Key Points

Low-intensity FeCl3-induced clots have a pocketed structure in which loosely adherent platelet infill leads to occlusion.

The Syk inhibitor BI 1002494 selectively impairs FeCl3 clot infill with no effect on puncture wound hemostasis.

Visual Abstract

Knowing structural organization of a clot at the single-cell level could lead to the development of drugs targeting specific structural features. We tested this premise in a murine femoral artery occlusion model using a narrow ferric chloride (FeCl3) application strip to limit induction intensity. Under these conditions, occlusive clot formation was sensitive to the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor BI 1002494, an indication of normative platelet response. Samples perpendicular or longitudinal to blood flow were imaged by montaged electron microscopy. Platelets were the predominant cell type. Tightly packed platelets were anchored to FeCl3-induced damaged portions of the vessel wall, and aggregates of tightly packed platelets extended inward. Overall, the clots had a structure in which loosely packed platelets, often discoid in shape and rich in α-granules, filled pockets within the clot surrounded by zones of tightly adherent platelets. Red blood cells (RBCs), mainly entrapped, squeezed, and polyhedral in shape, were distributed in scattered patches. Based on platelet morphology, any effect of RBCs on platelet activation extended for a short distance, ∼5 μm. In Syk inhibitor–treated mice, structural formation of an occlusion was strongly inhibited; infill was impaired, resulting in a highly porous clot rich in dispersedly aggregated discoid shaped platelets. Blood flow was normal, and inhibitor had no apparent effect on the structure of a femoral puncture wound clot. We suggest that BI 1002494 produced a selective inhibition of thrombus structure by depressing intraplatelet signaling below a crucial threshold in the high flow occlusion model, but not in the lower flow puncture wound model.

Introduction

Platelet aggregation in response to cardiovascular damage is central to both hemostasis, a physiological process that to leads to sealing a puncture wound, and thrombosis, a pathological process that can lead to myocardial infraction or stroke.1,2 Each has been studied experimentally in animal models, often using mice, or ex vivo, typically with isolated murine or human platelets. A limited number of popular in vivo experimental hemostatic models have emerged, for example, laser or needle prick damage to arterioles or venules, treatments that fail to produce profuse bleeding,3 or a larger diameter puncture to the jugular vein in which profuse bleeding occurs.4,5 Thrombus formation in these hemostasis models occurs at endogenous signaling levels. On the other hand, the signaling in the commonly used thrombosis model, ferric chloride (FeCl3)-induced arterial occlusion,6 although a useful predictive model for in vivo human consequences,7 may well depend on a confounding mix of artifactual FeCl3-induced protein and cell flocculation and heme release from damaged red blood cells (RBCs) vs endogenous signaling.8-10

Occlusive clot formation could be considered as an extension of the “core-and-shell” paradigm of hemostasis.11 In this paradigm, the hemostatic thrombus structure is conceptualized as a core of highly activated platelets proximal to the damaged vessel wall, and an outer shell of low activation, less tightly adherent platelets.12 Occlusion is then predicted to occur from overgrowth of the shell.13,14 On the other hand, volume electron microscopy approaches visualizing in detail the interior of larger puncture wounds have led to an alternative “cap-and-build” paradigm.5,15 In this paradigm, the thrombus is formed by local nucleated platelet capture, which leads to a vaulted structure in which the puncture hole is capped from the extravascular side rather than plugged.5 Extension of this framework to thrombosis raises the possibility that occlusion is due to the infill of “vaulted pockets” within the forming clot.

We used the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor BI 1002494 [(R)-4-16[naphthyridin-5-yloxy]-ethyl pyrrolidin-2-one16; opnMe program, Boehringer Ingelheim] as a tool to dissect structural differences between hemostasis and thrombosis, and hence test structural paradigms.17 Mechanistically, Syk kinase is a downstream effector of platelet immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) receptor proteins. The 2 ITAM receptor proteins in mice are glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and C-type lectin-like receptor 2 (CLEC-2),18 and in human platelets there is a third platelet ITAM receptor family member, Fc γ receptor IIA, which enhances integrin signaling in a Syk-dependent manner.19,20 GPVI knockout in mice produces a mild bleeding phenotype and a greater effect on thrombosis, while CLEC-2 is thought to have little role in hemostasis.21,22 Inhibiting Syk also selectively affects thrombosis vs hemostasis in mice.17 In the jugular vein puncture wound thrombus structure model, BI 1002494 has no effect on bleeding time and a minimal effect on jugular vein puncture thrombus structure.23 In striking contrast, GPVI knockout profoundly affects the organization of the intravascular puncture wound thrombus crown, producing a very fluffy crown in which platelets are loosely adherent, suggesting that interference with intracellular signaling level could be a more attractive therapeutic route than GPVI itself.23

Here we tested the fit between hemostatic paradigms and the structural organization of induced occlusive thrombi in a mouse FeCl3-induced occlusion model in the femoral artery. As a first step, we tested whether FeCl3 induction at a low intensity is occlusion sensitive to BI 1002494 and independent of entrapped RBCs, indicators of physiological relevance. Second, we defined, at nm resolution, the structural organization of occlusive clots, and how that related to femoral blood vessel wall damage and to paradigms of thrombus formation. Third, we characterized the comparative structure of any FeCl3-induced, femoral artery, thrombus residue formed in Syk inhibitor–treated mice vs that of a hemostatic puncture wound thrombus formed in the same artery, plus or minus BI 1002494. Our primary readout was the volume electron microscopy approach of wide-area transmission electron microscopy (WA-TEM), in which montaged full cross-section imaging of thrombus structure is achieved at nanometer resolution.5,15,24 To our surprise, Syk inhibition of occlusive clotting and accompanying maintenance of blood flow patency yielded a thrombus that consisted primarily of quite loosely aggregated, typically discoid shaped platelets, indicating a selective platelet activation state inhibition. There was no effect on the structural organization of femoral puncture wound thrombi. We suggest that high blood flow within central portions of the femoral artery likely contributed to these outcomes.

Materials and methods

Animals and reagents

Wild-type male and female C57BL/6 mice aged 8 to 12 weeks (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used in equal numbers. Protocols were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Reagents are described in previous publications.

