Abstract

The aging obstetric population, combined with more frequent myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) diagnoses in younger patients, will result in hematologic providers increasingly caring for MPN patients in pregnancy. There are special considerations that pertain to management of pregnancy in MPN patients. This includes increased risks of thrombosis and hemorrhage as well as pregnancy complications that are likely related to placental dysfunction associated with an MPN diagnosis, including preeclampsia, preterm delivery, and intrauterine growth restriction. Complicating these outcomes is the uncertainty of the safety of many commonly used drugs in MPNs in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Given the overall low incidence of pregnancy in MPNs, many guidelines are based on expert opinions and extrapolation from other high-risk pregnancy populations. In this case-based review, we summarize the literature on MPN pregnancy outcomes and synthesize recommendations to provide guidance on the antepartum and postpartum management of MPN patients. Special attention is also made to issues relevant to preconception, including fertility and the use of assisted reproductive technology.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate pregnancy outcomes in MPN patients and risk factors for pregnancy complications

Synthesize evidence and expert opinions to formulate recommendations for preconception, antepartum, and postpartum management in MPNs

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), including essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and myelofibrosis (MF), are disorders of clonal hematopoiesis characterized by recurrent mutations in the driver genes JAK2, CALR, and MPL. Although typically diagnosed in the sixth decade, MPNs are increasingly seen in younger patients.1 Interesting data have emerged demonstrating that the acquisition of JAK2 driver mutations can occur decades before formal diagnosis,2 suggesting that MPNs are underdiagnosed in younger populations. As MPN diagnoses occur more frequently in younger patients and the obstetric population ages, management around preconception and pregnancy has become more relevant. This review presents a case-based discussion of management of MPN patients before, during, and after pregnancy, with a goal of providing guidelines for the preconception to postpartum period for women and families affected by an MPN.

CLINICAL CASE: BEFORE PREGNANCY

A 34-year-old woman presents with ET after she was found to have platelet count of 602 × 109/L on routine laboratory work. Mutational testing of peripheral blood revealed a JAK2 V617F mutation, and a bone marrow biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. She has never had a thrombotic event. She is currently on a combined estrogen-progesterone oral contraceptive pill but has been thinking of starting a family.

Hormonal contraception

Unlike in PV or MF, ET patients are more likely to be female and are diagnosed at younger ages.1 Most pregnancies in MPNs therefore occur in ET patients. In this particular case, the patient is considered low risk by the Revised International Prognostic Score of Thrombosis (R-IPSET), given her younger age and lack of thrombotic history.3 It is unclear how much estrogen-containing oral contraceptives increase baseline thrombotic risk in MPN patients, but, in the general population, they are associated with a 3- to 4-fold increase.4 Consistent with recommendations for other thrombophilias,5 avoiding estrogen-containing oral contraceptives is generally recommended in MPN patients, especially as many effective nonestrogen containing contraceptive options are available (ie, progestin-only pills; intrauterine devices, including the levonorgestrel intrauterine device Depo Provera; and the arm implant Nexplanon). As this patient has indicated interest in starting a family, a detailed obstetric history, including history of prior pregnancy losses and complications, should be taken. As this patient is low risk with a JAK2 mutation, it is appropriate to recommend a daily baby aspirin.

CLINICAL CASE (continued): BEFORE PREGNANCY

The patient switches to a progestin-only oral contraceptive pill and starts aspirin 81 mg daily. She is seen 2 years later, and at the visit she shares that she stopped all birth control and is trying to start a family. Her most recent platelet count remains stable. She has never been pregnant. She is considering her options and asks if she will need in vitro fertilization (IVF) because of her ET diagnosis.

MPN and fertility

It is unknown whether an MPN diagnosis impacts fertility. Only 1 retrospective study has evaluated childbirth patterns and rates; 1141 MPN patients were compared to age-matched controls.6 The childbirth rate was reduced by 22% in MPN women compared to controls, and at diagnosis, MPN women had significantly fewer children (1.29 vs 1.43). Subgroup analysis, however, showed similar childbirth rates between ET patients and controls, with decreased childbirth rates in MPN patients primarily driven by PV and MF patients.

