Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a highly prevalent disorder characterized by a small bone marrow plasma cell or lymphoplasmacytic clone (less than 10%) that produces a small amount of monoclonal paraprotein without associated organ damage. Most patients with MGUS display benign behavior indefinitely, but some progress to an overt malignancy, and others develop organ damage despite no increase in monoclonal protein, resulting in the so-called MG of clinical significance (MGCS). This concept includes different disorders depending on the organ involved, and among them, MG of neurological significance (MGNS) constitutes a real challenge from both a diagnostic and therapeutic point of view. Diagnosis is particularly difficult due to MGNS's heterogeneous clinical presentation and common lack of a diagnostic biopsy. On the other hand, the complexity of treatment lies in the lack of standardized regimens and the common irreversibility of neurological damage. Focusing on the neurological manifestations of MGUS affecting the peripheral nervous system, we describe 3 illustrative cases from daily practice and discuss different aspects of diagnosis to treatment, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary management based on the close collaboration of neurologists and hematologists.

Learning Objectives

Describe the diagnostic approach to MGNS, focusing on the peripheral nervous system

Evaluate the available treatment strategies for MGNS, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary management

Introduction

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a highly prevalent disorder characterized by a small clone of bone marrow plasma cells or lymphoplasmacytic cells (fewer than 10%) that produce a small amount of monoclonal (M) paraprotein (below 30 g/L) and no associated organ damage.1 Unlike non–immunoglobulin M (IgM) MGUS, the diagnosis of IgM MGUS is established in patients who have IgM paraprotein with fewer than 10% bone marrow plasma cells (IgM MGUS of plasma cell type) or lymphoplasmacytic cells (IgM MGUS not otherwise specified), lack lymphoplasmacytic B-cell aggregates sufficient for a diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, and have no associated symptoms such as cytopenias, hyperviscosity, lymphadenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly.2 Despite being labeled a premalignant disorder, most patients remain asymptomatic indefinitely with no therapeutic intervention required. Only a small proportion progress to an overt malignancy such as multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, or another lymphoproliferative disorder. However, another group of patients develop organ damage despite no increase in M protein, resulting in the so-called monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance (MGCS).3

MGCS is a heterogeneous concept that includes several disorders that can also be classified according to different criteria such as the mechanisms of tissue injury, type of M protein, or type of specific organ involvement. The mechanisms of tissue injury described include the deposition of monoclonal Ig (either all or part of it, organized or nonorganized), autoantibody activity, complement alternative pathway activation, or cytokine-mediated damage.3 However, much is still unknown about the pathophysiology of these diseases, so a classification based on the type of M protein seems more practical, distinguishing between IgM and non-IgM MGCS.4 Finally, a clinically guided classification defines these entities according to the involved organ. The kidney is the most frequently and well-studied organ affected (monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance), followed by the nervous system and skin, with less frequent reports involving the eyes or the coagulation system.5,6 This classification is particularly useful when MGCS involves a single organ.

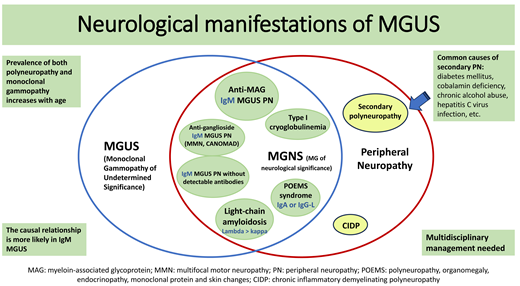

Among these diseases, monoclonal gammopathy of neurological significance (MGNS) constitutes a real challenge, both diagnostically and therapeutically. Diagnosis is particularly difficult due to its heterogeneous clinical presentation and common lack of a diagnostic biopsy, unlike other MGCSs. Additionally, therapy has not been standardized, and few clinical trials exist testing various interventions, compounded by the frequent irreversibility of neurological damage. In this context, the high prevalence of M protein detection in patients with otherwise unexplained peripheral neuropathies (10%) and the progressive increase in both findings (neuropathy and gammopathy) with age forces consideration of a noncausal but coincidental relationship to avoid unnecessary and potentially toxic therapies.7 For reasons of scope, we focus on the neurological manifestations affecting the peripheral nervous system, excluding the central and autonomic nervous systems.