BI 1002494 Syk inhibitor treatment

FeCl3-induced occlusive clot formation

Blood flow was monitored using a TS420 transit-time perivascular flowmeter and sonic probe. A small piece of Whatman filter paper, grade 4 (∼350 μm × ∼500 μm), was soaked with 0.5 μL of a 10% FeCl3 solution prepared immediately before use in deionized water. The filter paper was placed perpendicularly on the femoral artery and left for 3 minutes. Twenty minutes after FeCl3 treatment, the local arterial segment was excised and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.9% NaCl in 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 hour at room temperature and then 4°C overnight. Control, non–FeCl3-treated, femoral artery samples were treated similarly following exposure to deionized water-soaked filter paper. For Syk inhibitor–treated and related control mice, samples were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 10 minutes in situ, then excised, and further processed.25

Puncture wound clot formation24

A 33G syringe needle, 210 μm nominal diameter, was used to puncture the femoral artery. Five minutes after puncture, a transcardial perfusion was used to clear away blood cells, and then with 1% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 10 minutes. A fixative solution drip was started near but not directly over the clot site 2.5 minutes before the transcardial perfusion. Samples were further processed for WA-TEM.24,26,27

WA-TEM analysis

Montages were collected using SerialEM software and visualized with IMOD software (laboratory of David Mastronarde, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO). WA-TEM images were analyzed by desktop-based software, ZEISS Arivis Pro, and cloud-based deep learning technology, Zeiss Arivis Cloud software. Frames were stitched together with Arivis Pro software. Spacing between platelets was determined in Arivis Pro. For cloud-based analysis, 4 distinct components were trained and mapped: area of tightly packed platelets, elongated platelets, RBCs, and white blood cells (WBCs). Components were trained separately for artificial intelligence-driven deep learning using the Convolutional Neural Networks (ConvNets) algorithm (supplemental Figures 1 and 2).28

Study approval

This study received Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Results

Mild FeCl3-induced clotting is physiologically based

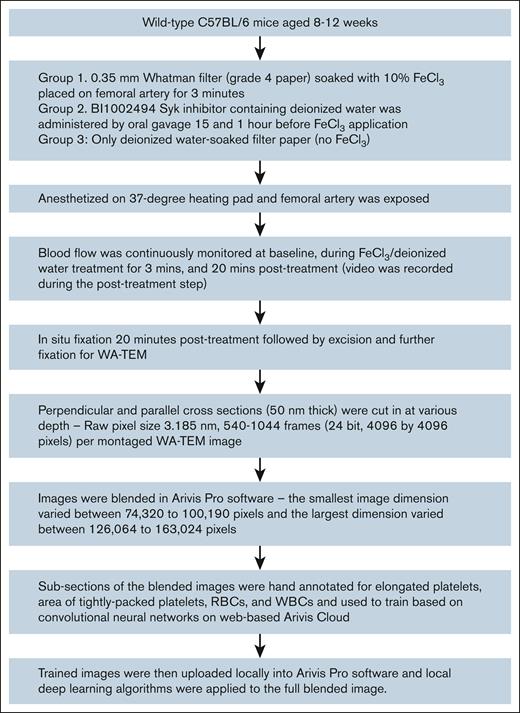

Workflow started with animal surgery, WA-TEM imaging, and ended with software-driven analysis (Figure 1). We used mild clot induction conditions, a small-sized filter strip (0.35-mm wide filter pad soaked in FeCl3) to induce clotting in the femoral artery of mice (Table 1). As 1 positive control for involvement of physiological platelet signaling pathways, we tested for sensitivity to the Syk inhibitor BI 1002494.17,23 As monitored by visual inspection and transonic flow metering (Figure 2; Table 1), in the control, no inhibitor, FeCl3 model, stable occlusive clots were formed at 80% incidence within 3 minutes of FeCl3-soaked filter paper removal, In contrast, in the FeCl3 + Syk model, there was only a 16% incidence of any occlusion (Table 1 and flow data examples; Figure 2). The observed occlusions were delayed in time and were unstable. Representative no-inducer and FeCl3-induced clotting examples are shown in Figure 2, and were chosen for further analysis. Note that the original image sizes are large, for example, 125 840 by 146 688 pixels, 3.185 nm pixel size, frame F, and hence images are displayed at various zooms, here 1% (100% zoom, full size), to highlight important structural features.

A workflow showing preparation of data from animal surgery to analysis of the data in advanced image analytical software.

A workflow showing preparation of data from animal surgery to analysis of the data in advanced image analytical software.

Overall occlusive clot formation following FeCl3 induction, 0.35 mm strip, on femoral artery (C57BL/6 wild-type mice)

| Clot formation . | FeCl3 treated . | FeCl3 + Syk inhibitor treated . |

|---|---|---|

| Occlusive clots, 3 minutes after FeCl3 removal | 17 (80%) | Delayed, 1 at 4 minutes, 1 at 6 minutes, unstable |

| None (not detected) | 4 (20%) | 10 (83%) |

| Total | 21 | 12 |

| Clot formation . | FeCl3 treated . | FeCl3 + Syk inhibitor treated . |

|---|---|---|

| Occlusive clots, 3 minutes after FeCl3 removal | 17 (80%) | Delayed, 1 at 4 minutes, 1 at 6 minutes, unstable |