These results raise the possibility that an MPN diagnosis impacts fertility, particularly in PV and MF, although we cannot determine if lower childbirth rates are due to women's decisions not to have children once diagnosed with an MPN. Cytoreductive agents also impact fertility, and this needs to be discussed in all reproductive-aged MPN patients, including men. Hydroxyurea, which is generally avoided during preconception given its teratogenicity, has been found to impact sperm motility in men7 and has possible effects on oocyte reserve in women with sickle cell disease.8 Supratherapeutic doses of pegylated interferons also have effects on fertility in animal studies.9 However, little is known about its impact on fertility in women at recommended treatment doses.

This patient can be given some reassurance that ET patients have similar rates of childbirth as healthy controls, although more studies are needed to validate these findings and ascertain risk factors for infertility in MPN patients. For now, guidelines for infertility management do not differ between MPN patients and the general population. In the absence of other etiologies of infertility, it is unknown how treatment of an underlying MPN impacts the probability of conception. However, certain considerations should be taken if the patient proceeds with any assisted reproductive technology (ART).

The risk of thrombosis is increased with in vitro fertilization (IVF), occurring in up to 0.3% of cycles, and this risk is particularly increased if patients develop ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.10 Antepartum risk of thrombosis in IVF pregnancies is double compared to non-IVF pregnancies, and the greatest risk of IVF-related thrombosis is in the first trimester of pregnancy. The American Society of Hematology guidelines on the management of venous thromboembolisms (VTEs) in pregnancy suggest against prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) in unselected patients undergoing an ART but note a lack of data to guide recommendations in those with other risk factors for thrombosis, such as an MPN.11 Some experts recommend prophylactic LMWH in addition to aspirin in MPN patients undergoing IVF, with the extension of anticoagulation prophylaxis through the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.12 Given the lack of evidence, however, these decisions should be discussed with the patient and individualized. Cytoreduction is not necessarily indicated for IVF, although it should be considered if certain risk factors are present (ie, concern for bleeding in a patient with extreme thrombocytosis and acquired von Willebrand disease undergoing oocyte retrieval).

CLINICAL CASE (continued): DURING PREGNANCY

At age 35 the patient becomes pregnant without ART and returns for follow up consultation; her platelet count is 703 × 109/L. She wishes to discuss management of her pregnancy.

Pregnancy outcomes in MPN patients

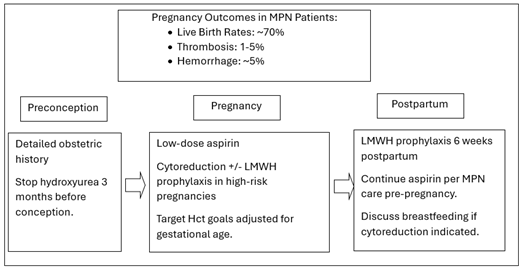

MPN patients who become pregnant generally have favorable outcomes (Table 1). Live birth rates (LBRs) in all MPN patients are estimated to be around 70%, which appears lower than the 80% LBRs seen in the general population.13 There has been 1 prospective study evaluating outcomes in pregnant MPN patients, with 58 women (56 singleton, 2 twin pregnancies) and 58 live births reported.14 LBRs for PV are lower than for ET,13 with a recent analysis of 129 PV pregnancies demonstrating an LBR of 68.7%.15 Outcomes of MF pregnancies are limited to case series. The largest study performed recently examined 24 MF pregnancies in 16 women (11 with prefibrotic and 5 with overt MF) and found an LBR of 71%.16

Summary of pregnancy outcomes in MPN patients within last 5 years

| Study . | No. of patients/ no. of pregnancies) . | MPN type (%) . | Treatments (%) . | Maternal/Fetal Complications (%) . | Live births (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elli et al. (2019)39 | 7/11 | PV (100) | ASA (91) IFN (18.2) LMWH (36) | Early pregnancy loss (9.1) Preterm (9.1) Stillbirth (18.2) | 81.8 |

| Gangat et al. (2020)25 | 61/102 | ET (90.1) PV (6.6) MF (3.3) | ASA (60) LMWH (9) IFN (15) | Hemorrhage (7) Thrombosis (4) Preeclampsia (4) Early pregnancy loss (31) Stillbirth (1) Preterm (2) IUGR (3) | 67 |

