Abstract

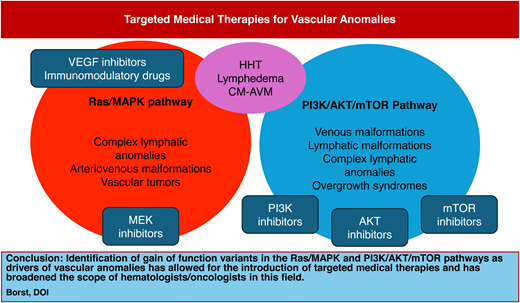

The last 2 decades of genetic discovery in the field of vascular anomalies have brought targeted medical therapies to the forefront of care patients with vascular anomalies and have broadened the role of hematologists/oncologists in this field. Many vascular anomalies have now been identified to be driven by somatic gain-of-function variants in the PI3K/AKT/ mTOR and Ras/MAPK intracellular signaling pathways. This has led to the introduction of various antiangiogenic agents that inhibit these pathways. Knowledge of the indications for and the safe administration of these agents in patients with vascular anomalies is now a crucial part of training for hematologists/oncologists.

Learning Objectives

Review the available targeted medical therapies for vascular anomalies

Introduce basic guidelines for dosing and monitoring patients with vascular anomalies on targeted medical therapies

Introduce future therapies being evaluated for vascular anomalies

CLINICAL CASE

A 9-year-old boy with a history of a port-wine stain of his right lower extremity presents to your clinic for evaluation due to a new increase in leg size and pain (Figure 1). His parents report that he was born with a large red mark on his right lateral thigh that was initially called a hemangioma. When it did not resolve over the first year of life, the diagnosis was changed to a port-wine stain. The lesion has grown with him. He occasionally has some small blebs within the red area that bleed and crust over but has otherwise had no significant symptoms related to the birthmark. However, in the past few years they have noticed that his right leg seems to be somewhat larger than the left, and in the last few months he has had intermittent complaints of pain in the leg. They said that the pain seems to be worse when he is very active or standing for long periods of time. He has some improvement with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and rest. However, they are concerned that this is starting to interfere with activities, and he recently asked to quit his soccer team due to pain. On exam, you note that the right lower extremity has an increased circumference and length compared to the left. He has some distended superficial veins throughout the leg and skin notable for a geometric erythematous capillary malformation with some overlying lymphatic blebs. Laboratory studies indicate a normal complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen level but a markedly elevated D-dimer at 7.86 ug/mL fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU; range < 0.5). You explain to the family that his presentation is that of a capillary-venous-lymphatic malformation with overgrowth, sometimes referred to as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. The family asks about the next steps in evaluation and options for management.

Patient clinical photographs and baseline laboratory studies. Photographs demonstrate a child with a capillary-venous- lymphatic malformation of the right lower extremity with overgrowth. Symptoms include pain, fatigue, and exercise intolerance. Laboratory studies were notable for an elevated D-dimer without any other hematologic abnormalities. Hgb, hemoglobin; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial prothrombin time; WBC, white blood cell count.

Patient clinical photographs and baseline laboratory studies. Photographs demonstrate a child with a capillary-venous- lymphatic malformation of the right lower extremity with overgrowth. Symptoms include pain, fatigue, and exercise intolerance. Laboratory studies were notable for an elevated D-dimer without any other hematologic abnormalities. Hgb, hemoglobin; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial prothrombin time; WBC, white blood cell count.

Introduction

Rapid advances in the molecular knowledge of vascular anomalies in the last decade have dramatically changed the landscape of medical therapies available to patients. Prior to a more detailed understanding of the pathophysiology of these disorders, most treatment centered around surgical and procedural interventions. Knowledge of the genotype associated with known clinical phenotypes (Figure 2) has allowed clinicians to more accurately classify vascular lesions and to adapt oncologic medications to control symptoms and other complications. This has also allowed patients to avoid risky surgical interventions and provided treatment options to some patients who previously had none.

Genetic pathways involved in vascular anomalies and targeted therapeutics. This diagram depicts the known association of various vascular anomalies with genetic variants in the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Highlighted in red are the various targeted medical therapies currently in use for these disorders.

Genetic pathways involved in vascular anomalies and targeted therapeutics. This diagram depicts the known association of various vascular anomalies with genetic variants in the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Highlighted in red are the various targeted medical therapies currently in use for these disorders.

