial | 33 | Recruiting | |

| Dupuis-Girod19 | RCT | 24 | ↔ Transfusion and ↑Hgb, QOL | |

| Al-Samkari20 | Retrospective | 238 | ↓ESS, transfusion and ↑Hgb | |

| Vazquez27 | Retrospective | 20 | ↑Hgb and ↓transfusion | |

| Al-Samkari28 | Retrospective | 13 | ↓Transfusion, epistaxis and ↑Hgb | |

| Guilhem29 | Retrospective | 46 | Clinical improvement in 74% | |

| Iyer30 | Retrospective | 34 | ↓ESS, transfusion | |

| Dupuis-Girod21 | Single-arm trial | 25 | ↓Cardiac index, epistaxis, and ↑QOL | |

| Pazopanib | ||||

| NCT03850964 | RCT | 70 | Recruiting | |

| Parambil24 | Retrospective | 13 | ↓Transfusion, ESS and ↑Hgb | |

| Faughnan31 | Single-arm trial | 7 | ↓Epistaxis and ↑Hgb, QOL | |

| Pomalidomide | ||||

| Al-Samkari23 | RCT | 144 | ↓ESS and ↑QOL | |

| Thalidomide | ||||

| Invernizzi32 | Single-arm trial | 31 | ↓ESS, transfusion and ↑Hgb | |

| Tacrolimus | ||||

| NCT04646356 | Single-arm trial | 30 | Active not recruiting | |

| Alvarez-Hernandez26 | Single-arm trial | 11 | ↓ESS and ↑Hgb | |

| Nintedanib | ||||

| NCT04976036 | RCT | 48 | Recruiting | |

| NCT03954782 | RCT | 61 | Completed | |

| VAD044 | ||||

| NCT05406362 | RCT | 80 | Recruiting | |

| Sirolimus | ||||

| NCT05269849 | Single-arm trial | 10 | Recruiting |

ESS, epistaxis severity score; Hgb, hemoglobin, transfusion, red blood cell transfusion; QOL, quality of life; RCT, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial.

Intravenous bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against the proangiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), has become widely used for the management of HHT. A recently published randomized controlled trial of transfusion-dependent HHT patients found that more bevacizumab-treated patients were able to halve their transfusion need compared with those treated with placebo (63.6% vs 33.3%).19 The primary outcome did not meet statistical significance; however, only 12 patients were enrolled in each arm, and there were significant improvements in important secondary outcomes such as mean hemoglobin and quality-of-life scores. InHIBIT-Bleed was a retrospective study of 238 patients across 12 HHT centers that reported significant improvements in anemia, epistaxis severity score, transfusions, and iron dependence on bevacizumab compared with pretreatment baseline.20 The potential benefits of bevacizumab are not limited to the control of bleeding. In a phase 2 trial of bevacizumab in patients with severe hepatic AVMs and high cardiac output, 20 out of 24 patients treated with bevacizumab for 2.5 months achieved improvement in cardiac index in addition to significant improvements in epistaxis and quality of life.21 The most common adverse events (AEs) associated with bevacizumab include hypertension and proteinuria. While increased thromboembolic events have been observed in patients treated with bevacizumab for other indications, such as malignancy, trials in HHT have not demonstrated increased thrombotic risk.20

Thalidomide was the first of a class of immunomodulatory imide drugs that inhibit signaling via proangiogenic factors such as VEGF, hypoxia inducible factor 1α, and platelet derived growth factor. A systematic review investigating thalidomide in HHT found significant increases in hemoglobin and reductions in epistaxis frequency and duration and transfusion dependence on therapy.22 In the studies that reported AEs, 17.5% of patients had to discontinue therapy due to AEs, with GI distress being the most common. Pomalidomide, a newer and more potent antiangiogenic agent with a more favorable AE profile, was recently evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (PATH-HHT).23 Participants in the study treated with pomalidomide experienced a significant reduction in the epistaxis severity score of −1.84 (95% CI, −2.24, −1.44) at 12 weeks and significant improvement in quality of life scores at 6 months.23

Pazopanib (Paz) is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the VEGF receptor along with receptors for other proangiogenic growth factors. A recent series investigated Paz in 13 transfusion- dependent patients, all of whom achieved transfusion independence on therapy with significant improvement in epistaxis severity scores by an average of −4.77 (−3.11, −6.44).24 AEs associated with Paz, including hypertension, lymphocytopenia, and fatigue, are dose dependent. Importantly, the median dose of Paz required for efficacy in HHT was one-eighth the typical starting dose for oncologic indications in this study. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of low-dose Paz (NCT 03850964) is currently open for recruitment.

A handful of potential antiangiogenic therapies for HHT are under investigation (Table 1). Two clinical trials of nintedanib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks VEGF signaling, have been registered (NCT04976036 and NCT03954782). Therapies targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which is involved in the upregulation of angiogenic factors such as VEGF, are under investigation.25 Clinical trials of VAD044, an AKT inhibitor (NCT05406362), and sirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor (NCT05269849), are also underway. Additionally, there is emerging evidence for the use of tacrolimus, a promoter of SMAD phosphorylation downstream of the TGFβ receptor, in HHT.26

Conclusion

Recent decades have seen enormous advances in our understanding of the genetic and mechanistic underpinnings of HHT, as well as several encouraging clinical trials of systemic antiangiogenic agents. For the patient case introduced above, enrollment in a clinical trial of an agent such as VAD044 or Paz should be offered. If trials are not available to the patient, high-quality evidence from the PATH-HHT randomized controlled trial would support pomalidomide as an effective and convenient oral option. An off-label use of Paz would be reasonable as an alternative. As more promising therapies are investigated, a need arises for head-to-head comparisons to guide a new standard of care for the disease. Above all, regulatory approvals are needed to ensure these advances are accessible to patients.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Harish Eswaran: no competing financial interests to declare.

Raj S. Kasthuri: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Harish Eswaran: Off-label use of medications is discussed in this article.

Raj S. Kasthuri: Off-label use of medications is discussed in this article.