| Gangat et al. (2021)16 | 16/24 | MF (100) | ASA (58.3) LMWH (30) pIFN (8.3) | Hemorrhage (12.5) Thrombosis (0) Early pregnancy loss (20.8) Stillbirth (8.3) Preterm (8.3) IUGR (4.2) | 70.8 |

| How et al. (2020)23 | 52/121 | ET (100) | ASA (61.2) IFN (1.6) LMWH (31.7) | Hemorrhage (5.8) Thrombosis (2.5) Preeclampsia (3.3) Gestational HTN (0.8) Early pregnancy loss (32.2) Stillbirth (0.8) Preterm (7.4) IUGR (2.5) | 69 |

| İskender et al. (2021)30 | 21/21 | ET (100) | ASA (85.7) LMWH (66.7) pIFN (9.5) | Thrombosis (9.5) Preeclampsia (7.1) Early pregnancy loss (33.3) Stillbirth (0) Preterm (21.4) IUGR (14.3) | 66.7 |

| Landtblom et al. (2022)18 | 229/342 | ET (70) PV (11.8) MF (10.5) MPNU (8.7) | NA | Hemorrhage (14) Thrombosis (1) Preeclampsia, HELLP, gestational HTN (6) Preterm (12) Stillbirth (0.6) | NA |

| Lapoirie et al. (2020)40 | 14/27 | ET (64.3) PV (35.7) | ASA (67) LMWH (66.7) IFN (22) | Hemorrhage (11) Thrombosis (15) Early pregnancy loss (22.2) Stillbirth (4) Preterm (15) IUGR (15) | 70 |

| Maze et al. (2023)41 | 24/29 | ET (48) PV (31) MF (14) MPN NOS (7) | ASA (83) LMWH (17) IFN (17) Anagrelide (10) | Hemorrhage (3) Thrombosis (3) Preeclampsia (0) Early pregnancy loss (13.8) Stillbirth (4.2) | 83 |

| Schrickel et al. (2021)31 | 23/34 | ET (100) | ASA (58.8) LMWH (61.8) pIFN (58.8) IFN (41.2) | Hemorrhage (7.7) Thrombosis (0) Preeclampsia (4.2) Early pregnancy loss (26.5) | 73.5 |

| Wille et al. (2021)32 | 20/41 | PV (100) | ASA (56.1) LMWH (51.2) pIFN (7.3) IFN (7.3) | Hemorrhage (2.4) Thrombosis (2.4) Preeclampsia (2.4) Early pregnancy loss (44) Stillbirth (4.9) Preterm (7.3) | 51.2 |

| Wille et al. (2023)15 | 69/129 | PV (100) | ASA (48) LMWH (40) IFN (10.9) | Hemorrhage (15.5) Thrombosis (3.1) Preeclampsia (3.9) Early pregnancy loss (24.8) Stillbirth (7) Preterm (17.8) | 68.2 |

| Study . | No. of patients/ no. of pregnancies) . | MPN type (%) . | Treatments (%) . | Maternal/Fetal Complications (%) . | Live births (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elli et al. (2019)39 | 7/11 | PV (100) | ASA (91) IFN (18.2) LMWH (36) | Early pregnancy loss (9.1) Preterm (9.1) Stillbirth (18.2) | 81.8 |

| Gangat et al. (2020)25 | 61/102 | ET (90.1) PV (6.6) MF (3.3) | ASA (60) LMWH (9) IFN (15) | Hemorrhage (7) Thrombosis (4) Preeclampsia (4) Early pregnancy loss (31) Stillbirth (1) Preterm (2) IUGR (3) | 67 |

| Gangat et al. (2021)16 | 16/24 | MF (100) | ASA (58.3) LMWH (30) pIFN (8.3) | Hemorrhage (12.5) Thrombosis (0) Early pregnancy loss (20.8) Stillbirth (8.3) Preterm (8.3) IUGR (4.2) | 70.8 |

| How et al. (2020)23 | 52/121 | ET (100) | ASA (61.2) IFN (1.6) LMWH (31.7) | Hemorrhage (5.8) Thrombosis (2.5) Preeclampsia (3.3) Gestational HTN (0.8) Early pregnancy loss (32.2) Stillbirth (0.8) Preterm (7.4) IUGR (2.5) | 69 |