Hematologists/oncologists have long been involved with supportive care and antithrombotic management in vascular malformations, as well as broad-based chemotherapeutic approaches to vascular tumors.1 However, the introduction of mTOR inhibition for vascular anomalies in the early 2000s dramatically changed the approach to management of many of these entities and brought hematologists/oncologists to the forefront of this field. Hematologists/oncologists now hold a central role in the multidisciplinary vascular anomalies team, providing long-term targeted medical therapies (Table 1) as well as serving as a medical home for this rare disease population.1

Targeted medical therapies currently in use for vascular anomalies

| Drug . | Class . | Clinical uses . | Typical dosing . | Key adverse effects . | Typical monitoringa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus | mTOR inhibitor | Vascular malformations and tumors, complex lymphatic anomalies (CLAs) | 0.8 mg/m2 twice daily in children, once daily dosing in adults or older teens, ~2 mg/d Topical formulation also available for cutaneous lesions | Mucositis, headaches, rash, nausea, abdominal pain, anemia, immunosuppression, lymphopenia, hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia Rare: hypersensitivity pneumonitis, lymphedema, secondary malignancy related to immunosuppression | Every 1-3 mo with labs (CBC/diff, CMP, lipid panel, sirolimus trough, +/− D-dimer, and fibrinogen if pertinent) and physical examination |

| Alpelisib | PI3Kα inhibitor | PROS, lymphatic malformations, venous malformations, CLAs | 50-125 mg once daily in children, 125-250 mg once daily in adults | Hyperglycemia, mucositis, headaches, nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, rash, alopecia, mood disturbance | Every 1-3 mo with labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos, hemoglobin A1C, +/− D-dimer, and fibrinogen if pertinent) and physical examination |

| Trametinib Selumetinib Cobimetinib | MEK 1/2 inhibitors | Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs, CLAs) | 0.0125 and 0.025 mg/ kg/d with dosing ranging from 0.5 mg-1 mg/d for older children and adults | Rash, paronychia, diarrhea, edema, bleeding, thrombosis, alopecia, ocular toxicity (retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion), cardiac toxicity (ventricular systolic dysfunction, arrhythmia, hypertension), colitis, pneumonitis, elevated creatinine phosphokinase | Every 1-3 mo with labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos, CK, lipase, +/− D-dimer, and fibrinogen if pertinent) and physical examination |

| Miransertib VAD044 | Pan-AKT inhibitor Allosteric AKT inhibitor | Proteus syndrome and PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum disorders. Phase 1 trial in HHT in progress. | 5 mg/m2/d (or 5-60 mg/d) | Dry mouth, stomatitis, headache, nausea, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia | Clinical trial monitoring was every 1-8 wk monitoring of physical examination, labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos, uric acid), urinalysis, and ECG51 |

| Bevacizumab | VEGF receptor inhibitor | Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), case reports in CNS and non-CNS AVMs | 5 mg/kg every 2 wk ( × 4-6 doses) then 5 mg/kg every 4-12 wk as maintenance55 | Hypertension, fatigue, proteinuria, thrombosis, headache, arthralgia, bone marrow suppression | CBC/diff, CMP, urinalysis, and careful physical examination with blood pressure evaluation at each infusion |

| Propranolol Atenolol | Nonselective β-adrenergic-blocker Selective β1-adrenergic-blocker | Infantile hemangiomas | 0.5-3/mg/kg/d generally taken twice a day | Hypotension, bradycardia, hypoglycemia, acral cyanosis, sleep disturbance | Monitor HR and BP at 1 and 2 h after initial dose and with significant dose increase, monitor glucose if clinical concerns, thyroid function testing if diffuse hepatic involvement, every 1-3 mo physical examination (and US if pertinent). Typical weaning starts around 12 mo but case dependent. |

| Thalidomide Lenalidomide Pomalidomide | Immunomodulatory drugs | Case reports in HHT and CNS and non-CNS AVMs | Variable, depending on clinical scenario. Thalidomide dosing reported between 50 mg twice weekly to 200 mg/d. Lenalidomide reported between 5 and 15 mg once daily. Pomalidomide dosing in the PATH-HHT trial was 4 mg once daily. | Neutropenia, dizziness, dry mouth, paresthesia, asthenia, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, rash, venous thrombosis | Monthly labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos), physical examination, and surveys required as part of REMS program.71 |