| None (not detected) | 4 (20%) | 10 (83%) |

| Total | 21 | 12 |

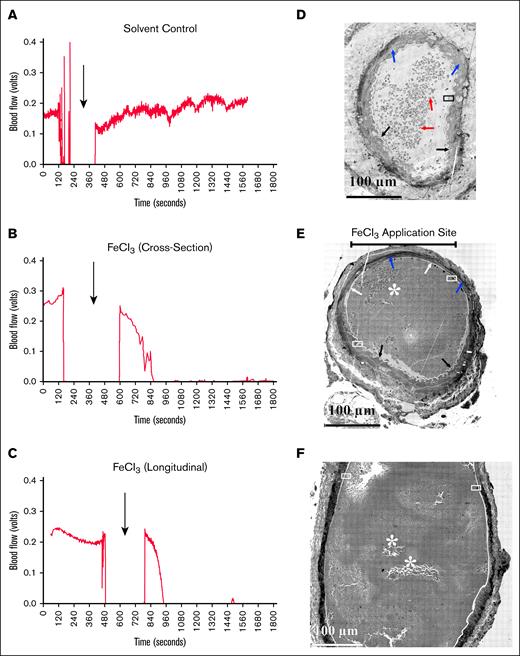

Examples of blood flow monitoring and corresponding artery structure. Comparison between blood flow (A-C) and morphology of murine femoral perpendicular cross-sections (C,E) and longitudinal section (F, parallel to flow from deionized water; A, solvent control; B-C, FeCl3-treated mice). Both cross-sections were from the middle of the FeCl3 application area. (A) Mock-treated sample showing underlying intima (pale, low staining circumferential ring). Blue arrows indicate the folded smooth muscle layer, and red arrows indicate RBC inside the arterial lumen. The inset is zoomed out in Figure 3A. (B) The upper bar marks the FeCl3 application site. White arrows point to flattened endothelial layer indicative of vascular damage; black arrows point to normal corrugated/folded endothelial layer; and blue arrows point to the smooth muscle layer. The arterial lumen itself is filled by a platelet-rich clot. The insets are zoomed out in panels B, C, and D, respectively. (C) Blood flow in the femoral artery was monitored and measured with a transit-time perivascular flowmeter and sonic probe. Arrows indicate the timing of the mock treatment. The initial segment was the flow signal detected before the mock treatment. The flow probe signal dropped out as fluid in the vessel’s surroundings was removed to prevent mock dilution. Fluid was reintroduced upon removal of the mock filter paper, and the flow probe again became functional. Following mock application, ∼20 minutes of probe flow signal data were collected. No dip in flow signal following treatment indicates no occlusion. (D) In this instance, FeCl3 was used instead of deionized water. A complete cessation of the blood flow signal with FeCl3 treatment indicates an occlusive clot. At this image zoom, the pockets of loosely adherent platelets are most obvious in the longitudinally section sample in panel F.

Examples of blood flow monitoring and corresponding artery structure. Comparison between blood flow (A-C) and morphology of murine femoral perpendicular cross-sections (C,E) and longitudinal section (F, parallel to flow from deionized water; A, solvent control; B-C, FeCl3-treated mice). Both cross-sections were from the middle of the FeCl3 application area. (A) Mock-treated sample showing underlying intima (pale, low staining circumferential ring). Blue arrows indicate the folded smooth muscle layer, and red arrows indicate RBC inside the arterial lumen. The inset is zoomed out in Figure 3A. (B) The upper bar marks the FeCl3 application site. White arrows point to flattened endothelial layer indicative of vascular damage; black arrows point to normal corrugated/folded endothelial layer; and blue arrows point to the smooth muscle layer. The arterial lumen itself is filled by a platelet-rich clot. The insets are zoomed out in panels B, C, and D, respectively. (C) Blood flow in the femoral artery was monitored and measured with a transit-time perivascular flowmeter and sonic probe. Arrows indicate the timing of the mock treatment. The initial segment was the flow signal detected before the mock treatment. The flow probe signal dropped out as fluid in the vessel’s surroundings was removed to prevent mock dilution. Fluid was reintroduced upon removal of the mock filter paper, and the flow probe again became functional. Following mock application, ∼20 minutes of probe flow signal data were collected. No dip in flow signal following treatment indicates no occlusion. (D) In this instance, FeCl3 was used instead of deionized water. A complete cessation of the blood flow signal with FeCl3 treatment indicates an occlusive clot. At this image zoom, the pockets of loosely adherent platelets are most obvious in the longitudinally section sample in panel F.

As a second test for physiological relevance, we assessed the effect of polyhedral RBCs on platelet activation. Previous reports suggest that damaged RBCs as exemplified morphologically by the occurrence of polyhedral RBCs provide a nonphysiological signal for FeCl3-induced occlusion.9-11 Under our mild FeCl3 induction conditions, WA-TEM analysis found variable short-range effects of polyhedral RBCs on platelet activation. Patches of entrapped polyhedral RBCs were sporadically distributed in small patches within the platelet-rich, induced occlusive clots (Figure 2E-F, asterisks). Platelets proximal to the polyhedral RBCs sometimes appeared to be highly activated, that is, organelle-free (Figure 3A). However, ∼5 μm distal to the patch, the platelets were less activated, retained organelles (dark dots), and were tightly packed together. As shown in Figure 3B, the effect of polyhedral RBC proximity was sometimes less. Considering the large diameter of the femoral artery (>200 μm), the rarity of entrapped polyhedral RBCs, and the evidence for any effect being very local, we conclude that the predominant signaling within the induced occlusions is physiologically based as indicated by Syk sensitivity.

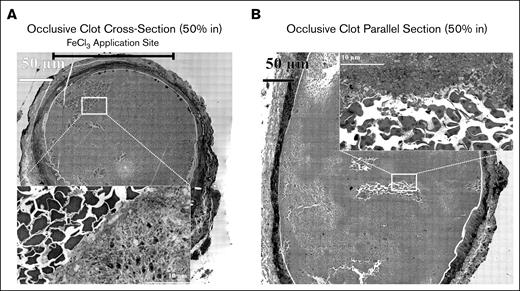

Detailed imaging of polyhedral RBCs and surrounding platelets. Higher zoom of perpendicularly (A) and longitudinally (B) sectioned occlusive clot showing the appearance of entrapped, polyhedral RBCs.

Detailed imaging of polyhedral RBCs and surrounding platelets. Higher zoom of perpendicularly (A) and longitudinally (B) sectioned occlusive clot showing the appearance of entrapped, polyhedral RBCs.

Assessment of site(s) of platelet attachment to the vessel wall

We next assessed femoral artery damage and its contribution to platelet adherence to the occluded vessel wall, by comparing the infoldings of the vessel wall along its interior and the state of the endothelial cell lining in solvent control (water-soaked pad) and FeCl3-treated arteries. As shown in Figure 2D, cross-section, solvent control, the endothelial layer, and underlying intima were corrugated (black arrows) along the entire vessel periphery. The vessel lumen contained mostly RBCs (red arrows). In contrast, the 2 detailed-analysis FeCl3-induced occlusions both showed extensive areas of flattened femoral artery vessel wall, suggesting relaxation of the associated smooth muscle layer (Figure 2E-F). In the perpendicular sectioned sample where the position of FeCl3 application was known, the vessel wall flattening was restricted to distances fanning out from the (bar) application site, and the lumen of the artery was filled with a platelet-rich clot (Figure 2E, cross-section). As expected, portions of the vessel under the smoothed endothelial/intima layers stained more darkly in the FeCl3-treated sample than in control (blue arrow), presumably due to iron accumulation. The remainder of the vessel wall had a normal corrugated interior surface (black arrows). This result indicates FeCl3-produced arterial damage was most proximal to the application site. In the longitudinal section (Figure 2F), flattening of the vessel wall was more general. In both the cross-section and the longitudinal examples, tight apposition of the clot to both flattened and variably corrugated areas of femoral artery vessel wall suggested platelets were wall adherent in both regions.