| İskender et al. (2021)30 | 21/21 | ET (100) | ASA (85.7) LMWH (66.7) pIFN (9.5) | Thrombosis (9.5) Preeclampsia (7.1) Early pregnancy loss (33.3) Stillbirth (0) Preterm (21.4) IUGR (14.3) | 66.7 |

| Landtblom et al. (2022)18 | 229/342 | ET (70) PV (11.8) MF (10.5) MPNU (8.7) | NA | Hemorrhage (14) Thrombosis (1) Preeclampsia, HELLP, gestational HTN (6) Preterm (12) Stillbirth (0.6) | NA |

| Lapoirie et al. (2020)40 | 14/27 | ET (64.3) PV (35.7) | ASA (67) LMWH (66.7) IFN (22) | Hemorrhage (11) Thrombosis (15) Early pregnancy loss (22.2) Stillbirth (4) Preterm (15) IUGR (15) | 70 |

| Maze et al. (2023)41 | 24/29 | ET (48) PV (31) MF (14) MPN NOS (7) | ASA (83) LMWH (17) IFN (17) Anagrelide (10) | Hemorrhage (3) Thrombosis (3) Preeclampsia (0) Early pregnancy loss (13.8) Stillbirth (4.2) | 83 |

| Schrickel et al. (2021)31 | 23/34 | ET (100) | ASA (58.8) LMWH (61.8) pIFN (58.8) IFN (41.2) | Hemorrhage (7.7) Thrombosis (0) Preeclampsia (4.2) Early pregnancy loss (26.5) | 73.5 |

| Wille et al. (2021)32 | 20/41 | PV (100) | ASA (56.1) LMWH (51.2) pIFN (7.3) IFN (7.3) | Hemorrhage (2.4) Thrombosis (2.4) Preeclampsia (2.4) Early pregnancy loss (44) Stillbirth (4.9) Preterm (7.3) | 51.2 |

| Wille et al. (2023)15 | 69/129 | PV (100) | ASA (48) LMWH (40) IFN (10.9) | Hemorrhage (15.5) Thrombosis (3.1) Preeclampsia (3.9) Early pregnancy loss (24.8) Stillbirth (7) Preterm (17.8) | 68.2 |

The meta-analysis by Maze et al. provides a comprehensive synthesis of 22 studies from 1996-2018.13

Meta-analysis of 22 studies.

ASA, aspirin; HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets; HTN, hypertension; IFN, interferon; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; MPNU, myeloproliferative neoplasm unclassified; NOS, not otherwise specified; pIFN, pegylated interferon.

MPN patients, however, have higher rates of other pregnancy complications, most commonly early spontaneous abortions before 20 weeks. Estimates for early spontaneous abortions in MPN patients range from 25%-50% in studies,13,17 although a recent population-based study matching 1141 MPN patients to normal controls found only a trend toward increased miscarriage rates.6 Other pregnancy complications that are increased include stillbirth, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm labor. A meta-analysis of 1210 MPN pregnancies by Maze et al noted preeclampsia as the most common adverse event, with a pooled incidence of 3.1%.13 A recent Swedish age-matched population study of 342 MPN pregnancies noted increased rates of preterm birth (14% vs 4%) and low birth weight (10% vs 4%) compared to controls.18 Stillbirths across multiple studies are in the 1% range (Table 1), higher than in the general population. Given these findings, referral to high-risk obstetrics with increased fetal monitoring is reasonable in pregnant MPN patients.

Venous thrombotic rates and hemorrhage are also increased in both pregnancy and MPN. A 2017 meta-analysis of 756 MPN pregnancies found the absolute VTE risk in the antepartum and postpartum settings to be 2.5% and 4.4%,19 respectively, and Maze et al reported pooled incidences of VTE to be 1.5%.13 In comparison, VTE complicates 0.1%-0.2% of pregnancies in the general population.20 Bleeding may also be increased in MPN patients, with Landtblom et al noting a trend toward increased bleeding complications in MPN pregnancies compared to age-matched controls (14% vs 9%, P = 0.11)18 and increased bleeding complications reported in an analysis of 129 PV pregnancies.15 Although mutations in JAK2 are known to increase the risk of thrombosis in MPN patients, it is unclear if mutational status also predicts thrombosis or other pregnancy complications, with some studies finding associations of the JAK2 mutation with early and late pregnancy loss,21,22 and other studies finding no associations.13,23 Therefore at this time, there are no changes in pregnancy management of MPN patients based on driver mutation status.

