Abstract

This educational program outlines the importance of evolving clinical care models in response to increased life expectancy and variability in individual patient experiences, particularly in the context of sickle cell disease (SCD). It emphasizes the need for personalized and adaptive care models, in which the patient should play a central role, and the need for collaborative networks of physicians and caregivers, taking into account the multisystemic nature of the disease. The proposal also discusses the role of personalized medicine and technological advances, highlighting the need for a shared medical record; the balance between rare center expertise and widespread dissemination of knowledge; and the challenges in high- and low-income countries. It emphasizes the need to move toward personalized medicine, given the significant interindividual variability in both follow-up and treatment, and the introduction of more appropriate biomarkers and predictive algorithms to aid decision-making. The proposal includes real-world examples of successful adaptation in clinical care models. It concludes with a summary of the importance and benefits of evolving clinical care models and a future outlook on the evolution of clinical care in response to demographic changes. These proposals are intended to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state and future directions of clinical care models for SCD.

Learning Objectives

Understand how the disease's complexity and the diversity of patient experiences necessitate the continuous evolution of clinical care models.

Understand how the implementation of shared medical records, predictive algorithms, and appropriate biomarkers can facilitate clinical care.

Introduction

The importance of evolving clinical care models

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common genetic disorder and affects over 100 000 individuals in the United States,1 about 30 000 in France,2 and millions globally.3 Over time, the management of SCD has undergone a significant evolution, with scientific advancements leading to improved patient outcomes. Still, the necessity for significant advances in clinical care models is evident, especially for young adults with SCD who face distinctive challenges during their transition from pediatric to adult health care.4,5

Current statistics and trends in life expectancy and their impact on clinical care models

The life expectancy of individuals with SCD has increased over the years, with recent studies indicating an average life expectancy of approximately 52.6 years.6-8 This increase has shifted the burden of morbidity and mortality to the adolescent and adult periods, necessitating the development of care models that enable these individuals to improve both their quality of life and life expectancy, which remains 20 to 30 years below the general population in high-income countries.

Diversity of patient experiences

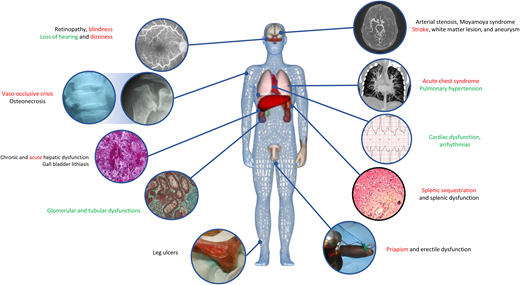

Patients with SCD experience a broad spectrum of complications (Figure 1) and encounter numerous barriers to receiving adequate health care.9,10 Economic obstacles (many patients live in distressed communities and lack insurance), transportation difficulties, and insufficient provider knowledge about acute crises and chronic organ complications can lead to disparities in health outcomes. These issues are particularly significant in the transfusion field.11 It is therefore crucial to understand these diverse experiences in order to develop effective and inclusive care models. Current models may be inadequate for patient follow-up for several reasons:

because they are structurally unsuitable (skills, technical facilities) or socially unsuitable (lack of health insurance);

because expert centers exist and are reimbursed but are inaccessible due to the distance separating them from the patient;

because the patient's problems require specialized multidisciplinary follow-up, and therefore good coordination, which does not exist;

because the problem is not currently covered by specific follow-up or treatment.

The need for personalized and adaptive care models

Given the complexity of SCD and the diversity of patient experiences, there is an urgent need for personalized and adaptive care models. These models should prioritize health equity, antiracism, and patient-centered multidisciplinary preventive care. They should also be flexible enough to meet the changing needs of patients as they transition from childhood to adulthood. These models must be adaptable to the patient's environment, including the local health care range of actions.

The multisystemic nature of SCD requires a collaborative, patient-centered approach to care

This includes the creation of networks of physicians and caregivers who can work together to provide comprehensive care. These networks can help address the multiple challenges faced by patients with SCD and improve their quality of life. These multidisciplinary approaches ensure a high level of expertise with regular knowledge updates. The multidisciplinary network must be accessible to all patients and all referring physicians, justifying the need for coordination tools and medical data sharing in accordance with legislation.

Personalized medicine and technological advances

The need for a shared medical record

CLINICAL CASE

A 23-year-old patient arrives at the emergency department (ED) with an acute chest syndrome (ACS). His condition deteriorated rapidly, and he was admitted to intensive care. His medical records did not mention any transfusion problems, and his antibody screening test was negative. A manual blood exchange transfusion was carried out. Four days later, the patient's clinical status deteriorated, and the patient presented with dark urine, a drop in hemoglobin, renal failure, and pulmonary hypertension. The diagnosis of delayed hemolysis transfusion reaction (DHTR) was made. Subsequent investigation revealed that a transfusion 4 years earlier at another hospital had been followed by a vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) and dark urine with a negative antibody screening test.