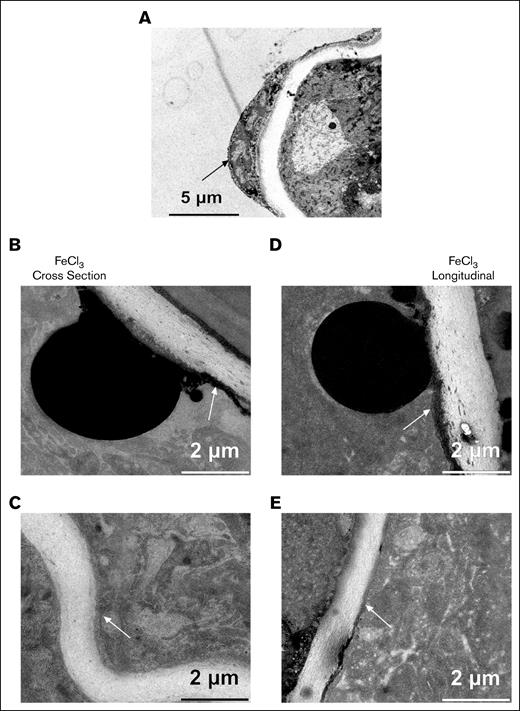

To investigate putative platelet attachment sites in detail, we zoomed montage display from 2% to between 30% and 100%, and examined 4 different regions (white boxes, Figure 2E-F). As expected, no platelets were attached to the intimal layer of the solvent control sample (Figure 4A). Endothelial cells, thickest at the cell nucleus and much thinner distal, were in firm contact with the underlying elastic lamina. Along the intimal layer in the FeCl3-treated examples (Figure 4B,D), several black spherical bodies (∼5-10 μm, presumably rich in iron, most likely damaged endothelial cell nuclei) were protruding from the endothelial cell layer. Such blackened bodies were not observed in the solvent control treated case, and we take them as a biological indicator of the application site (see Figure 2E for an example damage site marking). We observed an iron-rich endothelial layer, that is, a densely black thin layer that fanned in either direction from the application region. This layer is continuous with the block bodies. Adjacent platelets were tightly packed and lacked intracellular organelles, indicative of a high activation state, presumably due to direct anchoring to the damaged endothelial cells. Distal from the damaged endothelial layer and spherical black body, the platelets appeared to retain their organelles, suggesting a gradient of platelet activation (supplemental Figures 3 and 4). Distal from the application site, endothelial cell damage was less and black iron deposits were rarer (Figure 4E). A thin elongated layer of not very well-organized cells, presumably endothelial cells, appeared to line the intima (supplemental Figure 3, 50% zoom of the montage). We suggest that platelet anchoring was to these cells. Finally, in more distal areas that showed a corrugated intima with less platelet packing and in which a distinct, more intact endothelial cell layer was observed, there still appeared to be direct contact between platelets and endothelial cells suggestive of adhesion (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 4). The sparse platelet packing observed here suggests that apparent platelet endothelial layer adherence is not a result of platelet-platelet pressure (supplemental Figure 4, 100% montage zoom). In summary, the dominant form of platelet adherence to the damaged vessel wall appears to be to endothelial cells in various damage states.

High zoom imaging of the intimal layer of deionized water (solvent control) and an FeCl3-treated example. (A) Reference imaging of the mock-treated sample showing normal endothelial cells lining the vessel lumen. (B) FeCl3-treated femoral artery showing adherence of platelets to blackened endothelial cell layer. (C) Zoomed image showing attachment of platelets to a relaxed area of the endothelial intima layer, indicating minimal damage. (D) Zoomed imaging from FeCl3-treated sample showing platelet adherence to endothelial layer of corrugated intima. Arrows point to thin endothelial cell continuities along the underlying elastin-rich intima.

High zoom imaging of the intimal layer of deionized water (solvent control) and an FeCl3-treated example. (A) Reference imaging of the mock-treated sample showing normal endothelial cells lining the vessel lumen. (B) FeCl3-treated femoral artery showing adherence of platelets to blackened endothelial cell layer. (C) Zoomed image showing attachment of platelets to a relaxed area of the endothelial intima layer, indicating minimal damage. (D) Zoomed imaging from FeCl3-treated sample showing platelet adherence to endothelial layer of corrugated intima. Arrows point to thin endothelial cell continuities along the underlying elastin-rich intima.

Thrombus structure and platelet infill patterns within occlusive clots

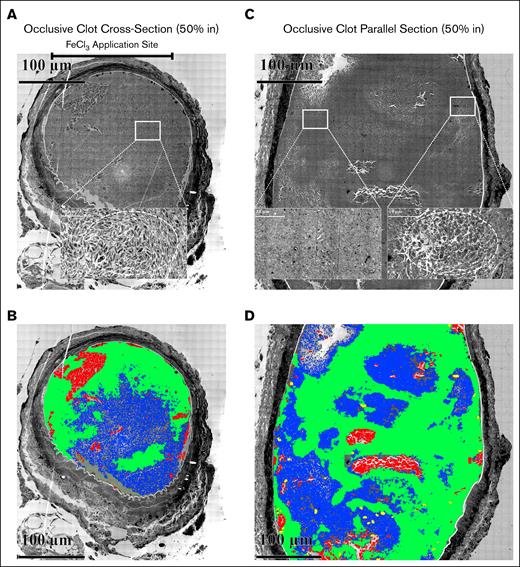

Following computer analysis based on platelet packing (supplemental Figure 5; “Materials and methods”), we observed that pockets (blue color, Figure 5B,D) of elongated, loosely adherent platelets (supplemental Figure 6) accumulated within the occlusive clots in pockets of varying size surrounded by a framing accumulation of tightly packed platelets (green color, Figure 5B,D). The images from which the computer analysis was derived are shown in Figure 5A-B and insets (see also supplemental Figures 7 and 8). In Figure 5A, perpendicular section, the loosely adherent, elongated platelets were mostly discoid in shape and retained their organelles (see inset). The parallel alignment of these platelets appeared to give a circular pattern (dashed circle) indicative of a swirled distribution and turbulent blood flow during clot formation. In contrast, in Figure 5B, longitudinal section, the loosely adherent platelet population appeared to be less elongated and to have more pseudopods (right inset); any circular pattern was less pronounced. The left inset shows the appearance of the tightly adherent platelets framing the pockets of more loosely adherent platelets. The computer analysis strongly indicates that the pocketed distribution of more loosely adherent apparent “infill” platelets is a key feature in both perpendicular and longitudinal sectioned femoral artery occlusive clots.