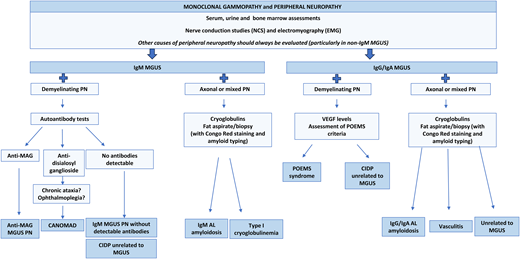

Therefore, the first step in the diagnostic approach for a patient with peripheral neuropathy (PN) and monoclonal gammopathy is to exclude common causes of secondary polyneuropathy, such as diabetes mellitus, cobalamin deficiency, chronic alcohol abuse, or hepatitis C virus infection, among others. This is particularly relevant in the context of an IgG or IgA MGUS, which more rarely cause PN compared to IgM MGUS. For that purpose an accurate medical history and complete physical examination are essential. Nerve conduction studies and electromyography allow characterization of the neuropathy as demyelinating, axonal, or mixed. Characterization of the monoclonal gammopathy is also mandatory, including serum, urine, and bone marrow assessments. Depending on the type of neuropathy and M protein (Figure 1), further investigations might be considered, such as vitamin B12 levels; tests for HIV, hepatitis C virus, and Lyme disease; autoantibody tests such as antinuclear antibodies, antibodies against myelin-associated glycoprotein (anti-MAG), and GM1-ganglioside (anti-GM1); cryoglobulin detection; serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); endocrine screening tests; imaging examinations to rule out lymphadenopathy or bone lesions; cardiac evaluation; fat pad aspiration for amyloid deposits; or nerve biopsy in selected cases (Table 1). This multidisciplinary approach requires the participation of a neurologist, neurophysiologist, and hematologist. With all this information, a diagnosis can be established and specific treatment considered, along with optimal supportive care.8,9 Three illustrative examples are presented below.

Diagnostic approach of PN in the context of an MGUS according to the type of neuropathy and M protein isotype. Adapted with permission from Visentin et al.4

Diagnostic approach of PN in the context of an MGUS according to the type of neuropathy and M protein isotype. Adapted with permission from Visentin et al.4

Diagnostic assessment of patients with PN and monoclonal gammopathy

| 1. Complete medical history |

| 2. Physical/neurological exam |

| 3. PN characterization: nerve conduction studies and electromyography |

| 4. Monoclonal gammopathy characterization: a. Renal function, serum calcium, and complete blood count b. Serum/urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation c. Serum Ig levels d. Serum free light chain levels e. 24-h urine excretion f. Bone marrow aspirate and/or biopsy: morphology, flow cytometry, molecular and cytogenetic analysis based on findings, such as MYD88 L265P mutation analysis in IgM MGUS, and FISH for t(11;14) in AL amyloidosis |

| 5. Other investigations according to previous findings: a. Serum cobalamin levels b. Cryoglobulins c. Testing for HIV, HCV, and, if indicated, syphilis and Lyme disease d. Autoantibodies: antinuclear antibodies, anti-MAG, and, if required, anti-HNK1, anti-GM1, disialosil ganglioside or anti-sulfatides antibodies e. Serum levels of VEGF f. Endocrine screening of the 4 major endocrine axes: gonadal, thyroid, glucose metabolism, and adrenal g. Imaging assessment: skeletal survey, MRI, CT, or positron emission tomographic CT h. Cardiac evaluation: serum troponin and NT-proBNP levels, electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and/or MRI i. Fat pad aspiration with Congo red staining and, if positive, amyloid typing j. Nerve biopsy |