| Drug . | Class . | Clinical uses . | Typical dosing . | Key adverse effects . | Typical monitoringa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus | mTOR inhibitor | Vascular malformations and tumors, complex lymphatic anomalies (CLAs) | 0.8 mg/m2 twice daily in children, once daily dosing in adults or older teens, ~2 mg/d Topical formulation also available for cutaneous lesions | Mucositis, headaches, rash, nausea, abdominal pain, anemia, immunosuppression, lymphopenia, hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia Rare: hypersensitivity pneumonitis, lymphedema, secondary malignancy related to immunosuppression | Every 1-3 mo with labs (CBC/diff, CMP, lipid panel, sirolimus trough, +/− D-dimer, and fibrinogen if pertinent) and physical examination |

| Alpelisib | PI3Kα inhibitor | PROS, lymphatic malformations, venous malformations, CLAs | 50-125 mg once daily in children, 125-250 mg once daily in adults | Hyperglycemia, mucositis, headaches, nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, rash, alopecia, mood disturbance | Every 1-3 mo with labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos, hemoglobin A1C, +/− D-dimer, and fibrinogen if pertinent) and physical examination |

| Trametinib Selumetinib Cobimetinib | MEK 1/2 inhibitors | Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs, CLAs) | 0.0125 and 0.025 mg/ kg/d with dosing ranging from 0.5 mg-1 mg/d for older children and adults | Rash, paronychia, diarrhea, edema, bleeding, thrombosis, alopecia, ocular toxicity (retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion), cardiac toxicity (ventricular systolic dysfunction, arrhythmia, hypertension), colitis, pneumonitis, elevated creatinine phosphokinase | Every 1-3 mo with labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos, CK, lipase, +/− D-dimer, and fibrinogen if pertinent) and physical examination |

| Miransertib VAD044 | Pan-AKT inhibitor Allosteric AKT inhibitor | Proteus syndrome and PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum disorders. Phase 1 trial in HHT in progress. | 5 mg/m2/d (or 5-60 mg/d) | Dry mouth, stomatitis, headache, nausea, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia | Clinical trial monitoring was every 1-8 wk monitoring of physical examination, labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos, uric acid), urinalysis, and ECG51 |

| Bevacizumab | VEGF receptor inhibitor | Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), case reports in CNS and non-CNS AVMs | 5 mg/kg every 2 wk ( × 4-6 doses) then 5 mg/kg every 4-12 wk as maintenance55 | Hypertension, fatigue, proteinuria, thrombosis, headache, arthralgia, bone marrow suppression | CBC/diff, CMP, urinalysis, and careful physical examination with blood pressure evaluation at each infusion |

| Propranolol Atenolol | Nonselective β-adrenergic-blocker Selective β1-adrenergic-blocker | Infantile hemangiomas | 0.5-3/mg/kg/d generally taken twice a day | Hypotension, bradycardia, hypoglycemia, acral cyanosis, sleep disturbance | Monitor HR and BP at 1 and 2 h after initial dose and with significant dose increase, monitor glucose if clinical concerns, thyroid function testing if diffuse hepatic involvement, every 1-3 mo physical examination (and US if pertinent). Typical weaning starts around 12 mo but case dependent. |

| Thalidomide Lenalidomide Pomalidomide | Immunomodulatory drugs | Case reports in HHT and CNS and non-CNS AVMs | Variable, depending on clinical scenario. Thalidomide dosing reported between 50 mg twice weekly to 200 mg/d. Lenalidomide reported between 5 and 15 mg once daily. Pomalidomide dosing in the PATH-HHT trial was 4 mg once daily. | Neutropenia, dizziness, dry mouth, paresthesia, asthenia, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, rash, venous thrombosis | Monthly labs (CBC/diff, CMP, Mg, Phos), physical examination, and surveys required as part of REMS program.71 |

Standard at our center, but may vary by institution.

BP, blood pressure; CBC, complete blood count; CK, creatine kinase; CMP, complete metabolic panel; CNS, central nervous system; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; Mg, magnesium; Phos, phosphorus; REMS, risk evaluation and mitigation strategies; US, ultrasound.