Occlusive clots 20 minutes following FeCl3 treatment. (A) Perpendicular section approximately middle of the thrombus. The upper bar marks the FeCl3 application site. The high-zoomed central section shows the organization of elongated platelets with few pseudopods, mostly discoid in shape and loosely packed spatially. (B) Parallel section approximately middle of the thrombus. The zoomed inset shows elongated platelets with several pseudopods, yet mostly discoid in shape and loosely packed spatially. (B,D) Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution of clot components (elongated platelets, area of tightly packed platelets, RBCs, and WBCs in both perpendicular and parallel sections within an occlusive clot). Following the training (details of cloud training are given in supplemental Figure 6), 4 files for individual clot components were downloaded. (A-B) The output of training images after applying those on blended images in Arivis Pro software. In panel A, the cellular components were mapped in a perpendicular section, 50% in of an occlusive clot. The trained files for each cellular components were uploaded to the Arivis Pro software, and were applied to the whole blended image using deep learning algorithm through a pipeline. Green, area of tightly packed platelets; blue, elongated platelets; red, RBCs; yellow, WBCs. The upper bar represents the FeCl3 application site. In panel B, the cellular components were mapped in a parallel section, 50% of an occlusive clot in Arivis Pro software using the same algorithm.

Occlusive clots 20 minutes following FeCl3 treatment. (A) Perpendicular section approximately middle of the thrombus. The upper bar marks the FeCl3 application site. The high-zoomed central section shows the organization of elongated platelets with few pseudopods, mostly discoid in shape and loosely packed spatially. (B) Parallel section approximately middle of the thrombus. The zoomed inset shows elongated platelets with several pseudopods, yet mostly discoid in shape and loosely packed spatially. (B,D) Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution of clot components (elongated platelets, area of tightly packed platelets, RBCs, and WBCs in both perpendicular and parallel sections within an occlusive clot). Following the training (details of cloud training are given in supplemental Figure 6), 4 files for individual clot components were downloaded. (A-B) The output of training images after applying those on blended images in Arivis Pro software. In panel A, the cellular components were mapped in a perpendicular section, 50% in of an occlusive clot. The trained files for each cellular components were uploaded to the Arivis Pro software, and were applied to the whole blended image using deep learning algorithm through a pipeline. Green, area of tightly packed platelets; blue, elongated platelets; red, RBCs; yellow, WBCs. The upper bar represents the FeCl3 application site. In panel B, the cellular components were mapped in a parallel section, 50% of an occlusive clot in Arivis Pro software using the same algorithm.

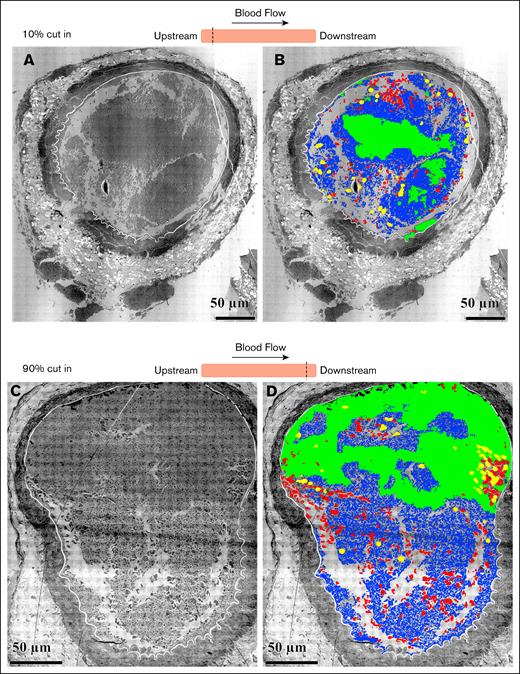

To investigate quantitatively the structural organization and distribution of the participating cells in a clot, we used software to analyze cell type distributions (elongated platelets, tightly packed platelets, RBCs, and WBCs) at various clot depths. In cross-section, occlusive clots were ∼230 mm in diameter, approximately the same diameter as a femoral puncture wound. Quantitatively, the clots consisted primarily of platelets, some RBCs, and rare WBCs (Table 2). Platelets were further divided into areas of tightly packed (little space between platelets) and elongated platelets, often appearing discoid. In addition, empty holes and intracellular spaces occupy the clot. A few black bodies were also scored. About half of a clot was filled with the elongated, loosely packed platelets, and associated intracellular spaces (Table 2). Tightly packed platelets were the second most common component at 40% to 50%. About 5% of the area was occupied by entrapped RBCs. In total, 90% to 95% of the central portion of the clot was occupied by platelets and associated inter-platelet spacing. A small number of WBCs (yellow) were trapped inside the mid-clot cross-section. On the upstream and downstream ends of the clot (Figure 6), we observed numerous RBCs and WBCs. Overall, the distribution of cell types suggests that WBC accumulation becomes enhanced as the clot grows out from the central region of initial formation and platelet accumulation becomes less. We infer that platelet adherence “squeezes” out other cell types. We suggest that the data are more consistent with the vaulted structures on which the puncture wound cap-and-build model5 is based than the mounded, 2-zoned structure as summarized in a core-and-shell model.12