| 1. Complete medical history |

| 2. Physical/neurological exam |

| 3. PN characterization: nerve conduction studies and electromyography |

| 4. Monoclonal gammopathy characterization: a. Renal function, serum calcium, and complete blood count b. Serum/urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation c. Serum Ig levels d. Serum free light chain levels e. 24-h urine excretion f. Bone marrow aspirate and/or biopsy: morphology, flow cytometry, molecular and cytogenetic analysis based on findings, such as MYD88 L265P mutation analysis in IgM MGUS, and FISH for t(11;14) in AL amyloidosis |

| 5. Other investigations according to previous findings: a. Serum cobalamin levels b. Cryoglobulins c. Testing for HIV, HCV, and, if indicated, syphilis and Lyme disease d. Autoantibodies: antinuclear antibodies, anti-MAG, and, if required, anti-HNK1, anti-GM1, disialosil ganglioside or anti-sulfatides antibodies e. Serum levels of VEGF f. Endocrine screening of the 4 major endocrine axes: gonadal, thyroid, glucose metabolism, and adrenal g. Imaging assessment: skeletal survey, MRI, CT, or positron emission tomographic CT h. Cardiac evaluation: serum troponin and NT-proBNP levels, electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and/or MRI i. Fat pad aspiration with Congo red staining and, if positive, amyloid typing j. Nerve biopsy |

FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 76-year-old woman presented with progressive, chronic, distal symmetrical dysesthesias over the past year. Neurological examination and electrophysiological studies demonstrated a demyelinating polyneuropathy. Laboratory tests revealed an IgMκ paraprotein of 2 g/L. Antibodies against MAG by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were strongly positive (over 70 000 Bühlmann units), while ganglioside antibodies were absent. Bone marrow aspirate showed 8% lymphocytes without morphologic or immunophenotypic abnormalities, and MYD88 L265P mutation was not detected by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction. Given this context, the patient was diagnosed with anti-MAG PN related to IgM MGUS. Due to significant disability, treatment with 4 weekly doses of rituximab at 375 mg/m2 was administered, resulting in mild neurological improvement in the following months. Five years later, the patient remained clinically stable with a persistent small IgMκ M protein only detectable by immunofixation.

IgM MGUS polyneuropathy

Polyneuropathy is the most frequent neurological syndrome associated with monoclonal gammopathies.10 This association is stronger and more frequent when the paraprotein is an IgM, either in the context of an IgM MGUS or Waldenström macroglobulinemia.11,12 It typically presents with predominantly sensory deficits in a symmetrical, length-dependent distribution (affecting the lower limbs before the upper limbs), causing slowly progressive disability over months to years. This clinical syndrome is also known as DADS-M, which stands for distal acquired demyelinating symmetric polyneuropathy with monoclonal gammopathy.8 A high prevalence of the MYD88 L265P mutation has been described in patients with this disorder, so it is very rare not to find it, as occurred in our patient.13 Interestingly, more than 50% of patients with IgM MGUS PN have detectable specific autoantibody activity. In most cases these antibodies are directed against MAG, while a lower proportion have detectable GM1 antibodies. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can show high titers of anti-MAG antibodies with good specificity, although titers are not linked to symptom severity and should not be used to monitor response to therapy. When anti-MAG antibodies are not detected, testing for antibodies against human natural killer-1 (HNK1), an epitope shared by NK lymphocytes and several components of the peripheral nerve myelin, may be useful for diagnosing anti-MAG neuropathy and could even be useful for disease monitoring.14,15 Electrophysiological studies demonstrate a demyelination pattern with slow conduction velocities and prolonged distal motor and sensory latencies.16,17