Targeted medical therapies for vascular anomalies

mTOR inhibitors

Mechanism

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a major intracellular cell signaling pathway involved in numerous functions, including cell cycle regulation, proliferation, and migration. Many vascular anomalies have been shown to harbor gain-of-function variants in this pathway, which has led to the adoption of mTOR inhibition as an important target for medical management.2 Work in mouse models and cell culture studies has shown that mTORC2 inhibition by sirolimus results in the reduced activation of AKT and increasing levels of platelet-derived growth factor-β, which may reduce endothelial cell proliferation and migration.2,3 Prior work has also shown that everolimus has similar antiangiogenic properties, as evidenced by its use for angiomyolipomas in tuberous sclerosis.4,5

Clinical studies and efficacy

The first notable use of sirolimus for vascular anomalies was in a young infant with severe kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon who failed to respond to multiple other chemotherapeutic agents. In this child, and in several to follow, sirolimus induced rapid hematologic and clinical response within a matter of weeks and prompted additional evaluation in a prospective phase 2 study.1,6 This prospective trial demonstrated efficacy and safety in more than 80% of patients with vascular tumors and malformations and started a new era of targeted medical therapies in vascular anomalies.7 Several additional studies have confirmed sirolimus' efficacy since this time.8-10

The typical timing of initial response to sirolimus therapy is within 4 to 8 weeks of initiation. In venous malformations, sirolimus shows efficacy in decreasing pain and improving laboratory markers of intralesional coagulopathy. In lymphatic malformations, sirolimus can lead to the decreased size of cystic lesions, decreased fluid production, and improvement in pain. Overall, many patients report improvements in pain, functional limitations, and quality of life. A few key populations seem to have a decreased response to sirolimus, including patients with extensive venous malformations, those with significant lipomatous overgrowth, and patients with arteriovenous malformations.6,7,10

Dosing, monitoring, and adverse effects

Sirolimus is now used routinely in infants, children, and adults with vascular anomalies, particularly the slow-flow lymphatic and venous malformations. One case report has even demonstrated safe in utero use for a severe cervicofacial lymphatic malformation.11 While dosing regimens are individualized, the typical initial dosing is 2 mg/d for adults or 0.8 mg/m2 twice daily for children, with higher target trough levels for more severe disease and lower goals for long-term symptom control.1,2,7 While target trough levels vary by institution and by patient needs, typically higher targets are in the 8 to 15 ng/mL range with lower goals less than 8 ng/mL. Both tablet and liquid suspension are available. Close monitoring of levels in neonates and young infants is required given the differences in drug elimination.12 Topical sirolimus is also highly effective in some cutaneous manifestations of vascular anomalies, in particular cutaneous microcystic lymphatic malformations.13,14

Adverse effects seen with the long-term use of sirolimus include mucositis, headaches, gastrointestinal (GI) upset, hypertriglyceridemia, rash, headache, and cytopenias.7,8 While infectious complications due to immunosuppression remain a primary concern, real-world use in vascular anomalies suggests the risk for serious infections is low.15 Due to T-cell immunosuppression and variable lymphopenia, many groups give routine Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis with sirolimus therapy, in particular to young patients, those with lymphopenia, and those being treated with higher-dose therapy.16-18

PI3K inhibitors

Mechanism

PI3Ks are lipid kinases that play a crucial role in cell signaling, apoptosis, motility, and angiogenesis through the PI3K/AKT/ mTOR pathway. Gain-of-function variants in the PIK3CA gene, which encodes the p110α catalytic subunit, lead to aberrant activation of PI3K and are implicated in a large number of human cancers.19 This p110α subunit is a widely expressed isoform of PI3K, is expressed in endothelial cells, and is necessary for vascular development. In 2012, somatic variants in PIK3CA were identified in several vascular anomaly and overgrowth conditions now referred to as PROS (PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum).20,21 Initial work by a group in France demonstrated the efficacy of PI3Kα inhibition to decrease cellular proliferation in a mouse model of PROS.22

Clinical studies and efficacy

Alpelisib, a PI3K-α selective inhibitor, was first trialed in adults with solid cancers and ultimately approved in 2019 (as Piqray) as a breast cancer chemotherapeutic in combination with fulvestrant.23 Based on its efficacy in cancer and preclinical work in a PROS mouse model, this drug was first trialed on a compassionate-use basis in 2 patients with PROS, one with life-threatening symptoms that were ultimately reversed.22 Continued evaluation in a larger cohort of 17 patients showed similar success, and ultimately the drug was evaluated in a managed access program and currently in an ongoing phase 2 trial. The drug received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2022 (as Vijoice®) based on real-world retrospective data that is contingent on the prospective study. It is currently approved for patients aged 2 years and older with severe manifestations of PROS who require systemic therapy.24