Enumeration of components of a clot: stable clots were fixed 20 minutes after FeCl3 treatment (C57BL/6 wild-type mice)

| Clot traits . | Perpendicular to flow (cross-section, 1) . | Parallel (longitudinal, 2) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occlusion . | Upstream end . | Downstream end . | Occlusion . | |||||

| 50% in . | 10% in . | 90% in . | Middle 800 mm length . | |||||

| Area, μm2 . | % . | Area, μm2 . | % . | Area, μm2 . | % . | Area, μm2 . | % . | |

| Densely packed platelets | 30 165 | 39 | 10 927 | 24 | 21 086 | 38 | 114 450 | 53 |

| Loosely packed platelets | 12 869 | 17 | 20 889 | 45 | 17 556 | 31 | 37 756 | 18 |

| Void volume between platelets: loosely packed platelet spacing between platelets, 100 to 200 nm | 26 435 | 34 | 3088 | 7 | 4900 | 8 | 55 092 | 26 |

| RBCs | 4113 | 5 | 1966 | 4 | 3511 | 6 | 6028 | 3 |

| WBCs | 225 | 0.5 | 1061 | 2 | 1276 | 2 | 1006 | 0.5 |

| Cell-free void area | 3491 | 4 | 8113 | 18 | 8572 | 15 | 1926 | 1 |

| Black bodies | 93 | 0.1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total area | 77 391 | 100 | 46 044 | 100 | 56 759 | 100 | 216 258 | 100 |

| Clot traits . | Perpendicular to flow (cross-section, 1) . | Parallel (longitudinal, 2) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occlusion . | Upstream end . | Downstream end . | Occlusion . | |||||

| 50% in . | 10% in . | 90% in . | Middle 800 mm length . | |||||

| Area, μm2 . | % . | Area, μm2 . | % . | Area, μm2 . | % . | Area, μm2 . | % . | |

| Densely packed platelets | 30 165 | 39 | 10 927 | 24 | 21 086 | 38 | 114 450 | 53 |

| Loosely packed platelets | 12 869 | 17 | 20 889 | 45 | 17 556 | 31 | 37 756 | 18 |

| Void volume between platelets: loosely packed platelet spacing between platelets, 100 to 200 nm | 26 435 | 34 | 3088 | 7 | 4900 | 8 | 55 092 | 26 |

| RBCs | 4113 | 5 | 1966 | 4 | 3511 | 6 | 6028 | 3 |

| WBCs | 225 | 0.5 | 1061 | 2 | 1276 | 2 | 1006 | 0.5 |

| Cell-free void area | 3491 | 4 | 8113 | 18 | 8572 | 15 | 1926 | 1 |

| Black bodies | 93 | 0.1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total area | 77 391 | 100 | 46 044 | 100 | 56 759 | 100 | 216 258 | 100 |

Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution clot components in perpendicular sections at upper and lower ends within an occlusive clot. The samples are cross-sections cut perpendicular to the blood flow of an occluded femoral artery fixed 20 minutes after FeCl3 application. (A) Upstream end of the clot, 10% in cut. (B) Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution of clot components at the upper end. Green, area of tightly packed platelets; blue, elongated platelets; red, RBCs; yellow, WBCs. (C) Downstream end of the clot, 90% in cut. (D) Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution of clot components at the lower end. Green, area of tightly packed platelets; blue, elongated platelets; red, RBCs; yellow, WBCs.

Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution clot components in perpendicular sections at upper and lower ends within an occlusive clot. The samples are cross-sections cut perpendicular to the blood flow of an occluded femoral artery fixed 20 minutes after FeCl3 application. (A) Upstream end of the clot, 10% in cut. (B) Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution of clot components at the upper end. Green, area of tightly packed platelets; blue, elongated platelets; red, RBCs; yellow, WBCs. (C) Downstream end of the clot, 90% in cut. (D) Cloud-based AI analysis of the distribution of clot components at the lower end. Green, area of tightly packed platelets; blue, elongated platelets; red, RBCs; yellow, WBCs.

Syk inhibitor sensitivity and its structural consequences

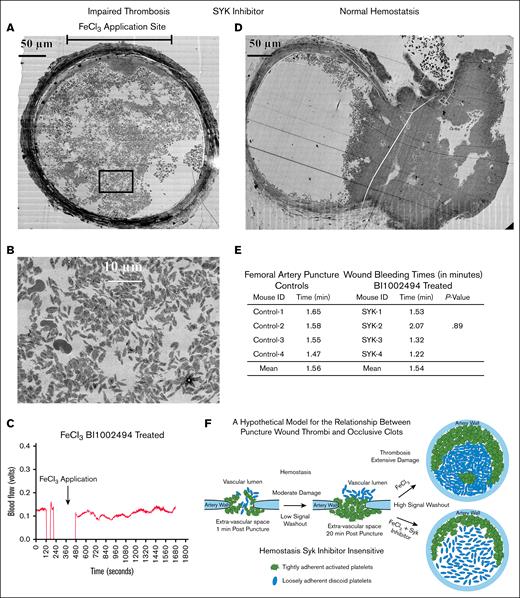

As a final test set, we probed the structure of any clot residue that might form in the presence of Syk inhibitor, our validator of physiological signaling.17,23 By video microscopy, all 4 of the BI 1002494 samples examined in detail showed a faint white intra-arterial haze rather than the distinct clot seen in non–drug-treated FeCl3-induced mice, suggesting that structure must be formed. As shown in Figure 7A, the vessel wall in the BI 1002494–treated mice showed wall darkening suggestive of the expected FeCl3-induced wall damage, and a loss of corrugation along the inner surface of the vessel wall; traits normally associated with occlusion. However, WA-TEM revealed a very porous clot in which the formation of a tightly adherent zone of platelets extending around about one-third of the vessel rim was obvious (Figure 7A). At its thickest, this rim extended almost 50 μm into the interior of the femoral artery. However, instead of a coherent, platelet-rich, pocketed, interior infill of the artery, the WA-TEM showed a highly porous, dispersed pattern of small platelet clumps with many platelets very loosely aggregated (Figure 7A-B). Strikingly, most of the platelets concentrated in the vessel interior were discoid in shape, and showed only a low incidence of α-granule secretion. Considering that there was structure, one might expect some effect on blood flow. However, as shown in Figure 7C, blood flow was normal for the entire post-FeCl3 treatment monitoring period, and in the other 3 detailed cases studied. In conclusion, these results suggest that BI 1002494 within arteries acts by selectively stalling the platelet activation cascade at the conversion of platelets from a discoid shape to a more rounded, more adherent, pseudopod extending state.15 This is a surprising outcome as no inhibition was seen in a femoral artery puncture wound model (Figure 7D-E, control [no drug]; supplemental Figure 9), even though the size of the puncture hole and the diameter of the arterial lumen were similar. For a summary of thrombus properties, see Table 3.