A shared medical record is crucial for the management of SCD. It enables smooth communication between different health care providers and ensures that all parties involved have access to the same information, even if they come from different centers with different patient record systems. This can significantly improve care coordination and reduce the risk of errors or miscommunication. In addition, a shared medical record can empower patients by giving them access to their own health information, encouraging engagement and self-management. For example, the risk of a DHTR, which alone accounts for 6% of mortality in France,12 makes it necessary to have at least 1 common transfusion record that can follow the patient, regardless of their whereabouts. In addition, a computerized platform for the collection of the patient's health data can be used for research purposes, with the patient's consent. However, the creation of these shared patient records faces many difficulties, among which restrictive regulations on medical data, protection against cyberattacks, interoperability issues with hospital information technology systems, and, often, the psychological blockage of caregivers for the use of such tools. Shared medical records should, if possible, be supported and funded at the state level. However, they can also be created by cell organizations or community organizations as long as they are accepted by a group of medical partners: DREPADOM13 for the management of vaso occlusive crisis (VOC) at home (Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris and Réseau Erythrocyte Drépanocytose) and Siclopedie® for patient follow-up (Réseau Erythrocyte Drépanocytose with the support of the Maladies Constitutionnelles du Globule Rouge health network).

Striking a balance between expertise from rare centers and broad dissemination, challenges in high- and low-income countries

A 35-year-old hemoglobin SS patient, who was asymptomatic during hydroxyurea therapy, experienced a ischemic stroke. He was placed under a blood exchange transfusion program by the center of excellence. The physician discussed the case via videoconference at the national neurological vascular multidisciplinary meeting. The neuroradiologist did not identify a vasculopathy to explain the stroke; therefore, anticoagulant therapy was initiated due to the left atrial dilatation to 58 mL/m2.14 The Holter electrocardiogram performed at the patient's home revealed rhythm disturbances, including transitions to atrial fibrillation, suggesting the need for continued long-term anticoagulation therapy. In the absence of other indications, blood transfusion exchange therapy was discontinued.

While a few centers often house the most advanced knowledge and expertise in SCD management, it is essential that this knowledge be widely disseminated to ensure that all patients, regardless of location or socioeconomic status, have access to quality care and essential medicine (eg, hydroxyurea). This requires the development of strategies for knowledge transfer and capacity building, particularly in low-income countries, where resources may be limited. Telemedicine, digital health technologies, social media, and other platforms (X, Doximity, VuMedi) can play a key role, enabling remote consultations and training. In this respect, the SARS-CoV2 pandemic has been a facilitating element in accelerating these approaches. Difficulties and variations in social insurance systems and cost recovery are also important limiting factors and require consideration of care pathways in their socioeconomic component. Multidisciplinary meetings, open at the national or international level, allow the most complicated patients to benefit from state-of-the-art expertise by facilitating interaction between the physician close to the patient and experts in the field. This allows access not only to the most relevant opinions for the most difficult cases but also to research protocols.

The necessity for a transition towards personalized medicine is imperative, given the significant interindividual variability observed in both follow-up and treatment

A 19-year-old boy is hospitalized for a third VOC in a year. He was transferred to the adult sector; his continuity of care was maintained because both the pediatric and adult centers were provided with efficient access to the patient's medical records. However, study of his social file revealed interruption of his financial aid to support his living expenses, and he was now working part-time to pay for his education. Additionally, he told the psychologist that he did not take hydroxyurea very well, indicating poor compliance. An increase of the dose, adapted to the area under the curve, was employed since the patient exhibited glomerular hyperfiltration. In addition, the social follow-up allowed him to regain his financial aid and prevented another hospitalization by allowing him to quit his part-time job.

SCD is characterized by significant interindividual and intraindividual variability, with patients experiencing a wide range of symptoms, complications, and responses to treatment. This variability is the result of both protective (eg, HbF, alpha thalassemic deletions) and aggravating (eg, membrane mutations, G6PD, APOL1) genetic factors,15-19 along with environmental factors such as climatic conditions,20 infectious agents, pollutants, and even daily stress (eg, economic, family, professional).21 This necessitates a transition toward personalized medicine, with appropriate treatment plans tailored to the individual. To achieve this, it is essential to adopt a global approach that integrates a comprehensive understanding of the disease in question, a psychological perspective, and a social approach. Particularly, the transition period presents numerous challenges, as the adult physician discovers the patient in a different perspective as the individual's family and economic environment undergoes profound changes. For this reason, it is crucial to ensure effective communication between the pediatric and adult centers, not only on the medical level, but also on the psychological and social fronts.

Application of personalized medicine

Improving treatment access and management

The application of personalized medicine can enhance the efficacy of treatment, minimize the occurrence of adverse effects, and facilitate patient satisfaction and acceptance of treatment (or compliance). This approach necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that influence disease progression and treatment response.