Once the diagnosis is established, clinicians should consider the functional impact of neurological damage together with the patient's characteristics to define an appropriate therapeutic approach. Patients presenting with distal paresthesia without gait imbalance can be managed conservatively with exercise and balance training. In contrast, patients presenting with gait ataxia, falls, or muscle weakness require an early intervention to prevent irreversible axonal damage.18 In this sense, 2 small clinical trials with rituximab did not demonstrate clinical benefit but showed improvement in secondary end points, suggesting some functional benefit in 30% to 50% of patients, later supported by a systematic review.19-21 Despite this, organ response is usually limited to stabilization of the neurological disease, as was described in our patient. Other therapeutic options include intravenous Igs (IVIgs) or corticosteroids, although neurological stabilization is less frequently achieved.11,22 More recently, a small prospective case series based on immunochemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and prednisolone reported benefits in IgM PN while ibrutinib is also a promising agent with high rates of hematologic and neurological response.23-25 Moreover, the combination of acalabrutinib and rituximab has demonstrated activity in a prospective clinical trial with hematologic responses in 86% of patients and neurological improvement in 57%.26 Given the lack of standardized regimens, treatment following the guidelines for Waldenström macroglobulinemia is recommended.8

Some patients without detectable anti-MAG antibodies show positivity against gangliosides. In those with anti-GM1 antibodies, motor neuropathy is the main clinical feature (multifocal motor neuropathy), and as in anti-MAG IgM MGUS PN, single-agent rituximab is recommended as first-line therapy, while ibrutinib is the most promising option in refractory patients. Less frequently, a chronic ataxic neuropathy with mixed axonal and demyelinating features associated with ophthalmoplegia, IgM paraprotein, cold agglutinins, and antibodies directed against disialosyl ganglioside (anti-GD1b, anti-GT1b, or anti-GQ1b) converges in a rare disorder coined CANOMAD. In these patients, IVIg and rituximab have shown clinical benefit.8 Finally, patients with IgM MGUS PN and nondetectable autoantibodies usually present with a painless, chronic distal neuropathy with sensory symptoms sometimes associated with tremor or ataxia. Electrophysiological studies also show a demyelization pattern.27,28 In cases of significant disability or progressive symptoms, these patients could be treated with an IVIg as the first option, while plasma exchange, rituximab alone or in combination with alkylating agents, or ibrutinib could be considered in unresponsive cases.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 36-year-old man with a relevant medical history of MGUS and JAK2-mutation negative thrombocytosis detected 4 and 2 years before presentation, respectively, complained of paresthesia and weakness in his distal lower limbs, leading to progressive difficulty in walking over the past 6 months. Electrophysiological studies demonstrated a demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy with signs of distal axonopathy. On physical examination he also presented with peripheral edema and multiple cutaneous hemangiomas on the trunk. Laboratory tests revealed a high platelet count of 978 × 109/L and a small serum M protein IgAλ of 1.5 g/L, without endocrine abnormalities. VEGF measurement was not yet available at our institution (2007). A bone marrow aspirate showed 7% plasma cells with lambda restriction by immunophenotypic analysis. A computed tomographic (CT) scan found small sclerotic bone lesions in both humeri and his proximal left femur. The diagnosis of POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes) syndrome was established, and the patient was treated with high-dose melphalan and stem cell rescue. He achieved a complete hematologic response and, over time, a mild improvement in his polyneuropathy.

POEMS syndrome

POEMS syndrome is a rare multisystem disease with unknown pathogenesis, classified as a plasma cell dyscrasia. Although neuropathy is the dominant clinical feature, the syndrome is characterized by a constellation of manifestations, including but not limited to those referred to in the acronym: polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes.29 Symptoms typically start with distal and symmetrical tingling, numbness, and/or neuropathic pain in the hands and feet, progressing proximally, with motor involvement following the sensory symptoms and leading to progressive weakness within weeks or months. Electrophysiologic studies typically reveal demyelinating but also axonal features of polyneuropathy, which can be very useful in differentiating POEMS from other entities such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP), with which it is often confused.30 On the other hand, the serum M protein is usually of small size (as well as the plasma cell clone in the bone marrow) and almost always of IgAλ or IgGλ isotype. The diagnosis is based on a composite of clinical and laboratory features (Table 2), which should be carefully reviewed to avoid a missed diagnosis.31,32 Accordingly, our patient fulfilled both mandatory major criteria, 1 major criteria, and 2 minor criteria, for POEMS syndrome.