In the EPIK-P1 retrospective observational study of patients with PROS who received alpelisib through a compassionate-use program, more than one-third of patients reached the primary end point of greater than or equal to a 20% reduction in target lesion volume. Importantly for this population, however, rates of improvement in other disease-related symptoms (fatigue, pain, limb asymmetry, and coagulopathy) were much more common, with more than 90% of patients experiencing a significant reduction in pain.25 Results are still pending from the EPIK-P2 study, but many clinical reports have touted impressive responses to alpelisib in patients with PROS as well as with isolated lymphatic malformations and extensive venous malformations due to TIE2/TEK variants.26-28

Dosing, monitoring, and adverse effects

Alpelisib dosing for vascular anomalies ranges from 50 mg/d to 250 mg/d. In the current EPIK-P2 trial, initial dosing for the pediatric cohort started at 50 mg, but a second dose level entry of 125 mg/d is being evaluated. Initial adult dosing is recommended at 125 mg/d, but many clinicians will utilize a lower starting dose depending on patient symptoms and preference. Although not immunosuppressive like sirolimus, alpelisib is associated with nausea, mucositis, headaches, and GI toxicity (diarrhea, increased stool frequency). Additionally, the major dose-limiting toxicity with alpelisib, especially in the adult population, has been hyperglycemia. This is due to PI3K-α inhibition leading to insulin resistance leading to decreased cellular glucose uptake and increased hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.22,29

MEK inhibitors

Mechanism

The identification of Ras/MAPK pathway variants in patients with arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and complex lymphatic anomalies (CLAs) in the last 5 to 7 years has opened up the targeting of this pathway as an option for patients with severe vascular anomalies.30-33 Work in mouse and zebra fish models of AVM and lymphatic disorders has shown that MEK inhibition can inhibit lesion progression and normalize mutated endothelial cells.34,35

Clinical studies

Several case reports have cited clinical improvement or stability with trametinib use in patients with AVMs who have not been responsive to embolization or surgery.36-38 Currently, trametinib and other MEK inhibitors are typically used in this clinical setting when patients have failed first-line procedural options. Whether the early initiation of these medications could prevent AVM progression is not known.38-40

For complex lymphatic anomalies, the first reported successful use of MEK inhibition was in kaposiform lymphangiomatosis, a rare lymphatic anomaly associated with significant lung involvement, coagulopathy, and a high mortality rate, now known to be caused by a pathogenic NRAS variant.31,41,42 MEK inhibitors have also been given with success to patients with complex conducting lymphatic disorders associated with germline Ras variants, such as the lymphatic anomalies seen in some children with Noonan syndrome, as well as isolated entities due to somatic Ras pathway variants.43-45 Recently, Ras pathway variants have also been described in Gorham Stout disease, and MEK inhibitors have been shown to stabilize severe bony osteolysis in Gorham Stout disease.46

Dosing, monitoring, and adverse effects

The optimal dosing of MEK inhibitors for AVMs and CLAs is not well-defined. However, in the pediatric setting most clinicians have adopted a starting dose of trametinib between 0.0125 and 0.025 mg/kg/d with dosing ranging from 0.5 to 1 mg/d for older children and adults.43,44,47 In 2023, trametinib was approved in combination with dabrafenib for low-grade gliomas with a BRAFV600 mutation requiring systemic therapy. This has allowed for expanded availability for pediatric patients, including use of the liquid formulation. MEK inhibitors are associated with a wide array of adverse effects, including gastrointestinal, skin, ophthalmologic, hematologic, and cardiovascular toxicity. Appropriate intervals for cardiac and ophthalmologic surveillance are not defined but should probably occur at least biannually.48

Other targeted agents

AKT inhibitor

Proteus syndrome is an overgrowth disorder, caused by somatic variants in the AKT gene, that is similar to PROS and frequently presents with vascular anomalies.49 Miransertib is an orally bioavailable pan-AKT inhibitor that has been demonstrated to have more potent antiproliferative activity than sirolimus.50 It has been demonstrated to have efficacy in patients with Proteus syndrome as well as in patients with CLOVES (congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi, scoliosis/skeletal and spinal anomalies), a subtype of PROS.51,52 Unfortunately, access to this drug remains fairly limited. Another AKT inhibitor, VAD044, showed successful inhibition of AVM formation in preclinical studies, and a phase 1b study is in progress for patients with HHT.53

Bevacizumab

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that acts as a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor, preventing the binding of VEGF to its receptor and thus having a broad and potent effect on angiogenesis.54 Within vascular anomalies, bevacizumab has primarily been used in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), where it has been shown to decrease the Epistaxis Severity Score and decrease transfusion requirements.40,55 While a few case reports exist utilizing bevacizumab in isolated extracranial AVMs, there has been no wide uptake of its use, probably owing both to efficacy and tolerability.56