The therapeutic approach will be increasingly modulated. Even indications of hydroxyurea administration are frequently revised or questioned. Firstly, there is a global injustice in the access to hydroxyurea treatment for millions of patients,11 despite the fact that for the past 30 years,22,23 studies have shown its constant beneficial impact on mortality, including among children in Africa.24,25 As we better understand the issues affecting treatment compliance and the bioavailability of treatments,26–28 there is still much to discover. New therapeutic strategies are emerging, challenging us to identify the best therapeutic target, assess the benefit-risk balance, and evaluate the cost-benefit ratio. It is important to note that curative strategies have also improved, particularly in adults, with attenuated conditioning in bone marrow allografts with a better risk-benefit ratio, and soon access to gene therapy. However, due to its expected high cost, this will inevitably raise questions of patient selection.

The introduction of more appropriate biomarkers and predictive algorithms to support decision-making is a crucial step in the advancement of personalized medicine in SCD

During the SARS-CoV 2 pandemic, EDs were saturated with patients with COVID-19. Sickle cell patients with VOC were reluctant to come to the ED, and hospital beds were limited. Following the completion and analysis of the PRESEV score21 confirmation study, it was confirmed that the score exhibited an excellent negative predictive value for the absence of ACS in the follow-up of a VOC. This allowed us to quickly set up home care for VOC, with home nurses providing infusions, opioids, oxygen, and vital sign monitoring 2 or 3 times a day in coordination with the unit physician. This DREPADOM project is ongoing and has safely enrolled over 250 patients.

While robust clinical data are essential for the acceptance of a treatment, good care should aim to prevent rather than cure. This implies that there is a need to have very good surrogates to orient the risk before a serious event occurs. The first example is the acceleration of velocities on transcranial Doppler, which has been demonstrated to have an excellent association with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. This has allowed for the development of screening and adapted management strategies, including blood exchange transfusion, which have been shown to reduce the number of ischemic cerebral accidents.29 This approach should be extended to encompass all complications that have a significant impact on mortality or morbidity in SCD. It is necessary to consider the prediction of VOCs in the next year, the prediction of cardiopulmonary involvement by electrocardiogram ultrasound,30,31 the prediction of renal failure,32 and so on.

However, some surrogates remain imperfect due to their inadequate performance or the absence of a direct link with a pathophysiology that allows for the identification of different therapeutic strategies tailored to each individual. In order to be as relevant as possible, these imaging parameters or biomarkers must therefore have a comprehensible link with the pathophysiology. For instance, the concentration of hemoglobin alone is not a reliable criterion for improvement, as it fails to consider the level of intravascular hemolysis or the viscosity, which are major elements in the genesis of complications.33-35 Various biomarkers are currently being tested to predict vaso-occlusive events or organ damage (ie, plasma hemoglobin and haem, intracellular distribution of HbF and HbS, red blood cell elongation indices, point of sickling, and VCAM-1 adhesion assays). Connected devices could also be added to the set of diagnostic tools, as they could provide dynamic data on the patient's daily life that are otherwise lacking and could thus enrich the models by adding temporal and environmental information.

The advent of artificial intelligence represents a potential avenue for the integration of these diverse factors to develop predictive algorithms. Unsupervised approaches offer the opportunity to identify aspects of pathophysiology that may have been overlooked, either due to the quantity of data or the novelty of the subject matter.

Conclusion

The management of SCD has significantly evolved over time, resulting in enhanced patient outcomes and increased life expectancy. Nevertheless, the disease's complexity and the diversity of patient experiences necessitate the continuous evolution of clinical care models. These models must be personalized, adaptive, and capable of addressing the unique challenges faced by patients, particularly during their transition from pediatric to adult health care.

The advent of personalized medicine, bolstered by technological advances, offers promising avenues for improving the management of SCD. The implementation of shared medical records, predictive algorithms, and appropriate biomarkers can facilitate enhanced care coordination, patient engagement, and treatment efficacy. Furthermore, the establishment of collaborative networks of physicians and caregivers can ensure comprehensive and patient-centered care.

As we continue to navigate this path, it is crucial that health care providers and patients alike have a clear understanding of the functioning, capabilities, and risks associated with these new models. Prospective validation studies are essential for validating these new approaches, just as therapeutic protocols validate new medications. With concerted efforts and continued research, it is possible to envisage a future in which every patient with SCD, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status, has access to high-quality, personalized care.

Acknowledgment

Yanis Pelinski is acknowledged for the visual abstract, and Anne Laure Pham Hung d'Alexandry d'Orengiani is acknowledged for proofreading.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Pablo Bartolucci: cofunder of INNOVHEM.

Off-label drug use

Pablo Bartolucci: there is nothing to disclose.