Management of pregnancy in MPN patients

Given the limited data regarding pregnancy outcomes in MPN patients, recommendations for management are based on extrapolation from similar patient populations (ie, other thrombophilias) as well as expert opinion. We review major recommendations and treatment decisions for pregnancy management in MPN patients (Table 2).

Practice recommendations for MPN patients from the preconception to postpartum period

| Preconception |

| • Detailed obstetric history and risk assessment • Avoid estrogen-containing contraceptives, discussion of cytoreductive agents and fertility • Stop hydroxyurea 3 months prior to conception • IVF and infertility: consider optimization of blood counts, LMWH prophylaxis for IVF |

| Pregnancy |

| • Low-dose aspirin • Consider LMWH prophylaxis if additional thrombotic risk factor present • Target Hct goals adjusted to gestational age • Cytoreduction in high-risk pregnancies* • Increased monitoring and consideration of cytoreduction in persistently high blood counts • High-risk obstetrics/maternal fetal medicine for increased fetal monitoring |

| Postpartum |

| • LMWH prophylaxis +/- aspirin for 6 weeks postpartum • Breastfeeding: LMWH, aspirin, and IFN preferred agents |

| Preconception |

| • Detailed obstetric history and risk assessment • Avoid estrogen-containing contraceptives, discussion of cytoreductive agents and fertility • Stop hydroxyurea 3 months prior to conception • IVF and infertility: consider optimization of blood counts, LMWH prophylaxis for IVF |

| Pregnancy |

| • Low-dose aspirin • Consider LMWH prophylaxis if additional thrombotic risk factor present • Target Hct goals adjusted to gestational age • Cytoreduction in high-risk pregnancies* • Increased monitoring and consideration of cytoreduction in persistently high blood counts • High-risk obstetrics/maternal fetal medicine for increased fetal monitoring |

| Postpartum |

| • LMWH prophylaxis +/- aspirin for 6 weeks postpartum • Breastfeeding: LMWH, aspirin, and IFN preferred agents |

See Table 3.

Hct, hematocrit; IFN, interferon.

Aspirin use

In pregnancy, low-dose aspirin has been demonstrated as safe and is recommended in obstetric patients at risk for preeclampsia.24 Multiple studies have shown that aspirin is associated with decreased fetal loss in MPN patients.13,23,25 Aspirin is associated with a small increased risk of bleeding in pregnancy.24 However, as aspirin is mostly a low-risk intervention and is associated with improved MPN pregnancy outcomes, we generally continue low-dose aspirin in all MPN patients who are pregnant, including in non-JAK2 mutated patients. Aspirin may be deferred in patients with a bleeding phenotype, including patients with acquired von Willebrand disease, and von Willebrand activity and antigen levels can be checked in patients with extreme thrombocytosis (ie, platelets >1000 × 109/L) before pregnancy and during the third trimester. Of note, platelets and von Willebrand levels improve with pregnancy, with most ET patients normalizing von Willebrand levels by the third trimester.26 If initially deferred, aspirin can be reasonably reinitiated at that time.

Low-molecular-weight heparin

The risk of bleeding with prophylactic LMWH (ie, 40 mg daily) during pregnancy is estimated to be around 0.5%.27 In general, expert guidelines recommend the use of prophylactic LMWH when the thrombotic risk is estimated to be 2 to 3 times higher than the major bleeding risk, based on the relatively higher case-fatality rate of bleeding compared to VTE.11 There is likely to be a net clinical benefit of LMWH prophylaxis when the thrombosis risk is >3% and net clinical harm when the risk is <1%; an unclear risk/benefit ratio exists when the risk is 1%-3%, requiring individualized and shared decision-making. In the absence of clear clinical data, this risk-benefit analysis can be applied to MPN pregnancies.