Propranolol

Propranolol is a lipophilic nonselective β-adrenergic receptor blocker. Its use as an antivascular tumor agent was discovered serendipitously in the early 2000s, and it is now considered a first-line medical therapy for infantile hemangiomas requiring systemic treatment.57 Its mechanism of action is thought to be due to the non–β-blocker R+ enantiomer form of the drug. The R+ enantiomer results in SOX18 inhibition, which leads to vasoconstriction, the decreased release of nitric oxide, the blockade of other proangiogenic signals, and the induction of apoptosis.58,59 Atenolol, a hydrophilic, selective β1-adrenergic receptor blocker, has also been established as a safe and effective alternative to propranolol that has increased ease of dosing (once daily) and potentially fewer central nervous system effects.60 While often given for other vascular tumors, especially congenital hemangiomas and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, the efficacy of β-blockers in other vascular malformations and tumors is probably quite limited.61

Thalidomide derivatives

Thalidomide and its derivatives lenalidomide and pomalidomide are immunomodulatory drugs with potent antiangiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties that are used for many oncologic diagnoses.62 Mouse models of AVM have shown that these agents can increase platelet-derived growth factor-β expression within endothelial cells and thus mural cell coverage.63 A recent report demonstrated clinical success in a cohort of 18 patients with extensive extracranial AVMs unresponsive to procedural intervention or other medical therapies.64 This past year, results of the PATH-HHT trial demonstrated that pomalidomide reduced epistaxis and improved quality of life in people with HHT.65

Treatment considerations

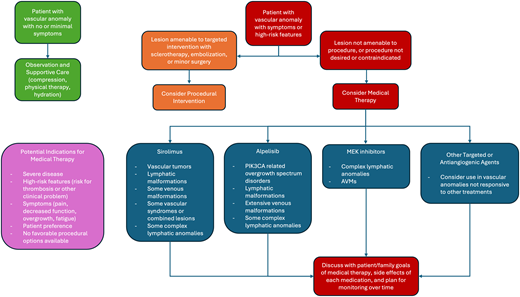

While a multimodal and multidisciplinary approach to the management of vascular anomalies is always critical, targeted medical therapies have dramatically changed the treatment landscape for people living with these disorders. As our options for these patients increase and improve, it remains important to keep in mind the goals of therapy. Unlike some malignant disorders in hematology/oncology, vascular malformations (and many vascular tumors) are generally treated with the intent of long-term control, rather than cure. This means that the decision to use medical therapies (and which ones) depends on very specific patient factors and requires significant patient/ physician discussion (Figure 3). For many patients with milder disease or minimal symptoms, observation alone with symptom control/prevention can be sufficient. This may mean compression garments, physical therapy, maintaining hydration and an active lifestyle, and ongoing patient education. For patients with more severe disease or those with high-risk features or who develop symptoms or complications, intervention should be considered. If a patient can be managed with a safe and effective interventional radiology procedure, this may be the first initial consideration. If this is not feasible or desired, or if particular symptoms dictate consideration of medical therapy, then a conversation about which drug options exist and the goals of therapy should ensue. Different from oncologic indications focused on disease cure, decisions about treatment initiation, goals, and duration of therapy are dictated by patient-specific goals. This is highly variable, depending on the vascular anomaly, but may include decreasing pain, improving stamina, decreasing extremity size, decreasing bleeding events, improving lung function, or increasing functionality. Whatever the goals of therapy, continuous close monitoring and reassessment are needed to ensure optimal outcomes and to consider additional treatment options as they arise. This is often best accomplished through a multidisciplinary vascular anomalies team, in which each team member/specialist can contribute their knowledge and expertise to the patient's ongoing care.

Treatment decision tree for patients with vascular anomalies. This decision tree outlines 1 approach to consideration of observation (green boxes), procedural intervention (orange boxes), or the use of targeted medical therapies (red boxes) for patients with vascular anomalies. In the purple box are outlined potential indications for medical therapies and in blue boxes are listed particular diagnoses most amenable to each therapeutic agent.