Clot formation in Syk-treated FeCl3 and punctured wound murine model. (A) Perpendicular section approximately middle of a Syk + FeCl3-treated nonocclusive thrombus/sample. (B) A zoomed area from FeCl3-treated nonocclusive thrombus shows a dispersed distribution of elongated platelets leaving large pores in between. (C) Blood flow was monitored and measured with a transit-time perivascular flowmeter and sonic probe. Arrows indicate the timing of FeCl3 treatment. The initial segment was the flow signal detected before FeCl3 treatment. The flow probe signal dropped out as fluid in the vessel’s surroundings was removed to prevent FeCl3 dilution. Fluid was reintroduced upon removal of FeCl3 filter paper, and the flow probe again became functional. Following FeCl3 application, ∼20 minutes of probe flow signal data were collected. No dip in flow signal following treatment indicates no occlusion. (D) Perpendicular section of a Syk-treated punctured model shows a normal clot formation with outer vault consisting of highly activated and tightly packed platelets, while inner crowning consists of elongated, mostly discoid, and loosely packed platelets. (E) The table shows comparison of bleeding time in punctured wound femoral artery model between controls and Syk (BI 1002494)–treated mice. The P value is from a Student t test comparison of the mean bleeding times for control and BI 1002494–treated samples. (F) Cartoon model of proposed relationship between femoral puncture thrombus and an occlusive clot.

Clot formation in Syk-treated FeCl3 and punctured wound murine model. (A) Perpendicular section approximately middle of a Syk + FeCl3-treated nonocclusive thrombus/sample. (B) A zoomed area from FeCl3-treated nonocclusive thrombus shows a dispersed distribution of elongated platelets leaving large pores in between. (C) Blood flow was monitored and measured with a transit-time perivascular flowmeter and sonic probe. Arrows indicate the timing of FeCl3 treatment. The initial segment was the flow signal detected before FeCl3 treatment. The flow probe signal dropped out as fluid in the vessel’s surroundings was removed to prevent FeCl3 dilution. Fluid was reintroduced upon removal of FeCl3 filter paper, and the flow probe again became functional. Following FeCl3 application, ∼20 minutes of probe flow signal data were collected. No dip in flow signal following treatment indicates no occlusion. (D) Perpendicular section of a Syk-treated punctured model shows a normal clot formation with outer vault consisting of highly activated and tightly packed platelets, while inner crowning consists of elongated, mostly discoid, and loosely packed platelets. (E) The table shows comparison of bleeding time in punctured wound femoral artery model between controls and Syk (BI 1002494)–treated mice. The P value is from a Student t test comparison of the mean bleeding times for control and BI 1002494–treated samples. (F) Cartoon model of proposed relationship between femoral puncture thrombus and an occlusive clot.

Summary of clot properties

| Mouse . | Sectioning . | Clot traits . | Infill . | Analysis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perpendicular, 50% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Elongated and loosely packed platelets, large area of tightly packed platelets, several RBCs, and very few WBCs | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 1 | Perpendicular, 10% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Elongated and loosely packed platelets, smaller area of tightly packed platelets, plenty RBCs and WBCs, and larger area of empty space | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 1 | Perpendicular, 90% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Collapsed vessel wall, elongated and loosely packed platelets, smaller area of tightly packed platelets, plenty RBCs and WBCs, and larger area of empty space | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 2 | Longitudinal, 50% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Elongated, rounded, and loosely packed platelets, large area of tightly packed platelets, RBCs, and WBCs | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 3 | Perpendicular, 50% cut in | Deionized water–treated nonocclusive clot | Empty lumen contains plenty RBCs | Qualitative |

| 4 | Perpendicular, 50% cut in | FeCl3 + Syk inhibitor–treated impaired occlusive clot | Elongated, rounded, and dispersed platelets, small area of tightly packed platelets, and RBCs | Qualitative |

| 5 | Perpendicular | Syk-treated puncture wound clot | Outer vault of tightly packed platelets, luminal elongated, and loosely packed platelets, and RBCs | Qualitative |

| 6 | Perpendicular | Control puncture wound clot | Outer vault of tightly packed platelets, luminal elongated, and loosely packed platelets, and RBCs | Qualitative |

| Mouse . | Sectioning . | Clot traits . | Infill . | Analysis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perpendicular, 50% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Elongated and loosely packed platelets, large area of tightly packed platelets, several RBCs, and very few WBCs | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 1 | Perpendicular, 10% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Elongated and loosely packed platelets, smaller area of tightly packed platelets, plenty RBCs and WBCs, and larger area of empty space | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 1 | Perpendicular, 90% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Collapsed vessel wall, elongated and loosely packed platelets, smaller area of tightly packed platelets, plenty RBCs and WBCs, and larger area of empty space | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 2 | Longitudinal, 50% cut in | FeCl3-treated occlusive clot | Elongated, rounded, and loosely packed platelets, large area of tightly packed platelets, RBCs, and WBCs | Cloud-based AI mapping |

| 3 | Perpendicular, 50% cut in | Deionized water–treated nonocclusive clot | Empty lumen contains plenty RBCs | Qualitative |

| 4 | Perpendicular, 50% cut in | FeCl3 + Syk inhibitor–treated impaired occlusive clot | Elongated, rounded, and dispersed platelets, small area of tightly packed platelets, and RBCs | Qualitative |

| 5 | Perpendicular | Syk-treated puncture wound clot | Outer vault of tightly packed platelets, luminal elongated, and loosely packed platelets, and RBCs | Qualitative |

| 6 | Perpendicular | Control puncture wound clot | Outer vault of tightly packed platelets, luminal elongated, and loosely packed platelets, and RBCs | Qualitative |

A total of 8 samples were imaged by WA-TEM, ∼800 frames per montaged WA-TEM, 4K by 4K image capture, ∼6400 total image frames.

AI, artificial intelligence.