As discussed in the previous section, thrombotic risk in MPN pregnancies likely falls in the 1%-3% gray zone, although there are data to suggest a more significant thrombosic risk (>3%) during the postpartum period.13,19 For this reason, we typically offer prophylactic LMWH in the 6-week postpartum period and discuss the addition of LMWH in the antepartum period in patients with an additional thrombotic risk factor (prior estrogen-related thrombosis or concomitant strong thrombophilia). This is consistent with expert opinions. including National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,12,17,28 and, of note, studies have not shown differing rates of bleeding or thrombosis in MPN pregnancies treated or not treated with prophylactic LMWH.13 For patients who have a preexisting indication for therapeutic anticoagulation, the anticoagulant should be switched to therapeutic weight-based dosing of LMWH.

Cytoreduction

A significant risk factor for adverse outcomes in MPN pregnancies is a prior history of pregnancy complications, including multiple early pregnancy losses, stillbirth, preterm labor, and preeclampsia.23,25 As this may be related to placental dysfunction from the MPN, cytoreduction should be considered in MPN women with a high-risk pregnancy (Table 3). Cytoreduction should also be continued in patients who have a preexisting indication for cytoreduction and should be discussed in patients with a relative indication for cytoreduction, such as those with acquired von Willebrand disease. If cytoreduction is needed during pregnancy and the patient was previously on hydroxyurea, it is recommended that the cytoreductive agent be switched to an interferon 3 months prior to conception.

High risk pregnancies in MPN patients and indications for anticoagulation and cytoreduction

| Indications for anticoagulation |

| • Prior indication for anticoagulation: switch to therapeutic LMWH • Prior thrombotic event included estrogen-related: consider prophylactic LMWH • Concomitant high-risk thrombophilia +/- family history of thrombosis: consider prophylactic LMWH • IVF pregnancy (first 12 weeks): consider prophylactic LMWH |

| Indications for cytoreduction |

| • Prior indication for cytoreduction: switch to IFN • >3 unexplained consecutive pregnancy losses at <10 weeks: consider cytoreduction • >1 late pregnancy losses at >10 weeks: consider cytoreduction • Prior pregnancy complications including severe preeclampsia and placental insufficiency leading to <34 week fetus with IUGR: consider cytoreduction • Inability to maintain Hct at <45% with therapeutic phlebotomy: consider cytoreduction • Extreme thrombocytosis with acquired von Willebrand: consider cytoreduction • Significant antepartum or postpartum hemorrhage: consider cytoreduction |

| Indications for anticoagulation |

| • Prior indication for anticoagulation: switch to therapeutic LMWH • Prior thrombotic event included estrogen-related: consider prophylactic LMWH • Concomitant high-risk thrombophilia +/- family history of thrombosis: consider prophylactic LMWH • IVF pregnancy (first 12 weeks): consider prophylactic LMWH |

| Indications for cytoreduction |

| • Prior indication for cytoreduction: switch to IFN • >3 unexplained consecutive pregnancy losses at <10 weeks: consider cytoreduction • >1 late pregnancy losses at >10 weeks: consider cytoreduction • Prior pregnancy complications including severe preeclampsia and placental insufficiency leading to <34 week fetus with IUGR: consider cytoreduction • Inability to maintain Hct at <45% with therapeutic phlebotomy: consider cytoreduction • Extreme thrombocytosis with acquired von Willebrand: consider cytoreduction • Significant antepartum or postpartum hemorrhage: consider cytoreduction |

IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

Interferon-α has historically been favored in MPN pregnancies and is associated with improved birth rates.13 However, interferon-α is difficult to tolerate, and pegylated interferon-α is now primarily used. There has been retrospective and anecdotal experience demonstrating the safety of pegylated interferon-α in pregnancy,29-32 although given a relative lack of data, it continues to hold a Class C rating for pregnancy. When cytoreduction is needed in pregnancy, we typically recommend pegylated interferon-α while acknowledging that there are unknown risks to fetal development, particularly in the first trimester. Options, including holding off on pegylated interferon-α between conception and the second trimester, should be discussed with the patient. Other agents, including anagrelide and ruxolitinib, have demonstrated teratogenic effects in animal studies, and no human safety data exist for these agents;33,34 therefore, they are not recommended. There have been case reports that include pregnant women treated with ropeginterferon-alfa-2b35,36 with no adverse events noted, although more safety data are needed before ropeginterferon-alfa-2b can be routinely recommended in pregnancy.