Treatment decision tree for patients with vascular anomalies. This decision tree outlines 1 approach to consideration of observation (green boxes), procedural intervention (orange boxes), or the use of targeted medical therapies (red boxes) for patients with vascular anomalies. In the purple box are outlined potential indications for medical therapies and in blue boxes are listed particular diagnoses most amenable to each therapeutic agent.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Due to worsening pain and a change in the function/ability to participate in activities, this patient is now a good candidate for a discussion about interventions. You consult with your colleague in Interventional Radiology, who does not think the patient is a good candidate for sclerotherapy at this time. You discuss options for medical therapy (Figure 3) with the patient and his family. The patient and his family elect to start medical therapy with sirolimus. He is initiated on standard dosing with a target trough of 6 to 10 ng/mL and has significant improvement in pain and function after 3 months of therapy. He has occasional oral ulcers but no other adverse effects. Around the age of 12 years, the patient takes an international flight to visit family and upon return he develops significant chest pain and shortness of breath. An examination in the emergency room reveals tachycardia and tachypnea. Baseline D-dimer on sirolimus therapy is 2.3 ug/mL FEU (range < 0.5) but has elevated to 10.9 ug/mL FEU (range < 0.5). Computed axial tomography of the chest reveals a right middle lobe segmental pulmonary embolus. Lower-extremity venous Doppler imaging reveals thrombosis within an ectatic popliteal vein in the right lower extremity. He is initiated on anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin and then transitions to rivaroxaban after 1 week of therapy. He completes 6 months of full-dose anticoagulation and subsequently undergoes marginal vein closure by Interventional Radiology. His family and physician make a shared decision to continue longer-term anticoagulation with prophylactic dosing, and this in combination with the sirolimus improves his pain. Around age 16 years, the patient begins to complain of increased heaviness in the right leg as well as worsening of the overgrowth, which is beginning to affect gait and exercise tolerance. He undergoes a punch biopsy of the cutaneous capillary malformation, and genetic testing reveals a pathogenic variant in PIK3CA c.1624G>A (p.Glu542Lys), which fits with the prior phenotypic diagnosis of capillary-venous-lymphatic with overgrowth. His family and physician rediscuss medical treatment options, and the patient is transitioned from sirolimus to alpelisib, with subsequent improvement in the size of his right lower extremity, pain, and function.

Looking ahead to the future

As we look to the future, many agents are currently being investigated for use in vascular anomalies (Table 2). This includes Tek receptor tyrosine kinase (TIE2 /TEK) inhibitors, of particular use for extensive venous malformations, and additional PI3K and MEK inhibitors for AVMs.66,67 Other active trials include evaluation of topical and percutaneous formulations of sirolimus and a recently halted trial of a topical PI3K inhibitor.68 Some alternative MEK inhibitors, mirdametinib and cobimetinib, are under investigation for fast-flow vascular anomalies, and 1 trial is investigating the presurgical use of trametinib in both intracranial and extracranial AVM. In the HHT world, 2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors, nintedanib and pazopanib, are being evaluated for their role in controlling epistaxis and anemia in HHT. The next decades are likely to bring additional trials and new agents. Combined with increased access to genetic testing and new methods for identifying somatic variants in this population, new therapeutic options for patients will likely become available. Hematologists/oncologists are uniquely equipped to support patients and families in the use of these medications, given our training in early-phase clinical trials, adverse effect monitoring, and the use of targeted agents and off-label therapies for malignancies.

Current and upcoming trials for targeted medical therapies in vascular anomalies

| Drug . | Current and upcoming trials . |

|---|---|

| Sirolimus | NCT04172922 (topical sirolimus for complicated vascular anomalies), NCT02638389 (VASE, European trial for complicated vascular anomalies refractory to standard care NCT03972592 (topical sirolimus for cutaneous lymphatic anomalies) NCT06160739 (Egyptian trial for lymphatic anomalies) NCT04921722 (percutaneous sirolimus in superficial vascular anomalies) NCT06239480, NCT05050149 (Qtorin 3.9% topical rapamycin for microcystic LMs) NCT05269849 (sirolimus for nosebleeds in HHT) |

| Alpelisib | NCT05948943 (EPIK-L1, alpelisib for LMs with PIK3CA variant) NCT04589650 (EPIK-P2, phase 2 alpelisib for PROS) |

| MEK inhibitors | NCT05983159 (TARGET-VM, evaluating mirdametinib in fast-flow vascular anomalies) NCT06098872 (trametinib for intracranial or extracranial AVMs prior to surgical intervention) NCT05125471 (cobimetinib for extracranial AVMs) |

| AKT inhibitors | NCT05406362 (safety and tolerability of VAD044 in HHT) NCT04980872 (safety and tolerability of miransertib in Proteus and PROS, not recruiting) NCT04316546 (change in cerebriform connective tissue nevus to miransertib in Proteus) |