Discussion

Despite rapid progress in characterizing signaling pathways in hemostasis and thrombosis, our understanding of the internal structure of occlusive clots is limited. Past analysis relied on small, easily exposed arterioles, which lend themselves to live-animal, light microscopy.29 While these methods give near continuous readouts for kinetic assessments, they lack spatial resolution, and failed to effectively report on the interior of a forming clot.3,4,12,29 In contrast, WA-TEM yields high-resolution images of individual platelets over the entire clot, both surface and interior.15,23 Though continuous imaging is not possible, time point analysis is. To define better the extent to which occlusion is an extension of structural principles embodied in current models, we used WA-TEM to characterize individual platelet properties in FeCl3-induced thrombi in a murine femoral artery model. We defined adherence patterning of platelets at the clot-vessel wall interface and within the clot’s interior, as well as granule state. Using this approach and an inhibitor that affects platelet signaling (BI 1002494, a Syk inhibitor16,17), we report 4 major outcomes that inform on the structural properties of occlusive clotting, and from which inferences regarding clot formation processes in the femoral artery can be made. Based on these outcomes, we suggest an explanatory model for arterial thrombosis (Figure 7F).

First, topically applied FeCl3 induced an occlusive clot in the femoral artery in which the vessel wall was marked by “iron-blackened” smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, and disrupted endothelial cells. Distal to the wall, we scored hundreds of thousands of individual platelets, whose morphology appeared to be morphologically consistent with that seen in thrombi formed in puncture wounds.15,23 Entrapped polyhedral RBCs were also similar in morphology to those found in the hemostatic puncture wound clot. Consistent with expected platelet physiology, pretreatment with a Syk inhibitor that blocks signaling from ITAM receptors (eg, GPVI) blocked occlusion, supporting the conclusion that our experimental system reports on physiological signaling.

Second, highly activated platelets, which were devoid of major organelles (ie, α-granules and mitochondria), were restricted to a zone ∼5 μm from the FeCl3-damaged endothelial cell layer and entrapped polyhedral RBCs. This suggests that the zone of highest agonist concentration likely only extends luminally for a small fraction of the ∼230-μm diameter femoral artery.

Third, tightly adherent, rounded platelets, and more loosely adherent, more discoid shaped platelets were the major constituents of occlusive clots, and displayed a distinct partitioning. Tightly adherent, α-granule–positive platelets formed a distinct zone extending outward by 25 to 75 μm from the highly activated rim of damaged endothelial layer platelets that anchored the clot to the damaged vessel wall. Columns of tightly adherent platelets extended into the interior of the vessel, leaving spaces in between that we term pockets, which were filled with loosely adherent, more discoid shaped platelets and occasional clusters of what appeared to be entrapped, polyhedral RBCs. Based on platelet morphology and the presence of α-granules, these data indicate a relatively low, nonhomogeneous signaling intensity (perhaps due to agonist concertation) within the interior of the FeCl3-induced clot. Based on the core-and-shell model of thrombosis, one might have expected a rim of highly activated platelets with tightly adherent ones forming a progressive gradient to more loosely adherent platelets within the central portion of the clot extending into the vessel lumen. Such a progressive gradient was not observed; thus, our data fail to confirm the predictions of a core-and-shell model.

Fourth, blocking Syk activity inhibited occlusion as denoted by full blood flow, but unexpectedly a uniquely structured thrombus was formed. The thrombus was adherent to the vessel wall, and its interior contained very loosely adherent, mostly discoid shaped platelets that were anchored to a rim of tightly adherent platelets attached to the damaged endothelial layer. This suggests that initial adherence to the vessel wall does not require Syk-based signaling, but that thrombus growth and further platelet adhesion does.

In conclusion, we draw attention to both the exhibited commonalities and differences in platelet response to drug in the puncture wound clot vs the FeCl3-induced clot, that is, hemostasis vs thrombosis. The Syk inhibitor BI 100249416,17 had no effect on femoral artery puncture wound bleeding time or on the structure of the resulting wound thrombus. Yet thrombosis, that is, loss of blood vessel patency, was prevented with drug treatment. The selective effect found here on bleeding time vs occlusion, hemostasis vs thrombosis, is consistent with previous literature.17 What is novel in our report is the ability of structural analysis to point to a local stratification in platelet response. In both cases, Syk inhibition had no effect on damage site proximal platelet aggregation into tightly adherent thrombi anchored to the immediate damage site. What was affected was platelet aggregation within the interior of the artery. In the puncture wound case aggregation was limited; thrombus growth stopped, the normal outcome. However, in the Syk-treated FeCl3 induction case, aggregation continued to produce a loosely adherent platelet aggregate rich in discoid platelets that had no effect on blood flow. In brief, what was prevented was the expected further activation of the platelets, the generation of tightly adherent platelet aggregates, and subsequent platelet infill, a set of outcomes consistent with a differential effect on integrin activation.19

How can these outcomes be explained? Rheological properties of arterial blood flow could explain this difference.30 Conceivably, gavage-administered BI 1002494 concentration may be higher in the interior of the artery than the periphery where flow is a weaker mixing force. Another possibility is that local signaling in the arterial periphery, but not the interior, is of sufficient intensity to offset the effects of the inhibitor. Both explanations point to an important threshold in platelet activation. Whether these structural ramifications carry over to humans is an open question. We note that the effectiveness of the Syk inhibitor on ITAM receptor signaling in human platelets could differ from that of mice. Mice have 2 ITAM receptors, with GPVI being the more important,20,21 while humans have 3 receptors.19 To our knowledge, these experimental outcomes are the first reported case of a platelet activation state-specific response to a drug family,31 Syk inhibitors. Our data could be an indicator of stage specificity as a new target for modulating platelet outcomes.

Acknowledgments

BI 1002494 was provided at no charge to the investigators by the opnMe program of Boehringer Ingelheim.

The authors gratefully acknowledge grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL119393, R56 HL119393, and R01 HL155519 [B.S.]). The authors thank Sidney W. Whiteheart, University of Kentucky, for comments and suggestions on “Discussion.”

Authorship

Contribution: I.D.P. and K.K.B. produced the data; S.W.R. planned and implemented initial clotting experiments; M.W.W. performed the platelet spacing analysis; M.O.F. analyzed data, produced tables and graphs, and wrote the first version of the manuscript; B.S. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, tables and graphs, and the supplemental material; and all authors contributed to the conception, design, and interpretation of the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brian Storrie, Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham St, Little Rock, AR 72205; email: storriebrian@uams.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented in abstract form at the 63rd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 9 to 12 December 2023.

Image sets are available on request from the corresponding author, Brian Storrie (storriebrian@uams.edu), and have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Public Image Archive, an image-sharing site sponsored by the European Bioinformatics Institute.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.