Therapeutic phlebotomy and targeted blood counts

During normal pregnancy, there is an expected 5 g/dL decline in hemoglobin corresponding to a physiologic increase in plasma volume. For this reason, PV patients frequently will not need therapeutic phlebotomy during pregnancy. There are no clear data regarding recommended hematocrit thresholds in MPN pregnancy, and blood cell counts have not been shown to be associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes in MPNs.23 However, some expert opinions target normal hematocrit values as adjusted for gestational age.12 Difficulty meeting these thresholds despite therapeutic phlebotomy may be an indication for initiating cytoreduction. Phlebotomy may also worsen iron deficiency, which frequently occurs in pregnancy. We caution against routine iron supplementation unless recommended by the hematologist, given the potential for increasing hematocrit levels above therapeutic goals.

Platelet counts also decline by 20% in normal pregnancy; this is thought to be related to hemodilution and increased peripheral consumption. Platelet declines can be particularly exaggerated in ET patients, with many patients experiencing normalization of platelet counts by delivery. We followed longitudinal blood counts of 52 ET patients and found an average platelet decline of 43% throughout pregnancy, with the majority of platelet counts returning to the patients' baseline within a month of delivery.23 We also found that significant declines in platelet counts predicted improved pregnancy outcomes, suggesting that those who have persistently high platelet counts warrant closer monitoring, although other studies have found no associations between platelet counts and outcomes.22 Given the quick rebound of platelets in the postpartum period, and the fact that von Willebrand levels also drop significantly after delivery, ET patients with extreme thrombocytosis may be at risk for postpartum bleeding complications, especially if treated with LMWH and aspirin. Cytoreduction should be considered on an individualized basis.

CLINICAL CASE (continued): DURING PREGNANCY

Upon a review of this patient's obstetric history, it was determined that she has an average-risk pregnancy. It is recommended she continue 81 mg of aspirin daily without cytoreduction. The risks and benefits of LMWH prophylaxis are discussed, and given no other thrombotic risk factors, the decision is to proceed with aspirin during pregnancy and LMWH prophylaxis with aspirin in the postpartum period.

After pregnancy

Breastfeeding

Special consideration should be made for mothers who wish to breastfeed. LMWH and aspirin are both considered safe with breastfeeding. Pegylated interferon-α has little penetration into breastmilk and is poorly absorbed orally; therefore, it is likely safe with lactation.37 Hydroxyurea is present in breastmilk and generally discouraged with breastfeeding, although recommendations are weak.38 There is little human lactation data for other agents, including ruxolitinib or anagrelide, and, for this reason, the manufacturers discourage the use of these agents by breastfeeding mothers. For these reasons, we prefer the use of pegylated interferon-α if cytoreduction is needed in mothers with an MPN who wish to continue breastfeeding.

Conclusions

As pregnancy is increasingly encountered in MPN patients, more population-specific data are needed to guide individualized recommendations. There is a dearth of evidence surrounding the impact of an MPN on fertility, including outcomes and risk factors. Much of the existing data on MPNs in pregnancy surrounds ET patients, and so the extension of recommendations to PV, MF, or prefibrotic MF patients also needs to be evaluated more fully. Individualized care with multidisciplinary involvement may be needed for rarer situations, such as pregnant MF patients with splenomegaly or young MPN patients who have Budd Chiari syndrome and portal hypertension. Finally, with the growing use of pegylated interferon-α in MPN patients, particularly at younger ages, more safety data are needed regarding its use in pregnancy. However, despite these limitations, there have been multiple excellent reviews, studies, and meta-analyses that provide some guidance for the management of pregnancy in MPNs, such that patients can be reassured that with expert care, they can expect a healthy pregnancy and baby.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Joan How: no competing financial interests to declare.

Gabriela Hobbs: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Joan How: Nothing to disclose.

Gabriela Hobbs: Nothing to disclose.