| Bevacizumab | NCT06264531 (bevacizumab for symptomatic intracranial AVM) NCT04404881 (change in hematologic support score with bevacizumab in HHT) |

| Propranolol | NCT05479123 (impact of dose frequency of propranolol on sleep in infantile hemangiomas) |

| Thalidomide Lenalidomide Pomalidomide | NCT00389935 (thalidomide for GI AVMs) NCT01485224 (thalidomide for epistaxis and transfusion in HHT) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | NCT04976036 (nintedanib for epistaxis in HHT) NCT03850964, NCT03850730 (pazopanib for epistaxis duration and anemia in HHT) |

| Other | NCT06273111 (topical simvastatin for infantile hemangiomas) SAIPAN-trial (European trial, somatostatin analogues in HHT with GI bleeding) |

| Drug . | Current and upcoming trials . |

|---|---|

| Sirolimus | NCT04172922 (topical sirolimus for complicated vascular anomalies), NCT02638389 (VASE, European trial for complicated vascular anomalies refractory to standard care NCT03972592 (topical sirolimus for cutaneous lymphatic anomalies) NCT06160739 (Egyptian trial for lymphatic anomalies) NCT04921722 (percutaneous sirolimus in superficial vascular anomalies) NCT06239480, NCT05050149 (Qtorin 3.9% topical rapamycin for microcystic LMs) NCT05269849 (sirolimus for nosebleeds in HHT) |

| Alpelisib | NCT05948943 (EPIK-L1, alpelisib for LMs with PIK3CA variant) NCT04589650 (EPIK-P2, phase 2 alpelisib for PROS) |

| MEK inhibitors | NCT05983159 (TARGET-VM, evaluating mirdametinib in fast-flow vascular anomalies) NCT06098872 (trametinib for intracranial or extracranial AVMs prior to surgical intervention) NCT05125471 (cobimetinib for extracranial AVMs) |

| AKT inhibitors | NCT05406362 (safety and tolerability of VAD044 in HHT) NCT04980872 (safety and tolerability of miransertib in Proteus and PROS, not recruiting) NCT04316546 (change in cerebriform connective tissue nevus to miransertib in Proteus) |

| Bevacizumab | NCT06264531 (bevacizumab for symptomatic intracranial AVM) NCT04404881 (change in hematologic support score with bevacizumab in HHT) |

| Propranolol | NCT05479123 (impact of dose frequency of propranolol on sleep in infantile hemangiomas) |

| Thalidomide Lenalidomide Pomalidomide | NCT00389935 (thalidomide for GI AVMs) NCT01485224 (thalidomide for epistaxis and transfusion in HHT) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | NCT04976036 (nintedanib for epistaxis in HHT) NCT03850964, NCT03850730 (pazopanib for epistaxis duration and anemia in HHT) |

| Other | NCT06273111 (topical simvastatin for infantile hemangiomas) SAIPAN-trial (European trial, somatostatin analogues in HHT with GI bleeding) |

GI, gastrointestinal; LM, lymphatic malformation.

As the options for medical therapies expand for patients with vascular anomalies, it is critical that both patients and physicians keep in mind the goals of medical management in these disorders. Unlike most oncologic diagnoses, the goal in nearly all vascular anomalies is control, not cure. Similarly, the low variant allele frequency seen in most vascular anomalies means that frequently much lower doses are needed of these drugs compared to their use in cancer treatment. Successful endpoints for therapy do not include disease eradication but rather improvements in pain, coagulopathy, functionality, and quality of life. The development of a clear therapeutic plan between the patient and the physician is key to defining the goals and duration of therapy. Ongoing work on developing validated quality-of-life tools for people with vascular anomalies also helps to support clinical trial work in this growing field.69,70

Conclusion

The role of hematologists/oncologists in the field of vascular anomalies is growing due to advances in the understanding of disease-specific genotypes and the availability of targeted medical therapies adapted from oncology. These drugs can significantly improve quality of life and function for people with these disorders, and physicians with knowledge and awareness of these medical therapies are a crucial component of multidisciplinary care for vascular anomalies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Alexandra Borst: consultancy: Novartis.

Off-label drug use

Alexandra Borst: All drugs discussed in this manuscript are used off-label with the exception of alpelieisb as Vijoice and propranolol as Hemangeol for infantile hemangiomas.

Current affiliation

The current affiliation for Alexandra Borst is UNC Vascular Anomalies Program, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.