Criteria for the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome: diagnosis is confirmed when both mandatory major criteria, 1 of the 3 major criteria, and 1 of the 6 minor criteria are present

| Mandatory major criteria |

| • Polyneuropathy (typically demyelinating) • Monoclonal plasma cell–proliferative disorder (almost always lambda) |

| Major criteria |

| • Castleman disease • Sclerotic bone lesions • Increased levels of VEGF |

| Minor criteria |

| • Organomegaly (splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, or lymphadenopathy) • Extravascular volume overload (edema, pleural effusion, or ascites) • Endocrinopathy (adrenal, thyroid,a pituitary, gonadal, parathyroid, pancreatica) • Skin changes (hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, glomeruloid hemangiomata, plethora, acrocyanosis, flushing, white nails) • Papilledema • Thrombocytosis or polycythemia |

| Other known associations |

| Clubbing, weight loss, hyperhidrosis, pulmonary hypertension or restrictive lung disease, thrombotic diathesis, diarrhea, low vitamin B12 values |

| Mandatory major criteria |

| • Polyneuropathy (typically demyelinating) • Monoclonal plasma cell–proliferative disorder (almost always lambda) |

| Major criteria |

| • Castleman disease • Sclerotic bone lesions • Increased levels of VEGF |

| Minor criteria |

| • Organomegaly (splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, or lymphadenopathy) • Extravascular volume overload (edema, pleural effusion, or ascites) • Endocrinopathy (adrenal, thyroid,a pituitary, gonadal, parathyroid, pancreatica) • Skin changes (hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, glomeruloid hemangiomata, plethora, acrocyanosis, flushing, white nails) • Papilledema • Thrombocytosis or polycythemia |

| Other known associations |

| Clubbing, weight loss, hyperhidrosis, pulmonary hypertension or restrictive lung disease, thrombotic diathesis, diarrhea, low vitamin B12 values |

Diabetes mellitus and thyroid abnormalities alone are not sufficient to meet the minor criterion due to their high prevalence.

Adapted with permission from Dispenzieri.32

Regarding therapy, it aims to eradicate the plasma cell clone with the ultimate goal of improving the clinical manifestations, particularly the PN, which might be achieved with 2 different approaches. In patients with a limited number of osteosclerotic bone lesions (1 to 3) and without clonal plasma cell infiltration found in the bone marrow, radiation therapy to the bone lesions (up to 45 Gy) may improve the symptoms over the next 3 to 36 months and can even be curative. The addition of systemic therapy can be considered 6 to 12 months later depending on response evaluation.33 In contrast, patients with more than 3 bony lesions or significant bone marrow infiltration require systemic therapy. The greatest experience available has been obtained with alkylator-based therapy, either with oral melphalan and dexamethasone, with cyclophosphamide-based regimens, or particularly with intravenous high-dose melphalan in transplant-eligible patients.34-36 Additionally, immunomodulatory drugs (mainly lenalidomide combined with dexamethasone) and daratumumab-based combinations have shown promising results in this disease.37,38

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

Returning to our patient, 9 years later he presented with worsening of his sensorimotor polyneuropathy together with peripheral edema, pleural effusion, and ascites. Laboratory tests showed a hematologic relapse with the reappearance of a small serum M IgAλ paraprotein and an increase in serum VEGF levels up to 326 pg/mL (normal value <129 pg/mL). A positron emission tomographic CT scan revealed the known osteosclerotic bone lesions without radiotracer uptake. He was treated with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone with no response and received a second autologous transplant. With this, the patient achieved a very good partial hematologic response, normalization of VEGF levels, stabilization of his polyneuropathy, and disappearance of extraneurological manifestations.

CLINICAL CASE 3

A 43-year-old man was referred for evaluation of dysesthesias in his feet, which had persisted for 3 years and recently extended to his hands. Neurological examination and electrophysiological studies showed a mixed axonal large fibers polyneuropathy, with involvement of small fibers too. Further investigations revealed the presence of an IgGλ M protein of 7 g/L in serum, free lambda light chain in urine without significant proteinuria, and 3% plasma cells in the bone marrow aspirate. At that time (1999), the serum free light chain test was not available. No bone lesions were found by CT scan, nor was amyloid evident in the fat pad aspirate. Finally, a sural nerve biopsy demonstrated amyloid deposits in the endoneurial vessels by Congo red staining, exhibiting apple-green birefringence under polarized light, as well as a virtual disappearance of myelinated fibers. Amyloid typing by immunohistochemistry was positive for lambda light chain and negative for kappa light chain, protein A, and transthyretin. By then the patient required splints on both legs to ambulate. Once the diagnosis of light chain (AL) amyloidosis was established, the patient was treated with high-dose melphalan and stem cell rescue, achieving a complete hematologic response and stabilization of his polyneuropathy.

AL amyloidosis with involvement of peripheral nervous system

Involvement of the peripheral nervous system occurs in about 15% to 20% of patients with AL amyloidosis.9 The most common presentation is a length-dependent axonal polyneuropathy affecting both large and small fibers, initially sensory but potentially progressing to a sensorimotor neuropathy, as observed in our patient. It is usually part of a multisystemic disease, wherein neuropathy is not the dominant feature, the autonomic nervous system may also be involved, and bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome may be present. Therefore, isolated involvement of the peripheral nervous system is a very rare condition in AL amyloidosis and, unless confirmed by biopsy, should prompt consideration of other diagnostic options, including other forms of amyloidosis with a predominant neurological phenotype (such as transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis). For this reason, a nerve biopsy was performed on the aforementioned patient despite the associated risks of irreversible sequelae, such as pain, sensory loss, or weakness.39

In 2024, with the advent of novel therapies, a patient presenting with AL amyloidosis and severe PN would likely receive single-agent daratumumab as first-line treatment, replacing the traditionally used cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone regimen, to avoid the potential neurotoxicity of bortezomib.40 If this hypothetical patient had not achieved a complete hematologic response after daratumumab and neurologic deterioration persisted, consolidation with an autologous stem cell transplant could be considered, especially given his young age. This approach would need to balance the patient's frailty, potential transplant-related toxicity, and realistic expectations for organ improvement. Alternatively, stem cell transplantation could be delayed until hematologic relapse or disease progression.41 Additional treatment options include combinations based on immunomodulatory drugs (lenalidomide or pomalidomide), new-generation proteasome inhibitors, and BCL2 inhibitors like venetoclax, which has shown particular promise in patients with the t(11;14) translocation.40

In summary, the causal relationship between PN and non-IgM MGUS is less likely. In this scenario, other common causes of PN should always be ruled out, as previously stated. IgG/IgA MGUS PN displays more heterogeneous clinical and electrophysiological features with no associated specific antibodies, making it a real challenge to distinguish these entities from CIDP.42 When the patient presents with a rapidly progressive PN, the M protein is a lambda light chain, either alone or linked to an IgG or IgA, and electrophysiological studies show an axonal PN, AL amyloidosis and POEMS syndrome should be suspected.11 If these diagnoses and other causes of PN have been excluded, management of a non-IgM MGNS should follow the same approach as CIDP, particularly with an IVIg.42 Finally, supportive care is essential and cannot be overlooked. Nonpharmacological strategies include physical and occupational therapy, in addition to rehabilitation programs and orthotic devices. Pharmacological treatment is based on studies performed in patients with diabetic and other forms of neuropathy and typically involves gabapentinoids, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and sodium channel blockers.43,44 All of this should take place in the context of a multidisciplinary approach, with the aim to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of these diseases.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

M. Teresa Cibeira: no competing financial interests to declare.

Luis Gerardo Rodríguez-Lobato: no competing financial interests to declare.

Aida Alejaldre: no competing financial interests to declare.

Carlos Fernández de Larrea: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

M. Teresa Cibeira: Nothing to disclose.

Luis Gerardo Rodríguez-Lobato: Nothing to disclose.

Aida Alejaldre: Nothing to disclose.

Carlos Fernández de Larrea: Nothing to disclose.